Amyntas, Side, and the Pamphylian Plain P A R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Coins Collec Here Rises the Mighty Arch of Titus Tors Guild

Visit www.TomCederlind.com .. SYRACUSE. c. 404-400 Be. Silver Dekadrachm, unsigned dies by Kimon . .. .or call for a complimentary catalog .... TOM CEDERLIND NUMISMATICS & ANTIQUITIES PO Box 1963, Dept. C (5031228-2746 Portland, OR 97207 Fax (5031 228-8130 www.TomCederlind.com/[email protected] Vol. 21 , NO.7 The delator" Inside The Celato ~ ... July 2007 Consecutive Issue No. 241 lncolllora'ing Roman Coins' and e ulture FEATURES Publisher/Editor Kerry K. Wetterstrom [email protected] 6 Anepigraphic Bronze Coins of Constan tine and Family Associate Editors by Roben M. Harlick Robert L. Black Michael R. Mehalick 22 Faces of Empire-Part iX-imperium's Page 6 First Face (Alexander the Great and the For Back Issues From Successors) 1987 to May 1999 contact: by Cornelius Vermeule Wayne Sayles W<[email protected] 30 300,000 Archeological Items (and Coins) Seized in Raids in Spain Art: Parnell Nelson by Mark Gredler Maps & Graphic Art: Kenny Grady DEPARTMENTS P.O. Box 10607 2 Editor's Note ~ Goming Next Month Lancaste!", PA 17605 TeVFax: 717-656-8557 4 Letters to the Editor For FedEx & UPS deliveries: Kerry K. Wetterstrom 21 New Doubt Cast on Coins of Queen Boudica's 87 Apricot Ave Husband Leola, PA 17540·1788 by Chris Rudd www.celator.com The Celator (ISSN #1048·0986) 29 Then and Now, How Times Have Changed! Abo ut the cover: A is an independent journal pub lished on the first day of each The Ancient Coin Business from 1961-2007 photograph of an anepi month at 87 Apricot Ave, Leola. by Joel & Michael Malter graphic bronze coin of PA 17540-1788.1t is circulated in lernalionally through subscrip Constantine the Great tions and special distributions. -

Numismatic Public & Mail Bid Sale Monday, November 30, 1992* Hyatt Regency, Dearborn, Michigan

Classical Coins of Exceptional Quality Ancient, Medieval, Foreign & British Coins Numismatic Books Purchase, Sale, Auction & Valuation Regular Price Lists & Auction Catalogues (Complimentary Catalogue Upon Request) Annual Subscription $25/£15 ($351£20 overseas) Contact either our U.S. or u.K. office: (.L\ Seaby Coins ~ Eric J. McFadden, Senior Director 7 Davies Street London WIY ILL, United Kingdom (071) 495·1888, Fax (071) 499·5916 (.L\ Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ~ Victor England, Senior Director Post Office Box 245 Quarryville, PA 17566·0245 USA (717) 786·4013, Fax (717) 786·7954 INSIDE THE CELATOR ... Vol. 6, No. 11 FEATURES November 1992 6 VQTA PUBLICA: The origins of 'Tfz.e Ce{atoT voting in Rome and the use 01 coins for political purposes Publisher/Editor by Peter Bardy and Bill Whetstone Wayne G. Sayles Office Manager 10 Pixodarus-Alexander affair furnishes Janet Sayles intrigue for a blockbuster movie Page 6 Associate Editor by Mark Rakicic Steven A. Sayles VOTA PUBLICA by Peter 8erdy 14 Turbulent history of the RCCLiaison James L. Meyer and Bill Whetstone Crusades influenced a variety of early coinage types Production Asst. NickPopp by Margaret A. Graff Distribution Asst. 30 Roman coins found at Nineveh C hristine Olson provide evidence of trade Rochelle Olson between rival empires Art by Murray L. Eiland, 11/ Parnell Nelson Tho Co/atar 34 A poetic perspective: (ISSN 1110480986) is an independent joumal Apology for Numismatics published on the lirst by Brian A. Brown day of each month at Page 10 226 Palmer ParKway, Pixodarus-Alexander affair Lodi. Wt. It is circulated intemationally through by Mark Rakicic DEPARTMENTS sUbscriptions and special distributions. -

