IOB Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Clusters in Plants. Fast Channel Plant Communications. Planet Influence

Vol.1, No.1, 1-11 (2010) Journal of Biophysical Chemistry doi:10.4236/jbpc.2010.11001 Water clusters in plants. Fast channel plant communications. Planet influence Kristina Zubow1, Anatolij Viktorovich Zubow2, Viktor Anatolijevich Zubow1* 1“Aist Handels- und consulting GmbH”, R&D Department, Groß Gievitz, Germany; *Corresponding Author: [email protected] 2Department of Computer Science, Humboldt University Berlin, Berlin, Germany; [email protected] Received 19 April, 2010; revised 30 April, 2010; accepted 7 May 2010. ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION In tubers of two potato cultivars and in one ap- It is well known, that in the bulk water molecules form ple cultivar, water clusters, consisting of 11 ± 1, clusters [1]. Though clusters were discovered in bio- 100, 178, 280, 402, 545, 715, 903, 119, 1351, 1606 logical matrices [2] until now there isn’t still a method and 1889 molecules, were directly (in-vivo) by which clusters in plants can be identified during analyzed by gravitation spectroscopy. The growth in-vivo. By Okonchi Shoichi [3] it was suggested, clusters’ interactions with their surroundings that water molecules are in the form of clusters in living during plant growth in summer 2006 in Germany organisms. In Figure 1 computer models of some water were described where a model represents the clusters are given. In our laboratory, we developed a states of water clusters in bio matrices. Fur- gravitation spectrometer for water cluster identification thermore, a comparison with clusters in irriga- in bio-matrices of plants [4-6]. Knowing the state of tion water (river, rain) is given. To achieve a high water clusters in plants could be helpful for understand- and good quality yield it is necessary to choose ing the relation between biochemical processes at nano- the right irrigation water that has to correspond scale level during growth and qualitative yields. -

Water Cluster Ensembles As Interface to the Structure of Epicenter and the Earthquake Mechanism on the Jawa Island ´ S

id4277265 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ISSN : 0974 - 7524 Volume 7 Issue 3 Physical CCHHEEAMMn InIIdSSiaTnT JRoRurYnYal Trade Science Inc. Full Paper PCAIJ, 7(3), 2012 [87-95] Water cluster ensembles as interface to the structure of epicenter and the earthquake mechanism on the Jawa island ´ s. 112 ´ e.) (8 73 36 K.Zubow2, A.Zubow1, V.A.Zubow2* 1Dept.of Computer Science, Humboldt University Berlin, Johann von Neumann Haus, House III, 3rd Floor, Rudower Chaussee 25, D-12489 (BERLIN) 2«A IST H&C», Dept.R&D, D-17192 Groß Gievitz, Dorfstraße, 3, (GERMANY) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 6th December, 2011 ; Accepted: 7th January, 2012 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The long-range order (LRO) in underground water (North Germany) that Water; was excited by gravitation was investigated in the period of August 13th to Clusters; 14th, 2009. The average molecular mass of water clusters, the forms of the Epicenter; Structure; base water cluster (H2O)12 and of the Chaplin cluster (H2O)280, were found to correlate with a series of gravitation excitation which is connected with Earthquake; the earthquake on the Java island. It has been investigated how earth- Mechanism; quakes at distance influence the general energy capacity of the water Jawa. cluster ensembles. A mechanism describing generation and development of gravitation tensions in the epicenter on Java as the result of changed hydrogen bridges in water under the influence of impulse pressure up to 0.46 GPa has been suggested. -

BEYOND the STATUS QUO: 2015 EQB Water Policy Report

BEYOND THE STATUS QUO: 2015 EQB Water Policy Report LAKE ST. CROIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 4 Health Equity and Water. 5 GOAL #1: Manage Water Resources to Meet Increasing Demands . .6 GOAL #2: Manage Our Built Environment to Protect Water . 14 GOAL #3: Increase and Maintain Living Cover Across Watersheds .. 20 GOAL #4: Ensure We Are Resilient to Extreme Rainfall . .28 Legislative Charge The Environmental Quality Board is mandated to produce a five year water Contaminants of Emerging Concern . .34 policy report pursuant to Minnesota Statutes, sections 103A .204 and 103A .43 . Minnesota’s Water Technology Industry . 36 This report was prepared by the Environmental Quality Board with the Board More Information . .43 of Water and Soil Resources, Department of Agriculture, Department of Employment and Economic Development, Department of Health, Department Appendices available online: of Natural Resources, Department of Transportation, Metropolitan Council, • 2015 Groundwater Monitoring Status Report and Pollution Control Agency . • Five-Year Assessment of Water Quality Degradation Trends and Prevention Efforts Edited by Mary Hoff • Minnesota’s Water Industry Economic Profile Graphic Design by Paula Bohte • The Agricultural BMP Handbook for Minnesota The total cost of preparing this report was $76,000 • Water Availability Assessment Report 2 Beyond the Status Quo: 2015 EQB Water Policy Report Minnesota is home to more than 10,000 lakes, 100,000 miles of rivers and streams, and abundant groundwater resources. However, many of these waters are not clean enough. In 2015, we took a major step toward improving our water by enacting a law that protects water quality by requiring buffers on more than 100,000 acres of land adjacent to water. -

Local Identities

Local Identities Editorial board: Prof. dr. E.M. Moormann Prof. dr.W.Roebroeks Prof. dr. N. Roymans Prof. dr. F.Theuws Other titles in the series: N. Roymans (ed.) From the Sword to the Plough Three Studies on the Earliest Romanisation of Northern Gaul ISBN 90 5356 237 0 T. Derks Gods,Temples and Ritual Practices The Transformation of Religious Ideas and Values in Roman Gaul ISBN 90 5356 254 0 A.Verhoeven Middeleeuws gebruiksaardewerk in Nederland (8e – 13e eeuw) ISBN 90 5356 267 2 N. Roymans / F.Theuws (eds) Land and Ancestors Cultural Dynamics in the Urnfield Period and the Middle Ages in the Southern Netherlands ISBN 90 5356 278 8 J. Bazelmans By Weapons made Worthy Lords, Retainers and Their Relationship in Beowulf ISBN 90 5356 325 3 R. Corbey / W.Roebroeks (eds) Studying Human Origins Disciplinary History and Epistemology ISBN 90 5356 464 0 M. Diepeveen-Jansen People, Ideas and Goods New Perspectives on ‘Celtic barbarians’ in Western and Central Europe (500-250 BC) ISBN 90 5356 481 0 G. J. van Wijngaarden Use and Appreciation of Mycenean Pottery in the Levant, Cyprus and Italy (ca. 1600-1200 BC) The Significance of Context ISBN 90 5356 482 9 Local Identities - - This publication was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). This book meets the requirements of ISO 9706: 1994, Information and documentation – Paper for documents – Requirements for permanence. English corrected by Annette Visser,Wellington, New Zealand Cover illustration: Reconstructed Iron Age farmhouse, Prehistorisch -

BARBABRABANT Collaboration As Foundation for a Robust Hydrological Future

BARBABRABANT Collaboration as foundation for a robust hydrological future. Marieke van den Broek (960130128100), Tim den Duijf (951207205130), Henk Jan Lekkerkerk (970501510030), Esther van der Meer (951108551120), Josselin Snoek (940310782060), Rianne Wassink (990422930120) Commissioner: Rob Brinkhof, municipality Den Bosch LUP-60309 (Atelier) INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM STATEMENT Figure 1: a selection from the stream of articles about drought (Volkskrant, 2020) Figure 2: a selection from the stream of articles about drought (Volkskrant, 2020) Water management plan reality. This upscaling was a general plan, less focussed Currently water boards are responsible for maintaining droughts in the summer. The Netherlands is a country of water. Due to its position on local differences, both in land use and hydrological ground water levels for agricultural systems in place and The city of Den Bosch, in the south of the Netherlands, is in the delta of several international rivers, the Netherlands systems. Nevertheless, it was not without success, since the the (artificial) hydrological system follows the land use a place where the urgency is already tangible. The city is has always known the need to relate to water. We use it to Netherlands is now one of the largest agricultural exporters (Geelen, 2020), but this is not enough to solve structural built on a sand ridge in the middle of the delta of the rivers travel, trade and protect ourselves. This position in the delta in the world (M. Kuijpers, personal communication, June droughts. Dommel and Aa, which run off in the Maas on the north also urges the need to defend ourselves against the water. -

Environmental Science Nano Accepted Manuscript

Environmental Science Nano Accepted Manuscript This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication. Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. We will replace this Accepted Manuscript with the edited and formatted Advance Article as soon as it is available. You can find more information about Accepted Manuscripts in the Information for Authors. Please note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the text and/or graphics, which may alter content. The journal’s standard Terms & Conditions and the Ethical guidelines still apply. In no event shall the Royal Society of Chemistry be held responsible for any errors or omissions in this Accepted Manuscript or any consequences arising from the use of any information it contains. rsc.li/es-nano Page 1 of 23 Environmental Science: Nano Nano Impact Statement Site specific risk assessment of engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) requires spatially resolved fate models. Validation of such models is difficult, due to present limitations in detecting ENPs in the environment. Here we report on progress towards validation of the spatially resolved hydrological ENP fate model NanoDUFLOW, by comparing measured and modeled concentrations of < 450 nm metal-based particles in a river. Concentrations measured with Asymmetric Flow-Field-Flow Fractionation (AF4) coupled to ICP-MS, clearly reflected the hydrodynamics of the river and showed satisfactory to good agreement with modeled concentration profiles. -

De Kroniek Van Het St. Geertruiklooster Te 'S-Hertogenbosch Een Tekstuitgave

De kroniek van het St. Geertruiklooster te ’s-Hertogenbosch Die chronijcke der Stadt ende Meijerije van ‘s-Hertogenbosch Een tekstuitgave door H. van Bavel o. praem. dr. A.C.M. Kappelhof G.M. van der Velden o. praem. drs. G. Verbeek © Stadsarchief ‘s-Hertogenbosch/Abdij van Berne Heeswijk 2001 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave . iii Inleiding . iv Verantwoording van de uitgave . v Levensloop van de kroniek . vi Plaatsbepaling en typering . vii Profiel van de schrijver van de kroniek. viii Gebruikswaarde van de kroniek . x De kroniek, deel 1 . 1 1140 - 1199. 3 1200 - 1249. 7 1250 - 1299. 9 1300 - 1349. 13 1350 - 1399. 21 1400 - 1449. 32 1450 - 1474. 42 1475 - 1499. 50 1500 - 1512 . 62 1513 - 1524 . 74 1525 - 1537. 98 1538 - 1549. 123 1550 - 1567. 156 1568 - 1570. 186 1571 . 201 1572 - 1574. 217 1575 - 1577. 224 1578 . 236 1579 . 242 1580 - 1584. 256 1585 - 1595. 266 De kroniek, deel 2 . 279 1595 - 1599. 281 1600 - 1604. 285 1605 - 1624. 307 1625 - 1628. 326 1629 . 329 1630 - 1649. 364 1650 - 1674. 374 1675 - 1699. 391 iii Inleiding In 1977 brachten de toenmalige gemeentearchivaris van ’s-Hertogenbosch, drs. P.Th.J. Kuyer, en zijn rechterhand, mr. J. Hoekx, een bezoek aan de bibliotheek van de abdij van Berne te Heeswijk. De archivaris van de abdij, H. van Bavel, toonde hun een oud, anoniem handschrift met daarin een kroniek van de stad ‘s-Hertogenbosch. De titel ervan luidde: “Die chronijcke der Stadt ende Meijerije van ‘s-Hertogenbosch”. Na enig onderzoek concludeerden de drie heren dat het hier om een nagenoeg vergeten, maar wel belangrijke kroniek ging die verder onderzoek en een uitgave verdiende. -

2Nd Annual Report Cluster Topic Water and Water Resources

2nd Annual Report Cluster Topic Water and Water Resources Submitted by Akanda, A., Amador, J., Boving, T.*, Craver, V., Guilfoos, T., Johnson, K., Lohmann, R., Opaluch, J. * Contact: Tom Boving ([email protected]) May 31, 2014 A. Background Life on Earth depends on water and there is simply no substitute for it. Yet, humanity has degraded or depleted many sources of water and is now confronted with a severe water crisis that already affects large parts of the World. Humanity's response to the water crisis requires that scientists, engineers, economist and policy makers to work together and develop effective and sustainable strategies for managing this essential natural resource. For the foreseeable future, it is of vital importance to strive for an understanding of the compleX connections between the various compartments of the environment that influence the availability and quality of water on local and global scales. In an area that is critical to the Rhode Island and the world, and equally important, to student learning and future employment, the study of water enhances the magnitude and impact of learning and discovery at the University of Rhode Island. Consequently, URI decided to invest into a cluster of three new faculty positions that strategically address the most pressing issues of the 21st century: Safe, Sustainable, and Secure Water. The following provides an overview of the activities that completed the hiring process of three new water cluster faculty members. It also provides a perspective on the activities of the water cluster faculty during the Academic Year 2013/14. B. Summary of Activities The “Water Cluster” is a university wide initiative in which four Colleges (CELS, COE, A&S and GSO) and ten departments (BIO, CHE, CHM, CVE, GEO, LAR, NRS, PSC, PLS, and WRT) and several eXtension and outreach programs proposed to hire three new faculty members. -

![Arxiv:2012.00131V1 [Cs.LG] 30 Nov 2020 Long-Range Interactions [10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5144/arxiv-2012-00131v1-cs-lg-30-nov-2020-long-range-interactions-10-1195144.webp)

Arxiv:2012.00131V1 [Cs.LG] 30 Nov 2020 Long-Range Interactions [10]

HydroNet: Benchmark Tasks for Preserving Intermolecular Interactions and Structural Motifs in Predictive and Generative Models for Molecular Data Sutanay Choudhury Jenna A. Bilbrey Logan Ward [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sotiris S. Xantheas Ian Foster Joseph P. Heindel [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ben Blaiszik Marcus E. Schwarting [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Intermolecular and long-range interactions are central to phenomena as diverse as gene regulation, topological states of quantum materials, electrolyte transport in batteries, and the universal solvation properties of water. We present a set of challenge problems 1 for preserving intermolecular interactions and structural motifs in machine-learning approaches to chemical problems, through the use of a recently published dataset of 4.95 million water clusters held together by hydrogen bonding interactions and resulting in longer range structural patterns. The dataset provides spatial coordinates as well as two types of graph representations, to accommodate a variety of machine-learning practices. 1 Introduction The application of machine-learning (ML) techniques such as supervised learning and generative models in chemistry is an active research area. ML-driven prediction of chemical properties and generation of molecular structures with tailored properties have emerged as attractive alternatives to expensive computational methods [20, 24, 23, 32, 31, 7, 14, 16, 22]. Though increasingly used, graph representations of molecules often do not explicitly include non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, which poses difficulties when examining systems with intermolecular and/or arXiv:2012.00131v1 [cs.LG] 30 Nov 2020 long-range interactions [10]. -

Oude Boskernen in Midden- En Oost-Brabant

Oude Boskernen in Midden- en Oost-Brabant autochtone bomen en struiken in vier reconstructiegebieden Ecologisch Adviesbureau Van Loon Ecologisch Adviesbureau Maes in opdracht van de Brabantse Milieu Federatie, Tilburg Januari 2008 Oude Boskernen in Midden- en Oost-Brabant autochtone bomen en struiken in vier reconstructiegebieden: · De Meierij · Beerze-Reusel · Boven-Dommel · De Peel Ecologisch Adviesbureau Van Loon Ecologisch Adviesbureau Maes in opdracht van de Brabantse Milieu Federatie, Tilburg Januari 2008 Colofon Tekst Bert Maes: redactie René van Loon Foto’s Bert Maes en René van Loon Lay out Emma van den Dool (EAM) Veldonderzoek René van Loon, Bert Maes mmv van Guido de Bont (EAM) en Henk Kuiper (EAM) Begeleiding Ben van Dinther, Marianne Gloudemans en Jan van Rijen (BMF) Opdracht Brabantse Milieufederatie Financiering Provincie Noord-Brabant Oude Boskernen in Midden- en Oost-Brabant Inhoudsopgave Hfdst:: 1 Inleiding 3 2 Werkwijze 5 3 Het belang van autochtone bomen en struiken 13 4 De provincie Noord-Brabant als een bron voor autochto- 16 ne bomen en struiken 5 De resultaten van het onderzoek 18 5.1 de reconstructiegebieden 5.2 landbouwontwikkelingsgebieden 5.3 het Beerzedal: robuuste ecologische verbindingszo- ne 5.4 grootstedelijke ontwikkelingsgebieden 6 Oogst- en kweekprogramma 38 7 Conclusies en aanbevelingen 41 8 Literatuur 44 Bijlage 1: Lijst van oudbossoorten in Nederland Bijlage 2: Ontwerp Naamlijst van inheemse boom- en struiksoorten waarvan autochtone exemplaren voorkomen in Nederland Bijlage 3: Overzicht oogst- en kweekprogramma Op afzonderlijke cd-rom: Bijlage 4: Overzicht resultaten van de inventarisatie (verkort, per soort) Bijlage 5: Overzicht van de volledige opnamen van de inventarisatie Bijlage 6: Kaarten overzicht ligging oude boskernen en houtwallen 1 Oude Boskernen in Midden- en Oost-Brabant 2 Oude Boskernen in Midden- en Oost-Brabant 1. -

Ionization Dynamics of the Branched Water Cluster: a Long-Lived Non-Proton-Transferred Intermediate

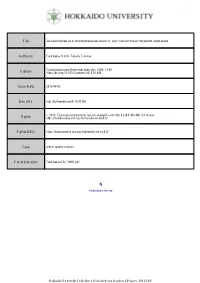

Title Ionization dynamics of the branched water cluster: A long-lived non-proton-transferred intermediate Author(s) Tachikawa, Hiroto; Takada, Tomoya Computational and theoretical chemistry, 1089, 13-20 Citation https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2016.05.008 Issue Date 2016-08-02 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/71126 © 2016. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license Rights http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Rights(URL) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Type article (author version) File Information Tachikawa-CTC(1089).pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Ionization Dynamics of the Branched Water Cluster: A Long-lived Non-Proton-transferred Intermediate Hiroto TACHIKAWA*a and Tomoya TAKADAb aDivision of Materials Chemistry, Graduate School of Engineering, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-8628, Japan bDepartment of Bio- and Material photonics, Chitose Institute of Science and Technology, Bibi, Chitose 066-8655, Japan Manuscript submitted to: Computational and Theoretical Chemistry Section of the journal: Article Running title: Reaction rate of proton transfer Correspondence and Proof to: Dr. Hiroto TACHIKAWA* Division of Materials Chemistry Graduate School of Engineering Hokkaido University Sapporo 060-8628, JAPAN [email protected] Fax +81 11706-7897 Contents: Text 15 Pages Figure captions 1 Page Table 1 Figures 7 Graphical Abstract 1 Highlights 1 Ionization Dynamics of the Branched Water Cluster: A Long-lived Non-Proton-transferred Intermediate Authors: Hiroto TACHIKAWA*a and Tomoya TAKADAb aDivision of Materials Chemistry, Graduate School of Engineering, Hokkaido University, Kita-ku, Sapporo 060-8628, Japan bDepartment of Bio- and Material photonics, Chitose Institute of Science and Technology, Bibi, Chitose 066-8655, Japan Abstract: The proton transfer (PT) reaction after water cluster ionization is known to be a very fast process occurring on the 10-30 fs time scale. -

Landschapsvisie Beneden Dommel, Het Dommeldal Tussen Son En Boxtel

LANDSCHAPSVISIE ONDERBOUWING VAN BENEDEN DOMMEL, HET DE INRICHTINGSPLANNEN DOMMELDAL TUSSEN EN DE NNB-HERBEGRENZING SON EN BOXTEL IN HET GROENE WOUD AUTEURS: IMKE NABBEN, NICO DE KONING, GER VAN DEN OETELAAR COLOFON Titel: Landschapsvisie Beneden Dommel, het Dommeldal tussen Son en Boxtel. Onderbouwing van de inrichtingsplannen en de NNB-herbegrenzing in Het Groene Woud Versie: definitief Auteurs: Imke Nabben, Nico de Koning, Ger van den Oetelaar, ARK Natuurontwikkeling Redactie: Jan van der Straaten Kaarten: Oolder (Victor Mattart) Foto’s: Bert Vervoort en Dirk Eijkemans Datum: 12 juni 2021 Uitgave: ARK Natuurontwikkeling, Nijmegen Contactadres: ARK Natuurontwikkeling Molenveldlaan 43 6523 RJ Nijmegen [email protected] T: 0620447518 www.ark.eu LANDSCHAPSVISIE ONDERBOUWING VAN BENEDEN DOMMEL, HET DE INRICHTINGSPLANNEN DOMMELDAL TUSSEN EN DE NNB-HERBEGRENZING SON EN BOXTEL IN HET GROENE WOUD AUTEURS: IMKE NABBEN, NICO DE KONING, GER VAN DEN OETELAAR Dwarsprofiel van een beek.1 ARK richt zich op het centrum van het beekdal waar het Natuurnetwerk Brabant gerealiseerd wordt. Om aanvullende doelen (bijvoorbeeld anti-verdroging of vermesting) te realiseren zijn ook maatregelen nodig buiten dit gebied. 1 Programma Lumbricus 4 Dommelgebied. d e D o m m e l GEMONDE SCHIJNDEL WIJBOSCH EERDE De Geelders BOXTEL OLLAND A50 LENNISHEUVEL d e D o m m e l LIEMPDE SINT-OEDENRODE d e D o m m e l A2 Dommelbeemden Vressels Bosch BOSKANT NIJNSEL Velderbos De Scheeken Wolfswinkel SON EN BREUGEL OIRSCHOT BEST 5 INHOUDSOPGAVE 4.5. Bedrijvigheid 82 4.6. Bevloeiingssysteem 82 DEEL I 9 4.7. Watermolens 84 4.8. Tussen Son en Sint-Oedenrode 84 1.