1977 Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Disclaimer One Or More of the Following Statements May Affect

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) UCID-30198 COMPUTER DOCUMENTATION REQUIREMENTS FOR MIGRATION OF NSSD CODE SYSTEMS FROM LTSS TO NLTSS UCID--30198 Mike Pratt DE24 009533 February 22, 1984 Ge' I 3n\pt` t an informal report intended primarily for internal or limited external ruli-in. The opinions and conclusions stated are those of the author and r may not be those of the Laboratory. performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by the nce Livermore National Laboratary u.ider Contract W-7405-Eng-48. DISCLAIMER -t was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States :nt. Neither t he United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their , makes any warranty, express or implie.:, or assumes ar.y legal liability or responsi- the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or sclosrl, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owi,cd rights. -

Bibliography

Bibliography App, 2017. (2017). appc: App container specification and tooling. https://github.com/appc/spec. Accetta, M. J., Baron, R. V., Bolosky, W. J., Golub, D. B., Rashid, R. F., Tevanian, A., et al. (1986). Mach: A new kernel foundation for UNIX development. In Proceedings of the USENIX Summer Conference. Ahn, D. H., Garlick, J., Grondona, M., Lipari, D., Springmeyer, B., & Schulz, M. (2014). Flux: A next-generation resource management framework for large HPC centers. In 43rd International Conference on Parallel Processing Workshops (ICCPW), 2014 (pp. 9–17). IEEE. Ajima, Y., Inoue, T., Hiramoto, S., Takagi, Y., & Shimizu, T. (2012). The Tofu interconnect. IEEE Micro, 32(1), 21–31. Akkan, H., Ionkov, L., & Lang, M. (2013). Transparently consistent asynchronous shared mem- ory. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Runtime and Operating Systems for Supercomputers, ROSS ’13. New York, NY, USA: ACM. Alam, S., Barrett, R., Bast, M., Fahey, M. R., Kuehn, J., McCurdy, C., et al. (2008). Early evaluation of IBM BlueGene/P. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing, SC ’08 (pp. 23:1–23:12). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE Press. Ali, N., Carns, P., Iskra, K., Kimpe, D., Lang, S., Latham, R., et al. (2009). Scalable I/O forward- ing framework for high-performance computing systems. In IEEE International Conference on Cluster Computing and Workshops, 2009. CLUSTER ’09 (pp. 1–10). Alverson, B., Froese, E., Kaplan, L., & Roweth, D. (2012). Cray Inc., white paper WP-Aries01- 1112. Technical report, Cray Inc. Alverson, G. A., Kahan, S., Korry, R., McCann, C., & Smith, B. J. -

The Basis System Release 12.1

The Basis System Release 12.1 The Basis Development Team November 13, 2007 Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Email: [email protected] COPYRIGHT NOTICE All files in the Basis system are Copyright 1994-2001, by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. This work was produced at the University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (UC LLNL) under contract no. W-7405-ENG-48 (Contract 48) between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and The Regents of the University of California (University) for the operation of UC LLNL. Copyright is reserved to the University for purposes of controlled dissemination, commercialization through formal licensing, or other disposition under terms of Contract 48; DOE policies, regulations and orders; and U.S. statutes. The rights of the Federal Government are reserved under Contract 48 subject to the restrictions agreed upon by the DOE and University as allowed under DOE Acquisition Letter 88-1. DISCLAIMER This software was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor the University of California nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or the University of California. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or the University of California, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. -