LHS Numismatics

Vol. 22, No. 10 Inside The Celatorv ... October 2008 Consecutive Issue No. 256 Incorporating Romall Coins and CU/lUre FEATURES PublisherlEdilor Kerry K. WeUerstrnm [email protected] 6 Dionysos Unmasked on Neapoliton Nomoi Associate Editors by Joseph Wihnyk Robert L. Black Michael R. Mehalick 20 Observations on the Madonna Denars of Page 6 Matthias Corvinus of Hungary-Part II For Back Issues From by Steven H. Kaplan 1.987 to May 1999 contact: Wayne Sayles 32 The Julius Caesar 'Elephant' Denarius: [email protected] What is the Symbolism? by James A. Hauck An: Parnell Nelson DEPARTMENTS Maps & Graphic An: Page 20 Kenny Grady 2 Guest Editorial by Ed Snible p.o. Box 10607 Coming Next Month Lancaster, PA 17605 TeUFax: 717-656-8557 4 Letters to the Editor For FedEx & UPS deliveries: Kerry K. Wetterstrom 36 People in the News 87 Apricot Ave tlroHtes in i2l11l1islIIlltirs Leola, PA 17540-1788 www.celator.com 37 Art and the Market Th6 C6/ator (lSSN 111048·0986) is an independent journal pub 40 Coming Events Page 32 lished on the !irst day of each month at 87 Apricot Ave, Leola. 42 e.-. &~ & ()~ PA 17540·1788. II is circulated in About the cover: A ternationally through subscrip by Mark Lehman tions and special distributions. marble circular relief Subscription rates, payable in 45 ANTIQ1JITI ES by David Liebert depicting Dionysos,ca. u.S. funds, are $36 per year (Pe 1"' century AD, photo riodical rate) within the United by States: $45 to Canada: $75 per 46 <!Co ins of t~c ~!'&ible David Hendin courtesy of the Metro year to all other addresses (ISAL). -

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm MISCELLANEOUS

2302 Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm Gold bullion bars (2), impressed Degussa, fi ne gold 999.9, 100g, 50g. Extremely fi ne - uncirculated. (2) $3,250 2303 Australian 1960 fl orin watch, by the Australian Coin Watch MISCELLANEOUS Company in original packet. Almost as new. $50 2293 2304 Storage cabinet, a large wooden box with two openings with Mexico, Maximillian, miniature, gold pesos and three U.S.A., 8 trays and a top opening shelf, all with metal latches and 8K coin miniature replicas. Uncirculated. (40) lockable base. Very fi ne. $180 $100 2305 2294 Jewllery, nine carat gold eternity ring, legacy badge and Deluxe Coin Albums, by Babors Manufacturing, N.S.W., button, sterling silver vesta case, hallmarked Chester 1902 with plastic page inserts and various pocket sizes. Good. by G.L & S. Fine. (4) (7) $60 $100 2295 2306 Coin albums (3) and loose pages, literature, Australia Post, The Royal Geographical Society Silver Map, in frame of pre stamped postcards, series III, Sydney 2000 Olympic Coin issue by Franklin Mint Pty Ltd 1976 gross weight 4.5 kg., Collection, packets. Unused. (8) silver approx 1.5 kg. FDC. $50 $350 2296 2307 Coin Accessories, a large cardboard box of various coin Mineral specimens, set of 12 issued with the compliments accessories, almost all new accessories, including new album of North Broken Hill Limited. leaves (for Hendo albums) (100's), containers for crown and $50 smaller coins, noted two Australia pre-decimal black plastic proof set holders (these are rare), new Hendo albums for Australian decimal, Fiji (3), British and general coins, new Whitman (see both sides) deluxe albums for Mexico, British pennies and halfpennies, GB type; Dansco deluxe Roosevelt dimes, etc. -

