Conservation Research on Spotted Eagle Rays in Florida and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharkcam Fishes

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2020. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 201 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 5.0. 24 February 2020. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index TABLE OF CONTENTS SILVERY FISHES (23) ........................... 47 African Pompano ......................................... 48 FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION .............. 6 Crevalle Jack ................................................. 49 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES ...................... 10 Permit .......................................................... 50 Sharks and Rays ........................................ 10 Almaco Jack ................................................. 51 Illustrations of SharkCam -

Aetobatus Ocellatus, Ocellated Eagle Ray

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T42566169A42566212 Aetobatus ocellatus, Ocellated Eagle Ray Assessment by: Kyne, P.M., Dudgeon, C.L., Ishihara, H., Dudley, S.F.J. & White, W.T. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Kyne, P.M., Dudgeon, C.L., Ishihara, H., Dudley, S.F.J. & White, W.T. 2016. Aetobatus ocellatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T42566169A42566212. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T42566169A42566212.en Copyright: © 2016 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Chondrichthyes Rajiformes Myliobatidae Taxon Name: Aetobatus ocellatus (Kuhl, 1823) Synonym(s): • Aetobatus guttatus (Shaw, 1804) • Myliobatus ocellatus Kuhl, 1823 Common Name(s): • English: Ocellated Eagle Ray Taxonomic Source(s): White, W.T., Last, P.R., Naylor, G.J.P., Jensen, K. -

The Ecology and Biology of Stingrays (Dasyatidae)� at Ningaloo Reef, Western � Australia

The Ecology and Biology of Stingrays (Dasyatidae) at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2012 Submitted by Owen R. O’Shea BSc (Hons I) School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology Murdoch University, Western Australia Sponsored and funded by the Australian Institute of Marine Science Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content, work that has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ........................................ ……………….. Owen R. O’Shea Date I Publications Arising from this Research O’Shea, O.R. (2010) New locality record for the parasitic leech Pterobdella amara, and two new host stingrays at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Marine Biodiversity Records 3 e113 O’Shea, O.R., Thums, M., van Keulen, M. and Meekan, M. (2012) Bioturbation by stingray at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research 63:(3), 189-197 O’Shea, O.R, Thums, M., van Keulen, M., Kempster, R. and Meekan, MG. (Accepted). Dietary niche overlap of five sympatric stingrays (Dasyatidae) at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Journal of Fish Biology O’Shea, O.R., Meekan, M. and van Keulen, M. (Accepted). Lethal sampling of stingrays (Dasyatidae) for research. Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching. Annual Conference on Thinking outside the Cage: A Different Point of View. Perth, Western Australia, th th 24 – 26 July, 2012 O’Shea, O.R., Braccini, M., McAuley, R., Speed, C. and Meekan, M. -

First Ecological, Biological and Behavioral Insights of the Ocellated Eagle Ray Aetobatus Ocellatus in French Polynesia Cecile Berthe

First ecological, biological and behavioral insights of the ocellated eagle ray Aetobatus ocellatus in French Polynesia Cecile Berthe To cite this version: Cecile Berthe. First ecological, biological and behavioral insights of the ocellated eagle ray Aetobatus ocellatus in French Polynesia. Biodiversity and Ecology. 2017. hal-01690359 HAL Id: hal-01690359 https://hal-ephe.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01690359 Submitted on 23 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MINISTÈRE DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE ÉCOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ÉTUDES Sciences de la Vie et de la Terre MÉMOIRE Présenté par Cécile Berthe pour l’obtention du Diplôme de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études Première approche écologique, biologique et comportementale de la raie aigle à ocelles Aetobatus ocellatus en Polynésie française soutenu le 10 octobre 2017 devant le jury suivant : Clua Eric – Président Iglésias Samuel – Tuteur scientifique Lecchini David – Tuteur pédagogique Bernardi Giacomo – Rapporteur Chin Andrew – Examinateur Mémoire préparé sous -

Observations of Spotted Eagle Rays (Aetobatus Narinari) in the Mexican Caribbean Using Photo-ID