History of Operating Systems

System Architecture History of Operating Systems Some slides from A. D. Joseph, University of Berkeley See also: www.osdata.com/kind/history.htm www.armory.com/~spectre/tech.html courses.cs.vt.edu/~cs1104/VirtualMachines/OS.1.html en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_operating_systems © 2008 Universität Karlsruhe (TH), System Architecture Group 1 Moore’s Law Drives OS Change 1981 2006 Factor CPU MHz, 10 3200x4 1,280 Cycles/inst 3—10 0.25—0.5 6—40 DRAM capacity 128KB 4GB 32,768 Disk capacity 10MB 1TB 100, 000 Net bandwidth 9600 b/s 1 Gb/s 110,000 # addr bits 16 32 2 #users/machine 10 1 0.1 Price $25,000 $4,000 0.2 Typical academic computer 1981 vs 2006 © 2008 Universität Karlsruhe (TH), System Architecture Group 2 Moore’s Law Effects Nothing like this in any other area of business Transportation in over 200 years: Only 2 orders of magnitude from horseback @10mph to Concorde @1000mph Computers do this every decade What does this mean for us? Techniques have to vary over time to adapt to changing tradeoffs Let’s place a lot more emphasis on principles The key concepts underlying computer systems Less emphasis on facts that are likely to change over the next few years… Let’s examine the way changes in $/MIP has radically changed how OS’s work © 2008 Universität Karlsruhe (TH), System Architecture Group 3 Dawn of Time ENIAC: (1945-55) “The machine designed by Eckert and Mauchly was a monstrosity. When it was finished, the ENIAC filled an entire room, weighed 30 tons, and consumed 200 kilowatts of power.” http://ei.cs.vt.edu/~history/ENIAC.Richey.HTML © 2008 Universität Karlsruhe (TH), System Architecture Group 4 History Phase 1: 19481948--7070 Expensive Hardware Cheap Humans © 2008 Universität Karlsruhe (TH), System Architecture Group 5 History of Systems History OS: Evolution Step 0 APP OS Hardware Simple OS: One program, one user, one machine: examples: early computers, early PCs, embedded controllers such as Nintendo, cars, elevators OS just a library of standard services, e.g. -

The. Nor01al College New" S

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU EMU Student Newspaper: The orN mal News & University Archives The Eastern Echo 1917 The orN mal College News, February 2, 1917 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/student_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "The orN mal College News, February 2, 1917" (1917). EMU Student Newspaper: The Normal News & The Eastern Echo. 443. https://commons.emich.edu/student_news/443 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in EMU Student Newspaper: The orN mal News & The Eastern Echo by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The . Nor01al College NeW"s VOL. 14 YPSILANTI, MICHIGAN. FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 2, J 917 �o. 1a Normal Meets Old Platform F�e Tonight! GREEN AND WHITE COURT STARS * THIRD ANNUAL NORMAL-FERRIS :. :A�END:R ,, F�R �T:E W;E : : WIN ANOTHER DOUBLE VICTORY * INSTITUTE ENCOUNTER TONIGHT 'l'ODA0Y, 1•1RJ�AY, �EB. 2 : 8. ��::� Beat M. A. C. Fresh 28-20; Olivet 37-14 0 :� ��;o�7 DdiatP, ea:s� : To be Held in Pease Au ditorium at Iight * �� an a a n Thoe M. A. C. Fresh and Olivet quin- The nu l Norm SAT----, U ftVAY, FhlBtHU.AJH,Y ;J l Ferrisn I stitttte tettes a re the latest twoa foes to be PROF. WEBSTER H. PEARCE DR. C. 0. HOYT TO li : 4-5 Baslcetball. Preliminary ADDRESS dual debate takes place to ight, Bur WILL SPEAK TO Y. -

1993 Cern School of Computing

CERN 94-06 14 October 1994 ORGANISATION EUROPÉENNE POUR LA RECHERCHE NUCLÉAIRE CERN EUROPEAN ORGANIZATION FOR NUCLEAR RESEARCH 1993 CERN SCHOOL OF COMPUTING Scuola Superiore G. Reiss Romoli, L'Aquila, Italy 12-25 September 1993 PROCEEDINGS Eds. C.E. Vandoni, C. Verkerk GENEVA 1994 opyright eneve, 1 Propriété littéraire et scientifique réservée Literary and scientific copyrights reserved in pour tous les pays du monde. Ce document ne all countries of the world. This report, or peut être reproduit ou traduit en tout ou en any part of it, may not be reprinted or trans partie sans l'autorisation écrite du Directeur lated without written permission of the copy général du CERN, titulaire du droit d'auteur. right holder, the Director-General of CERN. Dans les cas appropriés, et s'il s'agit d'utiliser However, permission will be freely granted for le document à des fins non commerciales, cette appropriate non-commercial use. autorisation sera volontiers accordée. If any patentable invention or registrable Le CERN ne revendique pas la propriété des design is described in the report, CERN makes inventions brevetables et dessins ou modèles no claim to property rights in it but offers it susceptibles de dépôt qui pourraient être for the free use of research institutions, man décrits dans le présent document; ceux-ci peu ufacturers and others. CERN, however, may vent être librement utilisés par les instituts de oppose any attempt by a user to claim any recherche, les industriels et autres intéressés. proprietary or patent rights in such inventions Cependant, le CERN se réserve le droit de or designs as may be described in the present s'opposer à toute revendication qu'un usager document. -

IN. J. Tactics in Colonia Stir Fight Going to See Wortf Series?

