Mauna Kea Public Access Plan January 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life in Mauna Kea's Alpine Desert

Life in Mauna Kea’s by Mike Richardson Alpine Desert Lycosa wolf spiders, a centipede that preys on moribund insects that are blown to the summit, and the unique, flightless wekiu bug. A candidate for federal listing as an endangered species, the wekiu bug was first discovered in 1979 by entomologists on Pu‘u Wekiu, the summit cinder cone. “Wekiu” is Hawaiian for “topmost” or “summit.” The wekiu bug belongs to the family Lygaeidae within the order of insects known as Heteroptera (true bugs). Most of the 26 endemic Hawaiian Nysius species use a tube-like beak to feed on native plant seed heads, but the wekiu bug uses its beak to suck the hemolymph (blood) from other insects. High above the sunny beaches, rocky coastline, Excluding its close relative Nysius a‘a on the nearby Mauna Loa, the wekiu bug and lush, tropical forests of the Big Island of Hawai‘i differs from all the world’s 106 Nysius lies a unique environment unknown even to many species in its predatory habits and unusual physical characteristics. The bug residents. The harsh, barren, cold alpine desert is so possesses nearly microscopically small hostile that it may appear devoid of life. However, a wings and has the longest, thinnest legs few species existing nowhere else have formed a pre- and the most elongated head of any Lygaeid bug in the world. carious ecosystem-in-miniature of insects, spiders, The wekiu bug, about the size of a other arthropods, and simple plants and lichens. Wel grain of rice, is most often found under rocks and cinders where it preys diur come to the summit of Mauna Kea! nally (during daylight) on insects and Rising 13,796 feet (4,205 meters) dependent) community of arthropods even birds that are blown up from lower above sea level, Mauna Kea is the was uncovered at the summit. -

Determining the Depths of Magma Chambers Beneath Hawaiian Volcanoes

Determining the Depths of Magma Chambers beneath Hawaiian Volcanoes using Petrological Methods Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science Degree At The Ohio State University By Andrew Thompson The Ohio State University 2014 Approved by Michael Barton, Advisor School of Earth Sciences Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................4 Introduction ............................................................................................... 5 Geologic Setting .......................................................................................... 6 Methods Filtering ............................................................................................ 9 CIPW Normalization ............................................................................. 11 Classification .................................................................................... 12 Results Kilauea ............................................................................................ 14 Mauna Kea ........................................................................................ 18 Mauna Loa ........................................................................................ 20 Loihi ............................................................................ ................... 23 Discussion ................................................................................................ -

Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003

“Giant of the Pacific” Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Plan of encampment on Mauna Loa summit illustrated by C. Wilkes, Engraved by N. Gimbrede (Wilkes 1845; vol. IV:155) Prepared by Dennis Dougherty B.A., Project Director Edited by J. Moniz-Nakamura, Ph. D. Principal Investigator Pacific Island Cluster Publications in Anthropology #4 National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park Department of the Interior 2004 “Giant of the Pacific” Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Prepared by Dennis Dougherty, B.A. Edited by J. Moniz-Nakamura, Ph.D. National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park P.O. Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 November, 2004 Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Executive Summary and Acknowledgements The Mauna Loa Reconnaissance project was designed to generate archival and inventory/survey level recordation for previously known and unknown cultural resources within the high elevation zones (montane, sub-alpine, and alpine) of Mauna Loa. Field survey efforts included collecting GPS data at sites, preparing detailed site plan maps and feature descriptions, providing site assessment and National Register eligibility, and integrating the collected data into existing site data bases within the CRM Division at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HAVO). Project implementation included both pedestrian transects and aerial transects to accomplish field survey components and included both NPS and Research Corporation University of Hawaii (RCUH) personnel. Reconnaissance of remote alpine areas was needed to increase existing data on historic and archeological sites on Mauna Loa to allow park managers to better plan for future projects. The reconnaissance report includes a project introduction; background sections including physical descriptions, cultural setting overview, and previous archeological studies; fieldwork sections describing methods, results, and feature and site summaries; and a section on conclusions and findings that provide site significance assessments and recommendations. -

University of Hawaii Telescopes at Mauna Kea Observatory

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII TELESCOPES AT MAUNA KEA OBSERVATORY USER MANUAL Fourth Edition, April 1996 Last modi®ed, June 1997 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 1 1.2 About this Manual :: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 1 1.3 Observing TimeÐPolicy and Procedures : :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 1 1.3.1 Students and Assistants :: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.2 Information before Arrival : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.3 Colloquia :: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.4 Reports to the Director ::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.5 Publications and Acknowledgments ::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.4 Newsletter :: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 4 1.5 Information for Visiting Observers : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 4 1.5.1 Transportation from Hilo to Hale Pohaku and Mauna Kea Observatory :: :::: ::: :::: : 4 1.6 AccommodationÐThe Mid-level Facility, Hale Pohaku :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 1.6.1 Telephone Service : :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 1.6.2 Mail Service : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 1.6.3 Library :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 2 VISITING OBSERVER EQUIPMENT 11 2.1 Packing Goods for Shipping :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 11 2.2 Transport ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: -