Environ Biol Fish https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-017-0694-y Observations of spotted eagle rays (Aetobatus narinari) in the Mexican Caribbean using photo-ID F. Cerutti-Pereyra & K. Bassos-Hull & X. Arvizu-Torres & K. A. Wilkinson & I. García-Carrillo & J. C. Perez-Jimenez & R. E. Hueter Received: 25 March 2017 /Accepted: 30 October 2017 # Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature 2017 Abstract The spotted eagle ray is an iconic species for catalog of spotted eagle rays in the Mexican Caribbean the recreational diving and snorkeling industry in the using 1096 photographs submitted by researchers and Mexican Caribbean although it is heavily fished in divers between 2003 and 2016. In total, 282 individual nearby waters of the southern Gulf of Mexico and in spotted eagle rays were identified through photographs Cuba. This species is listed on the IUCN Red List of at nine sites across the Mexican Caribbean. Of these Threatened Species as ‘Near Threatened’ with a de- individuals, 14.9% were resighted at least once at the creasing population trend. Few studies have reported same site. The longest period between re-sighting events on the populations and migrations of spotted eagle rays was 342 days. This is the first study evaluating free- in the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean swimming spotted eagle rays in the Mexican Caribbean Sea, and no regulations currently exist for the fishery or and highlights the value of using photo-ID for monitor- tourism industries in Mexico. Photographic identifica- ing populations of this ray. Because a targeted subsis- tion techniques were used to produce the first photo-ID tence fishery for spotted eagle rays exists in nearby waters, management efforts to monitor and prevent : : overexploitation at key diving locations should be a F. -

Bio-Ecological Features Update on Eleven Rare Cartilaginous Fish in the Central-Western Mediterranean Sea As a Contribution for Their Conservation

life Article Bio-Ecological Features Update on Eleven Rare Cartilaginous Fish in the Central-Western Mediterranean Sea as a Contribution for Their Conservation Antonello Mulas 1,2,*,†, Andrea Bellodi 1,2,† , Pierluigi Carbonara 3 , Alessandro Cau 1,2 , Martina Francesca Marongiu 1,2 , Paola Pesci 1,2, Cristina Porcu 1,2 and Maria Cristina Follesa 1,2 1 Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Cagliari, 09126 Cagliari, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (M.F.M.); [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (M.C.F.) 2 CoNISMa Consorzio Nazionale Interuniversitario per le Scienze del Mare, 00196 Roma, Italy 3 COISPA Tecnologia & Ricerca, 70126 Bari, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Authors contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors. Abstract: Cartilaginous fish are commonly recognized as key species in marine ecosystems for their fundamental ecological role as top predators. Nevertheless, effective management plans for cartilagi- nous fish are still missing, due to the lack of knowledge on their abundance, distribution or even life-history. In this regard, this paper aims at providing new information on the life-history traits, such as age, maturity, reproductive period, in addition to diet characteristics of eleven rare cartilagi- Citation: Mulas, A.; Bellodi, A.; nous fish inhabiting the Central-Western Mediterranean Sea belonging to the orders Chimaeriformes Carbonara, P.; Cau, A.; (Chimaera monstrosa), Hexanchiformes (Heptranchias perlo and Hexanchus griseus), Myliobatiformes Marongiu, M.F.; Pesci, P.; Porcu, C.; Follesa, M.C. Bio-Ecological Features (Aetomylaeus bovinus and Myliobatis aquila), Rajiformes (Dipturus nidarosiensis and Leucoraja circu- Update on Eleven Rare Cartilaginous laris), Squaliformes (Centrophorus uyato, Dalatias licha and Oxynotus centrina) and Torpediniformes Fish in the Central-Western (Tetronarce nobiliana), useful for their assessment and for future management actions. -

