Limiting Neuronal Nogo Receptor 1 Signaling During Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Preserves Axonal Transport and Abrogates Inflammatory Demyelination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Table S1

Entrez Gene Symbol Gene Name Affymetrix EST Glomchip SAGE Stanford Literature HPA confirmed Gene ID Profiling profiling Profiling Profiling array profiling confirmed 1 2 A2M alpha-2-macroglobulin 0 0 0 1 0 2 10347 ABCA7 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 7 1 0 0 0 0 3 10350 ABCA9 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 9 1 0 0 0 0 4 10057 ABCC5 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 5 1 0 0 0 0 5 10060 ABCC9 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 9 1 0 0 0 0 6 79575 ABHD8 abhydrolase domain containing 8 1 0 0 0 0 7 51225 ABI3 ABI gene family, member 3 1 0 1 0 0 8 29 ABR active BCR-related gene 1 0 0 0 0 9 25841 ABTB2 ankyrin repeat and BTB (POZ) domain containing 2 1 0 1 0 0 10 30 ACAA1 acetyl-Coenzyme A acyltransferase 1 (peroxisomal 3-oxoacyl-Coenzyme A thiol 0 1 0 0 0 11 43 ACHE acetylcholinesterase (Yt blood group) 1 0 0 0 0 12 58 ACTA1 actin, alpha 1, skeletal muscle 0 1 0 0 0 13 60 ACTB actin, beta 01000 1 14 71 ACTG1 actin, gamma 1 0 1 0 0 0 15 81 ACTN4 actinin, alpha 4 0 0 1 1 1 10700177 16 10096 ACTR3 ARP3 actin-related protein 3 homolog (yeast) 0 1 0 0 0 17 94 ACVRL1 activin A receptor type II-like 1 1 0 1 0 0 18 8038 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 1 0 0 0 0 19 8751 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 1 0 0 0 0 20 8728 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 1 0 0 0 0 21 81792 ADAMTS12 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 12 1 0 0 0 0 22 9507 ADAMTS4 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Actin Nucleator Spire 1 Is a Regulator of Ectoplasmic Specialization in the Testis Qing Wen1,Nanli1,Xiangxiao 1,2,Wing-Yeelui3, Darren S

Wen et al. Cell Death and Disease (2018) 9:208 DOI 10.1038/s41419-017-0201-6 Cell Death & Disease ARTICLE Open Access Actin nucleator Spire 1 is a regulator of ectoplasmic specialization in the testis Qing Wen1,NanLi1,XiangXiao 1,2,Wing-yeeLui3, Darren S. Chu1, Chris K. C. Wong4, Qingquan Lian5,RenshanGe5, Will M. Lee3, Bruno Silvestrini6 and C. Yan Cheng 1 Abstract Germ cell differentiation during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis is accompanied by extensive remodeling at the Sertoli cell–cell and Sertoli cell–spermatid interface to accommodate the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes and developing spermatids across the blood–testis barrier (BTB) and the adluminal compartment of the seminiferous epithelium, respectively. The unique cell junction in the testis is the actin-rich ectoplasmic specialization (ES) designated basal ES at the Sertoli cell–cell interface, and the apical ES at the Sertoli–spermatid interface. Since ES dynamics (i.e., disassembly, reassembly and stabilization) are supported by actin microfilaments, which rapidly converts between their bundled and unbundled/branched configuration to confer plasticity to the ES, it is logical to speculate that actin nucleation proteins play a crucial role to ES dynamics. Herein, we reported findings that Spire 1, an actin nucleator known to polymerize actins into long stretches of linear microfilaments in cells, is an important regulator of ES dynamics. Its knockdown by RNAi in Sertoli cells cultured in vitro was found to impede the Sertoli cell tight junction (TJ)-permeability barrier through changes in the organization of F-actin across Sertoli cell cytosol. Unexpectedly, Spire 1 knockdown also perturbed microtubule (MT) organization in Sertoli cells cultured in vitro. -

