Foraging Guild Status, Diversity and Population Structure of Waders Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Species in Delhi-“Birdwatching” Tourism

Conference Proceedings: 2 nd International Scientific Conference ITEMA 2018 BIRD SPECIES IN DELHI-“BIRDWATCHING” TOURISM Zeba Zarin Ansari 63 Ajay Kumar 64 Anton Vorina 65 https://doi.org/10.31410/itema.2018.161 Abstract : A great poet William Wordsworth once wrote in his poem “The world is too much with us” that we do not have time to relax in woods and to see birds chirping on trees. According to him we are becoming more materialistic and forgetting the real beauty of nature. Birds are counted one of beauties of nature and indeed they are smile giver to human being. When we get tired or bored of something we seek relax to a tranquil place to overcome the tiredness. Different birds come every morning to make our day fresh. But due to drainage system, over population, cutting down of trees and many other disturbances in the metro city like Delhi, lots of species of birds are disappearing rapidly. Thus a conservation and management system need to be required to stop migration and disappearance of birds. With the government initiative and with the help of concerned NGOs and other departments we need to settle to the construction of skyscrapers. As we know bird watching tourism is increasing rapidly in the market, to make this tourism as the fastest outdoor activity in Delhi, the place will have to focus on the conservation and protection of the wetlands and forests, management of groundwater table to make a healthy ecosystem, peaceful habitats and pollution-free environment for birds. Delhi will also have to concentrate on what birdwatchers require, including their safety, infrastructure, accessibility, quality of birdlife and proper guides. -

Waders of Dibru&Hyphen;Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary, Assam

Waders of Dibru-Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary, Assam Bibhab Kumar Talukdar Talukdar,B. K. 1996. Waders of Dibru-SaikhowaWildlife Sanctuary, Assam. Wader Study Group Bull. 80: 80-81. The status of waders in the Dibru-SaikhowaWildlife Sanctuary,Assam, is summarised. A total of 19 specieswere recordedfrom 14 field visits and other informationsupplied in the period 1990-1994. The Sanctuary has one of the richestwader faunas in Assam and its continued conservationis of key importance. B. K. Talukdar,Animal Ecology and VVildlifeBiology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Gauhati University,Guwahati - 781 014, Assam, India. In the past two decades, there has been increasing Bounded by the River Brahmaputra to the north and the concern about conservation of waders all over the world. River Dibru to the south, Dibru-Saikhowais purelya Data from the Asian Mid-winter Waterfowl Census in riparianhabitat comprising mostly wetlands and recentyears (1990-1994) reveal that the State of Assam grasslands,interspersed with medium to large patchesof (78 523 sq km) harboursaround 34 speciesof wader. A tree forests. The vegetationtypes of Dibru-Saikhowa preliminarysurvey of waders has been initiatedin the WLS can be classifiedinto - Tropical moist deciduous Dibru-SaikhowaWildlife Sanctuary (WLS) of Assam, forests,Tropical semi-evergreenforests, Bamboo and which is documented in this paper. cane brakes, Reedbedsand Alluvial grassland. The land use pattern of the sanctuaryis shown in Figure 2 but figure does not referto these habitatsspecifically. The BACKGROUND climate can be consideredas "Sub-tropicalMoist", the annual precipitationis 2 500-3 500 mm. The average temperaturevaries betweena maximum of 36ø C and a The Dibru-SaikhowaWLS (27ø 40'N, 95ø 24'E), covers 650 kin2 and is situated in the Tinsukia District of eastern minimumof 5ø C. -

Study on Avifaunal Diversity from Three Different Regions of North Bengal, India

Asian Journal of Conservation Biology, December 2012. Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 120 -129 AJCB: FP0015 ISSN 2278-7666 ©TCRP 2012 Study on avifaunal diversity from three different regions of North Bengal, India Utpal Singha Roy1*, Purbasha Banerjee2 and S. K. Mukhopadhyay3 1 Department of Zoology, Durgapur Government College, JN Avenue, Durgapur – 713214, West Bengal, India 2 Department of Conservation Biology, Durgapur Government College, JN Avenue, Durgapur – 713214, West Bengal, India 3 Department of Zoology, Hooghly Mohsin College, Chinsurah – 712101, West Bengal, India (Accepted November 15, 2012) ABSTRACT A rapid avifaunal diversity assessment was carried out at three different locations of north Bengal viz. Gorumara National Park (GNP), Buxa Tiger Reserve (BTR) (Jayanti/Jainty range) and Rasik Beel Wetland Complex (RBWC) during 2nd No- vember and 14th November 2008. A total of 117 bird species belonging to 42 families were recorded during the present short span study. The highest bird diversity was recorded in GNP with 87 bird species, followed by RBWC (75) and BTR (68). The transition zones between GNP and BTR, BTR and RBWC and GNP and RBWC were represented by 51, 41 and 57 common bird species, respectively. A total of 36 bird species were recorded in all three study sites. This diverse distribution of bird species was reflected in the study of diversity indices where the highest Shannon–Wiener diversity index score of 3.86 was recorded from GNP followed by RBWC (3.64) and BTR (2.84). The similar trend was also observed for Simpson’s Dominance Index, Pielou’s Evenness Index and Margalef’s Richness Index. -

