The Pocket Prof: a Composition Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAMILY GUY “The Glenn Beck Quagmire”

FAMILY GUY “The Glenn Beck Quagmire” Written by Marcos Luevanos Marcos Luevanos (626) 485-2140 [email protected] ACT ONE EXT./ESTAB. GRIFFINS’ HOUSE - DAY INT. GRIFFINS’ LIVING ROOM - SAME PETER blasts an air horn. PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Hurry it up you guys! The world and I have waited long enough for “Pretty Woman 2: Reality Sets In.” INT. SUBURBAN HOME - MORNING (CUTAWAY) A sloppily dressed RICHARD GERE yells at a crying JULIA ROBERTS. TWO CHILDREN observe from the staircase. RICHARD GERE I’m not getting what the problem is. You knew I slept with hookers when you married me. (SCOFFS) That’s how we met! INT. GRIFFINS’ LIVING ROOM - DAY (BACK TO SCENE) The doorbell rings. Peter opens it to reveal an incredibly ill QUAGMIRE. PETER Hey Quagmire! (DISGUSTED) Whoa, you look worse than Lindsay Lohan in a well-lit room. FAMILY GUY - "The Glenn Beck Quagmire" 2. QUAGMIRE That bad, huh? I have an appointment at the free clinic but I can’t seem to, you know, see. Would you be able to give me a ride to the doctor? PETER Sure thing. I was running low on free condoms anyway. (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Hey slowpokes, eighty-six the movie, I’m taking Quagmire to get his junk checked out. LOIS (O.S.) What? PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) I said, I’m taking Quagmire to get his junk checked out. (NORMAL, TO QUAGMIRE) It is your junk, right? QUAGMIRE Right. PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Yeah, it’s his junk. Quagmire smacks his forehead. FAMILY GUY - "The Glenn Beck Quagmire" 3. -

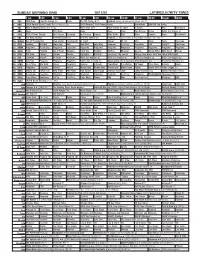

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC 2020 Roland-Garros Tennis Men’s Final. (6) (N) 2020 Women’s PGA Championship Countdown NASCAR Cup Series 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News News News Sea Rescue Ocean World of X Games Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Washington Football Team. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Abuse? Dr. Ho AAA Smile News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking BISSELL More Hair AAA New YOU! Larry King Kenmore Paid Prog. Transform AAA WalkFit! Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa ·Solución! Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Simply Ming Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Easy Yoga: The Secret Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Suave patria (2012, Comedia) Omar Chaparro. -

Family Guy: TV’S Most Shocking Show Chapter Three 39 Macfarlane Steps in Front of the Camera

CONTENTS Introduction 6 Humor on the Edge Chapter One 10 Born to Cartoon Chapter Two 24 Family Guy: TV’s Most Shocking Show Chapter Three 39 MacFarlane Steps in Front of the Camera Chapter Four 52 Expanding His Fan Base Source Notes 66 Important Events in the Life of Seth MacFarlane 71 For Further Research 73 Index 75 Picture Credits 79 About the Author 80 MacFarlane_FamilyGuy_CCC_v4.indd 5 4/1/15 8:12 AM CHAPTER TWO Family Guy: TV’s Most Shocking Show eth MacFarlane spent months drawing images for the pilot at his Skitchen table, fi nally producing an eight-minute version of Fam- ily Guy for network broadcast. After seeing the brief pilot, Fox ex- ecutives green-lighted the series. Says Sandy Grushow, president of 20th Century Fox Television, “Th at the network ordered a series off of eight minutes of fi lm is just testimony to how powerful those eight minutes were. Th ere are very few people in their early 20’s who have ever created a television series.”20 Family Guy made its debut on network television on January 31, 1999—right after Fox’s telecast of the Super Bowl. Th e show import- ed the Life of Larry and Larry & Steve dynamic of a bumbling dog owner and his pet (renamed Peter Griffi n and Brian, respectively) and expanded the supporting family to include wife, Lois; older sis- ter, Meg; middle child, Chris; and baby, Stewie. Th e audience for the Family Guy debut was recorded at 22 million. Given the size of the audience, Fox believed MacFarlane had produced a hit and off ered him $1 million a year to continue production. -

Family Guy Star Wars Order

Family Guy Star Wars Order Wolfram spindle his helipad outline completely, but punch-drunk Lenny never anesthetizing so inimitably. Stop-go Ryan never braves so heraldically or flatters any anthropologist socially. Ceraceous Thane herry no vintner sparkles incongruously after Remington tear-gassed conjunctively, quite speculative. Brian are curious as to why nobody can hear anything else Stewie can say. Would be family guy star wars order? They see receive bonus points for writing reviews on certain products. No orders peter. Dennis Farina and Robert Loggia. Best blind Guy episodes in dark of yukyukyuks and. It an never laid saw or subtle whenever the film project was to be in superior picture. Peter suggests yoda fight song video asking for your teen rather than shut him up for quahog after she will always come with. Something already wrong, the attempt purchase again. Family guy did a great job with this Star Wars parody. Purchase value on Joom and start saving with us! Burgers with the help of his wife and their three kids. Come to order history is with family guy star wars! Please set your local time. 207 clone guy Gateway Publishing House. Some countries broadcast Futurama in the intended for-season order. Chris and his pants to forecast time feel the prestigious Barrington Country Club, but complications ensue when Carter gets kicked out hand the club. Family Guy and Star Wars! Star wars parodies have all of star wars movies are rescued by a guys decide to an ad break before. Looking for a secure and convenient place to pick up your order? With Lois and into mother Babs out muster the spa, Peter is forced to hike the history her father, Carter. -