The Spread of Coins in the Hellenistic World

The Spread of Coins in the Hellenistic World Andrew Meadows Although coinage was first ‘invented’ in the archaic Greek period, and spread to a sig- nificant part of the Mediterranean world during the classical period, it remained a mar- ginal element within the economy. At very few cities or mints were coins produced regularly, and the issues of a vast majority of mints were sporadic, small and of coins ill- suited to daily transactions.1 Moreover there existed in the nature of early coinage inher- ent impediments to international use. Thus, while coinage can be said to be a financial innovation of the archaic and classical Greek world, it did not radically change eco- nomic behaviour. Significant changes in the nature and scale of coinage occurred only in the wake of Alexander’s world conquest, during the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic period runs, as usually defined, from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC to the Battle of Actium by which Roman superiority over the Greek world was finally established on 2nd September 31 BC. The period is defined by the world conquest of Alexander the Great, and the consequences of the division of his empire upon his death. The name ‘Hellenistic’ derives from the German term for the period, coined by J.G. Droysen in the 1830s in his Geschichte des Hellenismus (First edition, Hamburg 1836–1843). For Droysen, who had previously written a seminal study of Alexander the Great, the period of Hellenismus, was characterised by the Hellenisation of the world that Alexander had conquered. This world had largely been encompassed by the Achaemenid Persian Empire, but had comprised many different cultures in Asia Minor, the Near East, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran and beyond.2 1 On scale, see further below, section “Spread and Scale”. -

RNS-BNS Library Book Catalogue 20200428

Section Sub-Category Label AU - Author 1 Author 2 Author 3 Author 4 ISBN TI - Title PU - Publisher SE - Series/Source MV - Multi Volume Place PY - Pub_Date PD - Physical Description LA - Language LA - Language 2 LA - Language 3 LA - Language 4 Keywords Edition Society OCLC A1. Selbstwahrnehmung und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Fundmünzenbearbeitung : Bilanz Etudes de numismatique et d'histoire monétaire = A A1 ACK. Ackermann, Rahel C. Derschka, Harald R. Mages, Carol 9782940351046 und Perspektiven am Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts = Regards croises sur l'etude des Lausanne : Éditions de Zèbre Untersuchungen zu Numismatik und I. Materialien Lausanne 2005 229 pages : ill., maps ; 24 cm. German French English R 728068443 0995 trouvailles monetaires : bilan et perspectives au debut du XXIe siecle Geldgeschichte, 6. A1. A A1 ACQ. Acquaro, Enrico Le monete puniche del Museo Nazionale di Cagliari : Catalogo Roma : Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche Collezione di studi fenici, 4. Roma 1974 96, 26 pages, 100 pages of plates : illustrations ; 29 cm. Italian Greek R 217263391 0616 A1. A A1 AKE. Akerman, John Yonge Numismatic Illustrations of the Narrative Portions of the New Testament Chicago : Argonaut Argonaut library of antiquities Chicago 1966 vii, 62 pages : illustrations ; 22 cm. English Jewish R 617034 0720 A1. A A1 ALL. Allotte de la Fuÿe, François Maurice Monnaies de l'Elymaide Chartres : Imprimerie Durand Chartres 1905 67 p., [5] leaves of prints: illustrations ; 33 cm. French Greek R 759753408 0142 A1. Athènes : École française d'Athènes : Paris : Bulletin de correspondance hellénique., A A1 AMA. Amandry, Michel 9782869580138 Le Monnayage des Duovirs Corinthiens Paris 1988 269 pages, xlviii pages of plates : illustrations ; 26 cm. -

