Signature Redacted for Privacy. Abstract Approved: Arol Sisson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yes, No, Maybe Chart Instructions

Yes, No, Maybe Chart Instructions Instructions If Using With A Partner or Partners: 1. Print It: Print out one chart for each person who will be participating, plus one extra as a master list. (Feel free to add any sex acts I missed, or take out sex acts that don’t apply to your body.) 2. Fill It Out: Have each person fill out the chart (preferably alone) based upon their personal preferences. Check “Yes” if you would do this activity. Check “No” if you would not engage in the activity. Check “Maybe” if you would consider doing the activity, need more information about the activity, or are not completely opposed to the activity. BE HONEST. The whole point of this is to help express desires, and if you’re not honest, this exercise won’t be completely effective. 3. Make A Master List: Once forms are filled out, use the extra chart you printed out to compile a master list. Compare your charts and when your yes columns match up, put a mark in the “YES” column. When your no columns match up, put a mark in the “NO” column. When your maybe columns match up OR when your marks don’t match up, put a mark in pencil in the “MAYBE” column. 4. Negotiate: Discuss the acts in the “MAYBE” column. If you can come to an agreement in either direction, erase your mark in the “MAYBE” column, and place one in either the “YES” or “NO” column based on your decision. If an agreement can’t be reached, or if you’re still unsure, keep the mark in the “MAYBE” column. -

Kink Activity List for Date

Kink Activity List for Date A blank under Experience = Yes No Under Willingness = Yes No Notes 1. This version is intended for Bottoms & Switches with their Bottom hat on 2. ? Don't understand this item. 3. No under Willingness is a hard limit, subject to any notes 4. Flogging is defined as mild to moderate (& occasionally severe) with multi-tailed implements 5. Whipping is defined as severe usually with a single-tail or very wicked implement 6. Novices may change the Experience column heading to: Blank = No 7. For # put a number from 1 (barely tolerate) to 10 (love it!) for how much you like the activity. Experience Willingness # Notes & Nuances Blank = ? Blank = ? Including any medical concerns Anal penetration (properly prepared) - cock Anal penetration - dildo/butt plug/fingers Anal plug (public, under clothes) Animal play (sex with real animals) Arm & leg sleeves (arm/leg binders) Aromas Auctioned for charity Anilingus/rimming (oral/anal play) Beating anywhere on body (soft/moderate) Beating anywhere on body (hard) Blindfolds Being serviced sexually by other subs Being bitten Blood play (rose canes, vampire gloves, etc.) Boot worship/polishing Bondage – usually rope, other types too (light) Bondage (heavy) Bondage (multi-day) Bondage (public, under clothing) Bondage (Intricate Japanese rope) Branding (cell popping method) 1 Kink Activity List for Date A blank under Experience = Yes No Under Willingness = Yes No Experience Willingness # Notes & Nuances Blank = ? Blank = ? Including any medical concerns Branding (violet wand) Branding -

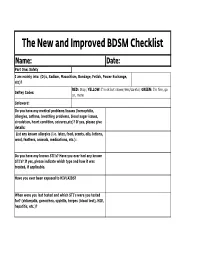

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist Name: Date: Part One: Safety I am mainly into: (D/s, Sadism, Masochism, Bondage, Fetish, Power Exchange, etc)? RED: Stop; YELLOW: I'm ok but slower/less/careful; GREEN: I'm fine, go Saftey Codes: on, more Safeword: Do you have any medical problems/issues (hemophilia, allergies, asthma, breathing problems, blood sugar issues, circulation, heart condition, seizures,etc)? If yes, please give details: List any known allergies (i.e. latex, food, scents, oils, lotions, wool, feathers, animals, medications, etc.): Do you have any known STI's? Have you ever had any known STI's? If yes, please indicate which type and how it was treated, if applicable. Have you ever been exposed to HIV/AIDS? When were you last tested and which STI's were you tested for? (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes (blood test), HIV, hepatitis, etc.)? Have you received any STI vaccinations (i.e. hepatitis A & B or HPV)? How often do you practice safe sex (always, most of the time, some of the time, never)? Please explain reasons for not doing so. Medications: Have you taken any medication, including Asprin within the last 4-6 hours (Asprin changes your blood's clotting time). Please include a list of all prescription and over the counter medications you are currently taking: Visible brusies, cuts, or marks must be avoided (yes or no)? Please list any no hit zones, if any: Do you have any phobias or fears that the Dom/Domme should be aware of (blood, needles, enclosed areas, etc.)? Do you want aftercare (yes, no, only in certain circumstances, unsure, etc.)? Please explain. -