IN. J. Tactics THE WEATHER OVER Zone Case In Colonia THE WEEK-END In Sewaren WDODHRIIX'iE. N ,1.. THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 1047 i By wire from l;. S. Wttthcr VOL. XXXIX- No. 34 PRICK FIVr. CKNTS Bureau, Washington) Mnl^r^rt HH Kfroml Olnun Matter Stir Fight Tluir*.ln> Is Settled at the Post Office, Wooiihrlilffo, N. .7, <Mi SIffcI. Wii lilK', N J Todir ,,, , Cloudy and cool this afttr- IrespaKH (Jiarge is; noon with utront noHh to north - Board OKs Compromise wind*. Hlgheit Conference In the low «0'i. Clearing and But Minftrily Group I P Putting Their Sunday School Lessons into Practice cooler tonight with lowwt near 1 Promised Monday «0 dMtrrm. Mav Put Up Battle Tomorrow i riii iirivupup* f | coi.ONIA Wilh resentment : running hliih over the manner In F»lr with eonitderablr nun- ! WOODBRIDOE—After weeka of lor I riiscuMion. pro and con, the Board A huh thr Blntr HiRhway Depart- . Hiii.Jnl, nklrh Rhlnr and rather cool with high- j nf Adjustment la.it night voted incut is allegedly appropriating , est temnrrttur* near (I. ', unanimously to recommend to the liuul (tii its new parkway regard- Saturday and Sunday 'Township Committee that the less of ownership. The INDEPEN- I,,,n 11 <> w urc you try- Outlook IK for partly cloudy Royal Petroleum Corporation, Be- OFNT-I.KADER today was insured weather becoming warmer on i 11,( Inch rnst of livinn? warcn. DP permitted to erect four llur, ;i i nnffiTiire will br hold In Sunday. Chance of frost In thr additional tank.1* and the Town- riminii Monday umonK tup Irvcl Vjnlerior of New .renwy Saturday ship acrrpt H riocrl which would ,-. -

Proceedings Fall 1984 Proceedings

PROCEEDINGS FALL 1984 PROCEEDINGS FOURTEENTH SEMI-ANNUAL CRAY USER GROUP MEETING October 1-4, 1984 Hyatt Regency Hotel San Francisco, California Host: Technology Development of California Ron Deiss, Local Arrangements Karen Friedman, Proceedings Editor Prepared for publication and printed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado (NCAR).*,t Cover photograph courtesy of Karen Friedman. Thanks go to Kathy Lucero of NCAR for her assistance in typing various contri butions to these Proceedings. --·--The National Center for Atmospheric Research is operated by the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research and is sponsored by the National Science Foundation. t Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. ii CONTENTS PRELIMINARY INFORMATION CRAY Users Group Board of Directors, 1984-1985. v Members of the Program Committee for Fall 1984, San Francisco • • • • • • • • vi Program, CRAY Users Group, Fall 1984, San Francisco vii PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS Keynote Address: A Large-Scale Computer Facility for Computational Aerodynamics, F.R. Bailey. 3 Cray Research Corporate Report, Don Whiting •• 4 CRAY Software Status, Margaret A. Loftus •••• 6 LINCS, John G. Fletcher. • • • • • • • • • • 7 Continuous Protocol for Long Distance Communication - Links, J. Hughes •••••••• 10 CRI View of Networking, Don M. Mason. • • • • • • • 20 Fortran in the 90's, Jeanne Martin ••••••••• 22 Digital Scene Simulation(s) on CRAY Supercomputers, Larry S. Yaeger • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 25 WORKSHOP REPORTS IIO Workshop, Mostyn Lewis •••••• 33 Languages Workshop, Mary E. Zosel • 34 Front Ends Workshop, Dean W. Smith •• 36 Libraries Workshop, Margaret L. Simmons • 39 Operations Workshop, Gary Jensen •••• 41 Performance Evaluation and Optimization Workshop, J. -

