Civil Society Joint Alternative Follow-Up Report One Year After the UN Committee Against Torture’S Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Bengali: ; 17 শখ মুিজবুর রহমান Bangabandhu March 1920 – 15 August 1975), shortened as Sheikh Mujib or just Mujib, was a Bangladeshi politician and statesman. He is called the ববু "Father of the Nation" in Bangladesh. He served as the first Sheikh Mujibur Rahman President of Bangladesh and later as the Prime Minister of শখ মুিজবুর রহমান Bangladesh from 17 April 1971 until his assassination on 15 August 1975.[1] He is considered to be the driving force behind the independence of Bangladesh. He is popularly dubbed with the title of "Bangabandhu" (Bôngobondhu "Friend of Bengal") by the people of Bangladesh. He became a leading figure in and eventually the leader of the Awami League, founded in 1949 as an East Pakistan–based political party in Pakistan. Mujib is credited as an important figure in efforts to gain political autonomy for East Pakistan and later as the central figure behind the Bangladesh Liberation Movement and the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. Thus, he is regarded "Jatir Janak" or "Jatir Pita" (Jatir Jônok or Jatir Pita, both meaning "Father of the Nation") of Bangladesh. His daughter Sheikh Hasina is the current leader of the Awami League and also the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. An initial advocate of democracy and socialism, Mujib rose to the ranks of the Awami League and East Pakistani politics as a charismatic and forceful orator. He became popular for his opposition to the ethnic and institutional discrimination of Bengalis 1st President of Bangladesh in Pakistan, who comprised the majority of the state's population. -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 15, Issue 4

War Crimes Prosecution Watch Editor-in-Chief David Krawiec FREDERICK K. COX Volume 15 - Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER April 11, 2020 Technical Editor-in-Chief Erica Hudson Founder/Advisor Michael P. Scharf Managing Editors Matthew Casselberry Faculty Advisor Alexander Peters Jim Johnson War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents AFRICA NORTH AFRICA Libya Course of coronavirus pandemic across Libya, depends on silencing the guns (UN News) Libya government: ‘UAE drones targeted post office in Sirte’ (Middle East Monitor) CENTRAL AFRICA Central African Republic Sudan & South Sudan Democratic Republic of the Congo Convicted Congolese Warlord Escapes. Again. (Human Rights Watch) WEST AFRICA Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Lake Chad Region — Chad, Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon Mali Atrocity Alert No. 196: Yemen, South Sudan and Mali (reliefweb) Liberia Belgian investigators drag feet on Martina Johnson; Liberia’s War Criminal (Global News Network) George Dweh, Notorious Civil War Actor, Is Dead (Daily -

Modi's Great Gamble

EXCLUSIVE BANGLADESH FOREIGN MINISTER ADMITS... CRIME TECH-SAVVY TEENS YES, INDIA HELPED NAB MUJIB KILLER TERRORISE SCHOOLGIRLS ZOOM’S INDIA HEAD WARNING USERS AGAINST US WAS UNFORTUNATE EXCLUSIVE BEN STOKES: BAFFLED HOW VIRAT, ROHIT PLAYED AGAINST US MODI’S GREAT GAMBLE No free lunches in the biggest reforms PLUS CHIEF ECONOMIC ADVISER KRISHNAMURTHY SUBRAMANIAN OUT OF THE BOX IDEAS ON THE TABLE, TOO P. CHIDAMBARAM FORMER FINANCE MINISTER THIS GOVT IS OPPORTUNISTIC D. SUBBARAO, EX-RBI CHIEF CRISIS THE RIGHT TIME FOR REFORMS VOL. 38 NO. 22 THE WEEK MAY 31 2020 FOR THE WEEK MAY 25 - MAY 31 12 52 63 SALIL BERA SALIL GETTY IMAGES SPECIAL REPORT EXCLUSIVE @LEISURE India takes a big step in repairing ties In his new book, cricketer Ben Stokes With auditoriums and theatres with Bangladesh by helping it nab remembers his World Cup journey. closed, artistes are embracing Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s killers Plus: Excerpts from the book online platforms 18 CRIME 32 COVER STORY The Bois Locker COLUMNS Room case highlights 9 POWER POINT the need to give teeth Sachidananda Murthy to Indian cyberlaw 27 FORTHWRITE 22 GENE MUTATION Meenakshi Lekhi New variants of the novel coronavirus 46 DETOUR may hamper efforts Shobhaa De to create a vaccine 55 SOUND BITE Anita Pratap 28 KERALA The success of the 57 SCHIZO-NATION fight against Covid-19 Anuja Chauhan is also the success of women empow- 74 LAST WORD Shashi Tharoor CRISIS MANAGEMENT erment and welfare measure GETTY IMAGES Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman 50 BUSINESS till October: Prem Singh New users were using Tamang, Sikkim chief TOUGH LOVE Zoom in an unse- minister The government offers not cash, but a fighting chance. -

