Emerging Art Markets and the Venice Biennale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia Presents

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia presents The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History in collaboration with Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern La Biennale di Venezia President Roberto Cicutto Board Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como Director General Andrea Del Mercato THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

The Visitor As a Commercial Partner: Notes on the 58Th Venice Biennale

Daniel Birnbaum: Seventy-nine artists is a relatively limited number. Ralph Rugoff: How many did you have in yours? Daniel Birnbaum: I can’t remember. – Artforum, May 20191 01/09 The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise. Claire Fontaine – F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up, 1936 In his statement inaugurating the 58th Venice The Visitor as a Biennale, Paolo Baratta, its president, felt compelled to address the image of the event. Commercial Entitled “The Visitor as a Partner,” the statement Partner: Notes reads in part: A partial vision of the Exhibition might consider it a high-society inauguration on the 58th followed by a line six months long for “the rest of the world.” Others might consider Venice Biennale the six-month-long Exhibition the main event and the inauguration a by-product. It would be so useful if journalists would e l a come at another moment and not during n n e the “three-day event” of the “society” i B inauguration, which can only give them a e c i 2 n very partial image of the Biennale! e V e h n t i 8 a It would be useful, indeed, but it won’t happen. t 5 n e o ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊ“Our visitors have become our main h F t e n partner,” Baratta candidly adds (meaning r i o a s l “commercial partner”), to such an extent that e C t Ê o during the overcrowded opening days, many 9 N 1 : 0 r artworks were at risk of being damaged, and 2 e r n t e basic health and safety standards weren’t r b a m P followed. -

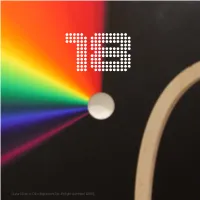

Olafur Eliasson: Color Experiment No

18 Olafur Eliasson: Color Experiment No. 29 (light spectrum) (2010). It‘s summer! The art circus has slowed down quite a bit after the manic Venice Biennale and Art Basel days - time for us at VernissageTV to prepare for the next season. Currently we are doing some maintenance work on some of the videos from 2006. We are changing the servers to speed up downloads. This will take a while, I guess until September 2011, and some of the videos won‘t be accessib- le during the transformation. I‘m sorry for the inconvenience. In addition to that we are continuously working on our r3 program, bringing selected videos to High Definition or at least Standard Definition format. An updated list of r3 videos is available here: http://vernissage.tv/blog/category/series/vtv-classics-r3/ You can watch or download VernissageTV‘s videos in a lot of different ways: our website, our channels on blip.tv, YouTube, Dailymotion, and our Facebook page. Our videos are often embedded on blogs and partner websites. We recently star- ted working with Huffington Post Arts, where you will find selected videos by VernissageTV. Our page on HuffPost Arts is: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ vernissagetv We are very happy with this, have a look! In the last months we were lucky to add great new correspondents to our team. Now we are looking for interns in New York and Los Angeles. If you are interested or know someone who might be interested, let us know by sending an e-mail to Karolina at karolina at vernissage.tv I will be in New York and Los Angeles myself. -

Catalog Vernissagetv Episodes & Artists 2005-2013

Catalog VernissageTV Episodes & Artists 2005-2013 Episodes http://vernissage.tv/blog/archive/ -- December 2013 30: Nicholas Hlobo: Intethe at Locust Projects Miami 26: Guilherme Torres: Mangue Groove at Design Miami 2013 / Interview 25: Gabriel Sierra: ggaabbrriieell ssiieerrrraa / Solo show at Galería Kurimanzutto, Mexico City 23: Jan De Vliegher: New Works at Mike Weiss Gallery, New York 20: Piston Head: Artists Engage the Automobile / Venus Over Manhattan in Miami Beach 19: VernissageTV’s Best Of 2013 (YouTube) 18: Héctor Zamora: Protogeometries, Essay on the Anexact / Galería Labor, Mexico City 17: VernissageTV’s Top Ten Videos of 2013 (on Blip, iTunes, VTV) 13: Thomas Zipp at SVIT Gallery, Prague 11: Tabor Robak: Next-Gen Open Beta at Team Gallery, New York 09: NADA Miami Beach 2013 Art Fair 07: Art Basel Miami Beach Public 2013 / Opening Night 06: Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) Preview 05: Art Basel Miami Beach 2013 04: Design Miami 2013 03: Untitled Art Fair Miami Beach 2013 VIP Preview 02: Kris Kuksi: Revival. Solo exhibition at Joshua Liner Gallery, New York November 2013 29: LoVid: Roots No Shoots / Smack Mellon, New York 27: Riusuke Fukahori: The Painted Breath at Joshua Liner Gallery, New York 25: VTV Classics (r3): VernissageTV Drawing Project, Scope Miami (2006) 22: VTV Classics (r3): Bruce Nauman: Elusive Signs at MOCA North Miami (2006) 20: Cologne Fine Art 2013 20: Art Residency – The East of Culture / Another Dimension 15: Dana Schutz: God Paintings / Contemporary Fine Arts, CFA, Berlin 13: Anselm Reyle and Marianna Uutinen: Last Supper / Salon Dahlmann, Berlin 11: César at Luxembourg & Dayan, New York 08: Artists Anonymous: System of a Dawn / Berloni Gallery, London 06: Places. -

