Brandon Belt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlanta Braves (24-25) Vs

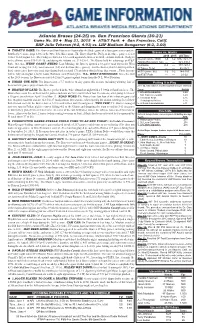

Atlanta Braves (24-25) vs. San Francisco Giants (30-21) Game No. 50 May 31, 2015 AT&T Park San Francisco, Calif. RHP Julio Teheran (4-2, 4.91) vs. LHP Madison Bumgarner (6-2, 3.00) TODAY’S GAME: The Braves and San Francisco Giants play the fi nale game of a four-game series and the fourth of seven meetings between the two clubs this season...The Braves host the Dodgers in a three-game series at Braves vs. Giants Turner Field August 3-5...The Dodgers claimed a 1-5 record against the Braves in 2014...Atlanta trails the Dodgers 2014 2015 All-Time Overall (since 1900) 1-5 1-2 935-1121-18 in the all-time series 935-1121-18, and during the Atlanta era, 321-330-1...The Giants hold the advantage at AT&T Atlanta Era (since ‘66) --- --- 321-330-1 Park, 183-144...WEST COAST SWING: Last Monday, the Braves opened a 10-game road trip to the West at Atlanta 0-3 --- 177-147-1 Coast at Los Angeles (1-2), San Francisco (1-2) and Arizona (three games)...For the Braves, this 10-day trip is their at Turner Field -- --- 42-25-1 third consecutive three-city road trip (dating back to April 17) and their third of four this season ...Their last one at SF (since ‘66) 1-2 1-2 144-183 will be July 24-August 2, to St. Louis, Baltimore and Philadelphia...N.L. WEST STRUGGLES: Since the start at AT&T Park --- --- 21-32 of the 2014 season, the Braves are just 14-25 in 39 games against teams from the N.L. -

Believe: the Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" by David J

Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" By David J. Fletcher, CBM President Posted Sunday, April 12, 2015 Disheartened White Sox fans, who are disappointed by the White Sox slow start in 2015, can find solace in Sunday night’s television premiere of “Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" that airs on Sunday night April 12th at 7pm on Comcast Sports Net Chicago. Produced by the dynamic CSN Chi- cago team of Sarah Lauch and Ryan Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox will air McGuffey, "Believe" is an emotional on Sunday, Apr. 12 at 7:00pm CT, on Comcast Sportsnet. roller-coaster-ride of a look at a key season in Chicago baseball history that even the casual baseball fan will enjoy because of the story—a star-crossed team cursed by the 1919 Black Sox—erases 88 years of failure and wins the 2005 World Series championship. Lauch and McGuffey deliver an extraordinary historical documentary that includes fresh interviews with all the key participants, except pitcher Mark Buehrle who declined. “Mark respectfully declined multiple interview requests. (He) wanted the focus to be on his current season,” said McGuffey. Lauch did reveal “that Buehrle’s wife saw the film trailer on the Thursday (April 9th) and loved it.” Primetime Emmy & Tony Award winner, current star of Showtime’s acclaimed drama series “Homeland”, and lifelong White Sox fan Mandy Patinkin, narrates the film in an under-stated fashion that retains a hint of his Southside roots and loyalties. The 76 minute-long “Believe” features all of the signature -

