Ecological Status of Kali River Flood Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Badis Britzi, a New Percomorph Fish (Teleostei: Badidae) from the Western Ghats of India

Zootaxa 3941 (3): 429–436 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3941.3.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A4916102-7DF3-46D8-98FF-4C83942C63C9 Badis britzi, a new percomorph fish (Teleostei: Badidae) from the Western Ghats of India NEELESH DAHANUKAR1,2, PRADEEP KUMKAR3, UNMESH KATWATE4 & RAJEEV RAGHAVAN2,5, 6 1Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, G1 Block, Dr. Homi Bhabha Road, Pashan, Pune 411 008, India 2Systematics, Ecology and Conservation Laboratory, Zoo Outreach Organization, 96 Kumudham Nagar, Vilankurichi Road, Coim- batore, Tamil Nadu 641 035, India 3Department of Zoology, Modern College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411 016, India 4Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), Hornbill House, Opp. Lion Gate, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Road, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400 001, India 5Conservation Research Group (CRG), Department of Fisheries, St. Albert’s College, Kochi, Kerala 682 018, India 6Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Badis britzi, the first species of the genus endemic to southern India, is described from the Nagodi tributary of the west- flowing Sharavati River in Karnataka. It is distinguished from congeners by a combination of characters including a slen- der body, 21–24 pored lateral-line scales and a striking colour pattern consisting of 11 bars and a mosaic of black and red pigmentation on the side of the body including the end of caudal peduncle, and the absence of cleithral, opercular, or cau- dal-peduncle blotches, or an ocellus on the caudal-fin base. -

LIST of INDIAN CITIES on RIVERS (India)

List of important cities on river (India) The following is a list of the cities in India through which major rivers flow. S.No. City River State 1 Gangakhed Godavari Maharashtra 2 Agra Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 3 Ahmedabad Sabarmati Gujarat 4 At the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and Allahabad Uttar Pradesh Saraswati 5 Ayodhya Sarayu Uttar Pradesh 6 Badrinath Alaknanda Uttarakhand 7 Banki Mahanadi Odisha 8 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 9 Baranagar Ganges West Bengal 10 Brahmapur Rushikulya Odisha 11 Chhatrapur Rushikulya Odisha 12 Bhagalpur Ganges Bihar 13 Kolkata Hooghly West Bengal 14 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 15 New Delhi Yamuna Delhi 16 Dibrugarh Brahmaputra Assam 17 Deesa Banas Gujarat 18 Ferozpur Sutlej Punjab 19 Guwahati Brahmaputra Assam 20 Haridwar Ganges Uttarakhand 21 Hyderabad Musi Telangana 22 Jabalpur Narmada Madhya Pradesh 23 Kanpur Ganges Uttar Pradesh 24 Kota Chambal Rajasthan 25 Jammu Tawi Jammu & Kashmir 26 Jaunpur Gomti Uttar Pradesh 27 Patna Ganges Bihar 28 Rajahmundry Godavari Andhra Pradesh 29 Srinagar Jhelum Jammu & Kashmir 30 Surat Tapi Gujarat 31 Varanasi Ganges Uttar Pradesh 32 Vijayawada Krishna Andhra Pradesh 33 Vadodara Vishwamitri Gujarat 1 Source – Wikipedia S.No. City River State 34 Mathura Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 35 Modasa Mazum Gujarat 36 Mirzapur Ganga Uttar Pradesh 37 Morbi Machchu Gujarat 38 Auraiya Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 39 Etawah Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 40 Bangalore Vrishabhavathi Karnataka 41 Farrukhabad Ganges Uttar Pradesh 42 Rangpo Teesta Sikkim 43 Rajkot Aji Gujarat 44 Gaya Falgu (Neeranjana) Bihar 45 Fatehgarh Ganges -

Ecological Status of Kali River Flood Plain

Annexure 6 Ecological Status of Kali River Flood Plain Sahyadri Conservation Series: 8 ENVIS Technical Report: 29, October 2008 Environmental Information System [ENVIS] Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore - 560012, INDIA Web: http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/hpg/envis http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy/ http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/biodiversity Email: [email protected], [email protected] 102 Ecological Status of Kali River Flood Plain Sr. No. Title Page No. 1 Summary 3 2 Introduction 6 3 Study area 15 4 Methods 21 5 Result and Discussion 23 6 Conclusion 49 7 Acknowledgment 49 8 References 50 Tables Sr.No Name Pg No. 1 List of organisms found in Western Ghats with their endemism percentage 8 2 Acts and policies in India for protecting environment and wildlife 11 3 Land use details in the drainage basin of River Kali 16 4 Shrubs of Kali flood plain 24 5 Herbs of Kali flood plain 24 6 Trees of Kali flood plain 26 7 Climbers of Kali flood plain 28 8 Ferns of Kali flood plain 28 9 Rare and Threatened plants of Kali flood plain 28 10 The water quality values for each month during the study period in Naithihole 33 11 The water quality values for each month during the study period in Sakthihalla 34 12 Amphibian species list recorded from Kali River Catchment 36 13 Birds of Kali River Flood Plains 38 14 Water birds of the study area 40 Figures Sr.No Title Sr. No. Page No. 1 Study area – The flood plains of Kali River 17 2 Drainage network in Kali River basin 18 3 Mean Annual Rainfall in Kali River Basin 18 4 Land -

Dams-In-India-Cover.Pdf

List of Dams in India List of Dams in India ANDHRA PRADESH Nizam Sagar Dam Manjira Somasila Dam Pennar Srisailam Dam Krishna Singur Dam Manjira Ramagundam Dam Godavari Dummaguden Dam Godavari ARUNACHAL PRADESH Nagi Dam Nagi BIHAR Nagi Dam Nagi CHHATTISGARH Minimata (Hasdeo) Bango Dam Hasdeo GUJARAT Ukai Dam Tapti Dharoi Sabarmati river Kadana Mahi Dantiwada West Banas River HIMACHAL PRADESH Pandoh Beas Bhakra Nangal Sutlej Nathpa Jhakri Dam Sutlej Chamera Dam Ravi Pong Dam Beas https://www.bankexamstoday.com/ Page 1 List of Dams in India J & K Bagihar Dam Chenab Dumkhar Dam Indus Uri Dam Jhelam Pakal Dul Dam Marusudar JHARKHAND Maithon Dam Maithon Chandil Dam Subarnarekha River Konar Dam Konar Panchet Dam Damodar Tenughat Dam Damodar Tilaiya Dam Barakar River KARNATAKA Linganamakki Dam Sharavathi river Kadra Dam Kalinadi River Supa Dam Kalinadi Krishna Raja Sagara Dam Kaveri Harangi Dam Harangi Narayanpur Dam Krishna River Kodasalli Dam Kali River Basava Sagara Krishna River Tunga Bhadra Dam Tungabhadra River, Alamatti Dam Krishna River KERALA Malampuzha Dam Malampuzha River Peechi Dam Manali River Idukki Dam Periyar River Kundala Dam Parambikulam Dam Parambikulam River Walayar Dam Walayar River https://www.bankexamstoday.com/ Page 2 List of Dams in India Mullaperiyar Dam Periyar River Neyyar Dam Neyyar River MADHYA PRADESH Rajghat Dam Betwa River Barna Dam Barna River Bargi Dam Narmada River Bansagar Dam Sone River Gandhi Sagar Dam Chambal River . Indira Sagar Narmada River MAHARASHTRA Yeldari Dam Purna river Ujjani Dam Bhima River Mulshi -

Fruit Preferences of Malabar Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros Coronatus in Western Ghats, India

Bird Conservation International (2004) 14:S69–S79. BirdLife International 2004 doi:10.1017/S0959270905000249 Printed in the United Kingdom Fruit preferences of Malabar Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros coronatus in Western Ghats, India P. BALASUBRAMANIAN, R. SARAVANAN and B. MAHESWARAN Summary Food habits of Malabar Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros coronatus were studied from December 2000 to December 2001, in the Athikadavu valley, Western Ghats, India. A total of 147 individuals belonging to 18 fleshy-fruited tree species were monitored fortnightly. Thirteen fruit species, including five figs and eight non-figs, were recorded in the birds’ diet. The overall number of tree species in fruit and fruiting individuals increased with the onset of summer, the Malabar Pied Hornbill’s breeding season. The peak in fruiting is attributed to the peak in fruiting by figs. Figs formed the top three preferred food species throughout the year. During the non-breeding period (May to February), 60% of the diet was figs. During the peak breeding period (March and April), two nests were monitored for 150 hours. Ninety-eight per cent of food deliveries to nest inmates were fruits belong- ing to six species. Most fruits delivered at the nests constituted figs (75.6%). In addition, figs sustained hornbills during the lean season and should be considered “keystone species” in the riverine forest ecosystem. Two non-fig species are also important. Habitat features and local threats at Athikadavu valley were assessed. The distribution and conservation status of Malabar Pied Hornbill in the Western Ghats was reviewed. Conser- vation of hornbill habitats, particularly the lowland riparian vegetation, is imperative. -

A1 SYSTEM MAP 2021.Cdr

TO TO PUNE (PA) LATUR TO Eó®Ò¨ÉxÉMÉ® TO NANDED ROHA 0.000, 191.590(CST) DAUND JN.(DD) PARBHANI JN. ÊxÉVÉɨÉɤÉÉn 267.180(CST) KARIMNAGAR TO ENLARGEMENT AT A C NIZAMABAD MUMBAI ENLARGEMENT AT =º¨ÉÉxÉɤÉÉn HOSAPETE JN. (HPT) 143.261, 0.000(AVC) TORANAGALLU JN. (TNGL) NH 7 BAYALU VODDIGERI OSMANABAD 141.798 (BYO)161.530 175.700, 0.000(RNJP) MARMAGAO HARBOUR TO TO PAPINAYAKANAHALLI (MRH) 111.870 BALLARI CANTT. KURDUWADI JN. (KWV) MIRAJ HUBBALLI JN. (PKL)156.510 DAROJI (BYC) 202.940 376.28(CST) GADIGANURU (DAJ) 181.270 KONKAN RAILWAY MUNIRABAD (MRB) 137.290 (GNR)168.470 BELLARY CANTONMENT (H) VASCO-DA-GAMA 204.100 BARAMATI TO HOSAPETE BYE PASS LINE INDIA (VSG) 108.458 2.510 310.880(CST) KAZIPET JN. BALLARI JN. (BAY) TUNGA BHADRA DAM (TBDM) 5.020 KUDATINI 208.060, 0.000(RDG) KARIGANURU (KDN)188.230 DABOLIM (H) SWR LIMIT XX VERNA (KGW)149.605 174.105 KHED (DBM) 103.384 VYASANAKERI (VYS) 10.300 ºÉiÉÉ®É BIDAR (BIDR) TORANAGALLU 1.658 212.000 SOLAPUR (SUR) ¨ÉänE SWR LIMIT VYASA COLONY JN(VC) NH 9 ¤ÉÒn® 90.780 92.500 BYE PASS LINE TO BHIMA 454.970, 299.440(GDG) 16.218,0.000(SMLI) BALLARI SATARA SANKAVAL GUNTAKAL JN. XX RIVER MEDAK SWR LIMIT MAJORDA JN. (MJO) GUNJI (GNJ) MARIYAMMANAHALLI (H) (MMI) 21.930 BANNIHATTI BYE PASS LINE BIDAR XX (SKVL) 100.391 572.990 ¶ÉÉä±ÉÉ{ÉÖ® XX 109.110 (BNHT) 9.020 HOTGI JN. (HG) 435.730(ROHA/KRCL) HAMPAPATNAM (H) RAMGAD HADDINAGUNDU XX NH 9 470.040, 284.090(GDG) 91.500(LD) (HPM) 33.170 (RMGD) 13.122 (HDD) 214.680 SOLAPUR CANSAULIM TINAIGHAT TO OBALAPURAM CHIPLUN SWR LIMIT SANJUJE- DA- AREYAL (H) 0 (CSM) 95.873 (TGT) 11.640 HUBBALLI YESHWANTH NAGAR (OBM) 15.40 281.900 HUMNABAD XX (SJDA)79.655 SULERJAVALGE (H) (SLGE) 271.520 CASTLEROCK (YTG) 23.992 TPURA XX VALI (H) (SRVX) RANJI RAM (HMBD) 37.207 SURA (CLR) 24.500 HAGARIBOMMANAHALLI SOMALAPU 439.020, 88.210(LD) (RNJP) 23.020 30.860 TADWAL (TVL) 264.180 (HBI) 43.470 (SLM) SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY Eó±É¤ÉÙ®MÉÒ SECUNDERABAD JN. -

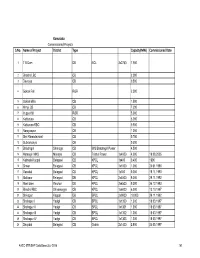

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 1 T B Dam DB NCL 3x2750 7.950 2 Bhadra LBC CB 2.000 3 Devraya CB 0.500 4 Gokak Fall ROR 2.500 5 Gokak Mills CB 1.500 6 Himpi CB CB 7.200 7 Iruppu fall ROR 5.000 8 Kattepura CB 5.000 9 Kattepura RBC CB 0.500 10 Narayanpur CB 1.200 11 Shri Ramadevaral CB 0.750 12 Subramanya CB 0.500 13 Bhadragiri Shimoga CB M/S Bhadragiri Power 4.500 14 Hemagiri MHS Mandya CB Trishul Power 1x4000 4.000 19.08.2005 15 Kalmala-Koppal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x400 0.400 1990 16 Sirwar Belagavi CB KPCL 1x1000 1.000 24.01.1990 17 Ganekal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x350 0.350 19.11.1993 18 Mallapur Belagavi DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 29.11.1992 19 Mani dam Raichur DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 24.12.1993 20 Bhadra RBC Shivamogga CB KPCL 1x6000 6.000 13.10.1997 21 Shivapur Koppal DB BPCL 2x9000 18.000 29.11.1992 22 Shahapur I Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1300 1.300 18.03.1997 23 Shahapur II Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1301 1.300 18.03.1997 24 Shahapur III Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1302 1.300 18.03.1997 25 Shahapur IV Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1303 1.300 18.03.1997 26 Dhupdal Belagavi CB Gokak 2x1400 2.800 04.05.1997 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 141 S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 27 Anwari Shivamogga CB Dandeli Steel 2x750 1.500 04.05.1997 28 Chunchankatte Mysore ROR Graphite India 2x9000 18.000 13.10.1997 Karnataka State 29 Elaneer ROR Council for Science and 1x200 0.200 01.01.2005 Technology 30 Attihalla Mandya CB Yuken 1x350 0.350 03.07.1998 31 Shiva Mandya CB Cauvery 1x3000 3.000 10.09.1998 -

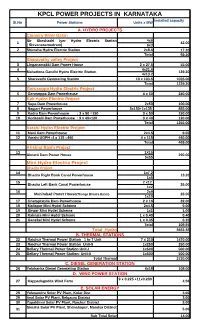

KPCL POWER PROJECTS in KARNATAKA Installed Capacity Sl.No Power Stations Units X MW

