Serial Verbs in Waanyi and Its Neighbours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Linguistic Research Findings to Useful Products for Australian Aboriginal Communities

etropic 12.1 (2013): TransOceanik Special Edition | 73 From Linguistic Research Findings to Useful Products for Australian Aboriginal Communities Mary Laughren School of Languages and Comparative Cultural Studies The University of Queensland Abstract As a linguist investigating the Warlpiri language of central Australia since 1975 and the Waanyi language of the Gulf of Carpentaria region since 2000, my research has always had dual goals. One is to gain a better understanding of the nature of human language generally through detailed documentation and deep analysis of particular human languages, such as Warlpiri and Waanyi, and comparison with other languages; the other goal has been to produce materials of direct relevance and utility to the communities of these language speakers. This paper addresses the second goal. Firstly I briefly describe ways in which linguistic research findings have been 'converted' into pedagogic materials to support the bilingual education programs in the Warlpiri community schools (Lajamanu, Nyirrpi, Willowra and Yuendumu) from the mid 1970s to the present, a period which has seen dramatic technical innovations that we have been able to exploit to create a wide range of products accessible to the public which have their genesis in serious linguistic research. Secondly I discuss some aspects of the interdisciplinary (linguistics and anthropology) “Warlpiri Songlines” project (2005-9) for which over 100 hours of traditional Warlpiri songs were recorded and documented; older analogue recordings were digitised and ceremonial performances were video recorded. Thirdly, I touch upon the ongoing development of a Waanyi dictionary and language learning materials in collaboration with Waanyi people living at Doomadgee in north west Queensland who want to extend knowledge of their ancestral language within their community, since this language is no longer used as a primary language of communication. -

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic Studies of the Cranial Shape The

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic studies of the cranial shape The measurement of the human head of both the living and dead has long been a matter of interest to a variety of professions from artists to physicians and latterly to anthropologists (for a review see Spencer 1997c). The shape of the cranium, in particular, became an important factor in schemes of racial typology from the late 18th Century (Blumenbach 1795; Deniker 1898; Dixon 1923; Haddon 1925; Huxley 1870). Following the formulation of the cranial index by Retzius in 1843 (see also Sjovold 1997), the classification of humans by skull shape became a positive fashion. Of course such classifications were predicated on the assumption that cranial shape was an immutable racial trait. However, it had long been known that cranial shape could be altered quite substantially during growth, whether due to congenital defect or morbidity or through cultural practices such as cradling and artificial cranial deformation (for reviews see (Dingwall 1931; Lindsell 1995). Thus the use of cranial index of racial identity was suspect. Another nail in the coffin of the Cranial Index's use as a classificatory trait was presented in Coon (1955), where he suggested that head form was subject to long term climatic selection. In particular he thought that rounder, or more brachycephalic, heads were an adaptation to cold. Although it was plausible that the head, being a major source of heat loss in humans (Porter 1993), could be subject to climatic selection, the situation became somewhat clouded when Beilicki and Welon demonstrated in 1964 that the trend towards brachycepahlisation was continuous between the 12th and 20th centuries in East- Central Europe and thus could not have been due to climatic selection (Bielicki & Welon 1964). -

Managing Indigenous Pastoral Lands

module three land information MANAGING INDIGENOUS PASTORAL LANDS Pub no. 14/019 McClelland Rural Services Pty Ltd MODULE 3 land information Contents Introduction 3 List of Tables Indigenous Land Rights and Pastoral Figure 3.1 Map of Northern Territory Land Holdings 5 Aboriginal Land 7 Land Rights 5 Figure 3.2 Map of Queensland Indigenous Pastoral Land Holdings 5 Aboriginal Land 8 Land Tenure 10 Figure 3.3 Map of Western Australian Indigenous Lands - Aboriginal Land (Kimberley & Pilbara) 9 Definitions and Complexities 10 Indigenous Land Holding Arrangements List of Photos in the Northern Territory 11 Cover Photo – Ghost gums Legal Framework 11 Permitted Land Uses 11 Indigenous Land Holding Arrangements in Queensland 12 Legal Framework 12 Forms of Land Acquisition 12 Renewals of Pastoral Leases 13 Indigenous Land Holding Arrangements in Western Australia 14 Legal Framework 14 Forms of Land Acquisition 14 Pastoral Lease Reform 15 Renewals of Pastoral Leases 15 Role of Land Councils 18 Overview 18 Northern Territory 18 Queensland 18 Western Australia 19 Land Use Agreements 20 Mining Tenures and Income from Mining on Indigenous Land 22 Mining Tenures 22 Mining Income 24 2 MODULE 3 land information Introduction Module 3 describes the rights and obligations of Indigenous land holders in the northern Australia pastoral industry. Indigenous land tenure is administered differently in the Northern Territory (NT), Queensland (Qld) and Western Australia (WA) which has resulted in a high degree of complexity. In addition, this whole area is undergoing a great deal of change. • In November 2012, the Northern Australia Ministerial Forum (NAMF) initiated a review of land tenure management across northern Australia. -

