Barometer-Book-Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORF Issue Brief 102 Jayshree Sengupta

ORF ISSUE BRIEF AUGUST 2015 ISSUE BRIEF # 102 SAARC: The Way Ahead Jayshree Sengupta Introduction he South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)—comprising India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Nepal, Afghanistan and Pakistan—has been in Texistence as a regional grouping for almost 30 years (with Afghanistan joining in 2007). It has yet, however, to succeed in bringing about closer integration between the member countries. The idea behind SAARC—whose seed was sown by the late Bangladesh President Ziaur Rahman—was to promote regional cooperation and foster economic development and prosperity throughout the region. While the objectives enunciated in the SAARC charter signed in Dhaka in 1985 were to accelerate economic growth in the region and build mutual trust among member states, serious problems of cohesion remain and South Asia now stands as one of the least integrated regions in the world. After three decades of existence, intra-regional trade in South Asia is lower than that of other regional groupings. Intra-regional trade as a share of South Asia's total foreign trade was only 5 percent in 2014, against 25.8 percent for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries.1 The outcome of the 18th summit of SAARC, held in Kathmandu, Nepal, in November 2014, was not exceptional in any way. No concrete action was taken on the issues of terrorism, trade and foreign investment to validate the theme of the conference, 'Deeper Integration for Peace and Prosperity.' It was, as always, full of fanfare and rhetoric, and plenty of handshakes and promises were exchanged. -

REGIONAL CONSULTATION DEEPENING REGIONAL COOPERATION in SOUTH ASIA Expectations from the 18Th SAARC Summit Kathmandu, Nepal, November 23-24, 2014

REGIONAL CONSULTATION DEEPENING REGIONAL COOPERATION IN SOUTH ASIA Expectations from the 18th SAARC Summit Kathmandu, Nepal, November 23-24, 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The annual consumption of energy of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region is currently close to 700 million tonnes of oil equivalents (mtoe). It is projected to rise to 2000 mtoe by 2030. As the countries in South Asia move towards greater development, the energy needs are also certain to go up exponentially and energy security is therefore bound to be a priority for most of the countries. Many countries in the region do not have sufficient resources or technology to explore the available resources to meet their energy needs and thus, rely on imports which additionally need to be affordable in order to sustain the economic growth. Currently, energy trade and regional cooperation between the countries are minimal due to several reasons such as political, economic and security concerns. To give impetus to regional cooperation, there is a need for strong and robust political and social mandate. The existence of well-defined, coherent & harmonious energy policies, predictable legal and regulatory frameworks are essential principles for regional energy trade and investment. There is an urgent need to put in place related mechanism that would not only facilitate but also encourage energy trade in South Asia. Hence, collective efforts should be initiated to harmonise the prevailing legal and regulatory mechanisms that have been put in place among SAARC nations. Further, there is a need to establish infrastructure to facilitate and/or impede regional energy and synchronisation of all existing regulatory agencies in the manner that it will be convenient for them to coordinate electricity trade. -

Migration Year Book 2068.Indd

Nepal Migration Year Book 2010 NIDS NCCR North-South Book Nepal Migration Year Book 2010 Publishers Nepal Institute of Development Studies (NIDS) G.P.O. Box: 7647, Kathmandu, Nepal Email: [email protected] Web: www.nids.org.np National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South South Asia Coordination Offi ce Lalitpur, Nepal Email: [email protected] web: www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch Published Date 2011 Copyright NIDS ISBN: 978-9937-8112-6-2 Design, Layout & Print Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd. THE EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Anita Ghimire Dr. Ashok Rajbanshi Dr. Bishnu Raj Upreti Dr. Ganesh Gurung Dr. Jagannath Adhikari Dr. Susan Thieme RESEARCH TEAM Contributors Chapters 1. Dr. Ganesh Gurung Introduction 2. Dr. Janardan Raj Sharma Policy Framework 3. Dr. Ganesh Gurung Status and Trends of Labour Migration 4. Dr Jagannath Adhikari Migration and Remittance Economy 5. Ms. Puja Shakya Nepali Diaspora 6. Dr. Anita Ghimire Student Migration 7. Dr. Ashok Rajbanshi Migration of Nurses from Nepal 8. Ms. Joanna Green Somali Refugees in Nepal DISCLAIMER This publication can be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profi t purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided that acknowledgement of the source is made. The publishers appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the publishers. This publication holds entirely personal views and interpretations of the respective author(s). -