Applying Expression Profile Similarity for Discovery of Patient-Specific

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/172015; this version posted September 17, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Applying expression profile similarity for discovery of patient-specific functional mutations Guofeng Meng Partner Institute of Computational Biology, Yueyang 333, Shanghai, China email: [email protected] Abstract The progress of cancer genome sequencing projects yields unprecedented information of mutations for numerous patients. However, the complexity of mutation profiles of patients hinders the further understanding of mechanisms of oncogenesis. One basic question is how to uncover mutations with functional impacts. In this work, we introduce a computational method to predict functional somatic mutations for each of patient by integrating mutation recurrence with similarity of expression profiles of patients. With this method, the functional mutations are determined by checking the mutation enrichment among a group of patients with similar expression profiles. We applied this method to three cancer types and identified the functional mutations. Comparison of the predictions for three cancer types suggested that most of the functional mutations were cancer-type-specific with one exception to p53. By checking prediction results, we found that our method effectively filtered non-functional mutations resulting from large protein sizes. In addition, this methods can also perform functional annotation to each patient to describe their association with signalling pathways or biological processes. In breast cancer, we predicted "cell adhesion" and other mutated gene associated terms to be significantly enriched among patients. -

Functions of Nogo Proteins and Their Receptors in the Nervous System

REVIEWS Functions of Nogo proteins and their receptors in the nervous system Martin E. Schwab Abstract | The membrane protein Nogo-A was initially characterized as a CNS-specific inhibitor of axonal regeneration. Recent studies have uncovered regulatory roles of Nogo proteins and their receptors — in precursor migration, neurite growth and branching in the developing nervous system — as well as a growth-restricting function during CNS maturation. The function of Nogo in the adult CNS is now understood to be that of a negative regulator of neuronal growth, leading to stabilization of the CNS wiring at the expense of extensive plastic rearrangements and regeneration after injury. In addition, Nogo proteins interact with various intracellular components and may have roles in the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) structure, processing of amyloid precursor protein and cell survival. Nogo proteins were discovered, and have been exten- The amino-terminal segments of the proteins sively studied, in the context of injury and repair of fibre encoded by the different RTN genes have differing tracts in the CNS1 — a topic of great research interest lengths and there is no homology between them3,5. The and clinical relevance. However, much less in known N termini of the RTN4 products Nogo-A and Nogo-B are about the physiological functions of Nogo proteins in identical, consisting of a 172-amino acid sequence that development and in the intact adult organism, including is encoded by a single exon (exon 1) that is followed by in the brain. Through a number of recent publications, a short exon 2 and, in Nogo-A, by the very long exon Nogo proteins have emerged as important regulators of 3 encoding 800 amino acids2,6 (FIG. -

