Pieter Hugo. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art at the Silo Hotel a Brief History

ART AT THE SILO HOTEL A BRIEF HISTORY The history of Africa is the history of being plundered for its most valuable resources. This was exemplified by the original grain silo building in Table Bay from which grain was exported to Europe. The new building represents a showcase retaining Africa’s greatest creative resources. The building itself can be seen as a work of art, offering it’s beautifully reimagined structure as an industrial canvas that highlights the very best of African art and design. “I have always included wonderful art at each of The Royal Portfolio properties. Art brings a space Liz Biden, owner of The Royal Portfolio pays tribute to this vision, through her use of to life, it creates warmth and tells stories. But moreover, art takes you on a journey which evolves contemporary African art and local craftsmanship in her interior design of The Silo as we evolve. Our guests love to enjoy the art collection at our properties. The Silo Hotel will take Hotel. that art experience to a whole new level with a focus on contemporary African art…” LIZ BIDEN During her trips throughout Africa, aided by her well-travelled eye for the exquisite FOUNDER AND OWNER and the unusual, Liz Biden has acquired a unique and varied collection of art that complements that of Zeitz MOCAA situated below The Silo Hotel. Highlighting both young, aspiring artists, as well as established, highly acclaimed artists such as Cyrus Kabiru, Mahau Modisakeng and Nandipha Mntambo. Liz Biden has specifically chosen pieces to complement the unique interiors of each of the 28 rooms, offering individualised experiences for guests and many a reason to return. -

PERSPECTIVES 2 5 March – 11 April 2015

PERSPECTIVES 2 5 MARch – 11 APRIL 2015 Perspectives 2 Perspectives 2 – as its title suggests, the second in a His Presence, a painting first shown in the Zimbabwean series of group exhibitions titled Perspectives – features Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale (2013). Moshekwa works by Walter Battiss, Zander Blom, David Goldblatt, Langa’s trance-like paintings similarly imagine a realm Pieter Hugo, Anton Kannemeyer, Moshekwa Langa, beyond comprehension, and the sparse black gestures Stanley Pinker, Robin Rhode, Penny Siopis of Zander Blom’s Untitled [1.288] draw inspiration from and Portia Zvavahera. the mark-making of South African modernist Ernest Mancoba’s lifelong meditation on the essence Many of the works included in Perspectives 2 have been of human form. exhibited in the gallery over the past 12 years; others by gallery artists were exhibited further afield. They return to A group of works picture scenes of pleasure. Stanley be offered to new collectors to start new conversations, and Pinker’s The Bather is a small, joyous painting of a nude from this group several themes emerge. sitting alongside a lake, and is a portrait of intimacy and relaxation calmingly rendered in a spring palette. Battiss’ The notion of seriality is prominent. Walter Battiss’ colourful renderings of women from the Bajun Islands watercolours painted at Leisure Bay in KwaZulu-Natal are on the Kenyan coast, and his watercolours of Leisure studies of colour and light at different times of the day. Bay, his holiday destination, offer comparably hedonistic Zander Blom’s large-scale abstract painting Untitled [1.300] sensibilities. This motif extends to the primary-coloured offers repetition in mark-making and so allows the viewer’s nude gathering in Battiss’ sgraffito oil on canvas Figures eye to circulate through it. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

South African Photography of the HIV Epidemic

Strategies of Representation: South African Photography of the HIV Epidemic Annabelle Wienand Supervisor: Professor Michael GodbyTown Co-supervisor: Professor Nicoli Nattrass Cape Thesis presentedof for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Visual and Art History Michaelis School of Fine Art University of Cape Town University February 2014 University of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University This thesis is dedicated to Michael Godby and Nicoli Nattrass Abstract This thesis is concerned with how South African photographers have responded to the HIV epidemic. The focus is on the different visual, political and intellectual strategies that photographers have used to document the disease and the complex issues that surround it. The study considers the work of all South African photographers who have produced a comprehensive body of work on HIV and AIDS. This includes both published and unpublished work. The analysis of the photographic work is situated in relation to other histories including the history of photography in Africa, the documentation of the HIV epidemic since the 1980s, and the political and social experience of the epidemic in South Africa. The reading of the photographs is also informed by the contexts where they are published or exhibited, including the media, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and aid organisations, and the fine art gallery and attendant publications. -

Prix Pictet Disorder Shortlist Press Release English

PRESS RELEASE Embargoed for publication: 19.00 hrs 10 July 2015 SHORTLIST ANNOUNCED FOR WORLD’S TOP PHOTOGRAPHY PRIZE The shortlist of twelve photographers selected for the sixth Prix Pictet, Disorder, is announced today, Friday 10 July 2015. The photographers are: Ilit Azoulay, born Jaffa 1972, lives and works Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Israel Valérie Belin, born Boulogne-Billancourt 1964, lives and works Paris, France Matthew Brandt, born Los Angeles 1982, lives and works Los Angeles, USA Maxim Dondyuk, born Polyan’ 1983, lives and works Kiev, Ukraine Alixandra Fazzina, born London 1974, lives and works London, UK Ori Gersht, born Tel Aviv 1967, lives and works London, UK John Gossage, born New York 1946, lives and works Washington DC, USA Pieter Hugo, born Johannesburg 1976, lives and works Cape Town, South Africa Gideon Mendel, born Johannesburg 1959, lives and works London, UK Sophie Ristelhueber, born Paris 1949, lives and works Paris, France Brent Stirton, born Durban 1969, lives and works New York, USA Yang Yongliang, born Shanghai 1980, lives and works Shanghai, China The winner of the Prix Pictet will be announced by Honorary President Kofi Annan on 12 November 2015, on the occasion of the opening of an exhibition of works by the twelve shortlisted photographers at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Now in its sixth cycle, the Prix Pictet was founded by the Pictet Group in 2008. Today the Prix Pictet is recognised as the world’s leading prize for photography. On an 18-month cycle the award focuses on a theme that promotes discussion and debate on issues of sustainability. -

7.10 Nov 2019 Grand Palais

PRESS KIT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST, YANCEY RICHARDSON, NEW YORK, AND STEVENSON CAPE TOWN/JOHANNESBURG CAPE AND STEVENSON NEW YORK, RICHARDSON, YANCEY OF THE ARTIST, COURTESY © ZANELE MUHOLI. © ZANELE 7.10 NOV 2019 GRAND PALAIS Official Partners With the patronage of the Ministry of Culture Under the High Patronage of Mr Emmanuel MACRON President of the French Republic [email protected] - London: Katie Campbell +44 (0) 7392 871272 - Paris: Pierre-Édouard MOUTIN +33 (0)6 26 25 51 57 Marina DAVID +33 (0)6 86 72 24 21 Andréa AZÉMA +33 (0)7 76 80 75 03 Reed Expositions France 52-54 quai de Dion-Bouton 92806 Puteaux cedex [email protected] / www.parisphoto.com - Tel. +33 (0)1 47 56 64 69 www.parisphoto.com Press information of images available to the press are regularly updated at press.parisphoto.com Press kit – Paris Photo 2019 – 31.10.2019 INTRODUCTION - FAIR DIRECTORS FLORENCE BOURGEOIS, DIRECTOR CHRISTOPH WIESNER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR - OFFICIAL FAIR IMAGE EXHIBITORS - GALERIES (SECTORS PRINCIPAL/PRISMES/CURIOSA/FILM) - PUBLISHERS/ART BOOK DEALERS (BOOK SECTOR) - KEY FIGURES EXHIBITOR PROJECTS - PRINCIPAL SECTOR - SOLO & DUO SHOWS - GROUP SHOWS - PRISMES SECTOR - CURIOSA SECTOR - FILM SECTEUR - BOOK SECTOR : BOOK SIGNING PROGRAM PUBLIC PROGRAMMING – EXHIBITIONS / AWARDS FONDATION A STICHTING – BRUSSELS – PRIVATE COLLECTION EXHIBITION PARIS PHOTO – APERTURE FOUNDATION PHOTOBOOKS AWARDS CARTE BLANCHE STUDENTS 2019 – A PLATFORM FOR EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHY IN EUROPE ROBERT FRANK TRIBUTE JPMORGAN CHASE ART COLLECTION - COLLECTIVE IDENTITY -

Afrique Du Sud. Photographie Contemporaine

David Goldblatt, Stalled municipal housing scheme, Kwezidnaledi, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006, de la série Intersections Intersected, 2008, archival pigment ink digitally printed on cotton rag paper, 99x127 cm AFRIQUE DU SUD Cours de Nassim Daghighian 2 Quelques photographes et artistes contemporains d'Afrique du Sud (ordre alphabétique) Jordi Bieber ♀ (1966, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) www.jodibieber.com Ilan Godfrey (1980, Johannesburg ; vit à Londres, Grande-Bretagne) www.ilangodfrey.com David Goldblatt (1930, Randfontein, Transvaal, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Kay Hassan (1956, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) Pieter Hugo (1976, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) www.pieterhugo.com Nomusa Makhubu ♀ (1984, Sebokeng ; vit à Grahamstown) Lebohang Mashiloane (1981, province de l'Etat-Libre) Nandipha Mntambo ♀ (1982, Swaziland ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zwelethu Mthethwa (1960, Durban ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zanele Muholi ♀ (1972, Umlazi, Durban ; vit à Johannesburg) Riason Naidoo (1970, Chatsworth, Durban ; travaille à la Galerie national d'Afrique du Sud au Cap) Tracey Rose ♀ (1974, Durban, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Berni Searle ♀ (1964, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit au Cap) Mikhael Subotsky (1981, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Guy Tillim (1962, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Nontsikelelo "Lolo" Veleko ♀ (1977, Bodibe, North West Province ; vit à Johannesburg) Alastair Whitton (1969, Glasgow, Ecosse ; vit au Cap) Graeme Williams (1961, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Références bibliographiques Black, Brown, White. Photography from South Africa, Vienne, Kunsthalle Wien 2006 ENWEZOR, Okwui, Snap Judgments. New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, cat. expo. 10.03.-28.05.06, New York, International Center of Photography / Göttingen, Steidl, 2006 Bamako 2007. -

Pieter Hugo Kin January 14Th – April 26Th 2015 Press Opening on January 13Th from 10Am to 12Am, in the Presence of the Artist

PRESS RELEASE Pieter Hugo Kin January 14th – April 26th 2015 Press opening on January 13th from 10am to 12am, in the presence of the artist. From January 14th to April 26th, Fondation HCB is showing Kin, the last project of the south-african photographer Pieter Hugo. Through landscapes, portraits and still life photography exhibited for the first time in France, the photographer offers a personal exploration of South Africa. The exhibit, accompanied by a book published by Aperture is coproduced with Foto Colectania Foundation, Barcelone and Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg. Created over the past eight years, Pieter Hugo's series Kin confronts complex issues of colonization, racial diversity and economic disparity in Hugo's homeland of South Africa. These subjects are common to the artist's past projects in Nigeria, Ghana, Liberia and Botswana; however, this time, Hugo's attention is focused on his conflicted relationship with the people and environs closest to home. Hugo depicts locations and subjects of personal significance, such as cramped townships, contested farmlands, abandoned mining areas and sites of political influence, as well as psychologically charged still lives in people's homes and portraits of drifters and the homeless. Hugo also presents intimate portraits of his pregnant wife, his daughter moments after her birth and the domestic servant who worked for three generations of Hugo's family. Alternating between private and public spaces, with a particular emphasis on the growing disparity between rich and poor, Kin is the artist's effort to locate himself and his young family in a country with a fraught history and an uncertain future. -

Beyond Our Complexion: Albinism in Visual Culture

1 COURSE: MA RESEARCH LEVEL: MASTER OF FILM AND TELEVISION STUDIES COURSE CODE: WSOA7052 Beyond Our Complexion: Albinism in Visual culture , • Name & Student No: Didintle Mookeletsi 769336 Supervisor: Prof Jyoti Mistry Date: 18 May 2018 Declaration I declare that this research is my own, unaided work. It is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Masters in Film and Television at the University of the Witswatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree, part of degree or examination at this or any other university. My HR non-medical ethics clearance certificate number is HlS/09/19. ~ Didintle N Mookeletsi Date 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Key Informants and Characters 3 3. Theoretical Expressions for the Research Report 6 3 .1 Difference and Otherness 6 3.2 Stereotyping 7 3.3 Abjection 8 3 .4 Freakery 9 3.4.1 Rosemary Garland Thomson on Freakery 9 3.4.2 Elizabeth Grosz on Freakery 10 3.5 Fetishism 11 4 .Physical Challenges faced by People with Albinism 12 5. Skin Challenges faced by People with Albinism 13 6. Rejection faced by People with Albinism 14 7. Identity and Integration in South African Society 18 7.1 Pieter Hugo' s Photography- The Albino Portraits 18 8. Sexual exploitation of people with Albinism 20 9. How Film and Photography Portrays People with albinism 22 10. Media Culture towards People with Albinism 24 11. Beyond Our Complexion-The Film 26 12. Conclusion 28 13 . References 30 3 1. INTRODUCTION The aim of my research paper is to investigate the portrayal of albinos and albinism through visual culture in the South African context. -