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

06-21-2012 Lineup.Indd

Los Angeles Dodgers vs. Oakland Athletics · Thursday, June 21, 2012 · 12:35 pm · CSNCA GAME SCORECARD First Pitch: Time of Game: Attendance: Today’s Umpires: About Today’s Game: Offi cial Scorer: Art Santo Domingo HP 55 Angel Hernandez* Throwback Thursday giveaway: A’s scorecard and bag of peanuts (10,000 fans) 1B 98 Chris Conroy A’s Upcoming Games: 2B 15 Ed Hickox June 22 SF RHP Jarrod Parker (3-3, 2.82) vs. RHP Tim Lincecum (2-8, 6.19) 7:05 pm CSNCA 3B 6 Mark Carlson June 23 SF RHP Tyson Ross (2-6, 6.11) vs. LHP Madison Bumgarner (8-4, 2.92) 4:15 pm FOX *Crew chief June 24 SF RHP Brandon McCarthy (6-3, 2.54) vs. RHP Matt Cain (9-2, 2.34) 1:05 pm CSNCA LOS ANGELES DODGERS (42-27) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AB R H RBI 9 Dee GORDON, SS (L) (.228, 1, 15) 37 Elian HERRERA, LF (S) (.283, 0, 14) 16 Andre ETHIER, RF (L) (.286, 10, 55) 21 Juan RIVERA, 1B (.240, 3, 21) 6 Jerry HAIRSTON JR., 2B (.311, 2, 16) 13 Ivan DE JESUS, DH (.310, 0, 4) 5 Juan URIBE, 3B (.240, 1, 12) 10 Tony GWYNN JR., CF (L) (.257, 0, 17) 18 Matt TREANOR, C (.295, 2, 7) LOS ANGELES ROSTER PITCHERS IP H R ER BB SO HR Pitches Coaching Staff: 8 Don Mattingly, Manager 22 LHP Clayton KERSHAW (5-3, 2.86) 45 Trey Hillman, Bench 40 Rick Honeycutt, Pitching 25 Dave Hansen, Hitting 43 Ken Howell, Bullpen 15 Davey Lopes, First Base 26 Tim Wallach, Third Base Bench: Bullpen: Left Left 3 Adam Kennedy IF 35 Chris Capuano SP 7 James Loney IF 57 Scott Elbert RP 23 Bobby Abreu OF Right Right 28 Jamey Wright RP 17 A.J. -

San Francisco Giants Weekly Notes: April 13-19

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS WEEKLY NOTES: APRIL 13-19 Oracle Park 24 Willie Mays Plaza San Francisco, CA 94107 Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com sfgigantes.com giantspressbox.com @SFGiants @SFGigantes @SFGiantsMedia NEWS & NOTES RADIO & TV THIS WEEK The Giants have created sfgiants.com/ Last Friday, Sony and the MLBPA launched fans/resource-center as a destination for MLB The Show Players League, a 30-player updates regarding the 2020 baseball sea- eSports league that will run for approxi- son as well as a place to find resources that mately three weeks. OF Hunter Pence will Monday - April 13 are being offered throughout our commu- represent the Giants. For more info, see nities during this difficult time. page two . 7:35 a.m. - Mike Krukow Fans interested in the weekly re-broadcast After crowning a fan-favorite Giant from joins Murph & Mac of classic Giants games can find a schedule the 1990-2009 era, IF Brandon Crawford 5 p.m. - Gabe Kapler for upcoming broadcasts at sfgiants.com/ has turned his sights to finding out which joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks fans/broadcasts cereal is the best. See which cereal won Tuesday - April 14 his CerealWars bracket 7:35 a.m. - Duane Kuiper joins Murph & Mac THIS WEEK IN GIANTS HISTORY 4:30 p.m. - Dave Flemming joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks APR OF Barry Bonds hit APR On Opening Day at APR Two of the NL’s top his 661st home run, the Polo Grounds, pitchers battled it Wednesday - April 15 13 passing Willie Mays 16 Mel Ott hit his 511th 18 out in San Francis- 7:35 a.m. -