South Asia Satellite

South Asia Satellite Why in news? \n\n India launched ‘South Asia satellite’ on May 5 2017. This sends a positive signal to the neighbourhood. \n\n What are the facts about the satellite? \n\n \n The South Asia Satellite (GSAT-9) is a geosynchronous communications and meteorology satellite by the Indian Space Research Organisation. \n It is launched for the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region. \n This idea was mooted by India in 18th SAARC summit. \n Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Maldives and Sri Lanka are the users of the multi-dimensional facilities provided by the satellite. \n By launching the GSAT-9 ‘South Asia satellite’, India has reaffirmed the Indian Space Research Organisation’s scientific prowess, but the messaging is perhaps more geopolitical than geospatial. \n \n\n What are the benefits of the launch? \n\n \n The benefits the countries would receive in communication, telemedicine, meteorological forecasting and broadcasting. \n China is planning to launch a cloud for the countries in the south east region, but India wisely took the lead by lunching the SAARC satellite. \n It is prove once again that India is the only country in South Asia that has independently launched satellites on indigenously developed launch vehicles. \n More than scientific endeavour, this geopolitically strengthens India’s Strong neighbour’s policy. \n \n\n What is the hassle with Pakistan? \n\n \n In recent years Pakistan and Sri Lanka have launched satellites with assistance from China. \n Pakistan denied the trade permission between Afghanistan and India via the land route, this created distress mong the SAARC countries. -

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)

At a glance March 2015 The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) SAARC was founded in 1985, and is an economic and geopolitical organisation of eight countries located in southern Asia. However, the organisation has not advanced much in its three decades of existence, mainly because of the historic rivalry between India and Pakistan. This tension has blocked initiatives on several occasions, including at the November 2014 summit. Goals and structure The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was established, following a Bangladeshi initiative, in December 1985 in Dhaka. Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka were the founders, while Afghanistan joined in April 2007, to become the eighth member. The main goals of SAARC, as stated in its Charter, are: increasing the welfare of the peoples of South Asia, and the improvement of the quality of life through accelerated economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region. The Charter provides for annual, or more frequent, summits between the heads of state or government, but in reality this has often not been the case. The most recent SAARC Summit was held in 2014, three years after the previous one. The Council of Ministers formulates the policies of the Association and decides on new areas of cooperation. Foreign Ministers of the respective countries are members of this Council, which meets twice a year. A Standing Committee, composed of Foreign Secretaries, is in charge of the approval, monitoring and coordination of the SAARC's cooperation programmes. Meetings may also be convened at ministerial level on specific themes. -

Essay on Development Policy Learning from Nepal's First

Essay on Development Policy Learning from Nepal’s First Diaspora Bond Issuances Thomas Probst NADEL MAS-Cycle 2010-2012 March 2012 1 Abstract So far, only a few countries have launched diaspora bonds – Israel and India being the most prominent examples. In 2010 and 2011, Nepal’s central bank issued the country’s first diaspora bonds. Even though Nepal’s diaspora is large and provides a steady flow of remittances, the Government of Nepal could only raise a fraction of the amount initially expected. The weak market response was caused by several factors that need to be addressed in order to improve the results of similar bond issuances in the future. This paper identifies challenges and makes recommendations in a number of areas such as the narrow buyers universe, limitations in the distribution channels, regulatory challenges, technical issues, lack of a functioning secondary market, unattractive interest rates from an investor’s point of view, and a missing understanding among the market participants regarding the intended use of the raised funds. Key words: Diaspora, Bonds, Nepal, Remittance, Development Finance 2 Table of Content Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 2 Table of Content ................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4 2. Rationale -

Caste, Military, Migration: Nepali Gurkha Communities in Britain

Article Ethnicities 2020, Vol. 20(3) 608–627 Caste, military, migration: ! The Author(s) 2019 Nepali Gurkha communities Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Britain DOI: 10.1177/1468796819890138 journals.sagepub.com/home/etn Mitra Pariyar Kingston University, UK Oxford University, UK Abstract The 200-year history of Gurkha service notwithstanding, Gurkha soldiers were forced to retire in their own country. The policy changes of 2004 and 2009 ended the age-old practice and paved the way for tens of thousands of retired soldiers and their depend- ants to migrate to the UK, many settling in the garrison towns of southern England. One of the fundamental changes to the Nepali diaspora in Britain since the mass arrival of these military migrants has been the extraordinary rise of caste associations, so much so that caste – ethnicised caste –has become a key marker of overseas Gurkha community and identity. This article seeks to understand the extent to which the policies and practices of the Brigade of Gurkhas, including pro-caste recruitment and organisation, have contributed to the rapid reproduction of caste abroad. Informed by Vron Ware’s paradigm of military migration and multiculture, I demonstrate how caste has both strengthened the traditional social bonds and exacerbated inter-group intol- erance and discrimination, particularly against the lower castes or Dalits. Using the military lens, my ethnographic and historic analysis adds a new dimension to the largely hidden but controversial problem of caste in the UK and beyond. Keywords Gurkha Army, Gurkha migration to UK, caste and militarism, Britain, overseas caste, Nepali diaspora in England Corresponding author: Mitra Pariyar, Kingston University, Penrhyn Road, Kingston-Upon-Thames KT1 2EE, UK. -