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

V VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA The city of Vancouver is truly of the 20th century. When the small town of Granville was incorporated as the city of Vancouver in 1886, it had more in common with American cities west of the Rocky Mountains than with the rest of Canada. San Francisco had served as Vancouver’s main link to the east before the completion of Canada’s transcontinental railway in 1887. Within five years the community of 1000 had grown to nearly 14,000 and the young city became a supply depot and investment center for the Klondike gold rush of 1897–98. From these boomtown beginnings, metropolitan Vancouver is now home to more than 1.8 million people. During the early 20th century, rapid growth fueled construction of neighborhoods along the street railway and interurban lines. Before 1910 many homes were constructed of a prefabricated, insulated, four-foot modular system, designed and manufactured by the B.C.Mills, Timber, and Trading Company. Known as Vancouver Boxes, these efficient and economical houses were characterized by a single story set on a high foundation, a hip roof with dormer windows, and a broad front veranda. From 1910 until the mid-1920s, the most popular house for middle- and lower-class families was a variant of the California bungalow, typified by front gables, exposed rafter ends, and wall brackets, and often chimneys, porch piers, and foundations of rough brick or stone. These Craftsman homes, a small-scale version of the Queen Anne style, were popular amongst the suburban working classes. At one point South Vancouver was expanding at a rate of 200 families per month, all housed in California bungalows. -

2010 | Archipel

Hotel 2010 San Marco Giardini | ARCH IPEL VAPORETTO ROUTE GIARDINI 3 5 8 4 7 1 6 2 9 10 Nordic Countries Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 1958 Sverre FEHN 1 In 1958 a competition is held for the design of the Nordic Countries Pavilion for the Venice Biennale (to host Sweden, Norway and Finland). Three architects are invited: the swed- ish Klas Anshelm, the norwegian Sverre Fehn and the finnish Reima Pietila. In 1959 Sverre Fehn is declared winner and by 1962 the Pavilion is completed. The pavilion is a single rec- tangular hall of 400 sqm, open completely on two sides. The roof is made of two overlapping layers of concrete beams. The distance between the beams is 52,1 cm and this changes only when the roof meets the trees. The pavilion is an example of the disappearing transition between interior and exterior. Venezuelan Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 1953 Carlo SCARPA 2 In 1953 Graziano Gasparini, Venezuelan commissioner for the Biennale, asked Carlo Scarpa to design a pavilion for Venezuela. In January 1954, the pavilion design is approved and the structure is roughly completed by October, while the XXVII Biennale is finishing. Only by 1956 the pavilion finishings are completed. It is conceived as three volumes sliding against each other. The form is simple and realized in rough concrete. Austrian Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 1934 Joseph Hoffmann 3 The first draft for the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was sketched by Josef Hoffmann in 1913. The project ended up being too costly and eventually the idea was abandoned. -

Architecture NZ AR05, 2018

Reviews UP ON THE ROOF IN VENICE The theme of Biennale Architettura 2018 is FREESPACE, meaning “a generosity of spirit and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture’s agenda” – and while New Zealand didn’t host an exhibition this time around, Colin Martin reports back on the rest of the world’s offerings. IT CAN BE CHALLENGING TO SEE THE WOOD FOR At the Corderie, the materiality of architecture is the trees at international architecture exhibitions but La demonstrated by the exhibiting architectural practices’ varied Biennale di Venezia’s curators Yvonne Farrell and Shelley choices of timber, metal, concrete, stone, glass or textiles in McNamara have made that task easier in 2018. Their manifesto, constructing large-scale installations. Many of their structures asserting that “such an exhibition can remind us in a very are double-height, and allow access to upper levels. Highlights intense way that architecture is essential for the well-being include: the skilful manipulation of natural light by Flores of societies, where good examples of buildings matter – not & Prats (Spain) to animate the central circulation space of only in themselves – but as living ‘proof’ that architecture is a Barcelona theatre and drama centre, created within an a gift to humanity”, augured well. Their curated exhibitions abandoned workers cooperative building; a protective roof over at the Arsenale and Giardini have delivered on that promise, a Chinese spring water source by Jensen & Skodvin Architects 01 and 02 celebrating the physicality of built architecture rather than (Norway); and a spectacular clifftop house restoration and a Protective Roof reiterating architectural theories. -

A Strong Social and Political Critique / the 52Nd Venice Biennale: Entitled Think with the Senses — Feel with the Mind

Document generated on 10/01/2021 10:47 a.m. ETC A strong social and political critique The 52nd Venice Biennale: entitled Think with the Senses — Feel with the Mind. Art in the Present Tense. 10 June - 21 November, 2007 Maria Zimmermann Brendel Spectateur/Spectator Number 80, December 2007, January–February 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/35084ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Revue d'art contemporain ETC inc. ISSN 0835-7641 (print) 1923-3205 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Zimmermann Brendel, M. (2007). Review of [A strong social and political critique / The 52nd Venice Biennale: entitled Think with the Senses — Feel with the Mind. Art in the Present Tense. 10 June - 21 November, 2007]. ETC, (80), 67–72. Tous droits réservés © Revue d'art contemporain ETC inc., 2007 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Venice A STRONG SOCIAL AND POLITICAL CRITIQUE The 52' Venice Biennale entitled Think with the Senses. - Feci with the Mind. Art i n the Present Tense. 10 June - 21 November, 2007 hat makes a good exhibition, is not that other like a spider-web into which viewers had to step in order it differs in all categories from the previ to proceed.