Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

August 25, 2021 the Honorable Merrick Garland Attorney General

MARK BRNOVICH DAVE YOST ARIZONA ATTORNEY GENERAL OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL August 25, 2021 The Honorable Merrick Garland Attorney General 950 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Re: Constitutionality of Illegal Reentry Criminal Statute, 8 U.S.C. § 1326 Dear Attorney General Garland, We, the undersigned attorneys general, write as chief legal officers of our States to inquire about your intent to appeal the decision in United States v. Carrillo-Lopez, No. 3:20-cr- 00026-MMD-WGC, ECF. 60 (D. Nev. Aug. 18, 2021). As you know, in that decision, Chief Judge Du found unconstitutional 8 U.S.C. § 1326, the statute that criminalizes the illegal reentry of previously removed aliens. We appreciate that you recently filed a notice of appeal, preserving your ability to defend the law on appeal. We now urge you to follow through by defending the law before the Ninth Circuit and (if necessary) the Supreme Court. We ask that you confirm expeditiously DOJ’s intent to do so. Alternatively, if you do not intend to seek reversal of that decision and instead decide to cease prosecutions for illegal reentry in some or all of the country, we ask that you let us know, in writing, so that the undersigned can take appropriate action. Section 1326, as part of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, is unremarkable in that it requires all aliens—no matter their race or country of origin—to enter the country lawfully. In finding the law racially discriminatory against “Latinx persons,” Chief Judge Du made some truly astounding claims, especially considering that, under the Immigration and Nationality Act, Mexico has more legal permanent residents in the United States, by far, than any other country.1 Chief Judge Du determined that, because most illegal reentrants at the border are from Mexico, the law has an impermissible “disparate impact” on Mexicans. -

Document Future Danger (Including Past Violence Where the Same Regime Prohibited Their Right to Self-Defense), the Regime Fails Muster Under Any Level of Scrutiny

No. 20-843 In the Supreme Court of the United States NEW YORK STATE RIFLE & PISTOL ASSOCIATION, INC., ET AL., Petitioners, v. KEVIN P. BRUEN, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF NEW YORK STATE POLICE, ET AL., Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit BRIEF OF ARIZONA, MISSOURI, ALABAMA, ALASKA, ARKANSAS, FLORIDA, GEORGIA, IDAHO, INDIANA, KANSAS, KENTUCKY, LOUISIANA, MISSISSIPPI, MONTANA, NEBRASKA, NEW HAMPSHIRE, NORTH DAKOTA, OHIO, OKLAHOMA, SOUTH CAROLINA, SOUTH DAKOTA, TENNESSEE, TEXAS, UTAH, WEST VIRGINIA, AND WYOMING AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS MARK BRNOVICH ERIC S. SCHMITT Arizona Attorney Missouri Attorney General General JOSEPH A. KANEFIELD D. JOHN SAUER Chief Deputy Solicitor General BRUNN W. ROYSDEN III JEFF JOHNSON Solicitor General Deputy Solicitor General DREW C. ENSIGN Deputy Solicitor General OFFICE OF THE MISSOURI Counsel of Record ATTORNEY GENERAL ANTHONY R. NAPOLITANO Supreme Court Building Assistant Attorney General 207 West High Street OFFICE OF THE ARIZONA P.O. Box 899 ATTORNEY GENERAL Jefferson City, MO 65102 2005 N. Central Ave. (573) 751-3321 Phoenix, AZ 85004 [email protected] (602) 542-5025 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae (Additional Counsel listed on inside cover) Additional Counsel STEVE MARSHALL DANIEL CAMERON Attorney General Attorney General of Alabama of Kentucky TREG TAYLOR JEFF LANDRY Attorney General Attorney General of Alaska of Louisiana LESLIE RUTLEDGE LYNN FITCH Attorney General Attorney General of Arkansas of Mississippi ASHLEY MOODY AUSTIN KNUDSEN Attorney General Attorney General of Florida of Montana CHRISTOPHER M. CARR DOUGLAS J. PETERSON Attorney General Attorney General of Georgia of Nebraska LAWRENCE G. -

Stetson in the News

Stetson In the News Oct. 27-Nov. 2 Top Stories: John Rasp, Ph.D., associate professor of statistics at Stetson University, was quoted in the article, "Cross- Disciplinary Collaboration Encourages Conversations About Teaching," posted by the Chronicle of Higher Education Online Oct. 26. Rasp was also mentioned in the Chronicle of Higher Education Online article, "Talking Teaching With Your Colleagues," posted Oct. 27. K.C. Ma, Ph.D., professor of finance at Stetson University, was quoted in the article, "5 of the Best Stocks to Buy for November." Ma said, "Alibaba's dominance is insulated from international completion through the government, and domestically they are the preferred marketplace for both consumers and merchants," posted by MSN Money US (en) and U.S. News & World Report Nov. 1. Law Professor Charles Rose was quoted by Law 360 regarding the Engle sanctions. He was also quoted in the Oct. 31 Daytona Beach News-Journal article, "Jurors will have to be unanimous for death sentence against Luis Toledo." In partnership with the Florida Humanities Council, Stetson University will be presenting "The Rivers Run To It." The event is part of the Florida Humanities Speaker Series and will feature Jack Davis, Ph.D., posted by Capital Soup Nov. 1. Law Professor Ciara Torres-Spelliscy was quoted in the Nov. 1 The Globe and Mail Online article, "Mueller's Russia investigation extends beyond collusion." Other News: Law Professor Rebecca Morgan wrote the Nov. 1 Elder Law Prof Blog post, "What is the Difference Between Original Medicare and Part C?" Professor Morgan also wrote the Oct. -

January 12, 2021 the Honorable Jeffrey A. Rosen Acting Attorney

January 12, 2021 The Honorable Jeffrey A. Rosen Acting Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, DC 20530 Dear Acting Attorney General Rosen: We, the undersigned state attorneys general, are committed to the protection of public safety, the rule of law, and the U.S. Constitution. We are appalled that on January 6, 2021, rioters invaded the U.S. Capitol, defaced the building, and engaged in a range of criminal conduct—including unlawful entry, theft, destruction of U.S. government property, and assault. Worst of all, the riot resulted in the deaths of individuals, including a U.S. Capitol Police officer, and others were physically injured. Beyond these harms, the rioters’ actions temporarily paused government business of the most sacred sort in our system—certifying the result of a presidential election. We all just witnessed a very dark day in America. The events of January 6 represent a direct, physical challenge to the rule of law and our democratic republic itself. Together, we will continue to do our part to repair the damage done to institutions and build a more perfect union. As Americans, and those charged with enforcing the law, we must come together to condemn lawless violence, making clear that such actions will not be allowed to go unchecked. Thank you for your consideration of and work on this crucial priority. Sincerely Phil Weiser Karl A. Racine Colorado Attorney General District of Columbia Attorney General Lawrence Wasden Douglas Peterson Idaho Attorney General Nebraska Attorney General Steve Marshall Clyde “Ed” Sniffen, Jr. Alabama Attorney General Acting Alaska Attorney General Mark Brnovich Leslie Rutledge Arizona Attorney General Arkansas Attorney General Xavier Becerra William Tong California Attorney General Connecticut Attorney General Kathleen Jennings Ashley Moody Delaware Attorney General Florida Attorney General Christopher M. -

Hawaii Continues Fight to Protect the Affordable Care Act

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR CLARE E. CONNORS ATTORNEY GENERAL For Immediate Release News Release 2019-26 May 23, 2019 Hawaii Continues Fight to Protect the Affordable Care Act Attorney General Joins Coalition of 21 Attorneys General Challenging Plaintiffs’ Lack of Standing in Texas v. US HONOLULU – Attorney General Clare E. Connors, joined a coalition led by Attorney General Becerra of 20 states and the District of Columbia, in filing a response in Texas v. U.S., defending the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the healthcare of tens of millions of Americans. The brief, filed in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on Wednesday, argues that every provision of the ACA remains valid. It further argues that the position taken by the Trump Administration and the Texas-led coalition is legally incorrect and dangerous to our healthcare system. "This is another important step in our ongoing efforts to ensure affordable health care for Hawaii residents and millions of other Americans," Attorney General Connors said. The plaintiffs, two individuals and 18 States led by Texas, filed this lawsuit in February 2018, challenging one provision of the Affordable Care Act—the requirement that individuals maintain health insurance or pay a tax. Texas’ lawsuit came after Congress reduced that tax to zero dollars in December 2017. Opponents of the ACA had attempted and failed to repeal the ACA over 70 times since its instatement. The plaintiffs argued that this reduction in the tax made the minimum coverage provision unconstitutional. They further argued that this provision could not be “severed” from the rest of the ACA, meaning that the entire Act must be struck down. -