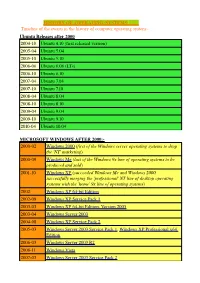

HISTORY of OPERATING SYSTEMS Timeline of The

HISTORY OF OPERATING SYSTEMS Timeline of the events in the history of computer operating system:- Ubuntu Releases after 2000 2004-10 Ubuntu 4.10 (first released version) 2005-04 Ubuntu 5.04 2005-10 Ubuntu 5.10 2006-06 Ubuntu 6.06 (LTs) 2006-10 Ubuntu 6.10 2007-04 Ubuntu 7.04 2007-10 Ubuntu 7.10 2008-04 Ubuntu 8.04 2008-10 Ubuntu 8.10 2009-04 Ubuntu 9.04 2009-10 Ubuntu 9.10 2010-04 Ubuntu 10.04 MICROSOFT WINDOWS AFTER 2000:- 2000-02 Windows 2000 (first of the Windows server operating systems to drop the ©NT© marketing) 2000-09 Windows Me (last of the Windows 9x line of operating systems to be produced and sold) 2001-10 Windows XP (succeeded Windows Me and Windows 2000, successfully merging the ©professional© NT line of desktop operating systems with the ©home© 9x line of operating systems) 2002 Windows XP 64-bit Edition 2002-09 Windows XP Service Pack 1 2003-03 Windows XP 64-bit Edition, Version 2003 2003-04 Windows Server 2003 2004-08 Windows XP Service Pack 2 2005-03 Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 1, Windows XP Professional x64 Edition 2006-03 Windows Server 2003 R2 2006-11 Windows Vista 2007-03 Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 2 2007-11 Windows Home Server 2008-02 Windows Vista Service Pack 1, Windows Server 2008 2008-04 Windows XP Service Pack 3 2009-05 Windows Vista Service Pack 2 2009-10 Windows 7(22 occtober 2009), Windows Server 2008 R2 EVENT IN HISTORY OF OS SINCE 1954:- 1950s 1954 MIT©s operating system made for UNIVAC 1103 1955 General Motors Operating System made for IBM 701 1956 GM-NAA I/O for IBM 704, based on General Motors -

Lllbltilpllilsfelisl"! Iâuuldlnhu

,lrV/| ' w ¦'.¦¦'¦'-• L - ímiM Fundado em IWI^ii^Aai" 9 F \Z AGENCIA NO BIO Numero do tlia, 100 réisala'-'«^=55*^ tmÊ*\mm\\^sm Bua da Alfândega, 86 atrasado, 200. réis ÜLISTANO i» (SOBRADO) CORRFIOPPE UMA«A -SOCIEDADESC ANONYMA PROPRIEDADE AaaUnttturaa Urasll-Anaú . , J5$(XK) | Exterior-Anno , 40$0C0 Ki*daccão c sidmlnlslrucuo S. Paulo - Sexta-feira, ffi de Outubro de 1912 • licmoitre, líi$0001 • «eiiioitre 25JD00 Dr. Antônio Prado (Palacole Ilrlocola) meaA Onlxa — U «Jo Correio ^^^m^^g^^t^^^^mmmggl^Ut\mWt\mtmWÊtmm.mmmmm^^^^^^^^^^^Z^ —==— tacto oom a raia p«r|iiguoza, — medoia- MA1R0C03 rani apenas as horaa «ruo vao, desdo cer.» OSFRANCEZES EM ca da moia noito dg&;4 para 5, ató as 2 da tardo de 0, quer^dizor umas 38 ho- ras, durante aa qua«Me executaram con* secntivamonte; sei*ç«||»canço, todos o» trabalhos int*rmetHá||ifc ,— desembar» qtio, onrrogamontiS^^^wtomovois, trajtv «¦»"²""- aos ho- oto destes,'descarga^ ^distribuição j mens, o 30 kilométtóK",do marciia destos.» uA força cffoetiM^a columna iior oc» casião da entrada «fSjjSiciitava-se l>or »C0 espingardas o 2'pçiOTrae montanha, a 100 "liCV-^iÈinlamciito tiros estno. a aquellas. Ií, demais, tun rudjytvtar arremedo do serviços sanitário'..«administrativo. exercito invasor, «Pouco docerto, fj^.a'l*>'íhvia, «íião se tratava, do invasão, i nem muito menos r^vòwiquwtn, — mas iDopin KTM.ÍI" "dfttí««»lta a uma Ban» liltlulU pAili aponas de sorvir lllBlTIlPllilSFEliSl"! iâUulDlnHU-. deira, armada, seguroidizem, pela gran- do maioria do Paizí^Esoolta da llaiidoi- da Azul o Branca, ni-fla -

