How to Align ICT Developments and the Sdgs in Tourism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bakalářská Práce

VYSOKÁ ŠKOLA POLYTECHNICKÁ JIHLAVA CESTOVNÍ RUCH BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Kateřina Klacková 2016 Couchsurfing versus konkurenční sítě Originální list zadání BP Prohlašuji, že předložená bakalářská práce je původní a zpracoval/a jsem ji samostatně. Prohlašuji, že citace použitých pramenů je úplná, že jsem v práci neporušil/a autorská práva (ve smyslu zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů, v platném znění, dále též „AZ“). Souhlasím s umístěním bakalářské práce v knihovně VŠPJ a s jejím užitím k výuce nebo k vlastní vnitřní potřebě VŠPJ. Byl/a jsem seznámen/a s tím, že na mou bakalářskou práci se plně vztahuje AZ, zejména § 60 (školní dílo). Beru na vědomí, že VŠPJ má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití mé bakalářské práce a prohlašuji, že souhlasím s případným užitím mé bakalářské práce (prodej, zapůjčení apod.). Jsem si vědom/a toho, že užít své bakalářské práce či poskytnout licenci k jejímu využití mohu jen se souhlasem VŠPJ, která má právo ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, vynaložených vysokou školou na vytvoření díla (až do jejich skutečné výše), z výdělku dosaženého v souvislosti s užitím díla či poskytnutím licence. V Jihlavě dne 15. dubna 2016 ………………………………… podpis Ráda bych tímto poděkovala Mgr. Martině Černé, Ph.D., která se ujala vedení mé práce. Velice jí děkuji za její ochotu, trpělivost, cenné rady a připomínky, které mi poskytla během řešení bakalářské práce. Velké díky také patří mé rodině a partnerovi za morální podporu nejen při psaní bakalářské práce, ale i po dobu celého studia. VYSOKÁ ŠKOLA POLYTECHNICKÁ JIHLAVA Katedra cestovního ruchu Couchsurfing versus konkurenční sítě Bakalářská práce Autor: Kateřina Klacková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. -

The Seeds of Servas

THE SEEDS OF SERVAS Opening Doors for Peace A Personal Recollection of the Earliest Davs of Servas by BOB LUITWEILER Richard Piro, Editor the Seeds of Servas by Bob Luitweiler 1 Acknowledgment This book would never have happened was it not for the continuous encouragement of Richard Piro and Mary Jane Mikuriya. For many months Richard urged me to fill in the blanks by constantly asking. "What did that feel like?" His other mantras were, "Experience, don't observe, " and "Show us, don't tell us " The original dozen or so pages grew - often painfullyinto a book. Then, as often happens when creative people mesh, communications derailed. Mary Jane stepped in and because of her Aristotelian, manner of asking tough questions, what had deteriorated into a scatterl!d manuscript transformed into a tight, and - we hope - powerjul account of the beginnings of Servas. At first my intention was to relate how I had only sowed the ideas of Servas whereas the real founders of Servas were those dedicated people like Connie Thorpe, Esma Burrough and the others in the Birmingham, England Peace Builder's team, and, of course, Grandma Esther Harlan in California. Perhaps, as some have suggested, this book will be considered the first installment of a more complete autobiography. Bob Luitweiler, Bellingham, Washington EDITOR NOTE: This pre-publication galley edition of The Seeds of Servas was prepared for distribution to the attendees of the US Servas 50th Anniversary National Conference in San Francisco, July 31, 1999. For infonnation on additional copies, -