18 Rays & Skates

#18 Rays & Skates Blue-spotted stingray (Dasyatis kuhlii) Spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus ocellatus) Species & Distribution Habitats & Feeding There are several hundred species of fi sh commonly known Most species are adapted for life on the sea fl oor and can as skates, stingrays and eagle rays. They are similar to take in water through large openings called spiracles, rather sharks in that they have a skeleton made of tough, elastic than through the mouth as most fi sh do. Most species feed material rather than bone, but have fl attened bodies and on soft sandy sea fl oors though eagle rays often swim up in wing-like side fi ns (pectoral fi ns). the water column, as do giant manta rays. These “wings” which provide most of the edible meat do Most species have heavy, rounded teeth for crushing the not contain the soup needles (or fi nrays) found in sharks shells of bottom-dwelling species such as sea snails, clams, so they are not as sought after as sharks in the overfi shed oysters and crabs. They also eat worms, shrimps and some sharkfi n fi shery. fi sh. The related manta ray, however, fi lters small animals (plankton) from the water. Several species are used as food across the Pacifi c and the spotted eagle ray, Aetobatus ocellatus, and the blue-spotted The main predators of smaller stingrays in tropical waters stingray, Dasyatis kuhlii, are used here as examples. The are sharks and large species of fi sh. spotted eagle ray, which has many white spots on a dark blue/ green body and a wingspan width of 2.5 metres, is common throughout the entire tropical Indo-Pacifi c. -

ZOOLIGHTS Nov

ZOOLIGHTS Nov. 24 - Jan. 1 Hammerheads! Swim into a Sea Winter Break is Eagle Rays! of Zoolights made for camp Sea Turtles! pages 4-5 page 7 page 2 POINT DEFIANCE ZOO & AQUARIUM | TACOMA, WASHINGTON | WINTER 2017 ‘I GO HOME EVERY NIGHT THINKING ABOUT THEM’ Dedicated aquarists care for hammerhead sharks, eagle rays and sea turtles as aquarium completion nears The animals began arriving toward The aquarium team is establishing the end of the summer – sharks and relationships of trust with the graceful, eagle rays from a sustainable fishery winged eagle rays, which love whole in Hawaii; green sea turtles Sunny and clams as well as squid; and with the Azul from SeaWorld San Diego. turtles, eaters of romaine lettuce, other Though the scalloped hammerheads vegetables and pieces of seafood. are endangered around the world as Once in their Baja Bay home, a species, they are plentiful in Hawaii. each animal will have its own spot So are the eagle rays. Both species met for feeding. Hawaiian regulations for transport to And all will be ambassadors for an out-of-state aquarium. The sea turtles, their wild counterparts, helping Point Looking down on their 26,700-gallon, hatched at Sea World in 2003, are not 40-foot-long-by-20-foot-wide temporary Defiance Zoo & Aquarium visitors learn releasable to the wild, according to the about the threats to the world’s ocean home, Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. staff aquarist Melissa Bishop watches and the animals that live there—and several young scalloped hammerhead Aquarists, architects, engineers, the steps each of us can take to save sharks glide smoothly through the plumbers, electricians and others our seas. -

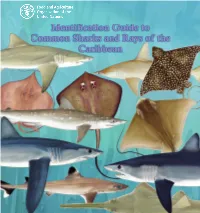

Identification Guide to Common Sharks and Rays of the Caribbean

Identification Guide to Common Sharks and Rays of the Caribbean The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2016 ISBN 978-92-5-109245-3 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Field Guide for the Identification of Major Demersal Fishes of India

Field Guide for the identification of major demersal fishes of India Rekha J. Nair and P.U Zacharia Demersal Fisheries Division, CMFRI, Kochi -682018 [email protected] Capture fisheries and aquaculture supplied the world with 142 million tonnes of fish in 2008 (SOFIA, 2010) of which 79.9 mt was contributed by marine capture fisheries. In India, demersal fishery resources contributed to about 28 % of the total estimated landings of 3.16 million tonnes. The major demersal fish resources of the country are elasmobranchs, perches, croakers, catfishes, lizard fishes, silverbellies and flatfishes. Elasmobranchs: Fishery is constituted by sharks, rays and skates. They belong to Class Chondrichthys. ) 51 families, 178 genera, 937 species of extant elasmobranchs (ie around 403 sps of sharks & 534 sps of skates and rays) ) 28 species of sharks and rays are known from freshwater. ) In India - ) 110 species of elasmobranchs - 66 species of sharks, 4 saw fishes, 8 guitar fishes and 32 rays ) 34 species are commercially important. 1 Phylum: Chordata Class Elasmobranchii Order Carcharhiniformes 9 Family Carcharhinidae - (Requiem sharks) ) one of the largest and most important families of sharks ) eyes circular ) nictitating eyelids internal; spiracles usually absent. ∗ Genus : Carcharhinus Small to large sharks with round eyes, internal nictitating eyelids, usually no spiracles. Teeth usually blade like with one cusp. Development usually viviparous with young born fully developed. Includes several dangerous species. Carcharhinus brevipinna – Spinner shark Conspicuous white band on sides. Second dorsal, anal, undersides of pectorals and lower caudal fin lobe black or dark grey-tipped; dorsal origin behind pectoral fin Carcharhinus limbatus – Black tip shark Black tip persistent on pelvic; dorsal origin at posterior end of pectoral. -

