Narrative on Anthony Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antonis Antoniou · Kkismettin · Ajabu!

JULY 2021 Antonis Antoniou · Kkismettin · Ajabu! 2. Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino (CGS) · Meridiana · 22. Apo Sahagian · Ler Mer · Chimichanga (-) Ponderosa Music (1) 23. Katerina Papadopoulou & Anastatica · Anastasis · 3. Toumani Diabaté and The London Symphony Orchestra · Saphrane (19) Kôrôlén · World Circuit (10) 24. BLK JKS · Abantu / Before Humans · Glitterbeat (-) 4. Ballaké Sissoko · Djourou · Nø Førmat! (2) 25. Davide Ambrogio · Evocazioni e Invocazioni · Catalea 5. Ben Aylon · Xalam · Riverboat / World Music Network (6) (-) 6. Dobet Gnahoré · Couleur · Cumbancha (-) 26. Saucējas · Dabā · Lauska / CPL-Music (31) 7. Balkan Taksim · Disko Telegraf · Buda Musique (5) 27. V.A. · Hanin: Field Recordings In Syria 2008/2009 · 8. V.A. · Henna: Young Female Voices from Palestine · Kirkelig Worlds Within Worlds (-) Kulturverksted (-) 28. Juana Molina · Segundo (Remastered) · Crammed Discs 9. Samba Touré · Binga · Glitterbeat (3) (-) 10. Jupiter & Okwess · Na Kozonga · Zamora Label (7) 29. Bagga Khan · Bhajan · Amarrass (15) 11. Kasai Allstars · Black Ants Always Fly Together, One Bangle 30. Alena Murang · Sky Songs · Wind Music International Makes No Sound · Crammed Discs (12) Corporation (-) 12. Sofía Rei · Umbral · Cascabelera (-) 31. Oumar Ndiaye · Soutoura · Smokey Hormel (-) 13. Hamdi Benani, Mehdi Haddab & Speed Caravan · Nuba 32. Xurxo Fernandes · Levaino! · Xurxo Fernandes (29) Nova · Buda Musique (27) 33. Omar Sosa · An East African Journey · Otá (24) 14. Comorian · We Are an Island, but We're Not Alone · 34. San Salvador · La Grande Folie · La Grande Folie / Glitterbeat (17) Pagans / MDC (11) 15. Dagadana · Tobie · Agora Muzyka (18) 35. Helsinki-Cotonou Ensemble · Helsinki-Cotonou 16. Luís Peixoto · Geodesia · Groove Punch Studios (20) Ensemble · flowfish.music (-) 17. Femi Kuti & Made Kuti · Legacy + · Partisan (30) 36. -

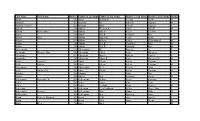

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

English Versions of Foreign Names

ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Aaron Aron . Aaron Aron Aranne Arek Aron Aaron Aron Aron Aron Aron Aronek Aronos Abel Avel . Abel Abel Abele . Avel Abel Hebel Avel Awel Abraham Braha Abram Abraham Avram Abramo Abraham . Abram Abraham Bramek Abram Abrasha Avram Abramek Abrashen Ovrum Abrashka Avraam Avraamily Avram Avramiy Avarasha Avrashka Ovram Achilies . Achille Achill . Akhilla . Akhilles Akhilliy Akhylliy Ada . Ada Ada Ara . Ariadna Page 1 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adalbert Vojta . Wojciech . Vojtech Wojtek Vojtek Wojtus Adam Adam . Adam Adam Adamo Adam Adamik Adamka Adi Adamec Adi Adamek Adamko Adas Adamek Adrein Adas Adamok Damek Adok Adela Ada . Ada Adel . Adela Adelaida Adeliya Adelka Ela AdeliAdeliya Dela Adelaida . Ada . Adelaida . Adela Adelayida Adelaide . Adah . Etalka Adele . Adele . Adelina . Adelina . Adelbert Vojta . Vojtech Vojtek Adele . Adela . Page 2 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adelina . -