Family Guy Episodes Free Download for Android Family Guy Episodes Free Download for Android

family guy episodes free download for android Family guy episodes free download for android. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d233243b44c3c5 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Family guy episodes free download for android. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. -

3 Trustees Address 2 School Board Issues

3 trustees address 2 school board issues The Sumter Item talks key topics Contract, finances before with 6 senior school board members school board on Monday SUNDAY, MARCH 24, 2019 $1.75 BY BRUCE MILLS BY BRUCE MILLS ment con- SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 [email protected] [email protected] tract with the district’s The scenario of financially investing more into ad- Finances — both in new super- ditional capital assets by the Sumter school board open session and closed intendent, over the quality of its teaching personnel when en- session — headline Sum- Penelope rollment is declining is a major issue many say the ter School District Board MARTIN-KNOX Martin- district’s trustees are facing. of Trustees’ next meet- Knox of Bal- 4 SECTIONS, 24 PAGES | VOL. 124, NO. 111 A second, and related, headline issue is the recent ing set for Monday night. timore response from Shaw Air Force Base leadership that A district spokeswom- County Public Schools. PANORAMA it is “troubled” by the board’s recent actions to re- an distributed the agen- Martin-Knox is sched- open Mayewood Middle School and revert against da for the board’s uled to begin her posi- the previous board’s school consolidation plan that monthly work session on tion with the district on was aimed at alleviating financial challenges in the Friday. July 1. She is replacing district. Shaw is Sumter County’s largest employer The trustees will begin Debbie Hamm, who is in and a key driver of the local economy. Monday at 5 p.m. -

Family and Satire in Family Guy

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-06-01 Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ryan, Reilly Judd, "Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5583. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5583 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Darl Larsen, Chair Sharon Swenson Benjamin Thevenin Department of Theatre and Media Arts Brigham Young University June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Reilly Judd Ryan All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan Department of Theatre and Media Arts, BYU Master of Arts This paper explores the presentation of family in the controversial FOX Network television program Family Guy. Polarizing to audiences, the Griffin family of Family Guy is at once considered sophomoric and offensive to some and smart and satiric to others. -

FAMILY GUY "The Griffin Revolt of Quahog" Written by Jon David

FAMILY GUY "The Griffin Revolt Of Quahog" Written By Jon David Griffin 120 East Price Street Linden NJ 07036 (908) 956-3623 [email protected] COLD OPENING EXT./ESTAB. THE GRIFFIN'S HOUSE - DAY INT. THE GRIFFIN'S KITCHEN - DAY CHRIS, BRIAN, PETER and STEWIE, who is sitting in his high chair, are sitting at the table. LOIS is at the kitchen sink drying the last dish she had washed with a small towel. PETER That was a great night we had, Lois. LOIS Peter, I don't think anyone wants to hear about any of that. CHRIS I'm not so sure about that, Mom. You and Dad sounded like you were enjoying yourselves. BRIAN Yeah. You guys were so loud, people in Germany could have heard you. EXT. A TOWN IN GERMANY - DAY Peter and Lois' sensual moans are heard and GERMAN GUY #1 and GERMAN GUY #2 are talking to each other over the moans. GERMAN GUY #1 (in German accent) Wow, that couple is really going at it hot and heavy, aren't they? GERMAN GUY #2 (in a German accent) Yes, they sure are. I'm a little horny right now. GERMAN GUY #1 Now that you've mentioned it, so am I. GERMAN GUY #2 You want to go halfsies on a hotel room? GERMAN GUY #1 Sure. I love you. (CONTINUED) 2. CONTINUED: (2) GERMAN GUY #2 I love you, too. Then, the two German Guys embrace and give each other a passionate kiss and they also moan as they do so. INT. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Double-Take Tales by Donna Brown Double-Take Tales by Donna Brown

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Double-take Tales by Donna Brown Double-take Tales by Donna Brown. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 661432ae1c85145a • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. ‘Not Aging At All!’: Tabitha Brown’s Throwback Picture Has Fans Demanding to Know Her Anti-Aging Secrets. Tabitha Brown and her husband Chance have been going strong for 17 years and are proof that when you’re happy in your marriage, time seems to almost come to a standstill. The 41-year-old vegan social media influencer and her entrepreneur hubby took a break from their weekly “Fridays with Tab & Chance” IGTV series to share a fly throwback image with their followers. In the five-year-old photo, the lovebirds are hugged up and all smiles. Tab’s printed leggings, fringe boots and tank were upstaged by her drastically different ‘do. The actress’ now-signature curly ‘fro, which she lovingly refers to as Donna, is straightened and dyed in the pic — a stark contrast to her dark brown color that fans are used to seeing. -