Tite Valls of Nicaea Jalius Caesar 'Elepitant' Coinage

$CuLAroH >a HI ZH 6s El I{ ZH t)-.i -&. TITE VALLS OF NICAEA . FURTIIER TITOUGITTS ON TI:IE JALIUS CAESAR 'ELEPITANT' COINAGE Visit www.TomCederlind.com ... SYRACUSE. c. 404-400 Be. Silver Dekadrachm, unsigned dies by Kinwn . .. .or call for a complimentary catalog .... TOM CEDERLIND NUMISMATICS & ANTIQUITIES PO Box 1963, Dept. C 15031228·2746 Portland, OR 97207 Fax 15031 228·8130 www.TomCederiind.com/[email protected] Vol. 24, No.4 Inside The Celator'" ... April 2010 ncorporating Consecutive Issue No. 274 Roman Cainl'and euifllre FEATURES PublisherlEditor Kerry K. Wetterstrom [email protected] 6 The Walls of Nicaea by Walter C. Holt, M.A. Associate Editors Further Thoughts on the Julius Caesar Robert L. Black 20 Michael R. Mebalick 'Elephant' Coinage Page 6 by Mike Gasvoda For Back lNles From J987 to May 1999 contact: DEPARTMENTS Wayne Sayles [email protected] 2 Editor's Note Coming Next Month Art: Parnell Nelson 32 Art and the Market f)rofilcS' in j}umiS'matirS' Maps & Graphic Art: Art and the Market Page 20 Kenny Grady 33 36 Coming Events P.O. Box 10607 L.anca8t1tr, PA 17605 38 Special ized Shows: The San Francisco Historical TeUFax : 717~557 Bourse by Victor England For FedEx & UPS deliveries: Kerry K. Wetterstrom 41 ANT IQlJ ITl E5 by David Liebert 87 Apricot Ave Leola, PA 17540· 1788 42 Q[ oins of to e ~ ib[ e by David Hendin www.cetator.com 44 The Internet Connection The Gelator (ISSN #t048·0986) is an independent journal pub· by Kevin Barry & Zachary "Beasf' Beasley lished on the first day of each month at 87 Apricot Ave. -

Compte Rendu 51 2004

COMISIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE NUMISMÁTICA INTERNATIONAL NUMISMATIC COMMISSION COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE DE NUMISMATIQUE INTERNATIONALE NUMISMATISCHE KOMMISSION COMMISSIONE INTERNAZIONALE DI NUMISMATICA Compte rendu 51 2004 Publié par le Secrétariat de la Commission INTERNATIONAL NUMISMATIC COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE DE NUMISMATIQUE TABLE OF CONTENTS/SOMMAIRE Composition du Bureau . .7 Statuts . .9 Constitution . .11 Les grands numismates Michael Grant (1914-2004) (Michel Amandry) . .13 Histoire des collections numismatiques et des institutions vouées à la numismatique Princeton University Library (Brooks E. Levy & Alan M. Stahl) . .20 Il Medagliere del Museo Nazionale Romano (Fiorenzo Catalli) . .25 Nécrologie Rudi Thomsen (1918-2004) (Erik Christiansen) . .30 Jirˇí Sejbal (1929-2004) (Stanisl/aw Suchodolski) . .32 Ya‘akov Meshorer (1935-2004) (Haim Gitler) . .36 Crónica del XIII Congreso Internacional de Numismática (15-19 septiembre 2003) . .39 Meeting of the Council (Athens 27-28 March 2004) . .57 Comptes de la Commission . .58 Membres de la Commission Institutions . .83 Membres honoraires . .101 Annual Scholarship of the INC . .103 5 COMISIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE NUMISMÁTICA INTERNATIONAL NUMISMATIC COMMISSION COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE DE NUMISMATIQUE INTERNATIONALE NUMISMATISCHE KOMMISSION COMMISSIONE INTERNAZIONALE DI NUMISMATICA BUREAU elected on September 14th, 2003 in Madrid/élu le 14 septembre 2003 à Madrid Président: M. Michel AMANDRY, Cabinet des Médailles de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, 58 rue de Richelieu, F - 75084 Paris cedex 02, France. Tel. + 33 1 53 79 83 63, fax + 33 1 53 79 89 47 E-mail: [email protected] Vice-présidents: Dr. Carmen ALFARO, Departamento de Numismática y Medallis- tica, Museo Arqueológico Nacional, c/Serrano 13, E - 28001 Madrid, Spain. Tel. + 34 1 5777912, fax + 34 1 4316840 E-mail : [email protected] Prof. -