Last Name First Name Birth Yrfather's Last Name Father's

Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's First Name Gender Aaron 1907 Aaron Benjaman Shields Minnie M Aaslund 1893 Aaslund Ole Johnson Augusta M Aaslund (Twins) 1895 Aaslund Oluf Carlson Augusta F Abbeal 1906 Abbeal William A Conlee Nina E M Abbitz Bertha Dora 1896 Abbitz Albert Keller Caroline F Abbot 1905 Abbot Earl R Seldorff Rose F Abbott Zella 1891 Abbott James H Perry Lissie F Abbott 1896 Abbott Marion Forder Charolotta M M Abbott 1904 Abbott Earl R Van Horn Rose M Abbott 1906 Abbott Earl R Silsdorff Rose M Abercrombie 1899 Abercrombie W Rogers A F Abernathy Marjorie May 1907 Abernathy Elmer Scott Margaret F Abernathy 1892 Abernathy Wm A Roberts Laura J F Abernethy 1905 Abernethy Elmer R Scott Margaret M M Abikz Louisa E 1902 Abikz Albert Keller Caroline F Abilz Charles 1903 Abilz Albert Keller Caroline M Abircombie 1901 Abircombie W A Racher Allos F Abitz Arthur Carl 1899 Abitz Albert Keller Caroline M Abrams 1902 Abrams L E Baker May F Absher 1905 Absher Ben Spillman Zoida M Achermann Bernadine W 1904 Ackermann Arthur Krone Karolina F Acker 1903 Acker Louis Carr Lena F Acker 1907 Acker Leyland Ryan Beatrice M Ackerman 1904 Ackerman Cecil Addison Willis Bessie May F Ackermann Berwyn 1905 Ackermann Max Mann Dolly M Acklengton 1892 Achlengton A A Riacting Nattie F Acton Rebecca Elizabeth 1891 Acton T M Cox Josie E F Acton 1900 Acton Chas Payne Minnie M Adair Elles 1906 Adair Adel M Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's -

Silver Spring

DISTRICT COURT WEB DOCKET FOR - SILVER SPRING This report was run on 9/27/2021 8:20:04 PM and is subject to change. The dockets are updated at 9:00PM Monday through Friday. You may need to refresh the report to receive the latest update. On your court date, check the docket boards located in the court for any updates. The clerks update the docket boards with the correct room numbers the day of trial. Silver Spring Hearing Date: 09/28/2021 - Tuesday Party Name Case Number Hearing Time Courtroom Remote Hearing Details ABDELAZIZ, MOHAMED HAMDY 015H0PH4 11:00AM Courtroom 301 ALANIZ, DIANA /RODRIGUEZ, GILDA 0602SP002302021 03:30PM Courtroom 512 ES ANDERSON, ASHLEY /HALLIVIS, 0602SP002272021 02:30PM Courtroom 512 ALBERT ANOBAH, SAMUEL OTOO JR 00PG0PJF 10:00AM Courtroom 301 ANOBAH, SAMUEL OTOO JR 00PH0PJF 10:00AM Courtroom 301 ANOBAH, SAMUEL OTOO JR 00PJ0PJF 10:00AM Courtroom 301 ANOBAH, SAMUEL OTOO JR 00PK0PJF 10:00AM Courtroom 301 ANOBAH, SAMUEL OTOO JR 00PL0PJF 10:00AM Courtroom 301 ANOBAH, SAMUEL OTOO JR 00PM0PJF 10:00AM Courtroom 301 ANTAR, ZEINA IBRAHIM 004V0TZK 01:30PM Courtroom 301 BALLON, CESAR ROBERTO 00N30PJF 09:00AM Courtroom 301 BALLON, CESAR ROBERTO 00N40PJF 09:00AM Courtroom 301 BALLON, CESAR ROBERTO 00N50PJF 09:00AM Courtroom 301 BALLON, CESAR ROBERTO 00N60PJF 09:00AM Courtroom 301 BALLON, CESAR ROBERTO 00N70PJF 09:00AM Courtroom 301 BARKER, JOHNIE LEE 00B00PP8 10:00AM Courtroom 301 BARKER, JOHNIE LEE 00B10PP8 10:00AM Courtroom 301 BENITEZ, JOSE CESAR 013B0QQC 11:00AM Courtroom 301 BENOIT, PATRICK G 00Q80S1B 11:00AM Courtroom -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

Antony Blinken U.S. Secretary of State Nominee Office of the President Elect 1401 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20230 S

Antony Blinken Secretary John Kerry U.S. Secretary of State Nominee Special Presidential Envoy for Climate Designate Office of the President Elect Office of the President Elect 1401 Constitution Avenue NW 1401 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20230 Washington, DC 20230 Dear Secretary of State Nominee Blinken and Secretary Kerry: We, the undersigned landscape architects, design professionals, and other stewards of the built and natural environments, are writing to urge you to recommit to the United States’ promise to the Paris Climate Agreement of the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change. The United States must act quickly and diligently to reverse our climate change impacts while working to build a more sustainable and resilient future for all. We also urge you to develop global climate action approaches that heavily use green infrastructure, nature-based solutions, and other low-impact development strategies. The findings in the 2018 UN Climate Change Annual Report state that green infrastructure is one of the world’s greatest tools to create a more sustainable future. Additionally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C highlights the importance of green infrastructure, sustainable land use and water management, and nature-based solutions as important adaptation options to reduce the risks and perils related to climate change. As the Biden-Harris administration begins to take action on this issue, we hope you heed these findings to create a more climate-resilient and sustainable planet. Landscape architects are leaders in using green infrastructure and nature-based solutions to plan and design projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and make communities more resilient to climate impacts. -

Names Meanings

Name Language/Cultural Origin Inherent Meaning Spiritual Connotation A Aaron, Aaran, Aaren, Aarin, Aaronn, Aarron, Aron, Arran, Arron Hebrew Light Bringer Radiating God's Light Abbot, Abbott Aramaic Spiritual Leader Walks In Truth Abdiel, Abdeel, Abdeil Hebrew Servant of God Worshiper Abdul, Abdoul Middle Eastern Servant Humble Abel, Abell Hebrew Breath Life of God Abi, Abbey, Abbi, Abby Anglo-Saxon God's Will Secure in God Abia, Abiah Hebrew God Is My Father Child of God Abiel, Abielle Hebrew Child of God Heir of the Kingdom Abigail, Abbigayle, Abbigail, Abbygayle, Abigael, Abigale Hebrew My Farther Rejoices Cherished of God Abijah, Abija, Abiya, Abiyah Hebrew Will of God Eternal Abner, Ab, Avner Hebrew Enlightener Believer of Truth Abraham, Abe, Abrahim, Abram Hebrew Father of Nations Founder Abriel, Abrielle French Innocent Tenderhearted Ace, Acey, Acie Latin Unity One With the Father Acton, Akton Old English Oak-Tree Settlement Agreeable Ada, Adah, Adalee, Aida Hebrew Ornament One Who Adorns Adael, Adayel Hebrew God Is Witness Vindicated Adalia, Adala, Adalin, Adelyn Hebrew Honor Courageous Adam, Addam, Adem Hebrew Formed of Earth In God's Image Adara, Adair, Adaira Hebrew Exalted Worthy of Praise Adaya, Adaiah Hebrew God's Jewel Valuable Addi, Addy Hebrew My Witness Chosen Addison, Adison, Adisson Old English Son of Adam In God's Image Adleaide, Addey, Addie Old German Joyful Spirit of Joy Adeline, Adalina, Adella, Adelle, Adelynn Old German Noble Under God's Guidance Adia, Adiah African Gift Gift of Glory Adiel, Addiel, Addielle -

Marc Antony's Assault of Publius Clodius

MARC ANTONY’S ASSAULT OF PUBLIUS CLODIUS: FACT OR CICERONIAN FICTION? Dean Anthony Alexander (University of Otago) Introduction: Cicero and Truthfulness On account of Asconius’ commentary In Milonianam, scholars have been able to appreciate fully the artful mendacity and dexterous factual manipulation that Cicero employs in his Pro Milone.1 It becomes apparent Cicero believed advocates had the latitude to lie in defence of their client, and could employ what Horace would later term the ‘shining untruth’ (splendide mendax).2 It is for this reason, therefore, that I intend to examine a dubious allegation that Cicero first promotes in his Pro Milone, one which is still widely regarded as true: namely that Marc Antony tried to assassinate Publius Clodius Pulcher in 53 BC.3 This paper seeks to argue that, based on the surviving evidence, Cicero either misrepresents some minor altercation or, perhaps, even invented the episode entirely. While almost all modern scholars accept Cicero’s claim there are, as will be seen, several anomalies that call his charge into question.4 Most notably, if Antony did make a genuine assassination attempt, why, in the wake of Clodius’ actual murder, was he appointed subscriptor to prosecute Milo in 52 BC? Scholars such as Jerzy Linderski and John T. Ramsey have unconvincingly characterized this as an opportunistic volte-face on Antony’s part.5 Even if this were true, however, it does not explain convincingly why Clodius’ family would allow him to participate in the prosecution, if he were estranged from Clodius as Cicero alleges.6 This alone leads one to suspect that Cicero has either misrepresented or even invented the story to discredit Antony. -

