Abraham, Hagar and Ishmael at Mecca a Contribution to the Problem of Dating Muslim Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUCCOT Insightsrabbi Yaakov Asher Sinclair

SPECIAL SUCCOT EDITION 5760 PARSHIOT VZOT HABERACHA BEREISHET NOACH VOL. 7 NO. 1 OO H R NN E T THE OHR SOMAYACH TORAH MAGAZINE ON THE INTERNET SUCCOT INSIGHTSRabbi Yaakov Asher Sinclair DRY LIPS IN PRAYER remembered. Why is the arava, him, so too G-d loves the least of us which represents the least of the and takes pleasure from our Jewish People, celebrated above all attempts to please Him, however he four species, the etrog, the other species? dry and limited our attempts may lulav, hadas and arava corre- T The message of the arava is that be. spond to parts of the human body. The lulav is the spine; the G-d loves our prayers. The lips of a ANY OLD RUBBISH? Jew are his most precious posses- etrog the heart; the hadas the eyes f you think about it, a succah is a and the arava the lips. sion. And even when our prayers seem dry and empty like the arava, peculiar thing. We take great The four species also correspond I when they come from a humble pains to deck it out so that it to four kinds of Jew: The etrog has heart, G-d loves them, listens to becomes our home away from both smell and taste. It represents them and accepts them. home. We take in our finest table- the Jew who has both Torah and ware and furnishings. We bedeck it good deeds. The lulav, the palm, like a princess with all manner of has taste but no smell. It repre- jewelry and decoration. -

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title the Jews used in their Hebrew Old Testament for this book comes from the fifth word in the book in the Hebrew text, bemidbar: "in the wilderness." This is, of course, appropriate since the Israelites spent most of the time covered in the narrative of Numbers in the wilderness. The English title "Numbers" is a translation of the Greek title Arithmoi. The Septuagint translators chose this title because of the two censuses of the Israelites that Moses recorded at the beginning (chs. 1—4) and toward the end (ch. 26) of the book. These "numberings" of the people took place at the beginning and end of the wilderness wanderings and frame the contents of Numbers. DATE AND WRITER Moses wrote Numbers (cf. Num. 1:1; 33:2; Matt. 8:4; 19:7; Luke 24:44; John 1:45; et al.). He apparently wrote it late in his life, across the Jordan from the Promised Land, on the Plains of Moab.1 Moses evidently died close to 1406 B.C., since the Exodus happened about 1446 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1), the Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years (Num. 32:13), and he died shortly before they entered the Promised Land (Deut. 34:5). There are also a few passages that appear to have been added after Moses' time: 12:3; 21:14-15; and 32:34-42. However, it is impossible to say how much later. 1See the commentaries for fuller discussions of these subjects, e.g., Gordon J. -

And This Is the Blessing)

V'Zot HaBerachah (and this is the blessing) Moses views the Promised Land before he dies את־ And this is the blessing, in which blessed Moses, the man of Elohim ְ ו ז ֹאת Deuteronomy 33:1 Children of Israel before his death. C-MATS Question: What were the final words of Moses? These final words of Moses are a combination of blessing and prophecy, in which he blesses each tribe according to its national responsibilities and individual greatness. Moses' blessings were a continuation of Jacob's, as if to say that the tribes were blessed at the beginning of their national existence and again as they were about to begin life in Israel. Moses directed his blessings to each of the tribes individually, since the welfare of each tribe depended upon that of the others, and the collective welfare of the nation depended upon the success of them all (Pesikta). came from Sinai and from Seir He dawned on them; He shined forth from יהוה ,And he (Moses) said 2 Mount Paran and He came with ten thousands of holy ones: from His right hand went a fiery commandment for them. came to Israel from Seir and יהוה ?present the Torah to the Israelites יהוה Question: How did had offered the Torah to the descendants of יהוה Paran, which, as the Midrash records, recalls that Esau, who dwelled in Seir, and to the Ishmaelites, who dwelled in Paran, both of whom refused to accept the Torah because it prohibited their predilections to kill and steal. Then, accompanied by came and offered His fiery Torah to the Israelites, who יהוה ,some of His myriads of holy angels submitted themselves to His sovereignty and accepted His Torah without question or qualification. -