First Record of a Regularly Occupied Nesting Ground of Yellow-Wattled

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2015; 3 (1): 129-134 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 First record of a regularly occupied nesting ground of JEZS 2015; 3 (1): 129-134 © 2015 JEZS Yellow-wattled Lapwing, Vanellus malabaricus Received: 08-01-2015 (Boddaert) in agricultural environs of Punjab with Accepted: 20-01-2015 notes on its biology Charn Kumar Department of Biology, A.S. College, Samrala Road, Khanna, Charn Kumar Distt. - Ludhiana (Punjab) – 141 401, India Abstract Amongst the three resident species of Lapwings reported from Punjab, the Yellow-wattled Lapwing, Vanellus malabaricus (Boddaert) is considered as a rare bird in Punjab. Except for some scattered sightings, to date, there has been no report of regular presence of Yellow-wattled Lapwing inhabiting a particular area in Punjab. During the present study spanning over a period of 12 months (January 2014 - December 2014), the hitherto unrecorded continuous occurrence of a group of individuals in a particular area (latitude: 30; 43; 52.60 N & longitude: 76; 09; 54.59 E) situated alongside the Delhi-Ludhiana National Highway past Khanna city have been noticed. In the months of April-May 2014, the two pairs of individuals laid a total of four clutches consisting of four eggs each. Preliminary observations have been made on its feeding, nesting and breeding biology. The presently recorded habitat is a private land and the lapwing individuals are facing twin threats of habitat deterioration and its eventual destruction. The study necessitates immediate initiatives for conservation and rehabilitation of this habitat, sustaining the continuous survival of this rare bird. -

India: Tigers, Taj, & Birds Galore

INDIA: TIGERS, TAJ, & BIRDS GALORE JANUARY 30–FEBRUARY 17, 2018 Tiger crossing the road with VENT group in background by M. Valkenburg LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: TIGERS, TAJ, & BIRDS GALORE January 30–February 17, 2018 By Machiel Valkenburg This tour, one of my favorites, starts in probably the busiest city in Asia, Delhi! In the afternoon we flew south towards the city of Raipur. In the morning we visited the Humayan’s Tomb and the Quitab Minar in Delhi; both of these UNESCO World Heritage Sites were outstanding, and we all enjoyed them immensely. Also, we picked up our first birds, a pair of Alexandrine Parakeets, a gorgeous White-throated Kingfisher, and lots of taxonomically interesting Black Kites, plus a few Yellow-footed Green Pigeons, with a Brown- headed Barbet showing wonderfully as well. Rufous Treepie by Machiel Valkenburg From Raipur we drove about four hours to our fantastic lodge, “the Baagh,” located close to the entrance of Kanha National Park. The park is just plain awesome when it comes to the density of available tigers and birds. It has a typical central Indian landscape of open plains and old Sal forests dotted with freshwater lakes. In the early mornings when the dew would hang over the plains and hinder our vision, we heard the typical sounds of Kanha, with an Indian Peafowl displaying closely, and in the far distance the song of Common Hawk-Cuckoo and Southern Coucal. -

Community Structure of Migratory Waterbirds at Two Important Wintering Sites in a Sub-Himalayan Forest Tract in West Bengal, India

THE RING 42 (2020) 10.2478/ring-2020-0002 COMMUNITY STRUCTURE OF MIGRATORY WATERBIRDS AT TWO IMPORTANT WINTERING SITES IN A SUB-HIMALAYAN FOREST TRACT IN WEST BENGAL, INDIA Asitava Chatterjee1, Shuvadip Adhikari2, Sudin Pal*2, Subhra Kumar Mukhopadhyay2 ABSTRACT Chatterjee A., Adhikari S., Pal S. Mukhopadhyay S. K. 2020. Community structure of migratory waterbirds in two important wintering sites at sub-Himalayan forest tract in West Bengal, India. Ring 42: 15-–37 The waterbird community structures of two sub-Himalayan wetlands (Nararthali and Rasomati) situated in forested areas were compared during the wintering period. These wetlands had similar geophysical features but were subject to different conservation efforts. Sixty species of waterbirds, including four globally threatened species, were recorded during the study. Nararthali was found to be more densely inhabited (116.05±22.69 ind./ha) by birds than Rasomati (76.55±26.47 ind./ha). Density increased by 44.6% at Nararthali and by 59% at Rasomati over the years of the study, from 2008 to 2015. Winter visitors increased considerably at Nararthali (66.2%), while a 71.1% decrease at Rasomati clearly indicated degradation of habitat quality at that site during the later years. Luxuriant growth of Eichhornia crassipes, siltation, poor maintenance and unregulated tourist activities were the key factors leading to the rapid degradation of Rasomati. Nararthali, on the other hand, a well-managed wetland habitat, showed an increasing trend in bird densities. Therefore, poor habitat management and rapid habitat alterations were observed to be the main reasons for depletion of bird density in the wetlands of eastern sub-Himalayan forest regions. -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt. -