Timeline of Operating Systems - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Timeline of operating systems - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_operating_systems Timeline of operating systems From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article presents a timeline of events in the history of computer operating systems from 1951 to 2009. For a narrative explaining the overall developments, see the History of operating systems. Contents 1 1950s 2 1960s 3 1970s 4 1980s 5 1990s 6 2000s 7 See also 7.1 Category links 8 References 9 External links 1950s 1951 LEO I 'Lyons Electronic Office'[1] was the commercial development of EDSAC computing platform, supported by British firm J. Lyons and Co. 1954 MIT's operating system made for UNIVAC 1103[2] 1955 General Motors Operating System made for IBM 701[3] 1956 GM-NAA I/O for IBM 704, based on General Motors Operating System 1957 Atlas Supervisor (Manchester University) (Atlas computer project start) BESYS (Bell Labs), for IBM 7090 and IBM 7094 1958 University of Michigan Executive System (UMES), for IBM 704, 709, and 7090 1959 SHARE Operating System (SOS), based on GM-NAA I/O 1 of 16 2/24/11 9:28 PM Timeline of operating systems - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_operating_systems 1960s 1960 IBSYS (IBM for its 7090 and 7094) 1961 CTSS (MIT's Compatible Time-Sharing System for the IBM 7094) MCP (Burroughs Master Control Program) 1962 Atlas Supervisor (Manchester University) (Atlas computer commissioned) GCOS (GE's General Comprehensive Operating System, originally GECOS, General Electric Comprehensive -

Navigating the Attack Surface

Verify what? Navigating the Attack Surface Mark S. Miller, Google Formal Methods meets JavaScript Imperial College, March 2018 Risk as Attack Surface a Expected Risk: ∫likelihood * damage Potential damage Likelihood of exploitable vulnerability a Expected Risk: ∫likelihood * damage Resources to damage Fallible agents a Access Matrix Permission or Authority? Resources to damage Fallible agents a Hollow Out the Attack Surface! /etc/passwd Alan’s stuff Barb’s stuff Doug’s stuff Kernel + root OS’s TCB ~alan ~barb ~doug a Decouple accounts /etc/passwd Alan’s stuff Barb’s stuff Doug’s stuff Kernel + root OS’s TCB ~alan ~barb ~doug a a Decouple applications contact info pgp keyring calc.xls Net access Shell, Desktop Browser Spreadsheet Email client a Decouple apps contact info pgp keyring calc.xls Net access MobileOS Doug’s TCB Browser app Spreadsheet doc Mail a app Decouple apps contact info pgp keyring calc.xls Net access MobileOS Doug’s TCB Browser app Spreadsheet doc Mail a app Substrate Historical System System CMNM, Plessey 250, C.mmp, CM*, Crash-SAFE, CHERI, Risc-V Hardware CAP, Flex, IBM System/38, Intel 432 DVH, Hydra, StarOS, RATS, Capsicum, CloudABI, Genode, OS Cal-TSS, PSOS, NLTSS, Spring Barrelfish, Fuchsia Gnosis, KeyKOS, GuardOS, seL4 KeyKOS family OS EROS, CapROS, Coyotos Distributed OS Ameoba, Mach, Midori Gedanken, W7, J-Kernel, Joe-E, Emily, Monte, Frozen Realms, Language CaPerl, Caja, Tamed Pict, Plash shill, Wyvern, wasm-gc Act-1, Eden, Emerald, Pony, Kappa, Dr.SES Distributed Language Vulcan, Joule, E, Oz-E, M# Distributed Storage