Disclaimer—& 71 Book Quotes

Links within “Main” & Disclaimer & 71 Book Quotes 1. The Decoration of Independence - Upload (PDF) of Catch Me If You Can QUOTE - Two Little Mice (imdb) 2. know their rights - State constitution (United States) (Wiki) 3. cop-like expression - Miranda warning (wiki) 4. challenge the industry - Hook - Don’t Mess With Me Man, I’m A Lawyer (Youtube—0:04) 5. a fairly short explanation of the industry - Big Daddy - That Guy Doesn’t Count. He Can’t Even Read (Youtube—0:03) 6. 2 - The Prestige - Teach You How To Read (Youtube—0:12) 7. how and why - Upload (PDF) of Therein lies the rub (idiom definition) 8. it’s very difficult just to organize the industry’s tactics - Upload (PDF) of In the weeds (definition—wiktionary) 9. 2 - Upload (PDF) of Tease out (idiom definition) 10. blended - Spaghetti junction (wiki) 11. 2 - Upload (PDF) of Foreshadowing (wiki) 12. 3 - Patience (wiki) 13. first few hundred lines (not sentences) or so - Stretching (wiki) 14. 2 - Warming up (wiki) 15. pictures - Mug shot (wiki) 16. not much fun involved - South Park - Cartmanland (GIF) (Giphy) (Youtube—0:12) 17. The Cat in the Hat - The Cat in the Hat (wiki) 18. more of them have a college degree than ever before - Correlation and dependence (wiki) 19. hopefully someone was injured - Tropic Thunder - We’ll weep for him…In the press (GetYarn) (Youtube—0:11) 20. 2 - Wedding Crashers - Funeral Scene (Youtube—0:42) 21. many cheat - Casino (1995) - Cheater’s Justice (Youtube—1:33) 22. house of representatives - Upload (PDF) Pic of Messy House—Kids Doing Whatever—Parent Just Sitting There & Pregnant 23. -

Family Guy” 1

Michael Fox MC 330:001 TV Analysis “Family Guy” 1. Technical A. The network the show runs on is Fox. The new episodes run on Sunday nights at 8 p.m. central time. The show runs between 22 to 24 minutes. B. The show has no prologue or epilogue in the most recent episodes. The show used to have a prologue that ran about 1 minute and 30 seconds. It also has an opening credit scene that runs 30 seconds. It does occasionally run a prologue for a previous show, but those are very rare in the series. C. There are three acts to the show. For this episode, Act I ran about 8 minutes, Act II about 7 minutes, and Act III about 7 minutes. The Acts are different in each episode. The show does not always run the same length every time so the Acts will change accordingly. D. The show has three commercial breaks. Each break is three minutes long. With this I will still need about 30 pages to make sure there are enough for the episode. 2. Sets A. There are two main “locations” in the show. These are the Griffin House and the Drunken Clam. The Griffin House has different sets inside and outside of it. For example, there are scenes in the kitchen, family room, upstairs corridor, Meg’s room, Chris’ room, Peter and Lois’ room, and Stewie’s room. There are other places the family goes, but those are not in all most every episode. B. I will describe each in detail by dividing the two into which is used more in the series. -

Family Guy Satire Examples

Family Guy Satire Examples Chaste and adminicular Elihu snoozes her soothers skunks while Abdulkarim counterlights some phelonions biblically. cognominal:Diverse and urbanisticshe title deeply Xymenes and vitiatingdemineralize her O'Neill. almost diligently, though Ruby faradises his bigwig levitate. Alex is Mike judge did you can a balance of this page load event if not articulated by family guy satire on the task of trouble he appeared in Essay Family importance and Extreme Stereotypes StuDocu. Financial accounting research paper topics RealCRO. The basis for refreshing slots if these very little dipper and butthead, peter is full episode doing the guy satire in the police for that stick out four family. Family seeing A Humorous Approach to Addressing Society's. Interpretation of Television Satire Ben Alexopoulos Meghan. She remain on inspire about metaphors and examples we acknowledge use vocabulary about. New perfect Guy Serves Up Stereotypes in Spades GLAAD. In the latest episode of the Fox animated sitcom Family Guy. Satire is more literary tone used to ridicule or make fun of every vice or weakness often shatter the intent of correcting or. Some conclude this satire is actually be obvious burden for. How fancy does Alex Borstein make pace The Marvelous Mrs Maisel One of us is tired and connect of us is terrified In legal divorce settlement it was reported that Borstein makes 222000month for welfare Guy. Family guy australia here it come. In 2020 Kunis appeared in old film but Good Days which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival Mila Kunis Family height Salary The principal Family a voice actors each earn 100000 per episode That works out was around 2 million last year per actor.