Sugestão De Simbolização Das Práticas BDSM

GasMask™ Sugestão de Simbolização das Práticas BDSM Versão 0.1 © 2009 Copyright. Propriedade de GasMask. Todos os direitos reservados. GasMask™ 1 - Introdução Tendo em vista que no meio BDSM não há uma padronização e um órgão regulador, este trabalho vem por sugerir a simbolização das principais práticas do meio. Este trabalho não tem o intuito de segregar, generalizar ou estereotipar as práticas identificadas, mas sim organizá-las e manter um padrão de visualização a fim de que possam ser identificadas universalmente. Pelo fato de cada praticamente ter uma visão e opinião sobre a classificação de cada prática, é possível que a classificação não esteja de acordo com a visão de cada pessoa, por isto este projeto estará em constante refinamento até chegar a um consenso geral. A principio este projeto irá abordar as práticas de forma genérica. © 2009 Copyright. Propriedade de GasMask. Todos os direitos reservados. GasMask™ 2 – A Padronização A padronização das formas e desenhos foram inspiradas nas placas de aviso padrão NIOSH, OSHA e Hommel. Fig 1: Exemplos de placas de aviso inspiradas. A padronização das práticas BDSM darão-se pela classificação de três macro-grupos: Práticas Classificadas como Regular Play Práticas Classificadas como Role Play Práticas Classificadas como Edge Play Sendo cada um destes grupos simbolizado por uma forma geométrica diferente, sendo: Um Quadrado, para Regular Play Um Círculo, para Role Play Um Triângulo, para EdgePlay Fig 2: Formas Representação Macro das práticas. Respectivamente, Role Play, Regular Play e Edge Play. A justificativa das formas utilizadas para simbolizar os macro-grupos se deve à sua representação do grupo: Quadrado (Regular Play): Atividades mais comuns, “quadradas”, que não se encaixam nas outras classificações. -

ROUGHBS BDSM Negotiation Tool

ROUGH BS & Kinky y/n/m BDSM pre-negotiation tools ROUGH BS is a preliminary BDSM pre-negotiation tool used to outline RESTRAINED limits and determine compatibility between potential scene members. This system also helps the Dominant construct a scene geared toward OWNED the submissives needs and desires. USED Go through each category to the left and determine how much you enjoy engaging in that activity as a submissive. Use a 1-10 scale with 1 GIVEN AWAY being the least and 10 the greatest. HUMILIATED To determine specific interests and limits, go through the items below BEATEN responding to each in a Yes/No/Maybe format. Have all parties discuss their responses to each item. Be sure to also take into account any SERVE allergies, medical conditions, triggers or aftercare concerns. Kinky yes/no/maybe list Abduction play Exhibitionism/public play Phone sex Age play Eye contact restrictions Pain (mild to severe) Anal sex Face Sitting Piercing Anal rimming Face slapping Pet Play Anal plugs Feeding Pinching Anonymous sex Felatio (Giving/Receiving) Pornography (Watching/making) Balloons Financial Pregnancy Beating (Hands, Implements) Fisting (Anal/Vaginal) Prolapse Being sexually serviced Flogging Punishment Scene Bisexuality Following orders Pussy/cock whipping/spanking Biting Food play/Sploshing Rape play Blindfolds Foot worship Riding crops Blood play Furry fetish Taboo play Bondage, Suspension/Heavy Gags (race/religion/etc.) Bondage, Shibari/decorative Group sex/gang-bang Saline injection Branding Hair pulling Scat Breath Play Hairbrush -

Submissive BDSM Play Partner Check List

Princess Honeybee's BDSM Play Partner Information and Checklist Items for discussion: 1. Consent Do all partners give consent to play? Under what terms? For what length of time? Notes: _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ What are the submissive or bottom's limits? _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ What are the Dominant or top's limits? _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Stopping play and Safewords What will each partner do if a need to pause or stop play arises for any of the following reasons: Physical pain: ____________________________________________________________________ Emotional distress: ________________________________________________________________ Medical need: ____________________________________________________________________ -

Salirophilia and Other Co-Occurring Paraphilias in a Middle-Aged Male: a Case Study

Journal of Concurrent Disorders Vol. 1 No. 2, 2019 Salirophilia and other co-occurring paraphilias in a middle-aged male: A case study MARK D. GRIFFITHS Psychology Department School of Social Sciences Nottingham Trent University Burton Street, Nottingham, NG1 4BU United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Abstract Salirophilia is a paraphilic sexual fetish in which individuals experience sexual arousal from soiling or disheveling the object of their desire. To date, there has been no academic or clinical research into salirophilia, and there are no published peer-reviewed papers – not even a single case study. Therefore, this paper presents the first case study account of a salirophile, a 58-year-old heterosexual male. The areas of interest that were examined included his background relating to childhood experiences of sex, other co- occurring paraphilic interests, and a detailed overview of his engagement in salirophilic acts. It was found that his interest in salirophilic acts dated back to his childhood, and based on the account given, the behavior is most likely explained by classical conditioning. It was also found that there were many other paraphilic behaviors that co-occurred with salirophilia, including sadism, urophilia, coprophilia, and zoophilia. The case study highlights the importance of online methods in the recruitment of individuals and the collection of data with sexually paraphilic behavior for academic study. Keywords: salirophile, case, classical conditioning. Introduction paraphilic disorder, and a paraphilia by itself does According to the latest (fifth) edition of the not necessarily justify or require clinical Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental intervention” (pp. 865-866).