Hawaiian Volcanoes: from Source to Surface Site Waikolao, Hawaii 20 - 24 August 2012

AGU Chapman Conference on Hawaiian Volcanoes: From Source to Surface Site Waikolao, Hawaii 20 - 24 August 2012 Conveners Michael Poland, USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, USA Paul Okubo, USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, USA Ken Hon, University of Hawai'i at Hilo, USA Program Committee Rebecca Carey, University of California, Berkeley, USA Simon Carn, Michigan Technological University, USA Valerie Cayol, Obs. de Physique du Globe de Clermont-Ferrand Helge Gonnermann, Rice University, USA Scott Rowland, SOEST, University of Hawai'i at M noa, USA Financial Support 2 AGU Chapman Conference on Hawaiian Volcanoes: From Source to Surface Site Meeting At A Glance Sunday, 19 August 2012 1600h – 1700h Welcome Reception 1700h – 1800h Introduction and Highlights of Kilauea’s Recent Eruption Activity Monday, 20 August 2012 0830h – 0900h Welcome and Logistics 0900h – 0945h Introduction – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory: Its First 100 Years of Advancing Volcanism 0945h – 1215h Magma Origin and Ascent I 1030h – 1045h Coffee Break 1215h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1430h Magma Origin and Ascent II 1430h – 1445h Coffee Break 1445h – 1600h Magma Origin and Ascent Breakout Sessions I, II, III, IV, and V 1600h – 1645h Magma Origin and Ascent III 1645h – 1900h Poster Session Tuesday, 21 August 2012 0900h – 1215h Magma Storage and Island Evolution I 1215h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1445h Magma Storage and Island Evolution II 1445h – 1600h Magma Storage and Island Evolution Breakout Sessions I, II, III, IV, and V 1600h – 1645h Magma Storage -

HAWAII National Park HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

HAWAII National Park HAWAIIAN ISLANDS UNITED STATES RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION N AT IONAL PAR.K. SERIES n A 5 o The world-famed volcano of Kilauea, eight miles in circumference An Appreciation of the Hawaii National Park By E. M. NEWMAN, Traveler and Lecturer Written Especially for the United States Railroad Administration §HE FIRES of a visible inferno burning in the midst of an earthly paradise is a striking con trast, afforded only in the Hawaii National Park. It is a combination of all that is terrify ing and all that is beautiful, a blending of the awful with the magnificent. Lava-flows of centuries are piled high about a living volcano, which is set like a ruby in an emer ald bower of tropical grandeur. Picture a perfect May day, when glorious sunshine and smiling nature combine to make the heart glad; then multiply that day by three hundred and sixty-five and the result is the climate of Hawaii. Add to this the sweet odors, the luscious fruits, the luxuriant verdure, the flowers and colorful beauty of the tropics, and the Hawaii National Park becomes a dreamland that lingers in one's memory as long as memory survives. Pa ae three To the American People: Uncle Sam asks you to be his guest. He has prepared for you the choice places of this continent—places of grandeur, beauty and of wonder. He has built roads through the deep-cut canyons and beside happy streams, which will carry you into these places in comfort, and has provided lodgings and food in the most distant and inaccessible places that you might enjoy yourself and realize as little as possible the rigors of the pioneer traveler's life. -

I COPV of HAWAI R SYSTEM FEB 2 3 2018

David LaS5ner UNIVERSITY President 1 I COPV of HAWAI r SYSTEM FEB 2 3 2018 February 12, 2018 ~..., . Mr. Scott Glenn, Director o 0 (X) c::o - ;o Office of Environmental Quality Control l> ...,, r .,., m Department of Health -rri rr, --i :z CD 0 State of Hawai'i -< < ,n 235 South Beretania Street, Room 702 r. :::i -N Oo Honolulu, Hawai'i 96813 :Z :;r.: -i:, < --i7::.,:;=;:-, rn -vi ·"":) Subject: Environmental Impact Statement Preparation Notice for Lancr' := 0 Authorizations for Long-Term Continuation of Astronomy on Maunakea Dear Director Glenn: The University of Hawai'i (UH) has determined at the outset that it will prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed new land authorizations for the continuation of astronomy on Maunakea. UH will prepare the EIS in accordance with the provisions and requirements of Hawai'i Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 343. Pursuant to HRS Chapter 343-S(c), an Agency Publication Form and Environmental Impact Statement Preparation Notice (EISPN) are attached. The EISPN includes a description of the requested land authorization and a brief discussion of the kinds of potential environmental impacts which will be analyzed in the forthcoming EIS. In accordance with Hawai'i Administrative Rules Chapter 11-200, we respectfully request that you publish this notice in the next available edition of The Environmental Notice for the public to submit comments to UH during the statutory 30-day public consultation period. If you have any further questions about this letter or its attachments, please contact Stephanie Nagata, Director, Office of Mauna Kea Management, at (808) 933-0734. -

