Secular S`Eance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pieter Hugo. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue

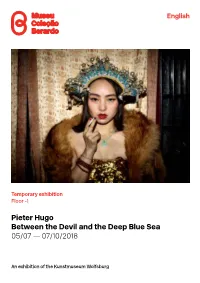

English Temporary exhibition Floor -1 Pieter Hugo Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea 05/07 — 07/10/2018 An exhibition of the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg PIETER HUGO 1994 BETWEEN THE DEVIL AND THE DEEP BLUE SEA Rwanda & South Africa 2014–2016 After the first comprehensive presentation consisting of fifteen series, produced between 2003 and 2016, at 1994 was a significant year for me. I finished school and the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, the show was presented left home. Nelson Mandela was elected president in at Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, in Dortmund, South Africa’s first democratic election, after decades of and has now found its third venue at Museu Coleção apartheid. Berardo, in Lisbon. It was also the year of the Rwandan genocide, an event What divides us and what unites us? How do people which shook me. Ten years later I was to photograph its live with the shadows of cultural repression or political aftermath extensively, and puzzle over its legacy. dominance? The South African photographer Pieter Hugo When I returned to Rwanda on assignment in 2014, (b. 1976, Johannesburg) explores these questions in his my own children were one and four years old. They portraits, still-lifes, and landscapes. had changed my way of looking at things. Whereas on Raised in post-colonial South Africa, where he witnessed previous visits to Rwanda I’d barely seen any children, this the official end of apartheid in 1994, Hugo has a keen time I noticed them everywhere. sense for social dissonances. He perceptively makes The Rwandan children raised the same questions in me as his way through all social classes with his camera, my own children. -

Art at the Silo Hotel a Brief History

ART AT THE SILO HOTEL A BRIEF HISTORY The history of Africa is the history of being plundered for its most valuable resources. This was exemplified by the original grain silo building in Table Bay from which grain was exported to Europe. The new building represents a showcase retaining Africa’s greatest creative resources. The building itself can be seen as a work of art, offering it’s beautifully reimagined structure as an industrial canvas that highlights the very best of African art and design. “I have always included wonderful art at each of The Royal Portfolio properties. Art brings a space Liz Biden, owner of The Royal Portfolio pays tribute to this vision, through her use of to life, it creates warmth and tells stories. But moreover, art takes you on a journey which evolves contemporary African art and local craftsmanship in her interior design of The Silo as we evolve. Our guests love to enjoy the art collection at our properties. The Silo Hotel will take Hotel. that art experience to a whole new level with a focus on contemporary African art…” LIZ BIDEN During her trips throughout Africa, aided by her well-travelled eye for the exquisite FOUNDER AND OWNER and the unusual, Liz Biden has acquired a unique and varied collection of art that complements that of Zeitz MOCAA situated below The Silo Hotel. Highlighting both young, aspiring artists, as well as established, highly acclaimed artists such as Cyrus Kabiru, Mahau Modisakeng and Nandipha Mntambo. Liz Biden has specifically chosen pieces to complement the unique interiors of each of the 28 rooms, offering individualised experiences for guests and many a reason to return. -

PERSPECTIVES 2 5 March – 11 April 2015

PERSPECTIVES 2 5 MARch – 11 APRIL 2015 Perspectives 2 Perspectives 2 – as its title suggests, the second in a His Presence, a painting first shown in the Zimbabwean series of group exhibitions titled Perspectives – features Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale (2013). Moshekwa works by Walter Battiss, Zander Blom, David Goldblatt, Langa’s trance-like paintings similarly imagine a realm Pieter Hugo, Anton Kannemeyer, Moshekwa Langa, beyond comprehension, and the sparse black gestures Stanley Pinker, Robin Rhode, Penny Siopis of Zander Blom’s Untitled [1.288] draw inspiration from and Portia Zvavahera. the mark-making of South African modernist Ernest Mancoba’s lifelong meditation on the essence Many of the works included in Perspectives 2 have been of human form. exhibited in the gallery over the past 12 years; others by gallery artists were exhibited further afield. They return to A group of works picture scenes of pleasure. Stanley be offered to new collectors to start new conversations, and Pinker’s The Bather is a small, joyous painting of a nude from this group several themes emerge. sitting alongside a lake, and is a portrait of intimacy and relaxation calmingly rendered in a spring palette. Battiss’ The notion of seriality is prominent. Walter Battiss’ colourful renderings of women from the Bajun Islands watercolours painted at Leisure Bay in KwaZulu-Natal are on the Kenyan coast, and his watercolours of Leisure studies of colour and light at different times of the day. Bay, his holiday destination, offer comparably hedonistic Zander Blom’s large-scale abstract painting Untitled [1.300] sensibilities. This motif extends to the primary-coloured offers repetition in mark-making and so allows the viewer’s nude gathering in Battiss’ sgraffito oil on canvas Figures eye to circulate through it. -