KPCL POWER PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA Installed capacity Sl.No Power Stations Units x MW A. HYDRO PROJECTS Cauvery River Basin Sir Sheshadri Iyer Hydro Electric Station 4x6 1 42.00 ( Shivanasamudram) 6x3 2 Shimsha Hydro Electric Station 2x8.6 17.20 Total 59.20 Sharavathy valley Project 3 Linganamakki Dam Power House 2 x 27.5 55.00 4 4x21.6 Mahathma Gandhi Hydro Electric Station 139.20 4x13.2 5 Sharavathi Generating Station 10 x 103.5 1035.00 Total 1229.20 Gerusoppa Hydro Electric Project 6 Gerusoppa Dam Powerhouse 4 x 60 240.00 Kali Hydro Electric Project 7 Supa Dam Powerhouse 2x50 100.00 8 Nagjari Powerhouse 5x150+1x135 885.00 9 Kadra Dam Powerhouse : 3 x 50 =150 3 x 50 150.00 10 Kodasalli Dam Powerhouse : 3 x 40=120 3 x 40 120.00 Total 1255.00 Varahi Hydro Electric Project 11 Mani Dam Powerhouse 2x4.5 9.00 12 Varahi UGPH :4 x 115 =460 4 x 115 460.00 Total 469.00 Krishna Basin Project 13 1X15 Almatti Dam Power House 290.00 5x55 Mini Hydro Electric Project Bhadra Project 14 1x7.2 Bhadra Right Bank Canal Powerhouse 13.20 1x6 15 2 x12 Bhadra Left Bank Canal Powerhouse 26.00 1x2 16 2x9 Munirabad Power House(Thunga Bhadra Basin) 28.00 1x10 17 Ghataprabha Dam Powerhouse 2 x 16 32.00 18 Mallapur Mini Hydel Scheme 2x4.5 9.00 19 Sirwar Mini Hydel Scheme 1x1 1.00 20 Kalmala Mini Hydel Scheme 1 x 0.40 0.40 21 Ganekal Mini Hydel Scheme 1 x 0.35 0.35 Total 109.95 Total Hydro 3652.35 B. -

Oriental Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros Albirostris Hunts an Adult Common Myna Acridotheres Tristis

Correspondence 119 Kemp, A. C., & Boesman, P., 2018. Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., & de Juana, E., (eds.). Handbook Correspondence of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (Accessed from https:// www.hbw.com/node/55904 on 13 May 2018). Oriental Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros albirostris hunts Poonswad, P., Tsuji, A., & Ngampongsai, C., 1986. A comparative ecological study of an adult Common Myna Acridotheres tristis four sympatric hornbills (Family Bucerotidae) in Thailand. Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornthologici. Vol. II: June 22–29, 1986, Ottawa, Canada. University The Oriental Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros albirostris is a frequent of Ottawa Press. visitor to the city of Dehradun (30.3165°N, 78.0322°E), Primrose, A. M., 1921. Notes on the “Habits of Anthracoceros albirostris, the Indo- Uttarakhand, which is surrounded by moist deciduous forest. In Burmese Pied Hornbill, in confinement.” Journal of the Bombay Natural History large campuses with good green cover, like the Forest Research Society 27 (4): 950–951. Institute (henceforth, FRI) and the Wildlife Institute of India, a few – Naman Goyal & Akanksha Saxena pairs have been recorded as year-round residents. Wildlife Institute of India, PO Box 18 Chandrabani, Dehradun 248001, Uttarakhand, India. E-mail: [email protected] On 01 June 2013 at 1500 hrs we saw a flock of adult Common Mynas Acridotheres tristis perching on a sandalwood Santalum album tree in the FRI campus. Shortly, a single male Noteworthy records from Virajpet, Kodagu District, Oriental Pied Hornbill flew into the flock, grabbed a myna by its Karnataka neck, and carried it off to another tree. -

Karwar F-Register As on 31-03-2019

Karwar F-Register as on 31-03-2019 Type of Name of Organisat Date of Present Registrati Year of Category Applicabi Applicabi Registration Area / the ion / Size Colour establish Capital Working on under E- Sl. Identifica Name of the Address of the No. (XGN lity under Water Act lity under Air Act HWM HWM BMW BMW under Plastic Battery E-Waste MSW MSW PCB ID Place / Taluk District industrial Activity*( Product (L/M/S/M (R/O/G/ ment Investment in Status Plastic Waste Remarks No. tion (YY- Industry Organisations category Water (Validity) Air Act (Validity) (Y/N) (Validity) (Y/N) (Validity) Rules validity (Y/N) (Validity) (Y/N) (Validity) Ward No. Estates / I/M/LB/H icro) W) (DD/MM/ Lakhs of Rs. (O/C1/C2 Rules (Y/N) YY) Code) Act (Y/N) (Y/N) date areas C/H/L/C YY) /Y)** (Y/N) E/C/O Nuclear Power Corporation Limited, 31,71,29,53,978 1 11410 99-00 Kaiga Project Karwar Karwar Uttar Kannada NA I Nuclear Power plant F-36 L R 02-04-99 O Y 30-06-21 Y 30-06-21 Y 30/06/20 N - N N N N N N N Kaiga Generating (576450.1) Station, Grasim Industries Limited Chemical Binaga, Karwar, 2 11403 74-75 Division (Aditya Karwar Karwar Uttar Kannada NA I Chloro Alkali F-41, 17-Cat 17-Cat 01-01-75 18647.6 O Y 30-06-21 Y 30-06-21 Y 30/06/20 Y - N N N N N N N Uttara Kannada Birla Chemical Dividion) Bangur The West Coast Nagar,Dandeli, 3 11383 58-59 Haliyal Haliyal Uttar Kannada NA I Paper F-59, 17-Cat 17-Cat 01-06-58 192226.1 O Y 30-06-21 Y 30-06-21 Y 30/06/20 Y - N N NNNNN Paper Mills Limited, Haliyal, Uttara Kannada R.N.S.Yatri Niwas, Murudeshwar, (Formerly R N 4 41815 -

6. Water Quality ------61 6.1 Surface Water Quality Observations ------61 6.2 Ground Water Quality Observations ------62 7

Version 2.0 Krishna Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. The practice of basin planning has developed due to the changing demands on river systems and the changing conditions of rivers by human interventions. -

Original Research Article POLLINATION ECOLOGY AND

1 Original Research Article POLLINATION ECOLOGY AND FRUITING BEHAVIOUR IN STRYCHNOS NUX-VOMICAL. (LOGANIACEAE) ABSTRACT Aims: Strychnosnux-vomica is a valuable drug plants. Knowledge on its breeding system and pollination ecology will assist future research on genetic improvement for higher yield attributes. Place and Duration of Study: The study was conducted in the Silvicultural Research Station, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India between 2016-2018 Methodology: Pollination experiment was conducted for autogamy, geitonogamy, xenogamy, apomixis and open pollination by allocating three hundred flowers for each experiment. Phenological events, pollinator visit and their behaviour were recorded at regular intervals. Results: Pollination studies in Strychnos nux-vomica revealed mixed mating system in its flowers. Flowers are small, greenish-white, bisexual, nectariferous and emit mild sweet odour. They open during evening hours and offer pollen and nectar to the visitors. Bees, flies, wasps, butterflies, beetles and birds are the pollinators. Apis dorsata and Euploea core are the principal one and makes diurnal visit between 7.00-17.00 hours. The anther dehiscence starts at 16.00-16.15 hours. The capitate stigma receptive to pollen germination at 17.30-18.00 hours and remain in receptive state one day after complete anther dehiscence. Flowers favour cross-pollination (29.78-60.26%) however selfing is also possible (17.94-39.74%). Conclusion: Information on breeding system and pollination ecology will be helpful in developing a breeding strategy for higher fruit set and seed yield. KEYWORDS: Reproductive Biology, Breeding System, Medicinal Plant, Strychnine, Brucine INTRODUCTION Strychnosnux-vomica L. is a source of poisonous alkaloids strychnine, brucine and their derivatives [1].