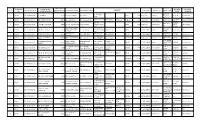

SL.NO WARRANT NO. FOLIO/ BO ID No NAME of the SHAREHOLDERS NET CASH DIVIDEND for the YEAR 2015 FATHER's NAME MOTHER's NAME COUNT

NET CASH WARRANT NAME OF THE BRANCH ACCOUNT SL.NO FOLIO/ BO ID No DIVIDEND FOR FATHER'S NAME MOTHER'S NAME ADDRESS COUNTRY PHONE NO BANK NAME NO. SHAREHOLDERS NAME NUMBER THE YEAR 2015 Standdard 43, Fakirapool 1 1500901 1201470000562060 QAIS HUDA 339.37 Late. Shamsul Huda Hossan Banu Dhaka 1000 Bangladesh 8350651 Chartered Banani Br. 01628693301 Bazar Bank Hoque Miner 412- Lake Avenue Chittagong 2 1500903 1201480018023311 MD. ARIFUL HOQUE 249.17 Late Sirajul Hoque Mrs. Tanjama Khatun Chittagong Chittagong 4100 Bangladesh 01915350550 HSBC Ltd. CA-004.170650011 A1, H/S, Pahartali, Branch 213, West Bonoshree Dhaka Bank 3 1500904 1201480048616428 TAHAMINA BEGUM 154.96 Late Md. Ataur Rahman Umme Kulshum Rampura Wapda Dhaka 1219 Bangladesh 01670279102 Branch, 227.200.2744 Ltd. Road Rampura 272, NORTH MD. TAMIZ UDDIN UTTARA 4 1500906 1201510005042281 MD. RUHUL AMIN 45.17 SUFIA BEGUM GORAN(SEPAHI 3RD FLOOR. DHAKA 1219 BANGLADESH 8250758 B.B. ROAD 10323 AHMED BANK BAG) MOHAMMAD HOUSE# 214, EASTERN 5 1500907 1201510038740532 JANNATUL FARDOUS 239.41 SARA KHATUN SHANTIBAGH DHAKA 1217 BANGLADESH 01726-094760 ANY BR. 1011010145334 HOSSAIN 1ST FLOOR, BANK LTD. SONTOSH KUMAR Late Debendra Kumar 18/5, Baghmara Mymensing Janata Bank 6 1500909 1201520043630319 2555.97 Raj Laxmi Das Mymensingh, 2230 Bangladesh 8124886 NRB Br. 407008867 DAS Das Bormon Kuthir, h Ltd. STANDARD MOHAMMAD NASIM ALHAJ SHAMS NURUN NAHAR H NO#2, APT ROAD NO # 55, 7 1500910 1201530002203601 1549.67 DHAKA 1209 BANGLADESH 9887639 CHARTERED BANANI 18-6629024-01 HAIDER UDDIN HAIDER HAIDER NO# 1/A GULSHAN # 2 BANK 145/A, STADIUM, M.A.ABDUL BARICK MOSAMMOD SONALI 8 1500912 1201530012393345 MD.ABDUL LATIF 29.50 BANGABANDU PALTAN, DHAKA 1000 BANGLADESH 01711115424 STADUM 33004216 MOLLA SAEEDA KHATUM BANK NATIONAL DHAKA MD. -

Tracking Conflict Worldwide

CRISISWATCH Tracking Conflict Worldwide CrisisWatch is our global conict tracker, a tool designed to help decision-makers prevent deadly violence by keeping them up-to-date with developments in over 80 conicts and crises, identifying trends and alerting them to risks of escalation and opportunities to advance peace. Learn more about CrisisWatch April 2020 Global Overview APRIL 2020 Trends for Last Month April 2020 Deteriorated Situations Central African Republic, Outlook for This Month May 2020 Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Lesotho, Conflict Risk Alerts India (non-Kashmir), Kashmir, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, South China Sea, Burundi, Sri Lanka, Yemen, Libya El Salvador, Yemen, Libya Resolution Opportunities Improved Situations Yemen None The latest edition of Crisis Group’s monthly conict tracker highlights deteriorations in April in twelve countries and conict situations. In South Sudan, political leaders’ failure to agree on local power-sharing jeopardised the unity government, while a truce with holdout rebel groups in the south broke down. Militant attacks and counter-insurgency operations inside Jammu and Kashmir sharply intensied, and hate speech falsely accusing Muslims in India of propagating COVID-19 fuelled intercommunal attacks. In Myanmar, deadly ghting between the Arakan Army and the military continued at a high tempo in Rakhine and Shan States. A sudden spike in the number of homicides in El Salvador reversed months of improving security. Looking ahead to May, we warn of worsening situations in four countries. A deadly escalation looms in Burundi as the country heads to the polls on 20 May amid ongoing repression of the opposition and a surge in clashes between supporters and opponents of the ruling party. -