Cldn19 Clic2 Clmp Cln3

NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation When time to diagnosis matters, the NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation from Athena Diagnostics delivers rapid, 5- to 7-day results on a targeted 1,722-genes. A2ML1 ALAD ATM CAV1 CLDN19 CTNS DOCK7 ETFB FOXC2 GLUL HOXC13 JAK3 AAAS ALAS2 ATP1A2 CBL CLIC2 CTRC DOCK8 ETFDH FOXE1 GLYCTK HOXD13 JUP AARS2 ALDH18A1 ATP1A3 CBS CLMP CTSA DOK7 ETHE1 FOXE3 GM2A HPD KANK1 AASS ALDH1A2 ATP2B3 CC2D2A CLN3 CTSD DOLK EVC FOXF1 GMPPA HPGD K ANSL1 ABAT ALDH3A2 ATP5A1 CCDC103 CLN5 CTSK DPAGT1 EVC2 FOXG1 GMPPB HPRT1 KAT6B ABCA12 ALDH4A1 ATP5E CCDC114 CLN6 CUBN DPM1 EXOC4 FOXH1 GNA11 HPSE2 KCNA2 ABCA3 ALDH5A1 ATP6AP2 CCDC151 CLN8 CUL4B DPM2 EXOSC3 FOXI1 GNAI3 HRAS KCNB1 ABCA4 ALDH7A1 ATP6V0A2 CCDC22 CLP1 CUL7 DPM3 EXPH5 FOXL2 GNAO1 HSD17B10 KCND2 ABCB11 ALDOA ATP6V1B1 CCDC39 CLPB CXCR4 DPP6 EYA1 FOXP1 GNAS HSD17B4 KCNE1 ABCB4 ALDOB ATP7A CCDC40 CLPP CYB5R3 DPYD EZH2 FOXP2 GNE HSD3B2 KCNE2 ABCB6 ALG1 ATP8A2 CCDC65 CNNM2 CYC1 DPYS F10 FOXP3 GNMT HSD3B7 KCNH2 ABCB7 ALG11 ATP8B1 CCDC78 CNTN1 CYP11B1 DRC1 F11 FOXRED1 GNPAT HSPD1 KCNH5 ABCC2 ALG12 ATPAF2 CCDC8 CNTNAP1 CYP11B2 DSC2 F13A1 FRAS1 GNPTAB HSPG2 KCNJ10 ABCC8 ALG13 ATR CCDC88C CNTNAP2 CYP17A1 DSG1 F13B FREM1 GNPTG HUWE1 KCNJ11 ABCC9 ALG14 ATRX CCND2 COA5 CYP1B1 DSP F2 FREM2 GNS HYDIN KCNJ13 ABCD3 ALG2 AUH CCNO COG1 CYP24A1 DST F5 FRMD7 GORAB HYLS1 KCNJ2 ABCD4 ALG3 B3GALNT2 CCS COG4 CYP26C1 DSTYK F7 FTCD GP1BA IBA57 KCNJ5 ABHD5 ALG6 B3GAT3 CCT5 COG5 CYP27A1 DTNA F8 FTO GP1BB ICK KCNJ8 ACAD8 ALG8 B3GLCT CD151 COG6 CYP27B1 DUOX2 F9 FUCA1 GP6 ICOS KCNK3 ACAD9 ALG9 -

Recombinant Mouse Ngr (C-6His) Derived from Human Cells

Catalog # CM42 Recombinant Mouse NgR (C-6His) Derived from Human Cells Recombinant Mouse Nogo-66 Receptor/Reticulon 4 Receptor is produced by our Mammalian expression system and the target gene encoding Cys27-Ser447 is expressed with a 6His tag at the C-terminus. DESCRIPTION Accession Q99PI8 Known as Reticulon-4 Receptor; Nogo Receptor; NgR; Nogo-66 Receptor; RTN4R; NOGOR Mol Mass 46.6kDa AP Mol Mass 75-85 kDa, reducing conditions. QUALITY CONTROL Purity Greater than 95% as determined by reducing SDS-PAGE. Endotoxin Less than 0.1 ng/µg (1 EU/µg) as determined by LAL test. FORMULATION Lyophilized from a 0.2 μm filtered solution of PBS, pH 7.4. Always centrifuge tubes before opening. Do not mix by vortex or pipetting. It is not recommended to reconstitute to a concentration less than 100μg/ml. RECONSTITUTION Dissolve the lyophilized protein in distilled water. Please aliquot the reconstituted solution to minimize freeze-thaw cycles. The product is shipped at ambient temperature. SHIPPING Upon receipt, store it immediately at the temperature listed below. Lyophilized protein should be stored at < -20°C, though stable at room temperature for 3 weeks. STORAGE Reconstituted protein solution can be stored at 4-7°C for 2-7 days. Aliquots of reconstituted samples are stable at < -20°C for 3 months. Nogo Receptor (NgR) is a glycosylphosphoinositol (GPI)-anchored protein that belongs to the Nogo recptor family. Human NgR is predominantly expressed in neurons and their axons in the central nervous systems. As a receptor for myelin-derived proteins Nogo, myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and myelin BACKGROUND oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (OMG), NgR mediates axonal growth inhibition and may play a role in regulating axonal regeneration and plasticity in the adult central nervous system. -

Involvement of the Kinesin Family Members KIF4A and KIF5C In

Downloaded from http://jmg.bmj.com/ on March 10, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com Cognitive and behavioural genetics ORIGINAL ARTICLE Involvement of the kinesin family members KIF4A and KIF5C in intellectual disability and synaptic Editor’s choice Scan to access more free content function Marjolein H Willemsen,1,2 Wei Ba,1,3,4 Willemijn M Wissink-Lindhout,1 Arjan P M de Brouwer,1,2 Stefan A Haas,5 Melanie Bienek,6 Hao Hu,6 Lisenka E L M Vissers,1,2 Hans van Bokhoven,1,2,3,4 Vera Kalscheuer,6 Nael Nadif Kasri,1,2,3,4 Tjitske Kleefstra1,2 For numbered affiliations see ABSTRACT genes in the development and functioning of the end of article. Introduction Kinesin superfamily (KIF) genes encode nervous system. Mice with homozygous knockout Kif1a 1b 2a 3a 3b 4a 5a 5b Correspondence to motor proteins that have fundamental roles in brain mutations in , , , , , , and Dr Nael Nadif Kasri, functioning, development, survival and plasticity by show various neurological phenotypes including Department of Cognitive regulating the transport of cargo along microtubules structural brain anomalies, decreased brain size, Neuroscience, Radboud within axons, dendrites and synapses. Mouse knockout loss of neurons, reduced rate of neuronal apoptosis university medical center, studies support these important functions in the nervous and perinatal lethality due to neurological pro- Nijmegen, The Netherlands; 4–12 Nael.NadifKasri@radboudumc. system. The role of KIF genes in intellectual disability (ID) blems. The embryonic lethality of knockout nl; has so far received limited attention, although previous mice for Kif2a, Kif3a and 3b, and Kif5b suggest Dr Tjitske Kleefstra, studies have suggested that many ID genes impinge on that these Kif genes have an important function in Department of Human synaptic function. -

Site-Specific and Common Prostate Cancer Metastasis Genes

life Article Site-Specific and Common Prostate Cancer Metastasis Genes as Suggested by Meta-Analysis of Gene Expression Data Ivana Samaržija 1,2 1 Laboratory for Epigenomics, Division of Molecular Medicine, Ruder¯ Boškovi´cInstitute, Bijeniˇcka54, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory for Cell Biology and Signalling, Division of Molecular Biology, Ruder¯ Boškovi´cInstitute, Bijeniˇcka54, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Abstract: Anticancer therapies mainly target primary tumor growth and little attention is given to the events driving metastasis formation. Metastatic prostate cancer, in comparison to localized disease, has a much worse prognosis. In the work presented here, groups of genes that are common to prostate cancer metastatic cells from bones, lymph nodes, and liver and those that are site-specific were delineated. The purpose of the study was to dissect potential markers and targets of anticancer therapies considering the common characteristics and differences in transcriptional programs of metastatic cells from different secondary sites. To that end, a meta-analysis of gene expression data of prostate cancer datasets from the GEO database was conducted. Genes with differential expression in all metastatic sites analyzed belong to the class of filaments, focal adhesion, and androgen receptor signaling. Bone metastases undergo the largest transcriptional changes that are highly enriched for the term of the chemokine signaling pathway, while lymph node metastasis show perturbation in signaling cascades. Liver metastases change the expression of genes in a way that is reminiscent of processes that take place in the target organ. Survival analysis for the common hub genes revealed Citation: Samaržija, I. Site-Specific involvements in prostate cancer prognosis and suggested potential biomarkers. -

Sperm Differentiation

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Sperm Differentiation: The Role of Trafficking of Proteins Maria E. Teves 1,* , Eduardo R. S. Roldan 2,*, Diego Krapf 3 , Jerome F. Strauss III 1 , Virali Bhagat 4 and Paulene Sapao 5 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), 28006 Madrid, Spain 3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Chemistry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.E.T.); [email protected] (E.R.S.R.) Received: 4 March 2020; Accepted: 20 May 2020; Published: 24 May 2020 Abstract: Sperm differentiation encompasses a complex sequence of morphological changes that takes place in the seminiferous epithelium. In this process, haploid round spermatids undergo substantial structural and functional alterations, resulting in highly polarized sperm. Hallmark changes during the differentiation process include the formation of new organelles, chromatin condensation and nuclear shaping, elimination of residual cytoplasm, and assembly of the sperm flagella. To achieve these transformations, spermatids have unique mechanisms for protein trafficking that operate in a coordinated fashion. Microtubules and filaments of actin are the main tracks used to facilitate the transport mechanisms, assisted by motor and non-motor proteins, for delivery of vesicular and non-vesicular cargos to specific sites. -

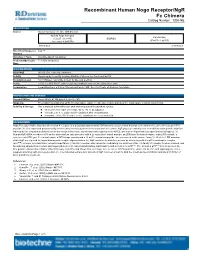

Recombinant Human Nogo Receptor/Ngr Fc Chimera

Recombinant Human Nogo Receptor/NgR Fc Chimera Catalog Number: 1208-NG DESCRIPTION Source Mouse myeloma cell line, NS0derived Human Nogo Receptor Human IgG (Cys27 Ser 447) IEGRMD 1 (Pro100 Lys330) Accession # Q9BZR6 Nterminus Cterminus Nterminal Sequence Cys27 Analysis Structure / Form Disulfidelinked homodimer Predicted Molecular 71.8 kDa (monomer) Mass SPECIFICATIONS SDSPAGE 95105 kDa, reducing conditions Activity Measured by its ability to bind rrMAG/Fc Chimera in a functional ELISA. Endotoxin Level <0.01 EU per 1 μg of the protein by the LAL method. Purity >95%, by SDSPAGE under reducing conditions and visualized by silver stain. Formulation Lyophilized from a 0.2 μm filtered solution in PBS. See Certificate of Analysis for details. PREPARATION AND STORAGE Reconstitution Reconstitute at 100 μg/mL in sterile PBS. Shipping The product is shipped at ambient temperature. Upon receipt, store it immediately at the temperature recommended below. Stability & Storage Use a manual defrost freezer and avoid repeated freezethaw cycles. l 12 months from date of receipt, 20 to 70 °C as supplied. l 1 month, 2 to 8 °C under sterile conditions after reconstitution. l 3 months, 20 to 70 °C under sterile conditions after reconstitution. BACKGROUND Nogo Receptor (NgR), also named reticulon 4 receptor, is a glycosylphosphoinositol (GPI)anchored protein that belongs to the family of leucinerich repeat (LRR) proteins (1). It is expressed predominantly in the central nervous systems in neurons and their axons. NgR plays an essential role in mediating axon growth inhibition induced by the structurally distinct myelinderived proteins Nogo, myelinassociated glycoprotein (MAG), and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (Omgp) (2, 3). -

Fast Transport of RNA Granules by Direct Interactions with KIF5A/KLC1 Motors Prevents Axon 2 Degeneration 3 4 Yusuke Fukuda1,2, Maria F

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.02.931204; this version posted February 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Fast Transport of RNA Granules by Direct Interactions with KIF5A/KLC1 Motors Prevents Axon 2 Degeneration 3 4 Yusuke Fukuda1,2, Maria F. Pazyra-Murphy1,2, Ozge E. Tasdemir-Yilmaz1,2, Yihang Li1,2, Lillian Rose1,2, Zoe 5 C. Yeoh2, Nicholas E. Vangos2, Ezekiel A. Geffken2, Hyuk-Soo Seo2,3, Guillaume Adelmant2,4, Gregory H. 6 Bird2,5,6, Loren D. Walensky2,5,6 Jarrod A. Marto2,4, Sirano Dhe-Paganon2,3, and Rosalind A. Segal1,2,7,* 7 8 1Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 9 2Department of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02115, USA 10 3Department of Biological Chemistry & Molecular Pharmacology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 11 02115, USA 12 4Blais Proteomics Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02115, USA 13 5Linde Program in Cancer Chemical Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02115, USA 14 6Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02115, USA 15 7Lead Contact 16 *Correspondence: [email protected] (R.A.S.) 17 18 19 20 Abstract 21 Complex neural circuitry requires stable connections formed by lengthy axons. To maintain these 22 functional circuits, fast transport delivers RNAs to distal axons where they undergo local translation.