San Francisco Giants

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2016 END OF SEASON NOTES 24 Willie Mays Plaza • San Francisco, CA 94107 • Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com • sfgigantes.com • sfgiantspressbox.com • @SFGiants • @SFGigantes • @SFG_Stats THE GIANTS: Finished the 2016 campaign (59th in San Francisco and 134th GIANTS BY THE NUMBERS overall) with a record of 87-75 (.537), good for second place in the National NOTE 2016 League West, 4.0 games behind the first-place Los Angeles Dodgers...the 2016 Series Record .............. 23-20-9 season marked the 10th time that the Dodgers and Giants finished in first and Series Record, home ..........13-7-6 second place (in either order) in the NL West...they also did so in 1971, 1994 Series Record, road ..........10-13-3 (strike-shortened season), 1997, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2012, 2014 and 2015. Series Openers ...............24-28 Series Finales ................29-23 OCTOBER BASEBALL: San Francisco advanced to the postseason for the Monday ...................... 7-10 fourth time in the last sevens seasons and for the 26th time in franchise history Tuesday ....................13-12 (since 1900), tied with the A's for the fourth-most appearances all-time behind Wednesday ..................10-15 the Yankees (52), Dodgers (30) and Cardinals (28)...it was the 12th postseason Thursday ....................12-5 appearance in SF-era history (since 1958). Friday ......................14-12 Saturday .....................17-9 Sunday .....................14-12 WILD CARD NOTES: The Giants and Mets faced one another in the one-game April .......................12-13 wild-card playoff, which was added to the MLB postseason in 2012...it was the May .........................21-8 second time the Giants played in this one-game playoff and the second time that June ...................... -

Anderson Goes 4, Tribe Hitless for 7 1/3 in Loss by Chris Gabel / Special to MLB.Com | March 11Th, 2016 SCOTTSDALE, Ariz

Anderson goes 4, Tribe hitless for 7 1/3 in loss By Chris Gabel / Special to MLB.com | March 11th, 2016 SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. -- Five Rockies pitchers held the Indians without a baserunner for 7 1/3 innings Friday in a 6-1 Colorado victory at Salt River Fields. Chad Bettis, Christian Bergman, Jason Motte, Miguel Castro and Scott Oberg combined to set down the first 22 Indians -- in a lineup that featured at least six Opening Day starters -- before Mike Napoli drew a walk on a full-count pitch. Adam Moore then broke up the no-hitter with a double to deep center field. Bettis set the tone in his first start of Spring Training. In contention to start on Opening Day, the right-hander induced five groundouts and struck out three. Bergman struck out three in his two innings and Motte and Castro were perfect in their one inning apiece. The Indians broke up the shutout on Zack Walters' infield single to score Napoli. But the Rockies already up six runs by that point. "Guys threw the ball really well," manager Walt Weiss said. "We were good off the mound today. Really good. That's a good sign." He added: [Bettis] was in complete control." The Rockies got on the board in the third inning against Indians starter Cody Anderson.Daniel Descalso and Rafael Ynoa led off with back- to-back singles, followed by an RBI groundout from Charlie Blackmon. Colorado added a run in the fourth, when newly signedRyan Raburn singled and Brandon Barnes doubled to deep center field. -

Describing Baseball Pitch Movement with Right-Hand Rules

Computers in Biology and Medicine 37 (2007) 1001–1008 www.intl.elsevierhealth.com/journals/cobm Describing baseball pitch movement with right-hand rules A. Terry Bahilla,∗, David G. Baldwinb aSystems and Industrial Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0020, USA bP.O. Box 190 Yachats, OR 97498, USA Received 21 July 2005; received in revised form 30 May 2006; accepted 5 June 2006 Abstract The right-hand rules show the direction of the spin-induced deflection of baseball pitches: thus, they explain the movement of the fastball, curveball, slider and screwball. The direction of deflection is described by a pair of right-hand rules commonly used in science and engineering. Our new model for the magnitude of the lateral spin-induced deflection of the ball considers the orientation of the axis of rotation of the ball relative to the direction in which the ball is moving. This paper also describes how models based on somatic metaphors might provide variability in a pitcher’s repertoire. ᭧ 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Curveball; Pitch deflection; Screwball; Slider; Modeling; Forces on a baseball; Science of baseball 1. Introduction The angular rule describes angular relationships of entities rel- ative to a given axis and the coordinate rule establishes a local If a major league baseball pitcher is asked to describe the coordinate system, often based on the axis derived from the flight of one of his pitches; he usually illustrates the trajectory angular rule. using his pitching hand, much like a kid or a jet pilot demon- Well-known examples of right-hand rules used in science strating the yaw, pitch and roll of an airplane. -