Asymmetrical Distinctions in Waanyi Kinship Terminology1 Mary Laughren

12 Asymmetrical Distinctions in Waanyi Kinship Terminology1 Mary Laughren Introduction Background Waanyi2 kinship terms map onto an ‘Arandic’ system with distinct encoding of the four logical combinations of maternal and paternal relations in the ascending harmonic (‘grandparent’) generation: 1 Without the generous collaboration of the late Mr Roy Seccin Kamarrangi, who valiantly attempted to teach me Waanyi between 2000 and 2005, this study would not have begun. I also acknowledge the assistance received from the late Mr Eric King Balyarrinyi and his companions at the Doomadgee nursing home. I am indebted to Gavan Breen, who shared his Waanyi field notes and insights with me, and to John Dymock, who gave me copies of his vast corpus of Waanyi vocabulary. Thank you to the two anonymous reviewers, whose input to the development of this chapter was substantial, and to Barry Alpher, who provided invaluable feedback on an earlier draft. Errors of fact or interpretation remain my responsibility. The research on Waanyi was supported by a number of small ARC grants through the University of Queensland and the Waanyi Nation Aboriginal Corporation. 2 Waanyi was traditionally spoken in land watered by the upper branches of the Nicholson River and its tributaries, which straddles the Queensland–Northern Territory border to the south of the Gulf of Carpentaria (see Tindale 1974; Trigger 1982). The most closely related language is Garrwa (Breen 2003; Mushin 2012), spoken to the immediate north of Waanyi. The Garrwa-Waanyi language block lies between the northern and southern branches of the Warluwarric language group (Blake 1988, 1990) and is bordered on the east by the Tangkic language Yukulta, also called Ganggalida, (Keen 1983; Nancarrow et al. -

The Blackwords Symposium: the Past, Present, and Future of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Literature

The BlackWords Symposium: The Past, Present, and Future of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Literature KERRY KILNER University of Queensland PETER MINTER University of Sydney We write to create, to survive, and to revolutionise; we write to haunt and we ache because we refuse to leave the past alone. We aim to disrupt the State’s founding order of things, to disrupt ‘patriarchal white sovereignty’ (Moreton- Robinson), white heteronormativity, and the colonial-continuum of history. (Harkin, herein) The BlackWords Symposium, held in October 2012, celebrated the fifth anniversary of the establishment of BlackWords, the AustLit-supported project recording information about, and research into, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers and storytellers. The symposium showcased the exciting state of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander creative writing and storytelling across all forms, contemporary scholarship on Indigenous writing, alongside programs such as the State Library of Queensland’s black&write! project, which supports writers’ fellowships, editing mentorships, and a trainee editor program for professional development for Indigenous editors. But really, the event was a celebration of the sort of thinking, the sort of resistance, and the re-writing of history that is evident in the epigraph to this introduction. The speakers, who included Melissa Lucashenko, Wesley Enoch, Sandra Phillips, Ellen Van Neerven, Jeanine Leane, and Boori Pryor alongside the authors of the works in this collection, explored a diverse range of topics -

Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia

Recirculating songs: Revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (editors) Although song has been recognised as the ‘central repository of Aboriginal knowledge’, this is the first volume to be devoted specifically to the revitalisation of ancestral Indigenous singing practices. These traditions are at severe risk of attrition or loss in many parts of Australia, and the 17 chapters of the present work provide broad coverage – geographically, theoretically and methodologically – of the various strategies that are currently being implemented or proposed to reverse this damage to the Indigenous knowledge base. In some communities the ancestral musical culture is still being transmitted across generations; in others it is partially remembered, and being revitalised with the assistance of heritage recordings and written documentation; but in many parts of Australia, intergenerational transmission has been interrupted, and in these cases, revitalisation depends on research and restoration. This book provides insights that may be helpful for Indigenous people and communities, and the researchers and educators who work with them, across this range of contexts. Cover photograph ulpare-ulpare (Arrernte) ‘Perennial Yellowtop’ (Senecio magnificus) © Lisa Stefanoff Cover song by M. K. Turner. Transcriptions (text and music) by Myfany Turpin. Kwarre-arle ayenge antyeye-le atyenge-ange tne-me girl-REL 1SG.NOM alongside-LOC 1sg.ACC-CNTR stand-PRS ‘The girl who I am is standing with me.’ Front cover: an Arrernte women’s song received, sung and translated by M. K. Turner (‘MK’) in 2017. The song conveys two images for MK: a group of girls standing in a line proudly adorned for ceremony; and a girl walking through the grass where ankerte-ankerte ‘yellow daisies’ and arlatyeye ‘white pencil yam flowers’ bloom. -

150718-TH.M-4-In the Beginning Was the Dream

Alluring (Clockwise from left) ‘Untitled’ by William Barak; 'Red Plains Kangaroo' by Yirawala; 'Bush Plum Country' by Poly Ngal. National Gallery of Australia innocence comes apart when we look closer. William Barak (1824-1903) belonged to the Wu- rundjeri/ Woiwurung peoples, of Port Phillip. His work bridges the divide between the tradi- tional and the contemporary. He moves away from the traditional geometric patterns in the work of the Aboriginals that did not depict humans, but were a means to seize the animal spirit. In Barak’s painting ‘Corrobo- ree’ we have people of cooler regions, dressed in Possum skin cloaks. Barak was a child when Eu- ropeans began to make incursions into Port Phil- lip and he represents the transition of cultures in his works. The Europeans referred to him as the ‘last chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe.’ Three sisters The video room has works of the Bidjara artist, Christian Thompson. Three large monitors at the centre show three women of mixed ancestry. An off-screen fan blows their hair and they are bathed in a yellow light. The idea is that they are in the Queensland desert, buffeted by its arid winds. A lilting piece of music — hypnotic, calm- ing and sensuous — accompanies the images. I learn that the three are not just any women — they are three sisters whose grandfather is Char- SPOTLIGHT lie Perkins, the first Aboriginal person to gain a degree and become a permanent head of federal government. His parents were of mixed blood. His daughter, Hetti Perkins, is an influential cura- tor. -

Kerwin 2006 01Thesis.Pdf (8.983Mb)

Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author Kerwin, Dale Wayne Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1614 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366276 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author: Dale Kerwin Dip.Ed. P.G.App.Sci/Mus. M.Phil.FMC Supervised by: Dr. Regina Ganter Dr. Fiona Paisley This dissertation was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts at Griffith University. Date submitted: January 2006 The work in this study has never previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any University and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this study contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the study itself. Signed Dated i Acknowledgements I dedicate this work to the memory of my Grandfather Charlie Leon, 20/06/1900– 1972 who took a group of Aboriginal dancers around the state of New South Wales in 1928 and donated half their gate takings to hospitals at each town they performed. Without the encouragement of the following people this thesis would not be possible. To Rosy Crisp, who fought her own battle with cancer and lost; she was my line manager while I was employed at (DATSIP) and was an inspiration to me. -

Agricultural Sleeper Weeds in Australia

Funded by Land and Water Australia, CSIRO and JCU i ii An Assessment of the Social and Economic Values of Australia’s Tropical Rivers Scoping report prepared for Land and Water Australia’s Tropical Rivers Program September 2006 Natalie Stoeckl#, Owen Stanley#, Sue Jackson*, Anna Straton* and Vicki Brown# Funded by Land and Water Australia, CSIRO and JCU # School of Business, James Cook University * CSIRO iii Acknowledgements Special thanks go to Romy Greiner and Dan Walker for their contributions in setting up the framework for this study. We would also like to thank the Northern Australia Irrigation Futures team (Patrick Hegarty, Bart Kellett, Cuan Petheram and Keith Bristow) for allowing us to use much of their work on the laws, programs and institutions affecting water use in the TR region. Many thanks also to Danielle Brooker, Melanie Giannikos and Karina Lynch for their research assistance, and to Alexander Herr and Wolfgang Stoeckl for their GIS contributions. We would also like to acknowledge the very special contribution made by the many people who assisted with the organisation and promotion of the community forums: Barbara McKaige (CSE), Emma Woodward (CSE), Patrick O’Leary (CSE), Anna Mardling and Charles Prouse (Kimberley Land Council), Madonna McKay (Katherine region NRM facilitator), Clare Taylor (Rivercare). Finally – and perhaps most importantly – we thank all of those who participated in community forums. iv Executive summary Background Covering an area of more than 1.3 million km2, the tropical rivers (TR) region includes 55 river basins and extends across all catchments from the west side of Cape York to the Kimberley, through Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia. -

Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation Patrick Mcconvell

1 Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation Patrick McConvell This volume presents papers written about Aboriginal Australia for the AustKin project. By way of definition, ‘kin’ refers to kinship terminology and systems, and related matters of marriage and other behaviour; and ‘skin’ refers to what is also known as ‘social categories’ and what earlier anthropologists (e.g. Fison & Howitt 1880) called ‘social organisation’: moieties, sections, subsections and other similar categories. Kinship terms are ‘egocentric’ in anthropological parlance and skin terms are ‘sociocentric’. Different kinship terms are used depending on the ego (propositus) and who is being referred to. Conversely, skin terms are a property of the person being referred to and the category to which he or she belongs— not of their relationship to someone else. However, membership of a skin category does imply a kinship relationship. For example, I was assigned the skin (subsection) name Jampijina by the Gurindji, which means that I am classified as brother (kinship term papa) to other people of Jampijina skin, father to Jangala and Nangala, and so on. Additionally, a ‘clan’, known as a ‘local descent group’, is a group rather than a category such as a skin. Namely, it is a group of people who have common rights and interests in property, which may be intellectual property or, importantly, tracts of land. These rights and interests are generally inherited by descent, from fathers and/or mothers and more distant ancestors (although rights can be transmitted in other ways). 1 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN By contrast, people of a skin category are not collective owners of anything: for example, the people of the Jampijina subsection do not have common rights and interests in land. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

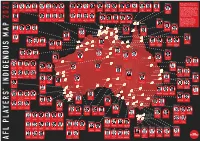

2021 Indigenous Player

Larrakia Kija Tiwi Malak Malak Warray Jawoyn Warramungu Waiben Island Meriam Mir NB: Player images may appear twice as players have provided information for multiple language and/or cultural groups. DISCLAIMER : This map indicates only the general location of larger groupings of Mia King people, which may include smaller groups Trent Burgoyne Steven May Steven Motlop Brandan Parfitt Jy Farrar Liam Jones Shane McAdam Mikayla Morrison Janet Baird Ben Long Sean Lemmens Anthony McDonald- Ben Long Shaun Burgoyne Trent Burgoyne Keidean Coleman Blake Coleman Jed Anderson Brandan Parfitt Ben Davis ST KILDA HAWTHORN PORT BRISBANE BRISBANE NORTH NORTH GEELONG ADELAIDE such as clans, dialects or individual PORT MELBOURNE PORT ADELAIDE GEELONG GOLD COAST CARLTON ADELAIDE FREMANTLE GOLD COAST ST KILDA GOLD COAST Tipungwuti MELBOURNE ADELAIDE ESSENDON ADELAIDE MELBOURNE Alicia Janz languages in a group. Boundaries are not WEST COAST intended to be exact. For more detailed EAGLES Iwaidja Dalabon information about the groups of people in a particular region contact the relevant land council. Not suitable for use in native title and other land claims. Names and regions as used in the Yupangathi Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia Stephanie Williams Irving Mosquito Krstel Petrevski Sam Petrevski-Seton Leno Thomas Danielle Ponter Daniel Rioli Willie Rioli Maurice Rioli Jnr GEELONG ESSENDON MELBOURNE CARLTON FREMANTLE ADELAIDE RICHMOND WEST COAST RICHMOND Waiben (D. Horton, General Editor) published EAGLES Janet Baird Nakia Cockatoo Stephanie Williams Keidean Coleman Blake Coleman Island Yirrganydji in 1994 by the Australian Institute of GOLD COAST BRISBANE GEELONG BRISBANE BRISBANE Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Meriam Mìr Studies (Aboriginal Studies Press) Jaru Kuku-Yalanji GPO Box 553 Canberra, Act 2601.