Hawaiian Hotspot

V51B-0546 (AGU Fall Meeting) High precision Pb, Sr, and Nd isotope geochemistry of alkalic early Kilauea magmas from the submarine Hilina bench region, and the nature of the Hilina/Kea mantle component J-I Kimura*, TW Sisson**, N Nakano*, ML Coombs**, PW Lipman** *Department of Geoscience, Shimane University **Volcano Hazard Team, USGS JAMSTEC Shinkai 6500 81 65 Emperor Seamounts 56 42 38 27 20 12 5 0 Ma Hawaii Islands Ready to go! Hawaiian Hotspot N ' 0 3 ° 9 Haleakala 1 Kea trend Kohala Loa 5t0r6 end Mauna Kea te eii 95 ol Hualalai Th l 504 na io sit Mauna Loa Kilauea an 509 Tr Papau 208 Hilina Seamont Loihi lic ka 209 Al 505 N 98 ' 207 0 0 508 ° 93 91 9 1 98 KAIKO 99 SHINKAI 02 KAIKO Loa-type tholeiite basalt 209 Transitional basalt 95 504 208 Alkalic basalt 91 508 0 50 km 155°00'W 154°30'W Fig. 1: Samples obtained by Shinkai 6500 and Kaiko dives in 1998-2002 10 T-Alk Mauna Kea 8 Kilauea Basanite Mauna Loa -K M Hilina (low-Si tholeiite) 6 Hilina (transitional) Hilina (alkali) Kea Hilina (basanite) 4 Loa Hilina (nephelinite) Papau (Loa type tholeiite) primary 2 Nep Basaltic Basalt andesite (a) 0 35 40 45 50 55 60 SiO2 Fig. 2: TAS classification and comparison of the early Kilauea lavas to representative lavas from Hawaii Big Island. Kea-type tholeiite through transitional, alkali, basanite to nephelinite lavas were collected from Hilina bench. Loa-type tholeiite from Papau seamount 100 (a) (b) (c) OIB OIB OIB M P / e l p 10 m a S E-MORB E-MORB E-MORB Loa type tholeiite Low Si tholeiite Transitional 1 f f r r r r r r r f d y r r d b b -

SAB 009 1986 P15-32 Study Areas.Pdf

HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS 15 FIGURE 9. Study areas on the island of Hawaii STUDY AREAS forests (Figs. 9 and 16). Most rainfall is derived from We established seven study areas on Hawaii (Fig. 9): a large horizontal vortex wind pattern, but rainfall dis- Kau, an isolated montane rainforest of ohia and koa tribution resembles the convection cell pattern of pre- on the southeast slopes of Mauna Loa; Hamakua, the cipitation. The top boundary of the study area lies near windward montane rainforest of ohia and koa on Mauna the inversion layer in dry alpine scrub. Below this is Kea and Mauna Loa; Puna, the low elevation ohia well-developed wet native forest (Fig. 17). Areas de- rainforest on Kilauea; Kipukas, a high elevation dry voted to sugar cane, macadamia nuts, and cattle border scrub area on the windward side with scattered pockets the study area below and laterally. of mesic forest; Kona, the diverse leeward montane The Kau study area is relatively undisturbed by hu- area on Mauna Loa and Hualalai; Mauna Kea, the man activity, as reflected in the closed canopy cover subalpine mamane-naio woodland on Mauna Kea; and (Fig. 18). Decreasing canopy cover at higher elevations Kohala, an isolated lower elevation ohia rainforest on marks the transition to subalpine scrublands. No sta- the northern end of the island. tion had more than 20% cover of introduced trees, We established two study areas on Maui, and one introduced shrubs, or passiflora. Koa-ohia forest is the each on Molokai, Lanai, and Kauai (Figs. 10-l 1). These dominant habitat in the northeast half of the study areas are mostly in montane ohia rainforests, although area, and ohia forest elsewhere. -