Spatial and Seasonal Variation in a Target Fishery for Spotted Eagle Ray

Fish Sci DOI 10.1007/s12562-011-0389-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Fisheries Spatial and seasonal variation in a target fishery for spotted eagle ray Aetobatus narinari in the southern Gulf of Mexico Elizabeth Cuevas-Zimbro´n • Juan Carlos Pe´rez-Jime´nez • Iva´nMe´ndez-Loeza Received: 15 October 2010 / Accepted: 6 July 2011 Ó The Japanese Society of Fisheries Science 2011 Abstract The target fishery for the spotted eagle ray Keywords Spotted eagle ray Á Artisanal fishery Á Landing Aetobatus narinari in the southern Gulf of Mexico is little trends Á Fleet dynamics Á Gulf of Mexico known. The landings of four small-scale vessels at two fishing localities were sampled and fishermen were inter- viewed in 2009. Rays landed at Campeche [mean ± stan- Introduction dard deviation (SD) 1204 ± 225.3 mm disc width (DW)], fished at 30–50 km from the shore, were larger than rays The spotted eagle ray Aetobatus narinari is a large-sized landed at Seybaplaya (924 ± 206.5 mm DW), fished at ray (230 cm disc width, DW) distributed in tropical and 8–15 km from the shore. Ray catches were male biased off warm-temperate coastal areas of all oceans [1]. Recent Campeche and female biased off Seybaplaya. Catch rate molecular studies have revealed that genetic exchange off Campeche was 6.6 (±4.9) rays per vessel trip and off among ocean basins is highly restricted and that A. nari- Seybaplaya was 3.0 (±2.9) rays per vessel trip. Fishermen nari should be considered to be a species complex rather stated that catches of A. -

Updated Species List for Sharks Caught in Iccat Fisheries

SCRS/2014/027 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 71(6): 2557-2561 (2015) UPDATED SPECIES LIST FOR SHARKS CAUGHT IN ICCAT FISHERIES Paul de Bruyn1 and Carlos Palma 1 SUMMARY This document presents a brief discussion of the increasing list of species being reported to the ICCAT secretariat, together with a proposal for complete taxonomic classification aimed to be revised and approved by the Sharks Working Group. RÉSUMÉ Ce document présente une brève discussion sur la liste croissante des espèces qui sont déclarées au Secrétariat de l'ICCAT, conjointement avec une proposition visant à ce que le Groupe d'espèces sur les requins révise et approuve une classification taxonomique complète. RESUMEN Este documento presenta un breve debate sobre la lista cada vez mayor de especies que se comunican a la Secretaría de ICCAT, junto con una propuesta para completar la clasificación taxonómica con miras a su revisión y aprobación por el Grupo de especies sobre tiburones. KEYWORDS Sharks, Rays, Taxonomy Overview of ICCAT species According to the ICCAT website (http://www.iccat.int/en/introduction.htm), about 30 species are of direct concern to ICCAT: Atlantic bluefin (Thunnus thynnus thynnus), skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis), yellowfin (Thunnus albacares), albacore (Thunnus alalunga) and bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus); swordfish (Xiphias gladius); billfishes such as white marlin (Tetrapturus albidus), blue marlin (Makaira nigricans), sailfish (Istiophorus albicans) and spearfish (Tetrapturus pfluegeri); mackerels such as spotted Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus) and king mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla); and, small tunas like black skipjack (Euthynnus alletteratus), frigate tuna (Auxis thazard), and Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda). Through the Convention, it is established that ICCAT is the only fisheries organization that can undertake the range of work required for the study and management of tunas and tuna-like fishes in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas.