Survey of Gross and Histopathologic Findings In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Conservation and Management of Indian Sarus Crane (Grus Antigone Antigone) in and Around Alwara Lake of District Kaushambi (U.P.), India

ISSN:150 2394-1391 Indian Journal of Biology Volume 5 Number 2, July - December 2018 Original Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21088/ijb.2394.1391.5218.7 Sustainable Conservation and Management of Indian Sarus crane (Grus antigone antigone) in and around Alwara Lake of District Kaushambi (U.P.), India Ashok Kumar Verma1, Shri Prakash2 Abstract The Indian Sarus crane, Grus antigone antigone is the only resident breeding crane of Indian subcontinent that has been declared as ‘State Bird’ by the Government of Uttar Pradesh. This is one of the most graceful, monogamous, non-migratory and tallest flying bird of the world that pair for lifelong and famous for marital fidelity. Population of this graceful bird now come in vulnerable situation due to the shrinking of wetlands at an alarming speed in the country. Present survey is aimed to study the population of sarus crane in the year 2017 in and around the Alwara Lake of district Kaushambi (Uttar Pradesh) India and their comparison to sarus crane population recorded from 2012 to 2016 in the same study area. This comparison reflects an increasing population trend of the said bird in the area studied. It has been observed that the prevailing ecological conditions of the lake, crane friendly behaviour of the local residents and awareness efforts of the authors have positive correlation in the sustainable conservation and increasing population trends of this vulnerable bird. Keywords: Alwara Lake; Conservation; Population Census; Sarus Crane; Increasing Trend. Introduction Author’s Affiliation: 1Head, Department of Zoology, Govt. P.G. College, Saidabad, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh 221508, India. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

Breeding Behaviour and Productivity of Black-Necked Crane (Grus Nigricolis) in Ladakh

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/809095; this version posted October 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Breeding behaviour and productivity of Black-necked crane (Grus nigricolis) in Ladakh, 2 Indian Trans-Himalaya 3 Pankaj Chandan1, Tanveer Ahmed2, Afifullah Khan2* 4 1WWF-India, 172-B, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi, India-110003 5 2Department of Wildlife Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India- 202002 6 *Corresponding author: 7 Email: [email protected] (AF) 8 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/809095; this version posted October 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 9 Abstract 10 A long-term study was conducted to understand some aspects of breeding biology of 11 Black-necked crane (Grus nigricollis) in Changthang, Ladakh. Data on aspects such as 12 the breeding season, courtship, mating, egg laying and incubation period, nest site 13 fidelity, egg morphometry, breeding productivity and recruitment rate were collected 14 between 2003 and 2012. Black-necked crane started arriving from last week of March 15 to first half of April and showed fidelity at ten nesting sites. Courtship and mating 16 peaked early morning (0700 hours), around noon (1100 hours) and in late evening 17 (0600 hours) while the nest building at evening (1600 hours). -

Sandhill Crane Antigone Canadensis

sandhill crane Antigone canadensis Kingdom: Animalia Division/Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Gruiformes Family: Gruidae ILLINOIS STATUS common, native FEATURES The sandhill crane averages about 40 to 48 inches in length (tail tip to bill tip in preserved specimen). This bird has a wingspan of six to seven feet. A red patch can be seen on the top of the bird’s head extending to the back edge of the bill. The feathers are gray in adults and brown in immature cranes. The crane has long legs and a long neck. The feathers over the rump stick out in a “bustle.” BEHAVIORS The sandhill crane is common in northern Illinois. It lives in prairies, fields (especially in corn fields), the edges of swampy areas, lakes and marshes. Spring migration begins in late February. The bird flies on good weather days and often does not land in Illinois. The sandhill crane has its nesting area in northern Illinois. The nest is a large pile of vegetation on the ground in a marshy area. Two, brown eggs with dark markings are deposited by the female. The male and female alternate incubation duties for the 31- to 32-day incubation period. Fall migration begins in mid- September. The sandhill crane winters in the southern United States from Florida to Texas. Cranes fly with the neck and legs extended. When migrating, they fly in flocks that are linear or in a "v" shape. The sandhill crane eats plant and animal materials. Its call is "garooo-a-a-a." HABITATS Aquatic Habitats lakes, ponds and reservoirs; marshes; peatlands; swamps; wet prairies and fens Woodland Habitats none Prairie and Edge Habitats black soil prairie; dolomite prairie; edge; gravel prairie; hill prairie; sand prairie; shrub prairie © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

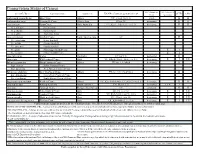

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Brolga Preying on Grebe Eggs