River Yamuna

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.advancedjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May 2017; Page No. 76-80 River Yamuna: Virtual drain that supports avian life Sana Rehman Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental Studies, Rajdhani College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India Abstract Rivers is India has cultural, religious, social as well as economic importance. One such river is mythological river Yamuna which is a major tributary of the holy river Ganga. Pollution in this river has been well documented (Jain 2004, Paliwal et al 2007) especially through its stretch from Delhi. In this study we tried to document the dependence of birds on the river and Najafgarh Drain and sampled the variety of wetland birds found in this region. We identified at least 47 species of water birds in the wetlands of the region. Due to rapid urbanization we have been losing our aesthetic wealth, and the major cause is pollution, discharge of untreated water and encroachment along its stretch. Several policies and strategies should be made on grass root level to decrease the level of pollution in this holy river. Keywords: pollution, waterbirds, Yamuna, najafgargh drain, conservation. Introduction 3. Untreated wastewater from industries; According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) the 4. Agricultural runoffs (undetected and untreated pesticide water of river Yamuna falls under category “E” which makes residues leave a toxic mark all across the river) it suitable for using it either for industrial activities i.e. for 5. Dead body dumping, solid waste dumping and animal cooling or for recreations completely ruling out the washing. -

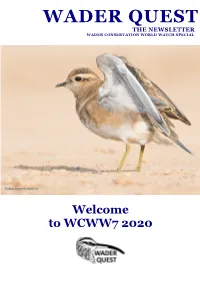

WCWW Newsletter Special

WADER QUEST THE NEWSLETTER WADER CONSERVATION WORLD WATCH SPECIAL Eurasian Dotterel © Shlomi Levi Welcome to WCWW7 2020 © Jean-François Cornuaille The new poster for WCWW was designed by Kirsty Yeomans aka Crow artist Contents: 20-22 - Missing species 2 - Statistics 23-31 - WCWW experiences 4-9 - Maps 32-45 - Summary 10 - Species list 46-47 - WCWW8 11-13 - Roll of Honour 48-56 - Gallery 14-15 - Participating organisation 57 - Wader Quest merchandising 16-19 - Observations 58 - Charity information © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 2 Participants Species Countries Continents Flyways WCWW 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Participants 70 182 241 327 309 252 489 Species 117 124 124 131 145 135 167 Countries 19 33 38 35 37 32 53 Continents 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 Flyways 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 3 EUROPE © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 4 AFRICA © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 5 ASIA © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 6 AUSTRALASIA & OCEANIA © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 7 NORTH AND CENTRAL AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 8 SOUTH AMERICA © Wader Quest 2020. All rights reserved 9 52. Black-headed Lapwing 110. Black-tailed Godwit SPECIES 53. African Wattled Lapwing 111. Hudsonian Godwit 54. River Lapwing 112. Bar-tailed Godwit LIST 55. Grey-headed Lapwing 113. Marbled Godwit 56. Red-wattled Lapwing 114. Eurasian Whimbrel 57. Yellow-wattled Lapwing 115. Hudsonian Whimbrel 58. Masked Lapwing 116. Eurasian Curlew 1. African Jacana 59. Black-shouldered Lapwing 117. -

Water Birds of Buxa Tiger Reserve, West Bengal

NOTE ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 19(4): 1451-1452 350 300 FAUNA OF PROTECTED AREAS - 6 250 WATER BIRDS OF BUXA TIGER RESERVE, 200 WEST BENGAL 150 100 No. of birds 50 S. Sivakumar and Vibhu Prakash 0 Nov DecJan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Bombay Natural History Society, Hornbill House, S.B. Singh Road, Months Mumbai, Maharashtra 400023, India. Figure 1. Water bird population in various months in Naratali (in Buxa Tiger Reserve) during 2000-2001 Buxa Tiger Reserve (26°30'-26°55'N & 89°20' & 89°55'E) is situated in Jalpaiguri District of West Bengal. The Reserve spreads over an area of 760 sq km with the core area being 385 (Grimmett et al., 1998; Kazmierczak, 2000). sq km. The northern boundary of the Reserve is along the international boundary of Bhutan. The eastern part of the Two small breeding colonies (about 30 pairs in each) of Small Reserve ends with the boundary of Assam. The western and Pratincole Glareola lactea was seen in Bala Riverbed of Jainty southern boundaries are bordered by tea gardens, agricultural Range. One nest of Malayan Night-Heron Gorsachius fields and human settlements. There are 37 villages inside and melanolophus was seen near Jindabala stream in Checko-23rd 33 tea gardens on the fringes of the Reserve. The forest of Mile Tower road. The Rydak Riverbed is the only place, where Buxa is broadly classified as tropical moist-deciduous forest Ibisbill Ibidorhyncha struthersii can be sighted in Buxa Tiger (Champion & Seth, 1968). The temperature ranges from a Reserve. We saw them in pairs and in small parties of four to six maximum of 32°C to minimum of 12°C and the average annual birds along the River near Bhutanghat guesthouse and rainfall is 4100mm. -