Numismatic Literature

NUMISMATIC BOOKS - GREEK & GREEK IMPERIAL Collections [Alpha Bank] Tsangari, D.I., ed. Coins of Macedonia in the Alpha Bank Collection. Alpha Bank. Athens. 2009. [Alpha Bank] -----. Alexander the Great from Macedonia to the Edge of the World. Alpha Bank. Athens. 2010. [Alpha Bank] -----. Hellenic Coinage: The Alpha Bank Collection. Alpha Bank. Athens. 2007. [Alpha Bank] -----. The Europe of Greece: Colonies and Coins from the Alpha Bank Collection. Alpha Bank. Athens. 2014. [Berlin] Sallet, A. von., and H. Dressel. Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Beschreibung der antiken Münzen. 3 vols. W. Spemann. Berlin. 1888-1923. [Benson] Benson, F.S. Ancient Greek Coins. NP. c. 1904. [Collected contemporary reprint of articles from American Journal of Numismatics. Parts 1-14 (1901-4) only, missing 15-16] [Bibliotheque National] Dieudonne, A. Choix de monnaies et médailles du cabinet de France. Monnaies grecques d’Italie et de Sicile. Rollin et Feuardent. Paris. 1913. [Boston I] Brett, A.B. Catalogue of Greek Coins. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Boston. 1955. [Boston II] Comstock, M., and C. Vermeule. Greek Coins. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Boston. 1964. [British Museum] Head, B.V. Catalogue of the Greek Coins of Ionia. A Catalogue of Greek Coins in the British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum. London. 1892. [Courtauld] Pollard, G. A Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the Collection Sir Stephen Courtauld at the University College of Rhodesia. University College of Rhodesia. Salisbury. 1970. [Credit Bank] Walker, A. Ancient Greek Coins, The Credit Bank Collection. Hellenic Numismatic Society. Athens. 1978. [Davis] Troxell, H.A. The Norman Davis Collection. Greek Coins in North American Collections. -

ARETIIUSA,S ENIGMATIC IIEADBAND the NEW YORK SALE'" Partner Finns Will Be Accepting Consignments at the ANA World's Fair of Money, August 16-20, 2011 at Table No

HCpLAToR r3 ,t ttl H2:9 >9 5s,) -r f,] IQ z -ll o . A NAMISMATIC BIOGR}IPHY OF LUCIAS CORNELIUS SALLA . ARETIIUSA,S ENIGMATIC IIEADBAND THE NEW YORK SALE'" Partner Finns will be accepting consignments at the ANA World's Fair of Money, August 16-20, 2011 at Table No. 209, and at the Whitman Philadelphia Coin Expo on Sept. 15-17, 2011 at Table No. 233. Please visit us if you want your coins to be part of our record-breaking sales held in conjunction with the New York International Numismatic Convention in January 2012. For further information, please call Lucien Birkler at 1-203-815-2765. Baldwin's Dmitry Markov M&M Auction Ltd. Coins & i\ledaJs ;\Iumismatics Ltd. I I Adelphi Terrace P. O. Box 950 P. O. Box 65908 London, WC2N 618, UK New York, NY 10272, USA Washington, DC 20035. USA Tel.: 44/20 7930 9808 TeL: 1/9084702828 Tel.: [/2028333770 Fax: 44120 7930 9450 Fax: 1/9084700088 Fax: 112024295275 e-mail : [email protected] e-mai l: [email protected] Cell: 1/2 038152765 Vol. 25, No.9 The 13elatot'" Inside The Celator® ... September 2011 Consecutive Issue No. 291 Incorporating Roman Coins (lnd Culture FEATURES Publisher/Editor Kerry K. WeUerstrom [email protected] 6 A Numismatic Biography of Lucius Cornelius Sulla Associate Editors by Sam Spiegel Robert L. Black Michael R. Mehalick 30 Arethusa's Enigmatic Headband Page 6 by Lawrence Sekulich For Back Issues From 1987 to May 1999 contact: DEPARTMENTS Wayne Sayles [email protected] 2 Editor's Note Art: Parnell Nelson Coming Next Month 4 Book News - Ancient British Coins Maps & Graphic Art: tlrofilts in j1111l1istniltiC5 Kenny Grady 34 36 Coming Events p,e. -

Ancient Coins ," Which Appeared in the a Beginner's Guide Coins." He Also Received the Ira and August Issuc

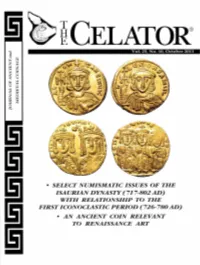

T H E _ELATOR® Vol. 25, No. 10, October 2011 • SELECT NUMISMATIC ISSUES OF THE ISAURIAN DYNASTY (717-802 AD) WITH RELATIONSHIP TO THE FIRST ICONOCLASTIC PERIOD (726-780 AD) • AN ANCIENT COIN RELEVANT TO RENAISSANCE ART Collect-ton Pantikapaion Gold Stater Kyrene Tetradrachm A Classical Masterpiece Syracuse Dekadrachm Head of Zeus Ammon An Icon of Ancient Greek Coinage A Magisterial Specimen The Majestic Art ot Coins Over 600 Spectacular and Historically Important Greek Coins To be auctioned at the Waldorf Astoria, NEW YORK, 4 January 2012 A collection of sublime quality, extreme rarity, supreme artistic beauty and of exceptional historical importance. It has been over 20 years since such a comprehensive collection of high quality ancient Greek coins has been offered for sale in one auction. Contact Paul Hill ([email protected]) or Seth Freeman ([email protected]) for a free brochure Vol. 25, No. 10 The Celator" Inside The Celafof'ID ... October 2011 Consecutive Issue No. 292 Incorporating RomGII Coins mId Culture FEATURES PublisherfEdilor Kerry K. Wetterslrom [email protected] 6 Select Numismatic Issues of the Isaurian Dynasty (717·802 AD) with Relationship to A"-SOCiale Editors the First Iconoclastic Period (726·780 AD) Robert L. Black by Spero Kinnas Mkhael R. Mehalick Page 6 18 An Ancient Coin Relevant to For Back lssues From Renaissance Art 1987 to May 1999 contact: by Peter E. Lewis Wayne Sayles wgs @wgs.cc DEPARTMENTS Art: Parnell Nelson 2 Editor's Note Maps & Graphic Art: Coming Next Month Page 18 Kenny Grady 4 Letters to the Editor P.O. -

Sale 158 IMPORTANT NUMISMATIC LITERATURE

Sale 158 IMPORTANT NUMISMATIC LITERATURE Featuring Material from the TAB Library, the Eldert Bontekoe Library, & Other Properties Mail Bid & Live Online Auction Saturday, November 21 at 12:00 Noon Eastern Time Place bids and view lots online at BID.NUMISLIT.COM Absentee bids placed by post, email, fax or phone due by midnight Friday, November 20. Absentee bids may be placed online at any time before the sale. 141 W. Johnstown Road • Gahanna, Ohio 43230 (614) 414-0855 • Fax (614) 414-0860 • numislit.com • [email protected] Terms of Sale 1. This is an online and mail-bid sale. Absentee bids will be accepted by mail, fax, email and phone until the day before the live online sale. On the day of the live online sale, only bids placed via the live online platform will be accepted: no phone, fax, email or mail bids can be entered on the day of the sale. 2. All lots will be sold to the highest bidder at the time of the sale. All bids (whether placed online or by mail, fax, email or phone) will be treated as limits and lots will be purchased below these limits where competition permits. 3. Absentee bidders should be mindful that bids submitted in irregular increments may be rounded to a lower bid to comply with the online platform’s established bidding increments. 4. Unless exempt by law, the buyer will be required to pay 7.5% sales tax on the total purchase price of all lots delivered in Ohio. Purchasers may also be liable for compensating use taxes in other states, which are solely the responsibility of the purchaser.