Australian Field Ornithology 2020, 37, 119–123 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo37119123 First observation of a Brolga Antigone rubicunda preying on eggs and of ‘water-kicking’ behaviour by Australasian Grebes Tachybaptus novaehollandiae as a nest-defence 1 Helen I. Dunne1 and Elinor C. Scambler2* 1‘Mt Benmore’, Marlborough QLD 4705, Australia 2P.O. Box 1383, Atherton QLD 4883, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. We report a novel observation of Australian waterbird behaviour: a Brolga Antigone rubicunda preying on eggs of the Australasian Grebe Tachybaptus novaeholliandiae, the first record of birds’ eggs in the diet of a crane in Australia. We also report ‘water-kicking’ by the Australasian Grebe, the first record of this anti-predator behaviour in the species. Neither Brolga diet nor display behaviours of the Australasian Grebe have been systematically investigated, and we suggest avenues for further studies of egg predation and parental defence behaviours in waterbird breeding wetlands. Introduction studies on Brolgas foraging, and for our understanding of distraction displays in the Australasian Grebe. Cranes are opportunistic omnivores (Mirande & Harris 2019), and the Brolga Antigone rubicunda is one of Study site several species that consume a significant proportion of animal foods (Gowland 1983; Marchant & Higgins 1993), Observations were made over 2 days in February 2019 especially in the breeding season (Sundar et al. 2019). We at ‘Mt Benmore’, a cattle-grazing property at 150 m asl, found eight published records of cranes (all in the genus 100 km north-west of Rockhampton (23°22′S, 150°30′E: Antigone) preying on birds’ eggs, but to date eggs have not Figure 1). -

Near-Ultraviolet Light Reduced Sandhill Crane Collisions with a Power Line by 98% James F

AmericanOrnithology.org Volume XX, 2019, pp. 1–10 DOI: 10.1093/condor/duz008 RESEARCH ARTICLE Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/condor/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/condor/duz008/5476728 by University of Nebraska Kearney user on 09 May 2019 Near-ultraviolet light reduced Sandhill Crane collisions with a power line by 98% James F. Dwyer,*, Arun K. Pandey, Laura A. McHale, and Richard E. Harness EDM International, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submission Date: 6 September, 2018; Editorial Acceptance Date: 25 February, 2019; Published May 6, 2019 ABSTRACT Midflight collisions with power lines impact 12 of the world’s 15 crane species, including 1 critically endangered spe- cies, 3 endangered species, and 5 vulnerable species. Power lines can be fitted with line markers to increase the visi- bility of wires to reduce collisions, but collisions can persist on marked power lines. For example, hundreds of Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis) die annually in collisions with marked power lines at the Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary (Rowe), a major migratory stopover location near Gibbon, Nebraska. Mitigation success has been limited because most collisions occur nocturnally when line markers are least visible, even though roughly half the line markers present include glow-in-the-dark stickers. To evaluate an alternative mitigation strategy at Rowe, we used a randomized design to test collision mitigation effects of a pole-mounted near-ultraviolet light (UV-A; 380–395 nm) Avian Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) to illuminate a 258-m power line span crossing the Central Platte River. We observed 48 Sandhill Crane collisions and 217 dangerous flights of Sandhill Crane flocks during 19 nights when the ACAS was off, but just 1 collision and 39 dangerous flights during 19 nights when the ACAS was on. -

The Cranes Compiled by Curt D

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Cranes Compiled by Curt D. Meine and George W. Archibald IUCN/SSC Crane Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union IUCN/Species Survival Commission Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Fund and The Cranes: Status Survey & Conservation Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission Conservation Communications Fund was established in 1992 to assist SSC in its efforts to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, deci- sion-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, occasional papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publi- cations are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and sup- port for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments and related support services. The President of CZS and Director of Brookfield Zoo, George B. Rabb, serves as the volunteer Chair of the SSC. The mis- sion of CZS is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mis- sion by informing and inspiring 2,000,000 annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. -

Phylogeny of Cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae) Based on Cytochrome-B Dna Sequences

The Auk 111(2):351-365, 1994 PHYLOGENY OF CRANES (GRUIFORMES: GRUIDAE) BASED ON CYTOCHROME-B DNA SEQUENCES CAREY KRAJEWSKIAND JAMESW. FETZNER,JR. • Departmentof Zoology,Southern Illinois University, Carbondale,Illinois 62901-6501, USA ABS?RACr.--DNAsequences spanning 1,042 nucleotide basesof the mitochondrial cyto- chrome-b gene are reported for all 15 speciesand selected subspeciesof cranes and an outgroup, the Limpkin (Aramusguarauna). Levels of sequencedivergence coincide approxi- mately with current taxonomicranks at the subspecies,species, and subfamilial level, but not at the generic level within Gruinae. In particular, the two putative speciesof Balearica (B. pavoninaand B. regulorum)are as distinct as most pairs of gruine species.Phylogenetic analysisof the sequencesproduced results that are strikingly congruentwith previousDNA- DNA hybridization and behavior studies. Among gruine cranes, five major lineages are identified. Two of thesecomprise single species(Grus leucogeranus, G. canadensis), while the others are speciesgroups: Anthropoides and Bugeranus;G. antigone,G. rubicunda,and G. vipio; and G. grus,G. monachus,G. nigricollis,G. americana,and G. japonensis.Within the latter group, G. monachusand G. nigricollisare sisterspecies, and G. japonensisappears to be the sistergroup to the other four species.The data provide no resolutionof branchingorder for major groups, but suggesta rapid evolutionary diversification of these lineages. Received19 March 1993, accepted19 August1993. THE 15 EXTANTSPECIES of cranescomprise the calls.These -

Downloaded on 19 March 2020

International Journal of Biological Research, 8 (1) (2020) 1-5 International Journal of Biological Research Website: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJBR Research paper Conservation status of amniotes found in and around Balapur Pond of District Prayagraj (Uttar Pradesh), India Ashok Kumar Verma* Department of Zoology, Government Post Graduate College, Saidabad Prayagraj-221508 (Uttar Pradesh), India *Corresponding author E-mail:[email protected] Abstract Perennial Balapur Pond was surveyed and studied to assess the conservation status of reptiles, birds and mammals naturally occurring in and around it. The survey was conducted from January 2018 to June 2019. During entire survey, a total of 7 species of reptiles, 11 spe- cies of birds and 8 species of mammals were identified. Among reptilian species reported, 1 species comes under NT (near threatened), 1 species LC (least concern) while 5 species have no special status (NSS). One avian species was CR (critically endangered), one NT (near threatened) and 9 bird species were LC (least concern). Out of 8 mammalian species recorded, one was EN (endangered), one VU (vul- nerable) and remaining 6 LC (least concern).Most of the avian and mammalian species are lacking conducive ambience and hunted for food. Keywords: Balapur Pond; Conservation status; Reptiles; Birds; Mammals; Red List. 1. Introduction Chordata is the highly evolved phylum among all animal phyla. These are characterized by the presence of dorsal tubular nerve cord, notochord and pharyngeal gill slits. The chordata is divided into lower chordata and higher chordata. The higher chordata is represented by a single subphylum Vertebrata in which notochord is replaced by vertebral column. -

NGT Preliminary Assessment of Brolga Genetics

Regional, Focussed, On-ground The development of microsatellite loci through next generation sequencing, and a preliminary assessment of population genetic structure for the iconic Australian crane, Brolga (Antigone rubicunda) Adam Miller This report may be cited as: Miller, A (2016). The development of microsatellite loci through next generation sequencing, and a preliminary assessment of population genetic structure for the iconic Australian crane, Brolga (Antigone rubicunda). Nature Glenelg Trust, Warrnambool, Victoria. For correspondence in relation to this report please contact: Mark Bachmann Manager Nature Glenelg Trust MOB: 0421 978 181 [email protected] Disclaimer Although reasonable care has been taken in preparing the information contained in this publication, Nature Glenelg Trust does not accept any responsibility or liability for any losses of whatever kind arising from the interpretation or use of the information set out in this publication. ii Acknowledgements Nature Glenelg Trust would like to express its sincere gratitude to the many members of the public who generously donated the funds required to initiate this project, along with a contribution of seed-funding from the Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority. We also wish to thank our close collaborators Inka Veltheim (Federation University, The University of Melbourne), Tim Nevard (Charles Darwin University & Wildlife Conservancy of Tropical Queensland), and Martin Haase (University of Greifswald) for the provision of Brolga samples for genetic analysis, and their intellectual contribution to our experimental design and editing of the final report (each will be formally recognised as a co-author on any publications stemming from this work). Many thanks also go out to Professor Christopher Austin and Han Ming Gan from Monash University’s Genomics Facility in Malaysia, for leading the genomic component of the project (more details of genome assembly and annotation will follow in a subsequent peer-reviewed publication). -

Unintentional and Intentional Poisoning Or Harassment of Cranes

DRAFT – DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION OF AUTHORS In: Harris J, Mirande C, editors. In preparation. Crane Conservation Strategy. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin. Contact: Claire Mirande, [email protected] UNINTENTIONAL AND INTENTIONAL POISONING OR HARASSMENT OF CRANES RELATED TO AGRICULTURE Jane Austin* (with input from Oleg Goroshko, Elena Ilyashenko, Eileen Kirsch, Anne Lacy, Fengshen Li, Claire Mirande, Kerryn Morrison, Gunter Nowald, and Triet Tran) *U.S. Geological Survey Global intensification of agriculture and concomitant increase in diversity and use of chemicals for control of plant, insect, and other pests threaten cranes that use agricultural landscapes. Crane mortalities have been linked to a range of chemicals, most commonly organophosphates and carbamates. Cranes also are expanding the types of agricultural habitats they use and foods they consume, which can expose them to novel chemicals or chemically treated situations. In developed countries, application of more toxic agrochemicals has declined as the most toxic chemicals have been banned, formulations have been improved for greater efficacy, and farmers’ understanding of applications have improved, but use continues to grow in developing countries (Ecobichon 2001). Poisoning risks to cranes from misuse or illegal use of agrochemicals are higher in developing countries where governments lack strong regulatory, registration, and educational systems for proper usage. D. Nankinov (2009) considers poisoning with DDT as the main reason for the extirpation Demoiselle Cranes on their breeding grounds in North-East Bulgaria. Residue levels of some of the more toxic agrochemicals remain high in some areas of South and Southeast Asia (Ali et al. 2014; Tran et al. 2014), exposing cranes to potentially damaging levels through their foods.