Chronology of Wilderness Wanderings

mark h lane www.biblenumbersforlife.com CHRONOLOGY OF WILDERNESS WANDERINGS INTRODUCTION It matters where things happened in the Bible. It matters when things happened in the Bible. The Bible tells us only a few dates. Only a handful of locations are undisputed. One thing we know for absolute sure is Mt. Sinai is in Arabia (Gal. 1:17 4:25). The traditional location of Mt. Sinai is wrong. In the time of Paul Arabia did not extend past the Gulf of Aqaba. Believe the Bible, it is the word of God. SUMMARY We subscribe to the conclusions of Bible.ca who propose the following map of the wilderness journey: There are three wilderness journeys: the first [Red Arrows] is from Goshen in Egypt to Mount Sinai (first white spot); the second [Blue Arrows] is from Mount Sinai to Kadesh Barnea (second white spot); the third [Yellow arrows] is from Kadesh Barnea to Jericho (third spot). Bible.ca provides more detailed maps. However, we like this high level view because the precise location of Mt. Sinai and Kadesh Barnea cannot be proven. The main point for the Bible student to realise is all of what is called the Sinai Peninsula today was part of Egypt until 106 AD when the Romans annexed it. The whole purpose of the Exodus was to draw God’s people out of Egypt. If Mt. Sinai was in Egypt the whole mission would have Bible.ca provides solid arguments why the traditional Red Sea routes been a failure. cannot fit the Biblical account. The route they propose fits Paul tells us Mt. -

The PDF File

THE LOCATION OF MT SINAI: A RESPONSE TO DR MICHAEL HEISER • Dr. Heiser on his Naked Bible Podcast program 260 repeatedly stated that Jebel al Lawz cannot be the real Mount Sinai and should be abandoned as a candidate. • In doing so, he made several significant errors. • I e-mailed him to discuss these errors, but he was not receptive. • I then invited him to have a public discussion on his own podcast or my program, but he was not willing to do so. • I then invited him to a public debate, but he was dismissive. The following is a review of Heiser’s primary errors: 1 • First, Heiser misinterprets a series of texts (Deut 33; Judges 5; Habakkuk 3) to be part of a “Yahweh from the South” tradition. • This view essentially interprets these texts as referring to Yahweh’s southern origin. • As we will see, these are not “Yahweh from the South” texts that talk about “Yahweh’s origin.” • Instead, they are part of a larger tradition that uses Exodus language while ultimately pointing to the Second Exodus. • Jesus and the New Testament writers interpret these traditions as pointing to Jesus’ Second Coming. • Heiser argues that because these texts use parallelisms, Sinai, Seir, Edom, Paran, Teman all of these places are either the same, or located within the same narrow region. • Jebel al-Lawz he argues, is simply too far south to be included among these other mountains and locations. “Not only do you have Sinai linked to Seir, which is this Edomite region south of Canaan, but we have Mount Paran as the place that Yahweh came forth from. -

Abraham’S Life and Times

Abraham’s Life and Times Shem, and Abraham lives over-lap Because of laziness, boredom, we skip “the begets” Noah was 600 years old when the flood came and he lived 950 years From the birth of Arphaxad, two years after the flood, until the birth of Abram it was only 292 years Noah lived 350 years after the flood and Shem 500 years . Noah was Abraham’s great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great- grandfather! Abraham’s Life and Times Shem, he begot Arphaxad, Shem lived five hundred years, and begot sons and daughters. Arphaxad lived thirty-five years, and begot Salah. Salah lived thirty years great, , and begot Eber. Eber lived thirty-four years, and begot Peleg. Peleg lived thirty years, and begot Reu. Reu lived thirty-two years, and begot Serug. Serug lived thirty years, and begot Nahor. Nahor lived twenty-nine years, and begot Terah. Now Terah lived seventy years, and begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran. (Gen 11:10-26) Abraham’s Life and Times Abraham was a semi‐nomadic shepherd to whom God revealed himself, made promises, and entered into covenant concerning Abraham’s offspring and the land that they would inherit in the future Abraham’s belief in these promises was counted by God as righteousness and his faith shaped his life. Ultimately these promises find their fulfillment in Jesus the Messiah and all those who trust in Yahweh, the true God, Abraham’s spiritual children Abraham’s Life and Times Abraham was called both a Hebrew (14:13) and an Aramean (Deuteronomy 26:5; cf. -

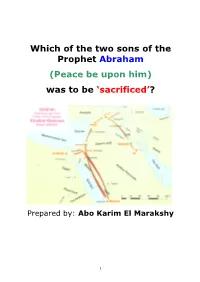

Which of the Two Sons of Prophet Abraham PBUH Was to Be Sacrificed?