The Political Ideology and Philosophy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in the Context of Founding a Nation

World Bulletin of Social Sciences (WBSS) Available Online at: https://www.scholarexpress.net Vol. 2 August-September 2021 ISSN: 2749-361X THE POLITICAL IDEOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY OF BANGABANDHU SHEIKH MUJIBUR RAHMAN IN THE CONTEXT OF FOUNDING A NATION Shah Mohammad Omer Faruqe Jubaer 1 Muhammed Nyeem Hassan 2 Article history: Abstract: Received: June 11th 2021 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is regarded as a "liberation emblem." He Accepted: July 26th 2021 was a one-of-a-kind nationalist leader who freed the people of East Pakistan Published: August 20th 2021 (now Bangladesh) from West Pakistan's oppression. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman has played a pivotal role in the Bangladeshi independence movement. He has been dubbed "Father of the Nation" due to his dominating role and presence. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the most towering figure in Bangladeshi politics has been explained, claimed, and counterclaimed by political parties and intellectuals as a secular, a Bengali, and a socialist or a mix of all. As a leader, there is no end to his merits and there is no end to writing about him. There is very little scholastic research on the ideology and political philosophy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, so the Primary object of this Research Paper is to identify and clarify the concept regarding the philosophy and ideology of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman which reflects the guiding principles of The Constitution of the People ’s Republic of Bangladesh. Keywords: Political Ideology, Political Philosophy, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Political Ideology of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Political Philosophy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. INTRODUCTION: People were mesmerized by his magnetism. -

Who' Who Page 2017

Published in the United Kingdom by BBWW Limited Unit 2, 60 Hanbury Street London E1 5JL Tel: 020 7377 8966 Email: [email protected] www.bbwhoswho.co.uk FIRST PRINT NOVEMBER 2017 EDITOR IN CHIEF MOHAMMED ABDUL KARIM EDITOR SHAHADOTH KARIM BARRISTER AT LAW DESIGN AND PRODUCTION IMPRESS MEDIA UK CONTRIBUTORS ANAWAR BABUL MIAH, BARRISTER AT LAW SHEIKH TAUHID KOYES UDDIN MOHAMMED ALI SABIA KHATUN AHAD AHMED SUHANA AHMED FARUK MIAH MBE SAJIA AFRIN CHOWDHURY © BBWW Limited 2017/18 British Bangladeshi Who’s Who 2017 1 2 British Bangladeshi Who’s Who 2017 | Celebrating 10th Anniversary Celebrating 10th Anniversary | British Bangladeshi Who’s Who 2017 3 4 British Bangladeshi Who’s Who 2017 | Celebrating 10th Anniversary Foreword from the Editor in Chief Tis year we celebrate the 10th anniversary of this important publication. Te publication has really gone from strength to strength. When we started we could have only dreamt of this publication continuing and growing at the rate it has. It amazes me that ten years on we continue to unearth some real talent in our community. Of course all of this is possible because of the foundations laid down by the first generation to whom we are indebted. I hope you enjoy this year’s publication and appreciate the success of our award winner and I hope you will continue to support us for many years to come. Mohammed Abdul Karim (Goni) 8th October 2017 Celebrating 10th Anniversary | British Bangladeshi Who’s Who 2017 5 Foreword from the Editor We have reached our first milestone as we celebrate the 10th anniversary of this publication and launch gala dinner. -

List of School

List of School Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Thana AMTALI Sl Eiin Name Village/Road Mobile 1 100003 DAKSHIN KATHALIA TAZEM ALI SECONDARY SCHOOL KATHALIA 01720343613 2 100009 LOCHA JUUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL LOCHA 01553487462 3 100011 AMTALI A.K. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL 437, A K SCHOOL ROAD, 01716296310 AMTALI 4 100012 CHOTONILGONG HIGH SCHOOL CHOTONILGONG 01718925197 5 100014 SHAKHRIA HIGH SCHOOL SHAKHARIA 01712040882 6 100015 GULSHA KHALIISHAQUE HIGH SCHOOL GULISHAKHALI 01716080742 7 100016 CHARAKGACHIA SECONDARY SCHOOL CHARAKGACHIA 01734083480 8 100017 EAST CHILA RAHMANIA HIGH SCHOOL PURBA CHILA 01716203073,0119027693 5 9 100018 TARIKATA SECONDARY SCHOOL TARIKATA 01714588243 10 100019 CHILA HASHEM BISWAS HIGH SCHOOL CHILA 01715952046 11 100020 CHALAVANGA HIGH SCHOOL PRO CHALAVANGA 01726175459 12 100021 CHUNAKHALI HIGH SCHOOL CHUNAKHALI 01716030833 13 100022 MAFIZ UDDIN GIRLS PILOT HIGH SCHOOL UPZILA ROAD 01718101316 14 100023 GOZ-KHALI(MLT) HIGH SCHOOL GOZKHALI 01720485877 15 100024 KAUNIA IBRAHIM ACADEMY KAUNIA 01721810903 16 100026 ARPAN GASHIA HIGH SCHOOL ARPAN GASHIA 01724183205 17 100028 SHAHEED SOHRAWARDI SECONDARY SCHOOL KUKUA 01719765468 18 100029 KALIBARI JR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KALIBARI 0172784950 19 100030 HALDIA GRUDAL BANGO BANDU HIGH SCHOOL HALDIA 01715886917 20 100031 KUKUA ADARSHA HIGH SCHOOL KUKUA 01713647486 21 100032 GAZIPUR BANDAIR HIGH SCHOOL GAZIPUR BANDAIR 01712659808 22 100033 SOUTH RAOGHA NUR AL AMIN Secondary SCHOOL SOUTH RAOGHA 01719938577 23 100034 KHEKUANI HIGH SCHOOL KHEKUANI 01737227025 24 100035 KEWABUNIA SECONDARY -

The Darkest Night and Its Aftermath

International Affairs Sub Committee Bangladesh Awami League THE DARKEST NIGHT AND ITS AFTERMATH International Affairs Sub Committee Bangladesh Awami League Prelude 04 Darkest Night 06 Indemnity for Killers 08 Rehabilitation of Killers 10 First Attempt at Accountability 12 Justice Finally 14 Aftermath of Tragedy 19 Victims of 15 August 1975 20 15 August 1975 stands as the darkest night in the history of independent Bangladesh when the Father of the Nation and First President of Bangladesh Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated along with almost his entire family by a group of wayward army officers as part of a larger national and international political conspiracy. This booklet gives a summary of the tragic events of that fateful night along with the prelude and aftermath of one of the most brutal acts of political violence in history. Prelude civil administration, established United Nations in September 1974. On rehabilitation centers for women 25th September, 1974 Bangabandhu victims of the war, established a trust for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman became the the welfare of the freedom fighters, first Bengali leader to address the undertook several measures to ensure United Nations General Assembly in food security and agricultural revolution Bangla. such as waiving tax upto certain Following a bloody war of liberation, by national and international quarters measures of land, supply of seeds and It was also a time of the cold war involving the genocide of three million counting on Sheikh Mujib’s project to fertilizers among the farmers for free between the two global superpowers, Bengali lives and the sufferings of build a ‘Sonar Bangla’ (a prosperous etc. -

Criminal Appeal Nos. 55 - 59 of 2007 With

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH APPELLATE DIVISION PRESENT: Mr. Justice Md. Tafazzul Islam Mr. Justice Md. Abdul Aziz Mr. Justice B. K. Das Mr. Justice Md. Muzammel Hossain Mr. Justice S. K. Sinha CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS. 55 - 59 OF 2007 WITH JAIL APPEAL No. 02 of 2007 WITH CRIMINAL MISCELLANEOUS PETITION NO.08 OF 2001 WITH CRIMINAL REVIEW PETITION No. 03 of 2000. Major Md. Bazlul Huda (Artillery) ... Appellant (In Crl. Appeal No.55/07, Crl.M.P.08/01 and Crl.R.P. No.03/00). Lieutenant Colonel Syed Faruque Rahman ... Appellant (In Crl. Appeal No.56/07) Lieutenant Colonel Sultan Shahrior Rashid Khan (Retd) .... Appellant (In Crl. Appeal No.57/07) Lieutenant Colonel (Retd). Mohiuddin Ahmed (2nd Artillery) ..... Appellant (In Crl. Appeal No.58/07) Major (Retd). A.K.M. Mohiuddin Ahmed ... Appellant (In Crl. Appeal No.59/07 and Jail Appeal No.02/07) -Versus- The State .... Respondent (In all the cases) For the Appellant : Mr.Abdullah-Al-Mamun, Advocate, (In Crl.A.No.55/07) instructed by Mr. Md. Nurul Islam Bhuiyan, Advocate-on-Record. For the Appellant : Mr.Khan Saifur Rahman, Senior In Crl.A.No.56/07 Advocate, instructed by Mr. Nurul Islam Bhuiyan, Advocate-on-Record. For the Appellant : Mr. Abdur Razzaque Khan, Senior (In Crl.A. No.57/07) Advocate, instructed by Mr. Md. Nawab Ali, Advocate-on-Record. 2 For the Appellant : Mr. Khan Saifur Rahman, Senior Advocate (In Crl. A.No.58/07) instructed by Mr. Md. Nawab Ali, Advocate-on- Record. For the Appellant : Mr. Abdullah-Al-Mamun, Advocate, (In Crl.A. -

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent