Foreign Language Trademarks in Japan: the Linguistic Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPERT DETERMINATION LEGAL RIGHTS OBJECTION Merck & Co

ARBITRATION AND MEDIATION CENTER EXPERT DETERMINATION LEGAL RIGHTS OBJECTION Merck & Co, Inc. v. Merck KGaA Case No. LRO2013-0068 1. The Parties Objector/Complainant is Merck & Co, Inc., United States of America, represented by Reed Smith LLP, United States of America. Applicant/Respondent is Merck KGaA, Germany, represented by Bettinger Schneider Schramm, Germany. 2. The applied-for gTLD string The applied-for gTLD string is <.emerck> (the “Disputed gTLD String”). 3. Procedural History The Legal Rights Objection (“LRO”) was filed with the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (the “WIPO Center”) on March 13, 2013 pursuant to the New gTLD Dispute Resolution Procedure (the “Procedure”). An amended Objection was filed with the WIPO Center on March 27, 2013. In accordance with Article 9 of the Procedure, the WIPO Center has completed the review of the Objection on March 28, 2013 and has determined that the Objection complies with the requirements of the Procedure and the World Intellectual Property Organization Rules for New gTLD Dispute Resolution for Existing Legal Rights Objections (the “WIPO Rules for New gTLD Dispute Resolution”). In accordance with Article 11(a) of the Procedure, the WIPO Center formally notified Applicant of the Objection, and the proceedings commenced on April 16, 2013. In accordance with Article 11(b) and relevant communication provisions of the Procedure, the Response was timely filed with the WIPO Center on May 15, 2013. The WIPO Center appointed Willem J.H. Leppink as the Panel in this matter on June 14, 2013. The Panel finds that it was properly constituted. The Panel has submitted the Statement of Acceptance and Declaration of Impartiality and Independence, as required by the WIPO Center to ensure compliance with Article 13(c) of the Procedure and Paragraph 9 of WIPO Rules for New gTLD Dispute Resolution. -

“Dead Copies” Under the Japanese Unfair Competition Prevention Act: the New Moral Right

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 51 Number 1 Fall 2006 Article 5 2006 “Dead Copies” Under the Japanese Unfair Competition Prevention Act: The New Moral Right Kenneth L. Port William Mitchell College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth L. Port, “Dead Copies” Under the Japanese Unfair Competition Prevention Act: The New Moral Right, 51 St. Louis U. L.J. (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol51/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW “DEAD COPIES” UNDER THE JAPANESE UNFAIR COMPETITION PREVENTION ACT: THE NEW MORAL RIGHT KENNETH L. PORT* INTRODUCTION In 1993, the Japanese legislature, or Diet, amended the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) to prevent the slavish copying (moho) of another’s product configuration (shohinno keitai) regardless of registration, regardless of notice of any kind, regardless of whether the configuration was distinctive in 1 any way, and regardless of whether any consumer was confused or deceived. * Professor of Law and Director of Intellectual Property Studies, William Mitchell College of Law. J.D., University of Wisconsin. I am deeply indebted to Laurie Sheen (WMCL ‘07) and Toshiya Kaneko (University of Tokyo) for their assistance with this article. This article was researched while I was a Foreign Research Fellow at the Tokyo University Business Law Center under the gracious auspices of Professor Nobuhiro Nakayama. -

Trademark Public Search in India Faqs – Part 2

Trademark public search in India FAQs – Part 2 Continuing with our article on FAQs on trademark public search in India, we present you second part on FAQs related to trademark search in India. Q – Why trademark public search is important? A – Trademark search is one of the most important steps in trademark registration. A through trademark search can prevent your brand name being infringed and reduces risk of loosing a brand name due to a inadequate trademark search. Q – Can you do trademark search on your own? A – Yes, you can perform trademark public search on your own. You can check our guide on step by stepIPIndia trademark search. Though, it is always advised to take help of external professional service providers for trademark public search as it tend to be more professional and less time consuming. Q – When should you do a TM Search? A – Ideally, trademark public search should be done before filing a application for a trademark registration. You don’t want your application to be rejected by examiner due to lack of or incomplete trademark search. Moreover, search should also be conducted post registration of trademark also. As this step would make sure that your registered trademark is not being used by someone else. Q – How to do trademark search? A – Trademark search can be performed with help of different databases such as IPIndia trademark portal, Ministry of corporate affairs, common law database and Madrid system. You should collect information related to each keyword and formulate a decision matrix to outline chances of your selected trademark getting through examination. -

Overview of Japanese Trademark Law

Overview of Japanese Trademark Law 2nd Edition Shoen Ono 注: これは、日本語で書かれた『商標法概説[第2版]』(有斐閣、1999)の英訳です。 原著者に翻訳及び公開の許可をいただき公開しております。翻訳については財団法人 知的財産研究所(現在、一般財団法人知的財産研究教育財団 知的財産研究所)が翻訳 事業者に依頼して作成した英訳であり、原著者及び弊所は日本語版と英語版の間に生じ 得る差異について責任を負いません。テキストに対する公式な言及、またその引用を行 う場合には、オリジナルの日本語版に当たり確認してください。 Note: This is the English translation from “Overview of Japanese Trademark Law [2nd ed.]” (Yuhikaku, 1999), written in Japanese. The original author has given permission for translation and publication. The translation was created by a translation company at the request of Institute of Intellectual Property (Currently: Foundation for Intellectual Property, Institute of Intellectual Property). The original author or Foundation for Intellectual Property, Institute of Intellectual Property is not responsible for any discrepancies that may exist between the Japanese and English versions. Readers are recommended to confirm the original Japanese version when formally referencing or citing the text. PART 1. INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTORY STATEMENTS CHAPTER 2: THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF TRADEMARK LAW CHAPTER 3: THE CONCEPT OF THE TRADEMARK LAW CHAPTER 4: SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE TRADEMARK LAW PART 1. INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTORY STATEMENTS Significance of Trademark Protection Trademarks play a vital role in day to day choices made by the consuming public. Consider the effect of trademarks on those who purchase goods and receive services, consumers. Consumers rely on trademarks, for example, to more easily facilitate repeat purchases of goods or services based on a previous pleasurable experience or a manufacturer’s reputation for quality. Trademarks enable consumers to make repeated purchases without extensive research. A critical trait of a strong mark is that it uniquely serves to identify source. Marks that are similar not only inadequately designate true origin, but can actually suggest the wrong origin, encouraging confusion and misleading consumers. -

Mere Allegations of Bad Faith Insufficient Under UDRP, Even in Obvious Cybersquatting Cybersquatting Cases International - Hogan Lovells LLP

Mere allegations of bad faith insufficient under UDRP, even in obvious Cybersquatting cybersquatting cases International - Hogan Lovells LLP June 10 2013 In a recent decision under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), the panel has held that the mere registration of domain names consisting of obvious misspellings of a trademark, without supporting evidence of bad-faith registration and use, is insufficient to obtain the transfer of the domain names. The complainant, Ticket Software LLC (Connecticut, United States), owned the US trademark TICKETNETWORK (Registration No 2,956,502), registered on May 31 2005 and used in connection with computer software for the purchase and sale of entertainment tickets. The complainant operates a website at ‘www.ticketnetwork.com’, where it has created an online marketplace for sale of entertainment tickets. The respondent was Stephen Troy, a private individual from Florida, United States, who had registered the domain names ‘ricketnetwork.com’, ‘ticketneteork.com’, ‘ticketnetwirk.com’, ‘ticketnetworj.com’ and ‘tivketnetwork.com’ using a proxy service provided by the domain name registrar. The domain names were registered on January 13 2011 and did not point to an active website. The complainant contended that the respondent had engaged in typosquatting, given that the domain names consisted of common typographical errors made by internet users when attempting to reach the complainant's official website, and thus filed a complaint under the UDRP to recover the domain names. To be successful in a complaint under the UDRP, a complainant must satisfy all of the following three requirements: l The domain name is identical, or confusingly similar, to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant has rights; l The respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name; and l The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith. -

Well-Known Trademark Protection

WIPO SIX MONTH STUDY - CUM - RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP Well -Known Trademark Protection Reference to the Japanese experience Final Report In Fulfillment of the Long Term Fellowship Sponsored By: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in Collaboration with the Japan Patent Office April 2 - Septembe r 30, 2010 Submitted By: Hà Th Nguy t Thu National Office of Intellectual Property of Vietnam (NOIP) 384 -386 Nguyen Trai, Thanh Xuan, Ha Noi, Vietnam Supervised By: Prof. Kenichi MOROOKA National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) 7-22 -1 Roppongi, Minato -ku, Tokyo 1 06 -8677, JAPAN This report is a mandatory requirement of this fellowship; views and findings are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policy considerations of his organization or sponsor of this study. 1 WIPO SIX MONTH STUDY - CUM - RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP Page INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION 1 1. Overview of research theme 1 2. Some misunderstanding definitions: famous 2 trademark, well -known trademark, widely - known trademark, trademark with high reputation 3. The function of trademarks and protection 6 trademark CHAPTER 1 INTERNATIONAL FRAMWORK OF 10 WELL -KNOWN TRADEMARKS PROTECTION 1.1 . Paris Convention 10 1.2 . TRIPs Agreement 12 1.3 . WIPO Joint Recommendations concerning 14 provisions on Protection of Well -known Marks CHAPTER 2 WELL -KNOWN TRADEMARKS 15 PROTECTION UNDER JAPANESE LAW 2.1. Protection o f well -known trademark under the 15 Trademark Law (JTL) 2.1.1. Prohibition of Registration of a mark identical or 15 similar to well -known/famous trademark of others 2.1.2. Expansion of Protection of well -known 30 trademarks 2.2. -

Myanmar Study on Cooperation for the Establishing of Intellectual Property Office

Myanmar Ministry of Science and Technology Myanmar Study on Cooperation for the Establishing of Intellectual Property Office Final Report March 2014 Japan International Cooperation Agency Kyoto Comparative Law Center Oh-Ebashi LPC & Partners IL JR 14-039 Contents Map of Myanmar Abstract Chapter I: Introduction 1.1 Background ···················································································· 1 1.2 Framework of the Survey ·································································· 1 1.3 Survey Target ·················································································· 4 1.4 Activities and Schedule ······································································ 4 1.5 Survey Method ·············································································· 5 1.6 Survey Itinerary ············································································· 7 Chapter II: Current Status of Intellectual Property Law System 2.1 Current Status of Intellectual Property Law System ····································· 11 2.1.1 Overview of Intellectual Property Law System ····································· 11 2.1.2 Trademark Law ·········································································· 11 2.1.3 Patent Law ················································································ 16 2.1.4 Industrial Design Law ·································································· 17 2.1.5 Copyright Law ··········································································· 18 -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

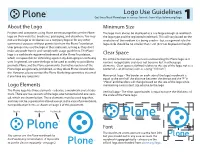

Logo Use Guidelines

Logo Use Guidelines Get the ocial Plone logo in various formats from http://plone.org/logo 1 About the Logo Minimum Size Projects and companies using Plone are encouraged to use the Plone The logo must always be displayed at a size large enough to read both logo on their websites, brochures, packaging, and elsewhere. You may the logo type and the registered trademark. This will vary based on the not use the logo or its likeness as a company logo or for any other resolution of the medium it is being used in - but as a general rule the commercial purpose without permission from the Plone Foundation. logo circle should be no smaller than 1 cm (3/8”) or 36 pixels in height. User groups may use the logo in their materials, as long as they don't make any prot from it and comply with usage guidelines. The Plone logo is a worldwide registered trademark of the Plone Foundation, Clear Space which is responsible for defending against any damaging or confusing It is critical to maintain an open area surrounding the Plone logo so it uses. In general, we want the logo to be used as widely as possible to remains recognizable and does not become lost in other page promote Plone and the Plone community. Derivative versions of the elements. Clear space is dened relative to the size of the logo, not as a Plone logo are generally prohibited, as they dilute Plone's brand iden- border of a set distance (such as saying “1/4 inch”.) tity. -

Introduction to Trademark Law and Practice

WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION INTRODUCTION TO TRADEMARK LAW & PRACTICE THE BASIC CONCEPTS A WIPO TRAINING MANUAL GENEVA 1993 (Second Edition) ( ( WIPO PUBLICATION No 653 (El ISBN 92-805-0167-4 WIPO 1993 PREFACE The present publication is the second edition of a volume of the same title that was published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 1987 and reprinted in 1990. The first edition was written by Mr. Douglas Myall, former Assistant Registrar of Trade Marks, United Kingdom. The present revised edition of the publication has been prepared by Mr. Gerd Kunze, Vevey, Switzerland, and reflects his extensive expertise and experience in the administration of the trademark operations of a large international corporation, Nestle S. A., as well as his intensive involvement, as a leading representative of several international non-governmental organizations, in international meetings convened by WIPO. This publication is intended to provide a practical introduction to trademark administration for those with little or no experience of the subject but who may have to deal with it in an official or business capacity. Throughout the text, the reader is invited to answer questions relating to the text. Those questions are numbered to correspond to the answers that are given, with a short commentary, in Appendix I. Arpad Bogsch Director General World Intellectual Property Organization February 1993 ( ( LIST OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. TRADEMARKS AND OTHER SIGNS: A GENERAL SURVEY 7 1.1 Use of trademarks in commerce . 9 1.2 What is a trademark?. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 1.3 Need for legal protection .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 1.4 How can a trademark be protected? . -

I Trademark Classification

APPENDIX I I Trademark Classification • Goods o Class 1 Chemicals used in industry, science and photography, as well as in agriculture, horticulture and forestry; unprocessed artificial resins, unprocessed plastics; manures; fire extinguishing compositions; tempering and soldering prepara tions; chemical substances for preserving foodstuffs; tanning substances; adhesives used in industry. o Class 2 Paints, varnishes, lacquers; preservatives against rust and against deterioration of wood; colorants; mordants; raw natural resins; metals in foil and powder form for painters, decorators, printers and arts. o Class 3 Bleaching preparations and other substances for laundry use; cleaning, polishing, scouring and abrasive preparations; soaps; perfumery, essential oils, cosmetics, hair lotions; dentifrices. o Class 4 Industrial oils and greases; lubricants; dust absorbing, wetting and binding compositions; fuels (including motor spirit) and illuminates; candles, wicks. o Class 5 Pharmaceutical, veterinary and sanitary preparations; dietetic substances adapted for medical use, food for babies; plasters, materials for dressings; material for stopping teeth, dental wax; disinfectants; preparations for destroying vermin; fungicides, herbicides. 112 Trademark Classification 113 o Class 6 Common metals and their alloys; metal building materials; transportable buildings of metal; materials of metal for railway tracks; non-electric cables and wires of common metal; ironmongery, small items of metal hardware; pipes and tubes of metal; safes; goods of -

MAKING a MARK an Introduction to Trademarks for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

Intellectual Property for Business Series Number: 1 MAKING A MARK An Introduction to Trademarks for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION Publications in the “Intellectual Property for Business” series: 1. Making a Mark: An Introduction to Trademarks for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. WIPO publication No. 900. 2. Looking Good: An introduction to Industrial Designs for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. WIPO publication No. 498. 3. Inventing the Future: An introduction to Patents for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. WIPO publication No. 917. 4. Creative Expression: An introduction to Copyright for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. WIPO publication No. 918 (forthcoming). All publications available from the WIPO e-bookshop at: www.wipo.int/ebookshop Disclaimer: The information contained in this guide is not meant as a substitute for professional legal advice. Its purpose is to provide basic information on the subject matter. www.wipo.int/sme/ WIPO Copyright (2006) No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, except as permitted by law, without written permission from the owner of the copyright. Preface This guide is the first in a series of guides on “Intellectual Property for Business.” It is devoted to trademarks, a central element in the marketing and branding strategy of any company. This guide seeks to explain trademarks from a business perspective. Its approach is practical and explanations are illustrated with examples and pictures to enhance the reader’s understanding. Small and Medium-sized Entreprises (SMEs) are encouraged to use the guide with a view to integrating their trademark strategy into their overall business strategy.