Season of Migration to the North .Info

stevenson #01 06-2019 .info Wim Botha’s Prism bronzes in the garden at Stevenson Johannesburg. PHOTO: MARIO TODESCHINI Season of migration to the north # New spaces in Joburg a dog named Leni, and a lounge an art fair – and one that feels more and Amsterdam styled by Tonic Design whose studio hospitable too. is two doors down. Our first presentation, Winter As of 18 May 2019, Stevenson The new gallery opened with Sun, takes its title from a linocut Johannesburg has a new home in Portia Zvavahera’s Talitha Cumi, of an Amsterdam cityscape by Parktown North – not too far from attended by, among others, friends Peter Clarke and features artists Craighall Park where David Brodie from the Johannesburg Art Gallery, with personal connections to (formerly ArtExtra) and Michael Keleketla, the Goethe-Institut, Amsterdam and our gallery: Clarke Stevenson joined forces as Brodie/ VANSA and Pérez Art Museum himself, Breyten Breytenbach, Stevenson in 2008 (their first show: Miami. The show runs till 26 July. Meschac Gaba, Nicholas Hlobo, Athi-Patra Ruga’s ... of bugchasers Moshekwa Langa, Neo Matloga, and watussi faghags). In the Northern Hemisphere we’re Zanele Muholi, Viviane Sassen and After spending nine years on opening a space in partnership with Kemang Wa Lehulere. Juta Street, Braamfontein, our We Folk, the agency that represents Following the opening on 8 June, adoption of a turn-of-the-century the commercial work of gallery our hours will be Saturdays from 12 home in Parktown North carries artists Viviane Sassen and Pieter to 6pm, September to June, or by the pragmatic benefits of an Uber- Hugo. -

Acropolis Now: Ponte City As 'Portrait of a City'

Article Thesis Eleven 2017, Vol. 141(1) 67–85 Acropolis now: Ponte City ª The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav as ‘portrait of a city’ DOI: 10.1177/0725513617720243 journals.sagepub.com/home/the Svea Josephy University of Cape Town, South Africa Abstract Ponte City is a project by Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse that uses photo- graphs, architectural diagrams, text, interviews, fiction, found objects, oral history, and archival material to critically explore a particular urban landscape in Johannesburg. The exhibition and book, which comprise this project, manifest in different ways, but both work together to cut across disciplines and incorporate the languages of fine art, photography, architecture, urban planning, history, economics, popular culture, and literature. The publication comprises a book of photographs and pamphlets in which the artists have collaborated with former and current residents, gathered personal stories, delved into the archive, invited authors to contribute essays on a variety of topics, and worked with material found at the site. This article examines the notion of a ‘portrait of a city’ in relation to the Ponte City project, and asks the questions: What is a portrait of a city? Is it possible to take a ‘portrait of a city’, and what techniques are used when a photographer portrays places and people, or attempts to take, or make, a ‘portrait’ – of a city, a place or even a building such as Ponte? Can a building come to stand in for a city? And how have these -

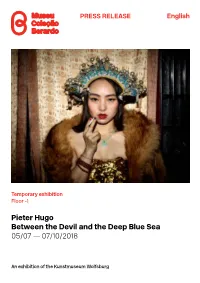

Pieter Hugo Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea 05/07 — 07/10/2018

PRESS RELEASE English Temporary exhibition Floor -1 Pieter Hugo Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea 05/07 — 07/10/2018 An exhibition of the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg PIETER HUGO 1994 BETWEEN THE DEVIL AND THE DEEP BLUE SEA Rwanda & South Africa 2014–2016 After the first comprehensive presentation consisting of fifteen series, produced between 2003 and 2016, at 1994 was a significant year for me. I finished school and the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, the show was presented left home. Nelson Mandela was elected president in at Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, in Dortmund, South Africa’s first democratic election, after decades of and has now found its third venue at Museu Coleção apartheid. Berardo, in Lisbon. It was also the year of the Rwandan genocide, an event What divides us and what unites us? How do people which shook me. Ten years later I was to photograph its live with the shadows of cultural repression or political aftermath extensively, and puzzle over its legacy. dominance? The South African photographer Pieter Hugo When I returned to Rwanda on assignment in 2014, (b. 1976, Johannesburg) explores these questions in his my own children were one and four years old. They portraits, still-lifes, and landscapes. had changed my way of looking at things. Whereas on Raised in post-colonial South Africa, where he witnessed previous visits to Rwanda I’d barely seen any children, this the official end of apartheid in 1994, Hugo has a keen time I noticed them everywhere. sense for social dissonances. He perceptively makes The Rwandan children raised the same questions in me as his way through all social classes with his camera, my own children.