Metropolitan Police Department, Washington.D.C

General Question #7 Metropolitan Police Department, Washington.D.C. DATA SUMMARY - Cellular Distribution by Bureau (Includes only Active Devices) Bureau Device Count Corporate Support Bureau 25 Executive Office of the Chief of Police 84 Homeland Security Bureau 134 Internal Affairs Bureau 38 Investigative Service Bureau 463 Patrol Services Bureau 658 Strategic Services Bureau 23 Overall - Total 1,425 Total cost across all Vendors by Fiscal year Vendor 2016 2015 2014 AT&T Wireless $1,140.60 $5,419.83 $4,441.09 VERIZON WIRELESS $155,520.12 $850,943.34 $577,326.84 Cost - Total $156,660.72 $856,363.17 $581,767.93 Device Count across all Vendors by Fiscal Year (Includes only Active Devices) Vendor 2016 2015 2014 AT&T Wireless 2 2 2 VERIZON WIRELESS 1,428 1,279 734 Overall - Total 1,430 1,281 736 This report was run on Apr 5, 2016-2:31:22 PM. The data content is based upon the available values found in the MPD Datawarehouse at the time when it was run. Page 1/4 Metropolitan Police Department, Washington.D.C. DATA SUMMARY - Pager Distribution by Bureau (Includes only Active Devices) Bureau Device Count Corporate Support Bureau 0 Executive Office of the Chief of Police 0 Homeland Security Bureau 22 Internal Affairs Bureau 1 Investigative Service Bureau 0 Outside Agency 0 Patrol Services Bureau 1 Strategic Services Bureau 0 Overall - Total 24 Total cost across all Vendors by Fiscal year Vendor 2016 2015 2014 SPOK (formerly USA Mobility) $10,412.74 $62,631.29 $57,967.99 Cost - Total $10,412.74 $62,631.29 $57,967.99 Device Count across all Vendors by Fiscal Year (Includes only Active Devices) Vendor 2016 2015 2014 SPOK (formerly USA Mobility) 24 24 24 Overall - Total 24 24 24 This report was run on Apr 5, 2016-2:31:22 PM. -

Saints' Lives and Bible Stories for the Stage

Saints’ Lives and Bible Stories for the Stage ANTONIA PULCI • Edited by ELISSA B. WEAVER Translated by JAMES WYATT COOK Iter Inc. Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Toronto 2010 Iter: Gateway to the Middle Ages and Renaissance Tel: 416/978–7074 Fax: 416/978–1668 Email: [email protected] Web: www.itergateway.org CRRS Publications, Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria University in the University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario M5S 1K7 Canada Tel: 416/585–4465 Fax: 416/585–4430 Email: [email protected] Web: www.crrs.ca © 2010 Iter Inc. & the Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies All Rights Reserved Printed in Canada We thank the Gladys Kriebel Delmas Foundation for a generous grant of start-up funds for The Other Voice, Toronto Series, a portion of which supports the publication of this volume. Iter and the Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies gratefully acknowledge the generous sup- port of James E. Rabil, in memory of Scottie W. Rabil, toward the publication of this book. “The Play of Saint Francis,” “The Play of Saint Domitilla,” “The Play of Saint Guglielma,” and “The Play of the Prodigal Son” used with permission from Cook, James Wyatt, and Barbara Collier Cook, eds. Floren- tine Drama for Convent and Festival: Seven Sacred Plays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe. © 1996 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Pulci, Antonia, 1452–1501 Saints’ lives and Bible stories for the stage / Antonia Pulci ; edited by Elissa B. -

ANTONIUS GUAINERIUS on EPILEPSY* by WILLIAM G

ANTONIUS GUAINERIUS ON EPILEPSY* By WILLIAM G. LENNOX, M.D. BOSTON nfortu nately , infor- chamberlain, Andrea de Birago. The mation about Antonius Gu- work on pests and poisons was com- ainerius (Antonio Guaineri) posed about 1440, since in that year a is very scanty. We know copy was made by Nicolaus Ofhuys of that he lectured in the UniversityAmsterdam. of There is a suggestion of his UPavia near the beginning of the fifteenth interest in politics in the fact that in his century. As with many historical frag- preface to his tract on pests he appeals ments, certain small details have been to the duke of Milan to save “our perfectly preserved, whereas the facts Liguria.” usually important, such as dates of birth These medical writings give no in- and death, honors and nonprofessional formation about Guainerius as a man. activities, are absent. For example, One of his fifteenth century manuscripts Maiocchi (1) states that he lectured has the name of Theodori Guaynerii de at the University in the early after- Papia on the fly leaf and on the reverse noon in the year 1412-13, receiving for the statement that the work was com- this a total of one hundred and twenty posed by Antonius Guaynerius de florins. Thirty-six years later, in 1448, Papia, “my ancester” (genitor meus). he gave the lecture in medicine in the Therefore we may conclude that An- late afternoon, the salary having risen tonius was a family man. to three hundred florins with a prospect Neuburger (2) places the death of of receiving twenty-five more in the Guainerius about 1445, Sudhoff (3) in following year.