Birds and Tigers of Northern India

Dusky Eagle Owl on a nest at Keoladeo Ghana N.P. (all photos by Dave Farrow unless otherwise indicated) BIRDS AND TIGERS OF NORTHERN INDIA 21 NOVEMBER – 8 DECEMBER 2016 LEADER: DAVE FARROW This year’s ‘Birds and Tigers of Northern India’ tour was once again a very successful visual feast of avian delights. This tour is full of regional specialities and Indian subcontinent endemics, and among the many highlights were a total of 53 individual Owls seen of 9 species, including Dusky Eagle Owl on a nest, four Tawny Fish Owls and four Brown Fish Owls. We had great fortune with gamebirds, with three Cheer Pheasants plus stunning views of a pair of Koklass Pheasant, plus many Kalij Pheasants, Painted Spurfowl 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Birds and Tigers of Northern India www.birdquest-tours.com and Jungle Bush-Quail. We also saw Ibisbill, Red-naped Ibis, Black-necked Stork, Sarus Cranes, Indian, Himalayan and Red-headed Vulture, Pallas's and Lesser Fish Eagles, Brown Crake, Indian and Great Stone- curlew, Yellow-wattled and White-tailed Lapwing, Black-bellied and River Tern, Painted and Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse, and 15 species of Woodpecker including Great Slaty, Himalayan Pied, White-naped and Himalayan Flameback. We found plenty of Slaty-headed and Plum-headed Parakeet, Black-headed Jay, a Rufous-tailed Lark, Indian Bush Lark, the holy trinity of Nepal, Pygmy and Scaly-bellied Wren-Babblers, plus Brook’s Leaf Warbler, Black-faced and Booted Warbler, Black-chinned Babbler, six species of Laughingthrush including Rufous-chinned, Chestnut-bellied and White-tailed Nuthatch, Wallcreeper, Chestnut and Black-throated Thrushes, White-tailed Rubythroat, Golden Bush Robin, dapper Spotted Forktails, Blue-capped Redstart, Variable Wheatear, Fire-tailed Sunbird, Black-breasted Weaver, Altai Accentor, Brown Bullfinch, Blyth’s Rosefinch (a write-in), Crested, White-capped and Red-headed Bunting. -

Mammals Recorded in Ladakh

Map of the Indus Valley near Leh and the Rumbak section of Hemis National Park. Numbered localities: 1 Leh, 2 Shey Marshes, 3 Thiksey Monastery, 4 Zingchen, 5 Campsite, 6 Husing Valley, 7 Rumbak Village, 8 Urutse, 9 Ganda La / Kandala and 10 Tarbung Valley (map by Jon Lehmberg) Cover photo: Scenery in Tarbung Valley, 29th November 2010, ©Erling Krabbe Front page design by Jon Lehmberg. Trip report written by Ulrik Andersen, reviewed and improved by all participants. Bird and mammal lists by Morten Heegaard and Erling Krabbe. Photographs as indicated. Copenhagen, Denmark, January 2011. 2 Mammals recorded in Ladakh Mammal taxonomy as in "Birds and Mammals of Ladakh" by Otto Pfister (Oxford University Press, 2004), except as described in taxonomic notes. List compiled by Morten Heegaard. Snow Leopard Panthera uncia Several registrations of faeces, urine-markings and tracks during our stay in the area. A brief sighting of one walking high on a ridge against the sky at dusk by two observers (LH,UA) on 26th Nov. A very prolonged (over 4 hours), completely fantastic and unbelievable observation by the whole group of a "younger", but fully grown male (maybe 5 years old or so) in Tarbung Valley on 29th Nov. As noted in the diary, we were fortunate enough to observe a wide variety of behaviours and actions. A professional film crew would have been able to capture a lot of "BBC class" footage! How lucky can you get?! Taxonomic note: Recent research has demonstrated that the Snow Leopard is a Panthera. Earlier, it was placed in its own genus, and until recently the scientific name was Uncia uncia (the name used by Pfister).