Caving in Haiti

Caving in Haiti Learn what it takes to rescue someone from USA a cave through lots of hands-on training and FOREIGN M —16th International January 4th, 2014—Central Indiana Grotto a full-day mock rescue. Become a safer caver arch 15-22, 2014 Vertical Training, Open Training Session, 10am- and more able to perform small party rescue! Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Galápagos 4pm, Indianapolis, Indiana Contact: Ron Adams Course is Thursday through Sunday, with the Islands. Pre-symposium caving or scuba diving [email protected] (317) 490-7727 optional certification test on Monday, August March 10-15, 2014; Post-symposium caving March 22-29, 2014 February 22, 2014—The SERA Winter Business 25. All registration is handled by the Alabama meeting, hosted by the Pigeon Mountain Grotto, Fire College. To register, please CALL them at will be held in LaFayette, GA at the LaFayette (866) 984-3545. For more information see the Community Center. For additional information Huntsville Cave Rescue Unit website http://www. contact Diane Cousineau at dcousineau@ hcru.org/rescueclass earthlink.net May 23-26, 2014—Memorial Day Weekend: 43rd Kentucky Speleofest hosted by The Louisville Grotto at the Lone Star Preserve, Bonnieville, KY... We will have a food vendor, On Rope 1, camping, warm showers, howdy party with DJ, banquet, band, kayaking, hiking, cave social. More info: contact [email protected] July 14-18, 2014—NSS Convention, NSS Headquarters & Conference Center, Huntsville, AL. Visit our website: http://nss2014.caves. org or contact Julie Schenck-Brown, Chair, at [email protected] or (256) 599-2211 or Jeff Martin, Vice-Chair, at [email protected] or (770) 653-4435. -

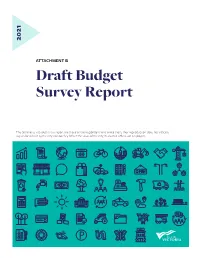

Attachment B 2021 Draft Budget Survey Report.Pdf

2021 ATTACHMENT B Draft Budget Survey Report The comments included in this report are those of the respondent who wrote them; their reproduction does not indicate any endorsement by the City, nor do they reflect the views of the City, its elected officials or employees. Have Your Say : Summary Report for 07 December 2020 to 11 January 2021 ENGAGEMENT TOOL: SURVEY TOOL Your City Budget. Have Your Say. A strategic objective is a high-level goal that Council hopes to achieve. The 2019-2022 Strategic Plan was developed and approved by Council and includes the following eight strategic objectives. Please rank the City’s Strategic Objectives from most to least important, with 1 being most important and 8 being least. OPTIONS AVG. RANK Affordable Housing 3.04 Climate Leadership and Environmental Stewardship 4.07 Reconciliation and Indigenous Relations 4.24 Strong, Liveable Neighbourhoods 4.56 Health, Well-Being and a Welcoming City 4.82 Good Governance and Civic Engagement 4.89 Sustainable Transportation 4.91 Prosperity and Economic Inclusion 5.35 Optional question (674 response(s), 35 skipped) Question type: Ranking Question Have Your Say : Summary Report for 07 December 2020 to 11 January 2021 From your perspective, what are the most important priorities facing our city right now? 1 being the most important and 9 being the least important. OPTIONS AVG. RANK Housing (affordable, rental, missing middle) and homelessness 2.75 Health, well-being and social issues 3.74 Climate action and sustainability 4.41 Economic recovery and jobs 4.65 Equity and -

Bicycles Welcome

Bicycles WelcoME How To Attract People on Bikes to Your Business! Bicycles WelcoME training generously sponsored by About BikeMaine BikeMaine promotes bicycling through a week-long tour celebrating Maine people, places, culture and food. • Route approximately 350 miles • Different route each year • Ridership currently capped at 400 • Event gives back to the local communities that host BikeMaine Bicycle Coalition of Maine - Partnership Proposal | 10 Host Communies: Sept. 9: Skowhegan Sept. 10: PiBsfield Sept. 11: Kingfield Sept. 12&13: Rangeley Sept. 14: Harord Sept. 15: Farmington Maine Tourism Maine’s Tourism Market in 2016 • 35.8 million tourists • $5.99 billion in total direct tourism expenditures Maine Office of Tourism, 2016 Overnight Tourism in Maine in 2016 • 19 million overnight tourists • Contributed $4.5 billion to Maine’s economy • Supported 106,000 jobs Maine Office of Tourism, 2016 How to Grow Tourism $$$ • Convert number of dayme visitors to overnight visitors • Aract new groups of visitors by highlighng new acvies Bicycling is a Growth Market Most Popular Outdoor Activities by Participation Rate, Ages 25+ 1. Running, Jogging and Trail Running: 14.9% 2. Fishing (Fresh, Salt and Fly): 14.6% 3. Hiking: 12.5% 4. Bicycling (Road, Mountain and BMX) 12.3% of American adults, 26.1 million participants 5. Camping (Car, Backyard, Backpacking and RV): 11.8% Source: 2016 Outdoor Recreaon Parcipaon Report Favorite Adult Activity Based on Frequency of Participation 1. Running, Jogging and Trail Running 87.1 average outings per runner 2. Bicycling (Road, Mountain and BMX) 54.2 average outings per cyclist, 1.4 billion total outings 3. -