Which of the two sons of the Prophet Abraham (Peace be upon him) was to be ‘sacrificed’? Prepared by: Abo Karim El Marakshy 1 The aim of this article is to answer the following misconceptions. 1-Which of the two sons of Prophet Abraham PBUH was to be sacrificed? 2-Hagar’s marriage to Abraham. 3-Ishmael’s relationship with Abraham peace be upon them. 4-The building of the Ka’abah. 5-Prophecies from the Bible about the prophet Muhammad (may Peace and Blessings be upon him). 6-The well of Zamzam. 7-Muslims pilgrimage. 8-Muslims’ claim of being affiliated to Prophet Abraham and various other Islamic articles of faith. PBUH: Peace be upon him 2 The following map shows the journeys of Prophet Abraham (Ibrahim) Peace be upon him Round 1800 B.C. Historical background Allah, the Exalted, inspired Abraham (Ibrahim) to take his wife Hagar (Hajar in Arabic) and his son Ishmael ( Isma'il in Arabic ,Yishma'el ( ) in Hebrew meaning "God hears") peace be upon them to Makkah (Bakkah , Baca) in the Arabian Peninsula. Amazingly enough, this word Baca was mentioned by the prophet David (PBUH) in the Bible: "Who passing through the valley of Baca make it a well, the rain also filleth the pools." (Psalm 84:6) Also the word Baca was mentioned in the Noble Qur'an "Verily, the first house (of worship) appointed for mankind was that in Baka (Mecca), full of blessing, 3 and guidance for all people." 3:96 of the Noble Qur'an. Abraham (Ibrahim) made a new settlement in Makkah, called Mountains of Paran (Pharan) in the Bible (Genesis 21:21), because of a divine instruction that was given to him as a part of Allah's plan. -

Abraham's Three Visitors 18

Es – Abraham’s Three Visitors 18: 1-8 | 1 Abraham’s Three Visitors 18: 1-8 Abraham’s three visitors DIG: Who were the three visitors? How do we know? How can angels appear as men? Even with hospitality of strangers being mandatory in the Near East, how does Abraham go the extra mile for his three visitors? Why is he in such a hurry? REFLECT: Whom can you serve in the name of Messiah this week? Do you have a sense of urgency about your ministry? What evidence is there of it? How eager are you to hear what the Lord has to say to you? Are you standing close enough to ADONAI that you can hear His gentle whisper (First Kings 19:12)? Parashah 4: vaYera (He appeared) 18:1-22:24 (see my commentary on Deuteronomy, to see link click Af – Parashah) The Key People include three angels, Abraham, Sarah, Lot, Abimelech, Isaac, Hagar, Ishmael, and the descendants of Nahor. The Scenes include the trees of Mamre in Hebron, Sodom and Gomorrah, Zoar, the Negev, Gerar, Beersheba, the desert of Paran, and Moriah. The Main Events include the angels’ visit, the promise of a son, Sarah’s laugh, Sodom destroyed, the sister deception part two, Isaac born, Hagar and Ishmael cast out, treaty, the binding of Isaac, and God’s provision of a ram. ADONAI appeared to Avraham. The rabbis teach that God came to visit him as he was recovering from circumcision (17:9-14). The place was near the great trees of Mamre while he was sitting, apparently praying and meditating, at the entrance to his tent in the heat of the day, or early in the afternoon (18:1). -

What Every Christian High School Student Should Know About Islam - an Introduction to Islamic History and Theology

WHAT EVERY CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT SHOULD KNOW ABOUT ISLAM - AN INTRODUCTION TO ISLAMIC HISTORY AND THEOLOGY __________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Theology Liberty University __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry __________________ by Bruce K. Forrest May 2010 Copyright © 2010 Bruce K. Forrest All rights reserved. Liberty University has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. APPROVAL SHEET WHAT EVERY CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT SHOULD KNOW ABOUT ISLAM - AN INTRODUCTION TO ISLAMIC HISTORY AND THEOLOGY Bruce K. Forrest ______________________________________________________ "[Click and enter committee chairman name, 'Supervisor', official title]" ______________________________________________________ "[Click here and type committee member name, official title]" ______________________________________________________ "[Click here and type committee member name, official title]" ______________________________________________________ "[Click here and type committee member name, official title]" Date ______________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge all my courageous brothers and sisters in Christ who have come out of the Islamic faith and have shared their knowledge and experiences of Islam with us. The body of Christ is stronger and healthier today because of them. I would like to acknowledge my debt to Ergun Mehmet Caner, Ph.D. who has been an inspiration and an encouragement for this task, without holding him responsible for any of the shortcomings of this effort. I would also like to thank my wife for all she has done to make this task possible. Most of all, I would like to thank the Lord for putting this desire in my heart and then, in His timing, allowing me the opportunity to fulfill it. -

The Twelve Spies Caleb

THE DOWNRIVER DISCIPLES PROJECT explores THE TWELVE SPIES CALEB The journey of the Twelve Spies can be found in the Old So, following the directions given by Moses, off the Testament (1) book of Numbers (2), the 4th book of the Twelve went into Canaan, During their travels, they cut Holy Bible (3). The narrative in Numbers 13:1-33 dis- a branch containing a cluster of grapes to bring back closes the account of a group of Israelite leaders who from their journey. After 40 (13) days, the Twelve ended were hand selected by Moses (4) to scout Canaan, the their exploration and returned to their people. Upon land set aside by God (5) Himself as the future home for arrival back in the Desert of Paran, the Twelve Spies the Twelve Tribes of Israel (6) after their Exodus from gave a report to Moses, Aaron (14) and the entire com- Egypt (7) (explore Exodus 12:31-42). munity. They showed everyone the branch of grapes they brought back and shared that the land did, indeed, (NOTE: The region of Canaan is also known as the flow with milk and honey. But there were naysayers "Promised Land" (8) as it was previously promised by within the Twelve, who disclosed they saw powerful the LORD to Abraham (9) (Genesis 12:1-7, Genesis 15:1- people and large, fortified cities in Canaan. This 20) and his descendants. This sworn oath was subse- brought in a fear over the Israelites. quently reaffirmed by the LORD with Abraham's son, Isaac (10) (Genesis 26:1-6), and again with Abraham's Caleb, one of the Twelve and an obedient (15) servant of grandson, Jacob (11) (Genesis 28:10-15). -

Women of the Bible: the Story of Hagar

Bible Study Wednesday May 4, 2016 Women of the Bible: The Story of Hagar Part 1: Scripture Verse: Genesis 16, 21:8-21; Galatians 4:22-31 Now Sarai, Abram’s wife, bore him no children. She had an Egyptian slave-girl whose name was Hagar, and Sarai said to Abram, “You see that the Lord has prevented me from bearing children; go in to my slave-girl; it may be that I shall obtain children by her.” And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai. So, after Abram had lived ten years in the land of Canaan, Sarai, Abram’s wife, took Hagar the Egyptian, her slave-girl, and gave her to her husband Abram as a wife. He went in to Hagar, and she conceived; and when she saw that she had conceived, she looked with contempt on her mistress. Then Sarai said to Abram, “May the wrong done to me be on you! I gave my slave-girl to your embrace, and when she saw that she had conceived, she looked on me with contempt. May the Lord judge between you and me!” But Abram said to Sarai, “Your slave-girl is in your power; do to her as you please.” Then Sarai dealt harshly with her, and she ran away from her. The angel of the Lord found her by a spring of water in the wilderness, the spring on the way to Shur. And he said, “Hagar, slave-girl of Sarai, where have you come from and where are you going?” She said, “I am running away from my mistress Sarai.” The angel of the Lord said to her, “Return to your mistress, and submit to her.” The angel of the Lord also said to her, “I will so greatly multiply your offspring that they cannot be counted for multitude.” And the angel of the Lord said to her, “Now you have conceived and shall bear a son; you shall call him Ishmael, for the Lord has given heed to your affliction. -

8 Uplifting Lessons from the Life of Ishmael Pamela Palmer | Author 2021 20 May

8 Uplifting Lessons from the Life of Ishmael Pamela Palmer | Author 2021 20 May Photo credit: Unsplash Abraham is one of the most important figures in the Old Testament. He had a profound faith and a vibrant relationship with God. Though not perfect, Abraham had a heart for God that can be seen in how he interacted with God and trusted that God would fulfill mighty promises in his life. God’s promise to Abraham that he would have descendants was a radical promise made to Abraham and his wife, who were old in age. Despite that, Abraham went on to have two sons: Ishmael, whom he had with Hagar, and Isaac, whom he had with Sarah. Due to escalating tension between Sarah and Hagar, Abraham sent Ishmael and his mother away. God, however, had not forgotten about Ishmael and Hagar. He assured Abraham that though his son Ishmael would be sent away, He would also build a nation through Ishmael to fulfill His promise (see Genesis 21:12-13). Ishmael’s story is one of sorrow and pain, yet when we consider the life of Ishmael, there is much we as believers can learn. Here are eight lessons we can learn from the life of Ishmael. Who Was Ishmael? “So, Hagar bore Abram a son, and Abram gave the name Ishmael to the son she had borne. Abram was eighty-six years old when Hagar bore him Ishmael” (Genesis 15:16). Ishmael was the firstborn son of Abraham. He was born to Abraham by his slave, Hagar. Sarah, Abraham’s wife, believed that since she was old and barren, God’s promise of children to Abraham could only be fulfilled through Hagar.