July 12, 2021 VIA EMAIL Director, Office of Public Records 107 West

July 12, 2021 VIA EMAIL Director, Office of Public Records 107 West Gaines Street, Suite 228 Tallahassee, FL 32399-1050 [email protected] Re: Public Records Request Dear Public Records Officer: Pursuant to Article I, section 24(a), of the Florida Constitution, and Florida’s public records laws, as codified at Fla. Stat. Chapter 119, American Oversight makes the following request for records. Requested Records American Oversight requests that the Florida Office of the Attorney General promptly produce the following: 1. All email communications (including emails, email attachments, complete email chains, and calendar invitations) between (a) Attorney General Ashley Moody, or anyone communicating on Moody’s behalf, such as a chief of staff, scheduler, or assistant, and (b) the former U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) officials listed below: DOJ Officials a. Deputy Associate Attorney General Brian Pandya b. Deputy Assistant Attorney General Daniel Feith c. Associate Deputy Attorney General Christopher Grieco d. Senior Counselor Brady Toensing e. Senior Counselor Gary Barnett For item 1 of this request, please provide all responsive records from September 20, 2020, through January 20, 2021. 2. All email communications (including emails, email attachments, complete email chains, calendar invitations, and calendar invitation attachments) between (a) Attorney General Ashley Moody, or anyone communicating on Moody’s behalf, such as a chief of staff, scheduler, or assistant, and (b) the external individuals listed below that (c) contain the key terms specified below. 1030 15th Street NW, Suite B255, Washington, DC 20005 | AmericanOversight.org External Individuals a. Elizabeth Murrill, Louisiana Solicitor General b. Benjamin Flowers, Ohio Solicitor General c. -

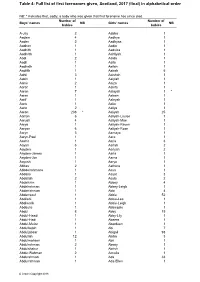

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) In

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2017 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A-Jay 2 Aabha 1 Aadam 4 Aadhya 1 Aaden 2 Aadhyaa 1 Aadhan 1 Aadia 1 Aadhith 1 Aadvika 1 Aadhrith 1 Aahliyah 1 Aadi 2 Aaida 1 Aadil 1 Aaila 1 Aadirath 1 Aailah 1 Aadrith 1 Aairah 5 Aahil 3 Aaishah 1 Aakin 1 Aaiylah 1 Aamir 2 Aaiza 1 Aaraf 1 Aakifa 1 Aaran 7 Aalayah 1 * Aarav 1 Aaleen 1 Aarif 1 Aaleyah 1 Aariv 1 Aalia 1 Aariz 2 Aaliya 1 Aaron 236 * Aaliyah 25 Aarron 6 Aaliyah-Louise 1 Aarush 4 Aaliyah-Mae 1 Aarya 1 Aaliyah-Raven 1 Aaryan 6 Aaliyah-Rose 1 Aaryn 3 Aamaya 1 Aaryn-Paul 1 Aara 1 Aashir 1 Aaria 3 Aayan 6 Aariah 2 Aayden 1 Aariyah 2 Aayden-James 1 Aarla 1 Aayden-Jon 1 Aarna 1 Aayush 1 Aarya 1 Abbas 2 Aathera 1 Abbdelrahmane 1 Aava 1 Abdalla 1 Aayat 3 Abdallah 2 Aayla 2 Abdelkrim 1 Abbey 4 Abdelrahman 1 Abbey-Leigh 1 Abderrahman 1 Abbi 4 Abderraouf 1 Abbie 52 Abdilahi 1 Abbie-Lee 1 Abdimalik 1 Abbie-Leigh 1 Abdoulie 1 Abbiegale 1 Abdul 8 Abby 19 Abdul-Haadi 1 Abby-Lily 1 Abdul-Hadi 1 Abeera 1 Abdul-Muizz 1 Aberdeen 1 Abdulfattah 1 Abi 7 Abduljabaar 1 Abigail 93 Abdullah 12 Abiha 3 Abdulmohsen 1 Abii 1 Abdulrahman 2 Abony 1 Abdulshakur 1 Abrish 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Accalia 1 Abdurahman 1 Ada 33 Abdurrahman 1 Ada-Ellen 1 © Crown Copyright 2018 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB -

Charles G. Gross

Charles G. Gross BORN: New York City February 29, 1936 EDUCATION: Harvard College, A.B. (Biology, 1957) University of Cambridge, Ph.D. (Psychology, 1961) APPOINTMENTS: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1961) Harvard University (1965) Princeton University (1970) VISITING APPOINTMENTS: Harvard University (1963) University of California, Berkeley (1970) Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1975) University of Rio de Janeiro (1981, 1986) Peking University (1986) Shanghai Institute of Physiology (1987) Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Neuroscience (1988) University of Oxford (1990, 1995) HONORS AND AWARDS (SELECTED): Eagle Scout (1950) Finalist, Westinghouse Science Talent Search (1953) Phi Beta Kappa (1957) International Neuropsychology Symposium (1975) Society of Experimental Psychologists (1994) Brazilian Academy of Science (1996) American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1998) National Academy of Sciences (1999) Distinguished Scientifi c Contribution Award, American Psychological Association (2004) Charlie Gross and his colleagues described the properties of single neurons in inferior temporal cortex of the macaque and their likely role in object and face recognition. They also pioneered in the study of other extra-striate cortical visual areas. Many of his students went on to make distinguished contributions of their own. Charles G. Gross was born on February 29 in 1936. My parents, apparently anxious of my feeling deprived of an annual birthday, celebrated my birthday for 2 or I3 days in the off years and even more in the leap years. I was technically a “red diaper baby.” My parents were active Commu- nist Party members. In fact, however, I never heard the term red diaper baby or knew of my parents’ longstanding party membership until I was in grad- uate school, years after my father had lost his job because of his politics. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 20-1029 In the Supreme Court of the United States ____________________ CITY OF AUSTIN, TEXAS, Petitioner, v. REAGAN NATIONAL ADVERTISING OF AUSTIN, INC., ET AL. Respondents. ____________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE U.S. COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT _______________________________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE FLORIDA, ARKANSAS, CALIFORNIA, CONNECTICUT, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, ILLINOIS, IOWA, MAINE, MARYLAND, MASSACHUSETTS, MICHIGAN, MINNESOTA, MISSISSIPPI, NEVADA, NEW JERSEY, NEW YORK, OHIO, OREGON, PENNSYLVANIA, SOUTH DAKOTA, VERMONT, AND WASHINGTON IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER _______________________________________________________________________________ ASHLEY MOODY DAVID M. COSTELLO Attorney General Assistant Solicitor General HENRY C. WHITAKER Office of the Florida Solicitor General Attorney General Counsel of Record PL-01, The Capitol DANIEL W. BELL Tallahassee, Florida 32399 Chief Deputy (850) 414-3300 Solicitor General henry.whitaker@ KEVIN A. GOLEMBIEWSKI myfloridalegal.com Deputy Solicitor General Counsel for Amicus Curiae the State of Florida (Additional counsel with signature block) i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 1 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 3 I. THE FIFTH CIRCUIT ERRED BY CONCLUDING THAT PETITIONER’S ORDINANCE IS CONTENT-BASED UNDER REED. .................................................... -

Distributor Settlement Agreement

DISTRIBUTOR SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT Table of Contents Page I. Definitions............................................................................................................................1 II. Participation by States and Condition to Preliminary Agreement .....................................13 III. Injunctive Relief .................................................................................................................13 IV. Settlement Payments ..........................................................................................................13 V. Allocation and Use of Settlement Payments ......................................................................28 VI. Enforcement .......................................................................................................................34 VII. Participation by Subdivisions ............................................................................................40 VIII. Condition to Effectiveness of Agreement and Filing of Consent Judgment .....................42 IX. Additional Restitution ........................................................................................................44 X. Plaintiffs’ Attorneys’ Fees and Costs ................................................................................44 XI. Release ...............................................................................................................................44 XII. Later Litigating Subdivisions .............................................................................................49 -

Letters to the U.S. House and U.S. Senate

April 29, 2021 Senator Patrick Leahy Senator Richard Shelby Chair Ranking Member U.S. Senate Committee U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations on Appropriations 437 Russell Building 304 Russell Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Jeanne Shaheen Senator Jerry Moran Chair Ranking Member U.S. Senate Committee on U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations Appropriations Subcommittee on Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, Commerce, Justice, Science, & Related Agencies & Related Agencies 506 Hart Building 521 Dirksen Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Re: State Attorneys General Support the Legal Services Corporation Dear Chair DeLauro, Ranking Member Granger, Chair Cartwright, and Ranking Member Aderholt, As state attorneys general, we respectfully request that you consider robust funding for the Legal Services Corporation (LSC) in the Fiscal Year 2022 Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations bill. Since 1974, LSC funding has provided vital and diverse legal assistance to low-income Americans including victims of natural disasters, survivors of domestic violence, families facing foreclosure, and veterans accessing earned benefits. Today, LSC also provides essential support for struggling families affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As the single largest funder of civil legal aid in the United States, LSC-funded programs touch every corner of our country with more than 800 offices and a presence in every congressional district. LSC funding has also fostered public-private partnerships between legal aid organizations and private firms and attorneys across the country which donate their time and skills to assist residents in need. Nationwide, 132 independent nonprofit legal aid programs rely on this federal funding to provide services to nearly two million of our constituents on an annual basis.