Conversion from a Non-Profit to For-Profit Organization

Conversion from a Non-profit to For-profit Organization Case: Couchsurfing LAHTI UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Degree programme in International Business Thesis Autumn 2016 Anna Pogrebniak Lahti University of Applied Sciences Degree Programme in Business Administration POGREBNIAK, ANNA: Conversion from a Non-Profit to For-Profit Organization Case: Couchsurfing Bachelor’s Thesis in International Business 70 pages, 5 pages of appendices Autumn 2016 ABSTRACT Sharing economy has changed the way we consume, encouraging us to redistribute unused assets. Development of the Internet allowed creating platforms, engaging the exchange of goods and networks. As consumers want to exchange not only for financial profit, such services as Couchsurfing started to appear, engaging developing networks with the common interests and spending quality time. The aim of this thesis is to research how non-profit and for-profit communities compare and how conversion from non-profit to for-profit organisation influences the community itself. The final goal is to acknowledge which challenges the case company came across during the conversion process, as well as to study how its virtual community operated before and after. The author proceeds with inductive reasoning, using qualitative and quantitative methodology. Secondary data includes peer-reviewed literature and articles. Primary data is presented by the interviews and two questionnaires, conducted before and after the theoretical research. The researcher uses the case study as the main research method. The results are analysed together, highlighting the former and current issues of the community. The thesis concludes that despite several issues, Couchsurfing community is developing under the management of self-proclaimed volunteers but the services lack organized management and cooperation between activists and the actual company management board. -

WARM SHOWERS at the Augusta Canal National

News you can use from the world of bicycle travel by Michael McCoy A RAIL-TRAIL FOR ADVENTURE DOWN UNDER EACH YEAR Crossing the outback by bike with heat, wind, and flies Adventure Cycling member Robert Youker, a 75-year- old World Bank retiree from Edward Re from Australia Bethesda, Maryland, has rid- contacted Waypoints recently den “… a bit more than 75 to tell us about the cycling rail-trails,” he says. Because adventure some friends of his, Robert is such a rail-trail devo- Dave and Tim, were undertak- tee, we asked him to tell us ing. The “Gulf 2 Gulf 0309” about four of his favorites. He ride crossed the arid Australian agreed, prefacing it with this: WayPoints outback from Port Augusta, “My prime criteria are attrac- South Australia, to Karumba, tive surroundings and things Queensland. to see, and I wanted to pick OSS The pair set out on Sunday, MAYORS R a geographically dispersed March 22, and finished up group.” Here goes: ACROSS about a month later. A big Le P’tit Train du Nord Linear AMERICA piece of their route involved Park, Quebec (www.lauren Mayors Across America is a the challenging Birdsville tides.com). 200 kilometers, new book out from Ed Morris, COURTESY OF BRUCE Track, which began life in the paved. Old Canadian Pacific a California-based commercial 1880s as a stock route linking route north of Montreal runs photographer who has ridden the outposts of Birdsville and up 30 litres of water to get us them. They offered to fill a tank past Mont Tremblant and along the Northern Tier Route not Marree. -