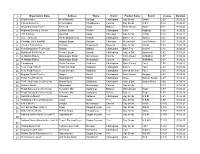

Organization Name Address Thana Distric Product Name Brand

1 Organization Name Address Thana Distric Product Name Brand License Duration 2 Shanti Bricks West Aburkhil Raozan Chattogram Clay Bricks Shanti C-03 30.06.22 3 Chiora Bricks Co Chiora Bazar Choddogram Cumilla Clay Bricks C B C C-12 30.06.21 4 Shahi Bakery & Confec. TA Road Sadar B-Baria White Bread Shahi C-17 30.06.21 5 Highway Sweets & Confec. Lalkhan Bazar Khulshi Chattogram Cake Highway C-20 30.06.22 6 A M S Bricks Moishadi Sadar Chandpur Clay Bricks A M S C-26 30.06.22 7 S.S. Tea House 99, Reazuddin road Kotwali Chattogram Black Tea Aurnov C-27 30.06.20 8 Chandan Oil & Atta Mill Hajiganj Bazar Hajiganj Chandpur Mustard Oil Jora Kobutar C-28 30.06.20 9 Amanat Bricks Manu Amnatpur Begumganj Noakhali Clay Bricks A B M C-40 30.06.20 10 New Bangladesh Tea House Bakalia Bakalia Chattogram Black Tea Nayem C-45 30.06.22 11 Bashkhali Salt Mills Ltd. Firingee Bazar Kotwali Chattogram Iodized Salt Bashkhali C-52 30.06.20 12 Al-Madina Bakery Muradnagar Bazar Muradnagar Cumilla White Bread Al-Madina C-57 30.06.22 13 Al-Madina Bakery Muradnagar Bazar Muradnagar Cumilla Biscuit Al-Madina C-58 30.06.22 14 Chadgaong South Burirchar Hathazari Chattogram White Bread Fulel C-60 30.06.22 15 Fulel Food Product South Burirchar Hathazari Chattogram Biscuit Fulel C-61 30.06.22 16 Fulel Food Product South Burichor Hathazari Chattogram Lachsa Shemai Fulel C-62 30.06.22 17 Bagdad Bread Factory Oxygen Baizid Chattogram White Bread Bagdad C-63 30.06.22 18 Tahar Food Products Nasirabad I/a Baizid Chattogram Ghee Danofa, Recipi C-67 30.06.21 19 Tarik Hasan Salt Crushing Ind. -

WP/IP Template

ADS-B SITF/15 – IP/16 Agenda Item 4 14/04/16 International Civil Aviation Organization FIFTEENH MEETING OF THE ADS-B STUDY AND IMPLEMENTATION TASK FORCE (ADS-B SITF/15) Bangkok, Thailand, 18 - 20 April 2016 Agenda Item 4: Review States’ activities and interregional issues on implementation of ADS-B and multilateration ADS-B AND MLAT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN IN BANGLADESH (Presented by Bangladesh) SUMMARY This paper presents revised plan of ADS-B and MLAT Implementation in Bangladesh. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Bangladesh wishes to inform the meeting that as Regulator and Air Navigation Service Provider, Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh (CAAB) provides CNS/ATM services. ADS-B is a surveillance technology supporting Radar like separation standards to enhance the flight safety and efficiency in Bangladesh. 1.2 Bangladesh has taken a Public Private Partnership (PPP) project that includes the installation of ADS-B ground stations throughout the country as back up to the proposed new radar systems and as a means of filling the gap in radar coverage over the Bay of Bengal area. 2. DISCUSSION 2.1 One of the primary safety objectives of ADS-B implementation is to provide surveillance coverage over the Bay of Bengal including the FIR boundary of Dhaka, Kolkata and Yangon ACC’s. 2.2 Bangladesh is willing to share ADS-B data and VHF RCAG communications with neighboring States to enhance the safety and surveillance capability in the Sub-region. 2.3 Bangladesh will install radar (PSR and MSSR) systems in two locations- one is at Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport, Dhaka under the ongoing PPP project and the other is at Shah Amanat International Airport, Chittagong under the on-going JICA funded project. -