African Afro-Futurism: Allegories and Speculations

African Afro-futurism: Allegories and Speculations Gavin Steingo Introduction In his seminal text, More Brilliant Than The Sun, Kodwo Eshun remarks upon a general tension within contemporary African-American music: a tension between the “Soulful” and the “Postsoul.”1 While acknowledging that the two terms are always simultaneously at play, Eshun ultimately comes down strongly in favor of the latter. I quote him at length: Like Brussels sprouts, humanism is good for you, nourishing, nurturing, soulwarming—and from Phyllis Wheatley to R. Kelly, present-day R&B is a perpetual fight for human status, a yearning for human rights, a struggle for inclusion within the human species. Allergic to cybersonic if not to sonic technology, mainstream American media—in its drive to banish alienation, and to recover a sense of the whole human being through belief systems that talk to the “real you”—compulsively deletes any intimation of an AfroDiasporic futurism, of a “webbed network” of computerhythms, machine mythology and conceptechnics which routes, reroutes and criss- crosses the Atlantic. This digital diaspora connecting the UK to the US, the Caribbean to Europe to Africa, is in Paul Gilroy’s definition a “rhizo- morphic, fractal structure,” a “transcultural, international formation.” […] [By contrast] [t]he music of Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra, of Underground Resistance and George Russell, of Tricky and Martina, comes from the Outer Side. It alienates itself from the human; it arrives from the future. Alien Music is a synthetic recombinator, an applied art technology for amplifying the rates of becoming alien. Optimize the ratios of excentric- ity. Synthesize yourself. -

A Decolonial Reading of Psalm 137 in Light of South Africa's Struggle Songs

464 Ramantswana, “Reading of Psalm 137,” OTE 32/2 (2019): 464-490 Song(s) of Struggle: A Decolonial Reading of Psalm 137 in Light of South Africa’s Struggle Songs HULISANI RAMANTSWANA (UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA) ABSTRACT This article engages in a decolonial reading of Ps 137 in light of South African songs of struggle. In this reading, Ps 137 is regarded as an epic song which combines struggle songs which originated within the golah community in response to the colonial relations between the oppressor and the oppressed. The songs of struggle then gained new life during the post-exilic period as a result of the new colonial relation between the Yehud community and the Persian Empire. Therefore, Ps 137 should be viewed as not a mere song, but an anthology of songs of struggle: a protest song (vv. 1-4), a sorrow song (vv. 5-6), and a war song (vv. 7- 9). KEYWORDS: Psalm 137, Songs of Struggle, protest song, sorrow song, war song, exile, Babylon, post-exilic, Persian Empire. A INTRODUCTION Bob Becking, in a paper entitled “Does Exile Equal Suffering? A Fresh Look at Psalm 137,”1 argues that exile and diaspora for the exiles who were in Babylon did not so much amount to things such as hunger and oppression or economic hardship; instead, it was more a feeling of alienation which resulted in the longing to return to Zion. Becking’s interpretation of Ps 137 tends to minimise the colonial dynamics involved in the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed, the coloniser and the colonised, which continually pushes the oppressed into the zone of nonbeing. -

Best of 2012

http://www.afropop.org/wp/6228/stocking-stuffers-2012/ Best of 2012 Ases Falsos - Juventud Americana Xoél López - Atlantico Temperance League - Temperance League Dirty Projectors - Swing Lo Magellan Protistas - Las Cruces David Byrne & St Vincent - Love This Giant Los Punsetes - Una montaña es una montaña Patterson Hood - Heat Lightning Rumbles in the Distance Debo Band - Debo Band Ulises Hadjis - Cosas Perdidas Dr. John - Locked Down Ondatrópica - Ondatrópica Cat Power - Sun Love of Lesbian - La noche eterna. Los días no vividos Café Tacvba - El objeto antes llamado disco Chuck Prophet - Temple Beautiful Hello Seahorse! - Arunima Campo - Campo Tame Impala - Lonerism Juan Cirerol - Haciendo Leña Mokoomba - Rising Tide Lee Fields & The Expressions - Faithful Man Leon Larregui - Solstis Father John Misty - Fear Fun http://www.bestillplease.com/ There’s still plenty of time to hit the open road for a good summer road trip. Put your shades on, roll down the windows, crank up the tunes and start cruising. Here are some of CBC World's top grooves for the summer of 2012. These are songs that have a real rhythm and a sunny, happy, high-energy vibe to them. 6. Mokoomba, “Njoka.” Mokoomba is a band from the Victoria Falls area of Zimbabwe, made up of musicians from the Tonga people of Zimbabwe. The textures on this first single, from Mokoomba's second album Rising Tide, are great, especially the vocals http://music.cbc.ca/#/blogs/2012/8/Road-trip-playlist-with-Quantic-the-Very-Best-Refugee-All-Stars-more CHARTS & LISTS AFRICAN MUSIC: THE BEST OF 2012. This list considers only new, original studio recordings released this year. -

The Smoke That Calls: Insurgent Citizenship, Collective Violence and the Struggle for a Place in the New South Africa

CSVR Final Cover 7/6/11 1:36 PM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The smoke that calls Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and th violence citizenship, collective Insurgent Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. in the new a place for and the struggle violence citizenship, collective Insurgent Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. The smoke that calls that calls The smoke The smoke Eight case studies of community protest and xenophobic violence www.csvr.org.za www.swopinstitute.org.za Karl von Holdt, Malose Langa, Sepetla Molapo, Nomfundo Mogapi, Kindiza Ngubeni, Jacob Dlamini and Adele Kirsten Composite CSVR Final Cover 7/7/11 9:51 AM Page 2 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Published: July 2011 Copyright 2011 ® Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation | Society, Work and Development Institute The smoke that calls: Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. Eight case studies of community protest and xenophobic violence Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Society, Work and Development Institute 4th Floor, Braamfontein Centre, 23 Jorissen Street, Braamfontein Faculty of Humanities PO Box 30778, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, 2017 University of the Witwatersrand Tel: +27 (0) 11 403 5650 | Fax: +27 (0) 11 339 6785 Private Bag 3, Wits, 2050 Cape Town Office Tel: +27 (0) 11 717 4460 501 Premier Centre, 451 Main Road, Observatory, 7925 Tel: +27 (0) 21 447 3661 | Fax: +27 (0) 21 447 5356 email: [email protected] www.csvr.org.za www.swopinstitute.org.za Composite CSVR - Chapter 1 - 5 7/6/11 1:52 PM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The smoke that calls Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. -

Live Music Audiences Johannesburg (Gauteng) South Africa

Live Music Audiences Johannesburg (Gauteng) South Africa 1 Live Music and Audience Development The role and practice of arts marketing has evolved over the last decade from being regarded as subsidiary to a vital function of any arts and cultural organisation. Many organisations have now placed the audience at the heart of their operation, becoming artistically-led, but audience-focused. Artistically-led, audience-focused organisations segment their audiences into target groups by their needs, motivations and attitudes, rather than purely their physical and demographic attributes. Finally, they adapt the audience experience and marketing approach for each target groupi. Within the arts marketing profession and wider arts and culture sector, a new Anglo-American led field has emerged, called audience development. While the definition of audience development may differ among academics, it’s essentially about: understanding your audiences through research; becoming more audience-focused (or customer-centred); and seeking new audiences through short and long-term strategies. This report investigates what importance South Africa places on arts marketing and audiences as well as their current understanding of, and appetite for, audience development. It also acts as a roadmap, signposting you to how the different aspects of the research can be used by arts and cultural organisations to understand and grow their audiences. While audience development is the central focus of this study, it has been located within the live music scene in Johannesburg and wider Gauteng. Emphasis is also placed on young audiences as they represent a large existing, and important potential, audience for the live music and wider arts sector. -

Songs and the Liberation Struggle in South Africa

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 27 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2014 Voices of Liberation: Songs and the Liberation Struggle in South Africa Rachidi Molapo University of Venda, RSA [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p985 Abstract Many communities around the world have taken part in songs and dance or have witnessed roles played by songs. However, scholarly focus on such a field of study has been very limited. This study challenges for a new consideration of what songs are and the roles they play or played in contemporary society. Songs have been means of communication, education and importantly played important roles in the struggle against apartheid. When the apartheid regime became repressive by banning or exiling leaders, suppressing information, songs in vernacular or indigenous languages flourished in promoting resistance texts. These songs flourished like graffities in repressive environments. They were used as propaganda tools by the liberation movements and at the same time dealing with state propaganda. They were platforms of propaganda in a dialectical relationship with the state but also embodied other elements beyond these parameters. Songs have been fundamental instruments of resistance, heritage and history. This study looks at how South African activists used songs and the struggle against apartheid and the post-apartheid scenario. Focus will be on the pre-1960 period, exile and the post- apartheid dynamics. A qualitative research methodology has been useful for this study because of the human agency aspect. Keywords: Apartheid (racial discrimination), Nkosi sikelel’ i-Africa (Lord bless Africa), siyanqonqoza (knocking) umshini wami, ibhunu (white farmer), dubula (shoot), exile. -

Polokwane Conference

No. 87 January 2008 POLOKWANE CONFERENCE- Searchlight on Highlights 1. The Rowdiness at the Conference 2. “My Comrade, my brother….my Leader.” 3. Purge in the National Executive Committee 4./…. 1 4. Dr Dube and Zuma 5. “Umshini Wami” 6. Large number of Votes for the NEC does not always mean Power 7. Newly elected NEC gives Pride of Place to Fraudsters and Thieves 8. A Plague on both their Houses APDUSA VIEWS e.mail: [email protected] P.O. Box 8888 website: www.apdusaviews .co.za CUMBERWOOD 3235 2 1. The Rowdiness Toward Senior ANC members The rowdiness exhibited by a large section of the ANC conference towards Minister Lekota was a measure of the hostility the Zuma supporters showed towards the Mbeki faction symbolised by Lekota as its chief spokesman in the battle against the Zuma faction. According to Mbeki, the image that behaviour “conveyed to the country, the continent and the world was a bad image.”1 In his closing speech, Zuma described the behaviour as “a negative”. According to Mbeki: “The matter was addressed and delegates were told that their behaviour was unacceptable and indeed the behaviour improved.”2 Those of us viewing these “disturbing” scenes on television would have noticed that that behaviour was being exhibited in the very presence of Jacob Zuma. The question on everybody lips is: Why did Jacob Zuma not get up from his seated position and direct/instruct /request his supporters to stop behaving in that unacceptable manner? There appears to be only one answer: It was orchestrated rowdiness which had the full approval of Jacob Zuma! Postscript. -

Native Foreigners’

From ‘Foreign Natives’ to ‘Native Foreigners’ Contents, Neocosmos2.pmd 1 29/04/2010, 17:26 Contents, Neocosmos2.pmd 2 29/04/2010, 17:26 From ‘Foreign Natives’ to ‘Native Foreigners’ Explaining Xenophobia in Post-apartheid South Africa Citizenship and Nationalism, Identity and Politics Michael Neocosmos Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Contents, Neocosmos2.pmd 3 29/04/2010, 17:26 First published under the CODESRIA Monograph Series, 2006 © CODESRIA 2010 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV BP 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. ISBN: 978-2-86978-307-2 Layout: Hadijatou Sy Cover Design: Ibrahima Fofana Printed by: Graphi plus, Dakar, Senegal Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by the African Books Collective, Oxford, UK. Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums geared towards the exchange of views and information among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes a quarterly journal, Africa Development, the longest standing Africabased social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; the African Journal of International Affairs; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................