SPARTAN DAILY Chair of SJSU’S Anthropology Depart- in Fair Detail, and Gets Publicized in Ment

Softball CD REVIEW Team wins 25th game Did musician against Santa Clara channel Hendrix? SEE PAGE 6 SEE PAGE 4 Serving San José State University since 1934 Wednesday, April 7, 2010 www.TheSpartanDaily.com Volume 134, Issue 33 Candidates for opening of dean position visit campus Daniel Herberholz but with an awful lot of guidance from Staff Writer the provost’s offi ce,” Darrah said. In December, the position’s search The dean of the College of Social committee began publicizing the open Sciences will step down at the end of position across the country, he said, this semester, and the four fi nalists including in the Chronicle for Higher selected for the dean’s position will Education, which Darrah called the be visiting the campus during the fi rst “Wall Street Journal for academics.” two weeks after spring recess, said the “There’s an announcement for chair of the position’s search commit- the position that is written up that is tee. very, very detailed and very specifi c “Dr. (Tim) Hegstrom is retiring ... about what we want in the position Tuesday’s Coffee Night at the International House brought local and international students alike to meet new and he’s been a very successful dean,” of dean, what abilities we want him and old friends. Nat Eveans of Australia announces the start of an egg hunt Tuesday night at the house’s dining said Charles Darrah, who is also the to have,” Darrah said. “It’s spelled out room. KIRSTEN AGUILAR / SPARTAN DAILY chair of SJSU’s anthropology depart- in fair detail, and gets publicized in ment. -

BULLDOG BASEBALL 19 Akron

SEASON SCHEDULE/RESULTS MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY FEBRUARY 18 Akron ...................................... W, 11-0 Jones career-hi 7.0 IP, Bradford 3-4 19 Lamar ...................................... W, 2-0 Stratton career-hi 10 Ks BULLDOG BASEBALL 19 Akron ...................................... W, 10-1 Norris 3x5, 5 RBI Week 13 • Games 49-51: May 12-14 MVSU & Ole Miss 20 Lamar .................................... W, 17-2 13-run 1st, Ogden 1st grand slam — Mississippi 22 Northwestern State ................. W, 6-4 Freeman 3 hits, Bradford 3 RBI DOGS CONTINUE ROAD WORK AT OLE MISS State’s late-season road run makes a stop in Oxford, Miss., with this week’s key 25 Belmont .................................... L, 1-2 Jones car.-hi 8+ IP; BU-2R ITP-HR in 9th three-game SEC Western Division showdown with instate league rival Ole Miss 26 Belmont ................................... W, 5-3 Stratton career-hi 13 Ks, Ogden HR #3 (27-21/11-13 SEC). The 27 Belmont ..................................W, 14-5 Mitchell earns win in 1st car. start Bulldogs (30-18, 11-13), COMPARING MARCH winners of a season-best MSU THE STATS UM 1 Alcorn State ............................. W, 8-1 Graveman car.-hi 7 Ks, 12 hits, all singles six consecutive games, are 30-18 Overall record 27-21 11-13 Conference 11-13 4 Iowa ........................................... L, 3-5 Out-scored 4-2 after 2-hr. rain delay in the middle of a stretch 5 Georgia State ...........................W, 8-1 Stratton win No. 3, Bradford 3 RBI .290 Batting average .281 that sends the Diamond 6.4 Runs per game 5.6 5 Iowa ...........................................L, 6-7 MSU rallies to trim a 7-0 defi cit Dogs on the road for eight 9.7 Hits per game 9.6 6 Georgia State ......................... -

2020 Media Guide

2020 media guide SANJACSPORTS.COM TABLETABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS 2020 BASEBALL INDIVIDUAL 2 ROSTER 20 BASEBALL RECORDS SAN JAC PLAYERS IN NO. NAME POSITION B/T HT. WT. YR. HOMETOWN / HIGH SCHOOL / OR PREVIOUS COLLEGE PLAYER BIOS 1 Raymond Torres Jr. C S/R 5-11 187 Fresh. Charlotte, NC /Home School / IMG 3 PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL 2 Hunter Townsend OF R/R 6-0 200 Soph. Alto, Texas / Rusk HS / Texas A&M University 24 3 Jordan Williams OF S/R 6-0 165 Fresh. Odessa, Fla. / Home School 5 Alan Shibley INF L/R 6-0 180 Fresh. Sapulpa, Okla. / Sapulpa HS 6 Tyriece Silas OF L/L 5-11 182 Soph. Houston, Texas / Cypress Falls HS 7 Cole Turney OF L/L 6-0 200 Soph. Richmond, Texas / Travis HS / Arkansas 8 Zach Limas INF R/R 5-8 160 Soph. Richmond, Texas / Foster HS IN THE COMMUNITY 9 Jonathan Jones RHP R/R 6-1 200 Fresh. Pearland, Texas / Manvel HS WHERE ARE THEY NOW? 10 Chase Wilkerson INF / RHP L/R 6-0 181 Soph. Headland, Ala. / Headland HS 9 11 Austin Hendrix RHP R/R 5-11 210 Soph. Big Sandy, Texas / Big Sandy HS / Texas A&M University 26 12 Adam Houghtaling LHP / 1B R/R 5-11 190 Soph. Pearland, Texas /Pearland Dawson HS 13 Mitchell Parker LHP L/L 6-4 195 Soph. Albuquerque, New Mexico / Manzano HS 14 Mason Lytle OF R/R 5-11 170 Fresh. Pearland, Texas / Pearland HS 15 Antonio Valdez INF S/R 5-11 175 Soph. Corpus Christi, Texas / CC Ray HS / University of Incarnate Word ROSTER 2020 BASEBALL COACHING STAFF 16 Connor Lawrence C S/R 6-0 175 Fresh. -

Bats 3 Post-Expansion

BATS 3 POST-EXPANSION (1961-to the present) 30 teams 31 players per team 930 total players Names in red are Hall of Famers MVP Most Valuable Player league award ROY Rookie of the Year; league award. CY Cy Young winner league award; CY(M) Cy Young winner when only awarded to best pitcher in the majors NATIONAL LEAGUE MILWAUKEE-ATLANTA BRAVES ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI REDS Hank Aaron – 1971 Jay Bell – 1999 Javier Baez – 2017 Johnny Bench – 1970 MVP Felipe Alou – 1966 Eric Byrnes – 2007 Ernie Banks – 1961 Leo Cardenas – 1966 Jeff Blauser – 1997 Alex Cintron – 2003 Michael Barrett – 2006 Sean Casey – 1999 Rico Carty – 1970 Craig Counsell – 2002 Glenn Beckert – 1971 Dave Concepcion – 1978 Del Crandall – 1962 Stephen Drew – 2008 Kris Bryant – 2016 MVP Eric Davis – 1987 Darrell Evans – 1973 Steve Finley – 2000 Jody Davis – 1983 Adam Dunn – 2004 Freddie Freeman – 2017 Paul Goldschmidt – 2015 Andre Dawson – 1987 MVP George Foster – 1977 MVP Rafael Furcal – 2003 Luis Gonzalez – 2001 Shawon Dunston – 1995 Ken Griffey, Sr. - 1976 Ralph Garr – 1974 Orlando Hudson – 2008 Leon Durham – 1982 Barry Larkin – 1996 Andruw Jones – 2005 Conor Jackson – 2006 Mark Grace – 1995 Lee May – 1969 Chipper Jones – 2008 Jake Lamb – 2016 Jim Hickman – 1970 Devin Mesoraco – 2014 David Justice – 1994 Damian Miller – 2001 Dave Kingman – 1979 Joe Morgan – 1976 MVP Javier Lopez – 2003 Miguel Montero – 2009 Derrek Lee – 2005 Tony Perez – 1970 Brian McCann – 2006 David Peralta – 2015 Anthony Rizzo – 2016 Brandon Phillips – 2007 Fred McGriff – 1994 A.J. Pollock