A Case Study of Nepalese Organizations in Japan

JRCA Vol. 20, No. 1 (2019), pp.165-206 165 Roles of Migrant Organizations as Transnational Civil Societies in Their Residential Communities: A Case Study of Nepalese Organizations in Japan Masako Tanaka Faculty of Global Studies, Sophia University Abstract Japan is an immigration country whose economy cannot be sustained without foreign workers. However, the national government has done little for migrants, and municipalities and non-government organizations (NGOs) provide nominal services. The study examines the roles of migrant organizations through a case study of a self-help organization (SHO) in Gunma. Its primary role is organizing Nepalese migrants for mutual support. The secondary role is maintaining regular contact and collaboration with local governments and NGOs to provide an interface between migrants and other stakeholders to contribute to the integration of Nepalese migrants. The third role is developing transnational ties with Nepal, which is limited to emergency support. As the case of the SHO shows, migrant organizations can promote themselves as an interface between migrants and local stakeholders. Maintaining regular contact and collaboration with various stakeholders, they can be proactive civil society organizations that go beyond episodic participation in their residential communities. Key words: Migrant organization, Transnationalism, Nepal, Japan 166 Nepalese Migrant Organizations in Japan 167 Acknowledgements I am indebted to the leaders and members of the Nepalese migrant organizations for their patience in sharing their experiences with me. I would like to thank Taeko Uesugi, the convener of the panel “Migration and transnational dynamics of non-western civil societies” for her thoughtful comments and tireless engagement in editing this paper and the anonymous reviewers of the Japanese Review of Cultural Anthropology for their valuable comments. -

(IAIS) WELCOME Islam & Multiculturalism in Bangladesh

International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies (IAIS) WELCOME Islam & Multiculturalism in Bangladesh: A Reflection By Prof Dr Golam Dastagir September 12, 2012 1 British India 2 Bangladesh 3 Bangladesh 4 Prelude Religions and cultures are intertwined in each society. Culture means cultivation of the human mind and thus becomes synonymous with life and its activities, both inward and outward. Gandhi rightly says, “No culture can live if it attempts to be exclusive.” 5 Identity Crisis Muslims had lost their power to the British Imperialists in 1757 Muslims had refused to learn English, Stuck to Persian and Arabic languages to uphold their cultural identity in Islam (?). 6 Searching Identity in Islam Ahmede Hussain points out, “For around 200 years, date-trees, deserts and minarets epitomised Muslim culture in this part of Bengal. Some even took up surnames like Sheikh and Syed just to deny their Hindu past.” 7 Muslim’s backwardness But Hindus collaborated with the colonisers and occupied the lion’s share of power structure. Muslims, in general, lagged behind They became sub-ordinate to the Hindu boss, or ended up as domestic help called ‘Abdul’ in their kitchen. 8 Language Movement Bangalee Muslims voted for Jinnah's Two Nation Theory, got a jolt when the Pakistani ruling class refused to recognize their mother-tongue in 1952 as one of the state languages 21st February 1952 – language movement “International Mother Language Day” - UNESCO 9 Language Movement 10 Language Movement 11 Identifying root It was during the Pakistan era that the Bengali Muslims first tried to excavate its root They started to celebrate Pahela Baishakh and Choitro Shonkranti en mass, But the Pakistanis viewed them as a revival of Hindu culture in them. -

Custom House, Chittagong C&F Agent's Itc Statement

CUSTOM HOUSE, CHITTAGONG C&F AGENT'S ITC STATEMENT (IMPORT) PERIOD: JUL'16 - JUN'17 SLNO AIN NO NAME OF C&F AGENT Count of B/E NET WT.(KG) ASS.VAL (TK) CV (TK) ITC (TK) 1 301153938 A & E INTERNATIONAL 15 465,871.80 47,031,472.55 27,835.01 21,495.02 2 301154038 A & J TRADE INTERNATIONAL 156 5,452,686.56 913,963,726.06 499,895.95 333,238.94 3 301154200 A B S ASSOCIATES 907 9,610,656.81 2,453,610,952.86 108,314.82 1,189,674.03 4 301154193 A D T TRADERS 187 9,313,458.10 924,733,257.36 537,332.66 358,221.67 5 301154058 A F T LOGISTICS LIMITED 133 754,473.90 286,205,721.68 26,151.42 149,788.56 6 301133818 A G ENTERPRISE LTD 12 68,877.60 683,790,095.46 270,892.18 180,594.79 7 301113617 A K C & F LTD 198 23,528,309.20 1,135,391,507.11 568,059.88 432,584.05 8 301133812 A K M KNIT WEAR LIMITED 917 5,873,989.00 2,347,294,141.10 103,560.70 1,156,538.04 9 301154123 A R LOGISTIC 125 5,231,979.91 920,091,296.74 484,552.17 323,016.55 10 301153943 A S M CORPORATION 17 244,045.01 24,911,939.53 22,527.27 17,627.35 11 301154119 A T SHIPPING LINES 194 19,033,802.30 874,019,242.61 570,769.28 380,502.63 12 301831487 A.