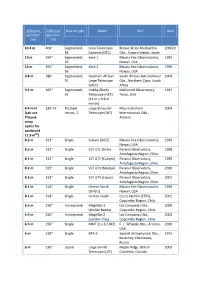

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

![Arxiv:2009.11049V2 [Astro-Ph.IM] 24 Sep 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5003/arxiv-2009-11049v2-astro-ph-im-24-sep-2020-1375003.webp)

Arxiv:2009.11049V2 [Astro-Ph.IM] 24 Sep 2020

Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics manuscript no. (LATEX: ms2020-0197.tex; printed on September 25, 2020; 1:02) The estimate of sensitivity for large infrared telescopes based on measured sky brightness and atmospheric extinction Zhi-Jun Zhao1,4, Hai-Jing Zhou1, Yu-Chen Zhang2, Yun Ling3 and Fang-Yu Xu∗2 1 School of Physics, Henan Normal University,Xinxiang 453007, China; xu [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Yunnan Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650216, China; 3 Kunming Institute of Physics, Kunming 650216, China; 4 Henan Key Laboratory of Infrared Materials & Spectrum Measures and Applications, Xinxiang 453007, China Received 20xx month day; accepted 20xx month day Abstract : In order to evaluate the ground-based infrared telescope sensitivity affected by the noise from the atmosphere, instruments and detectors, we construct a sensitivity model that can calculate limiting magnitudes and signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). The model is tested with tentative measurements of M′-band sky brightness and atmospheric extinction obtained at the Ali and Daocheng sites. We find that the noise caused by an excellent scientific detector and instruments at 135◦C can be ignored compared to the M′-band sky background noise. − Thus, when S/N =3 and total exposure time is 1 second for 10 m telescopes, the magnitude limited by the atmosphere is 13.01m at Ali and 12.96m at Daocheng. Even under less-than- − arXiv:2009.11049v2 [astro-ph.IM] 24 Sep 2020 ideal circumstances, i.e., the readout noise of a deep cryogenic detector is less than 200e and the instruments are cooled to below 87.2◦C, the above magnitudes decrease by 0.056m − at most. -

Minutes Regular Meeting Mauna Kea Management Board Wednesday

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo 640 N. A‘ohoku Place, Room 203, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720 Telephone: (808) 933-0734 Fax: (808) 933-3208 Mailing Address: 200 W. Kawili Street, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720 Minutes Regular Meeting Mauna Kea Management Board Wednesday, May 19, 2010 ʻImiloa Astronomy Center Moana Hoku Hall 600 ʻImiloa Place Hilo, Hawaii 96720 Attending MKMB: Chair Barry Taniguchi, 2nd Vice Chair/Secretary Ron Terry, John Cross, Lisa Hadway, Herring Kalua, and Christian Veillet BOR: Dennis Hirota and Eric Martinson Kahu Kū Mauna: Ed Stevens OMKM: Stephanie Nagata and Dawn Pamarang Others: Robert Albarson, Jim Albertini, Laura Aquino, Dean Au, Madeline Balo-Keawe, Sean Bassle- Kukonu, David Byrne, Rob Christensen, Gregory Chun, Nan Chun, Vaughn Cook, Sandra Dawson, Donn delaCruz, Gerald DeMello, Richard Dods, Suzanne Frayser, Paul Gillett, MRC Greenwood, Richard Ha, Katherine Hall, Cory Harden, Inge Heyer, Clyde Higashi, Nelson Ho, Arthur Hoke, Jacqui Hoover, Stewart Hunter, Stew Hussey, Leslie Isemoto, Mark Ishii, Paul Kagawa, Mike Kaleikini, Ka’iu Kimura, Kyle Kinoshita, Ron Koehler, Randy Kurohara, Susan Law, Tim Law, Karina Leasure, Jonathan Lee, Pete Lindsey, George Martin, Tani Matsubara, Jeff Melrose, Jon Miyata, Delbert Nishimoto, Eugene Nishimura, James Nixon, Cynthia Nomura, Alton Nosaka, Derek Oshita, Tom Peek, Koa Rice, Helen Rogers, Skylark Rossetti, Gary Sanders, Ian Sandison, Bill Stormont, Leonard Tanaka, Rose Tseng, Ross Watson II, Josh Williams, Ross Wilson, Greg Wines, Harry Yada, Mason Yamaki, Miles Yoshioka I. CALL TO ORDER Chair Taniguchi called the meeting of the Mauna Kea Management Board (MKMB) to order at 9:03 a.m. II. APPROVAL OF MINUTES Upon motion by Herring Kalua and seconded by Ron Terry the minutes of the April 21, 2010 meeting of the MKMB were unanimously approved.