Chainwheel Chatter the Monthly Newsletter of B.I.K.E.S

www.bikesclub.org B.I.K.E.S. Club of Snohomish County Chainwheel Chatter The Monthly newsletter of B.I.K.E.S. Club of Snohomish County Your Snohomish County Cycling Club Next B.I.K.E.S. Club meeting on March 9th @ 7:00 pm Prez Sez...Secretary Sez! RIDE GUIDE PACE Easy under 10 mph Springing Ahead Social 10–12 mph Steady 12-14 mph It just keeps betting better; more daylight, warmer (and hopefully dryer) weather, which means more cy- cling! March does seem like the start of cycling season in a lot of ways, and not just because of the weath- Moderate 14-16 mph er. Coming up are some fun bike events this month, starting March 4th and 5th, with the Seattle Bike Show at Brisk 16-18 mph Century Link Field Exhibition Center. Bikes Club is sharing a booth to promote McClinchy Mile with the Ride to Strenuous > 18 mph Remember Oso organizers. Thanks to Mike Dahlstrom for heading up the details for that. Here is a link to the event, and we have sent out a code for $2.00 off the price of tickets. https://www.seattlebikeshow.com TERRAIN “A” Mostly flat: Flat or The Ride to Remember Oso is coming up March 19th, starting in Arlington. If you are able to ride and haven't gentle grades only (trails, been out that way, it's a scenic and awe inspiring route, commemorating those who were affected by the land- Norman Rd) slide.https://www.ridetorememberoso.com Bikes club has committed to helping organize and support this event, and we still need volunteers to help us with manning the rest stop table at the mid-point in Oso, and “B” Rolling: Most climbs also at the start and finish to help promote our club and McClinchy Mile coming up April 30th, and also a few are short and easy more willing to help "sag" the route. -

The Accommodation Cheat Sheet

The Accommodation Cheat Sheet This cheat sheet has all of the best websites that you should use when looking for any type of accommodation abroad. Whether you’re looking to travel for a few days or a few years, this cheat sheet will help you find the perfect accommodation whatever your budget is. Hostels/Hotels While there are many different hotel and hostel booking websites out there, I’ve found the following to be the best. ● All The Rooms - My favourite accommodation website. It searches different websites and gives you the results from all websites in a single place so you can get the best price. ● Hostel World ● Hostel Bookers ● Booking.com ● Hot Wire Free Accommodation These are the most popular websites for free accommodation around the world. This is a great way to stay with a local and teach your hosts something new. ● Couchsurfing - Stay with locals on their couch, floor or spare bed ● Global Freeloaders -Similar to Couchsurfing ● Hospitality Club -Similar to Couchsurfing ● Talk Talk Bnb - Teach a skill/language and stay for free ● Stay 4 Free ● Home For Swap ● Warm Showers - Specifically for cyclists ● Sleeping In Airports - A guide to the best airports to sleep in when needed Work For Free Accommodation If you’re happy to work a few hours everyday, you will be rewarded with free food and accommodation. ● WWOOF - Work on farms in exchange for free accommodation Copyright 2017 - Move Your Life Abroad ● Work Away - A few hours of work per day for free accommodation and food ● Help X - Work in a variety of locations in exchange for free food and accommodation ● Working Traveller -Get volunteer and paid work as you travel using your skills ● World Packers - Exchange your skill for accommodation ● List of Websites - Here is a list of all the websites similar to Work Away Au Pair In exchange for babysitting as an au pair, you’re given free accommodation and generally paid a decent wage. -

Comparing Bicyclists, Non-Bicyclists, and Bus Drivers in Glacier National Park

Comparing Bicyclists, Non-Bicyclists, and Bus 2016 Drivers in Glacier National Park Comparing Bicyclists, Non-Bicyclists, and Bus Drivers in Glacier National Park Characteristics and Opinions of Bicycling the Going-to-the-Sun Road Norma Nickerson, Ph.D., Brian Battaglia, Research Assistant; and Kara Grau, M.S. 3/18/2016 This report provides a comparison of four Glacier National Park user groups on their opinions, attitudes and knowledge of bicycling in Glacier National Park, and the impact to Montana of GNP visitors who bicycled at some point on their Montana trip. Comparing Bicyclists, Non-Bicyclists, and Bus 2016 Drivers in Glacier National Park Comparing Bicyclists, Non-Bicyclists, and Bus Drivers in Glacier National Park Characteristics and Opinions of Bicycling the Going-to-the-Sun Road Prepared by Norma Nickerson, Ph.D., Brian Battaglia, Research Assistant, Kara Grau, M.S. Institute for Tourism & Recreation Research College of Forestry and Conservation The University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812 www.itrr.umt.edu Research Report 2016-2 3/18/2016 This study was funded by the Lodging Facility Use Tax with additional assistance from the Glacier National Park Conservancy, Kalispell CVB, Glacier Country Travel Region, Whitefish CVB, and MT Office of Tourism Copyright© 2016 Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research. All rights reserved. Comparing Bicyclists, Non-Bicyclists, and Bus Drivers in Glacier 2016 National Park Abstract This report provides a comparison of four Glacier National Park (GNP) user groups on their opinions, attitudes and knowledge of bicycling in Glacier National Park. The four user groups were summer bicyclists, summer non-bicyclists, spring bicyclists, and bus drivers in the park. -

SI PARTE! Guida Vacanze 2016 a Cura Di Sofia Vassallo E Filippo Scianò Volontari Servizio Civile Nazionale Elena Benfenati Tirocinante Università Di Ferrara

Comune di Ferrara - Assessorato Cultura, Turismo e Giovani AGENZIA INFORMAGIOVANI - EURODESK SI PARTE! guida vacanze 2016 a cura di Sofia Vassallo e Filippo Scianò volontari Servizio Civile Nazionale Elena Benfenati tirocinante Università di Ferrara in collaborazione con Rita Vita Finzi Agenzia Informagiovani Ferrara, luglio 2016 “LA FINE DI UN VIAGGO E’ SOLO L’INIZIO DI UN ALTRO” J. Saramago tai pensando che è ora di prenderti una vacanza ma non hai molti soldi e non sai bene dove andare - però le Sgambe scalpitano e devi assolutamente trovare il modo di partire! Bene, allora questa è la guida che fa per te: oltre a tante informazioni pratiche, ci troverai anche consigli utili per la realizzazione del tuo viaggio nella maniera più economica - e sicura! - possibile. Non c’è augurio più bello e più grande di un anno - e di una vita! - pieni di viaggi, perché viaggiare non è solo spostarsi temporaneamente in un luogo diverso dal proprio, è immergersi in un’altra vita, è assaporare un’altra conoscenza, è regalare parte di te alle persone che incontri e ricevere in cambio parte di loro. n’altra particolarità del viaggio è di avere il potere di aprire gli orizzonti non solo fisici ma anche culturali del viag- Ugiatore, permettendogli di instaurare rapporti nuovi con quanto visto, di modificare la sua prospettiva sul mondo, di conoscere e capire; di modificare cioè le sue aspettative ed il bagaglio di conoscenze con cui era partito. Il nostro augurio? Che i vostri viaggi d’esplorazione non abbiano mai fine! Paul( Wühr) 5 introduzione 5 Vacanza o volontariato? 6 La scelta della meta 8 Sconti per i giovani 11 Muoversi: aereo, auto, autostop 13 Muoversi: treno, autobus, traghetti, bici 17 Sistemazioni 21 Luoghi e percorsi di interesse 26 Donne in viaggio 28 Documenti 30 Salute 32 Sicurezza e tutela del turista 35 VACANZA O VOLONTARIATO? 6 quota di iscrizione ed il pagamento delle spese di viag- Una esperienza di volontariato all’estero può essere gio; il soggiorno è quasi sempre offerto dalla comunità una alternativa (od una ulteriore opportunità) molto inte- ospitante. -

RICH WITHOUT MONEY © Tomi Astikainen 2016

In loving memory of Heidemarie Schwermer (1942 – 2016) RICH WITHOUT MONEY © Tomi Astikainen 2016 Illustrations: Ghassan Nassar 2 Menu of Today STARTER SOUP OF TEARS...................................................................................................4 Ending Up Under the Bridge...............................................................................................6 Next up: Food, Water and Hygiene...................................................................................11 THE ESSENTIALS...............................................................................................................12 Quick Bite: The Elixir of Life..............................................................................................13 Finger Food: Share the Abundance..................................................................................18 Full Feast: Save the Leftovers...........................................................................................22 Next up: Material Goods...................................................................................................29 MIND OVER MATTER..........................................................................................................30 Nice Trinkets: Collaborative Consumption........................................................................31 Durable Goods: Let Go of Useless Stuf............................................................................33 Precious Treasures: The Law of Attraction........................................................................37