1 Expanding the Impact of Ecolabels: Leveraging Standards to Propose Sustainable Practices for Paper Products Without Certificat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helpful Hints About Your Paper

Xerox Supplies Helpful Facts About Paper… What You Need To Know! www.tdsit.com | 479.575.0770 Helpful Facts About Paper September 2004 Xerox Corporation 2004 by Xerox Corporation. All rights reserved. Copyright protection claimed includes all forms and matters of copyrightable material and information now allowed by statutory or judicial law or hereinafter granted, including without limitation, material generated from the software programs which are displayed on the screen, such as icons, screen displays, looks, etc. Printed in the United States of America. Xerox, The Document Company, the stylized X, and all Xerox product names mentioned in this publication are trademarks of Xerox Corporation. Products and trademarks of other companies are also acknowledged. Changes are periodically made to this document. Changes, technical inaccuracies, and typographic errors will be corrected in subsequent editions. Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................1 Purpose Of This Guide.............................................................................................................................. 1 Xerox Digital Printing Systems .................................................................................................................. 2 Obtaining Optimum Performance.............................................................................................................. 2 Some Notes On Terminology ................................................................................................................... -

Digital Paper and Packaging Business Inspire and Shape a Digital World That Reinvents Quality and Productivity

2017 Edition Value Creation in the Digital Paper and Packaging Business Inspire and Shape a Digital World That Reinvents Quality and Productivity SAP Digital Paper and Packaging - 1 - © 2017 SAP SE or an SAP affiliate company. All rights reserved. ALFRED’S POINT OF VIEW Dear Industry Professional: The global paper and packaging industry is in a state of transition as it considers how to survive and thrive in this age of digital media and paperless technology. As the world population approaches 10 billion people, the rising middle class in emerging econ- omies consumes more and more hygiene products, and demand for consumer goods accelerates at an incredible pace – requiring appropriate packaging. Although this situation may sound like great news, many analysts expect paper consumption to grow at an annual rate less than 1%.1 This kind of growth can’t really provide relief to current markets, which are characterized by overcapacity and price erosion. But even this marginal growth is distributed unevenly across the globe and subsegments within the paper industry. The loss of business volume to digital media in segments like newsprint or advertising causes a severe decline in those areas. Additionally, mature markets, such as Europe and North America, show little to no growth, even for hygiene products, while global trends like Along the entire value increasing environmental regulation and volatile energy and transportation cost are shaking the chain, suppliers, paper market. producers, and packaging The consequences for the industry are dramatic. Proven business models and business plans converters will use digital based on enormous capital investments in plants and assets are collapsing. -

F I N E P a P E R S February 2 0

F i n e P a p e r s February 2 0 1 3 F i n e A r t P a p e r s T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s Paper Applications 2 - 5 DECORATIVE PAPERS Swatch Books 6 Europe / The Americas & Australia 75-91 Metric Conversion Chart 6 China 92-93 Storage Boxes 6 India 94-101 Papers for Storage 7 Japan 100-114 Korea 114 ART PAPERS Nepal 115-124 Europe / The Americas & Australia 8--41 Philippines 124 Thailand 125-131 DIGITAL PAPERS 42-44 PAPERS in ROLLS 132-135 ART PAPERS Africa 45 BOARDS 136-137 Bhutan 46-47 TRACE & GRAPH 138 China 48-49 BOOKS PADS SPIRALS 139-149 Egypt 49 India 50-52 STATIONERY 150-151 Indonesia 52 ORIGAMI 152-153 Japan 53-71 BOOKCLOTH 154-156 Nepal 72-73 Philippines 74 ADHESIVES & MOUNTING 157-159 Thailand 74 GLOSSARY 160-161 P A P E R A S S O R T M E N T P O L I C Y 25 Sheet Price - 25 - 99 sheets of one paper, one color, one weight, one size. 100 Sheet Price - 100 - 499 sheets assorted - no less than 10 sheets of each item.* 500 Sheet Price - 500 - 999 sheets assorted - no less than 25 sheets of each item.* *"Item" refers to one paper, one color, one weight, one size. I N T R O D U C T I O N / P A P E R A P P L I C A T I O N S By definition, "Paper" is a substance composed of macerated cellulose fibers first suspended in a vat of water and then re-structured into sheets by means of a mould. -

Instructions for Cataloging Paper Structures

Instructions for cataloging paper structures Vlad Atanasiu with the collaboration of Martin Haltrich Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2007 Additional material: Gerard van Thienen, Frieder Schmidt, Maria Stieglecker Images sources: Armin Renker, Das Buch vom Papier, Wiesbaden, Insel, 1951. / Therese Weber, Die Sprache des Papiers. Eine 2000-jährige Geschichte, Bern, Haupt, 2004. / Maria Zaar-Görgens, Champagne – Bar – Lothringen. Papierproduktion und Papierabsatz vom 14. bis zum Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts [Paper production and distribution from 14th to the end of the 16th century], Trier, Porta Alba, 2005. This document is also available in electronic format at: http://www.bernstein.oeaw.ac.at/twiki/pub/Main/Tutorial2007Egypt/Tutor ial_2007_Booklet.pdf. 2 Content Introduction 1. What is paper and why & how to analyze it? 1. How paper is made 2. Historical variations 3. Middle Eastern paper studies 4. Usefulness of paper studies 5. Paper analysis methods 6. Workflow for a paper catalog 2. Reproduction 1: Paper selection and reproduction 1. Identifying quires 2. Selecting remarkable papers for reproduction 3. Paper rubbings reproductions 4. Preparing a manuscript for reproduction 3. Reproduction 2: Physical measurements and image management 1. Paper width measurement 2. Metadata for the images 4. Post-processing, analysis, online databases and perspectives 1. Elements of image post-processing 2. Analyzing paper structures 3. Setting up an online database 4. Documentation 3 Introduction This booklet intends to provide the necessary information on how to produce a digital catalogue describing paper documents based on images reproducing the internal structure of the papers. Chemical and mechanical aspects of the paper, with the exception of paper width, are not covered. -

E Ink and Digital Paper

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Library Faculty and Staff papers Phillips Memorial Library January 2003 E Ink and Digital Paper Norman Desmarais Providence College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/facstaff_pubs Desmarais, Norman, "E Ink and Digital Paper" (2003). Library Faculty and Staff papers. 17. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/facstaff_pubs/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Phillips Memorial Library at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty and Staff papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. c/o Katina Strauch 209 Richardson Avenue MSC 98, The Citadel Charleston, SC 29409 SPECIAL REPRINT ™ VOLUME 14, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2002 - JANUARY 2003 ISSN: 1043-2094 “Linking Publishers, Vendors and Librarians” Innovations Affecting Us — E Ink and Digital Paper by Norman Desmarais (Acquisitions Librarian, Phillips Memorial Library, Providence College, Providence, RI 02918; Phone: 401-865-2241; Fax: 401-865-2823) <[email protected]> he main objections people have to read- embedded in their own silicone rubber sheet to Penney. The large signs (44 inches by 15 inches) ing books and documents in electronic function; but the silicone sheet could conceivably needed a very low resolution of only 2-3 dpi (dots Tformat have to do with comfort. The read- be applied to other surfaces. per inch) and were a little more than 5mm thick. ing devices, whether computer monitors or dedi- Computer monitors, by comparison, display at 70 cated devices, cause eye strain, are hard to read at E-Ink dpi and most laser printers print at 600 dpi.) The various angles and under various lighting condi- Joseph Jacobson, who was doing postdoctoral company claims its electronic paper has a resolu- tions, and lack paper’s portability and ease of research in physics at Stanford University in 1995, tion of 200 dpi which can increase to 300 dpi with use. -

Analysis of the Paperboard Industry

MARKET OPPORTUNITIES FOR LIGNOCELLULOSIC BIOMASS: ANALYSIS OF THE PAPERBOARD INDUSTRY IN THE UNITED STATES November 8, 2015 Prepared by Kusumal Ruamsook Evelyn Thomchick Center for Supply Chain Research Department of Supply Chain & Information Systems Smeal College of Business The Pennsylvania State University Copyright © 2015 by NEWBio All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Ambit of the Industry .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Scope of Products ............................................................................................................................. 8 Geographic Scope ................................................................................................................................... 10 Overview of the Paperboard Industry: Key Products and Industry Status.............................. 12 Key Product Segments: Grades and Categories .......................................................................... -

PAPER MARTINC. More Paper, More Envelopes, More Service™

PAPER MARTINC. More Paper, More Envelopes, More Service™ Digital Stocking Guide PAPER MARTINC. More Paper, More Envelopes, More Service™ 151 Ridgedale Ave East Hanover, NJ 07936 (973) 884-2505 •(800) 772-2001 www.papermartinc.com 12.11 Version 4.0 ENViRoNmENtAl lEAdER iN GREEN PRoducts ANd PRActicEs Protecting the environment has been a priority of ours for decades. Paper mart is Fsc® certified (Fsc # sGs-COC-003366) and stocks more than 5,000 green products and envelopes in-house for next day delivery. We are an industry leader in recycling practices, with a growing list of green certifications and an established Fsc 101 course that educates customers on sustainable products and practices. www.papermartinc.com • Phone: 973-884-2505 Digital Stocking Guide Table of Contents coated text and cover ...........................................................................1 cast coated .................................................................................................7 coated Board .............................................................................................9 digital opaque ...........................................................................................10 color copy ...................................................................................................18 laser multi use ...........................................................................................25 Writing, text and cover ..........................................................................26 specialty .......................................................................................................35 -

Digital Paper Handling Tips

EDUCATION SERIES DIGITAL PAPER HANDLING TIPS PAPER STORAGE AND CONDITIONING Like any other high-performance, high-quality product; a little conditioning goes a long way with digital paper. It can be the difference between ‘okay’ and ‘outstanding’ when it comes to print results! At Paper Mart, we’re proud of our digital paper selection. It’s top quality and, when properly cared for, you can expect optimal performance. While the guidelines of paper storage & handling may seem obvious, the subtle guidelines that we’ve outlined below will ensure best results. FOR OPTIMUM CONDITIONING follow these storage guidelines 1. Leave paper in its wrapper until you are ready to load it into the machine. 2. Do not store paper directly on the floor. Keep it on pallets, on shelves or in cabinets 3. Store paper at a temperature between 68°F/20°C to 76°F/24.4°C with a relative humidity between 35 to 55 percent. PAPER STACKING to avoid crushing Your paper order will normally be shipped to you in sturdy fiberboard cartons. The number of reams in each carton depends on the size and weight of the paper. If you have ordered a large quantity, the cartons will be stacked on wooden pallets. DIGITAL Stack individual reams or cartons carefully on top of one another. This will help you to avoid crushing the edges or causing any permanent damage. Pile cartons no PAPER more than five high. Pallets can be stacked three high. HANDLING PAPER HANDLING to avoid unnecessary damage TIPS Treating paper cartons with care is extremely important. -

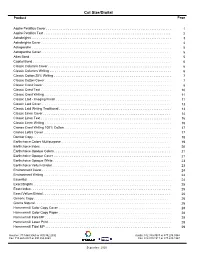

Cut Size/Digital Product Page

Cut Size/Digital Product Page Aspire Petallics Cover . 1 Aspire. Petallics. Text. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Astrobrights. 3 Astrobrights. .Cover . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 Astroparche. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Astroparche. .Cover . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Atlas. .Bond . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Capitol. .Bond . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Classic. .Columns . Cover. .. . -

Dancing with the Dark: Joan Snyder Prints 1963-2010, the First Monograph and Comprehensive Exhibition Dedicated to the Prints of This Celebrated Artist

dancing with the dark joan snyder prints 1963–2010 dancing with the dark joan snyder prints 1963–2010 Marilyn Symmes with an essay by Faye Hirsch Zimmerli Art museum At rutgers university Prestel | New yOrk copyright page TK Contents 7 Foreword and Acknowledgments Suzanne Delehanty 11 “see what a life” the prints of joan snyder Faye Hirsch 65 private/not private: an illuminated chronology of joan snyder Marilyn Symmes 151 catalogue of the prints Marilyn Symmes with Joan Snyder and Mira Dancy 167 Notes 171 Selected Bibliography 173 Index 176 Zimmerli Art Museum Staff 176 Zimmerli Art Museum Staff 176 Lenders? Frontispiece Altar, 2010. Digital print, color lithograph, chine collé, color etching, color woodcut (printed in the manner of an intaglio) and collograph; 85.7 x 80 cm 3 1 (33 ⁄4 x 31 ⁄2 in.). Collection of the artist (cat. 68) Foreword and Acknowledgments In 1963, an aspiring artist and art student at Rutgers University made her first prints. Nearly five decades later, she has become a nationally recognized artist, a 2007 MacArthur Fellow, and the creator of an admirable body of work, and those early prints, along with many others, have returned to Rutgers. The Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers is proud to present Dancing with the Dark: Joan Snyder Prints 1963-2010, the first monograph and comprehensive exhibition dedicated to the prints of this celebrated artist. While there have been a number of exhibitions and catalogues about her paintings, Snyder’s prints are less well known. This project surveys the extraordinary range of her graphic achievement and her significant contributions to American printmaking. -

An Analysis of the Factors Influencing Paper Selection for Books of Reproduced Fine Art Printed on Digital Presses

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Books 2012 An Analysis of the factors influencing paper selection for books of reproduced fine ra t printed on digital presses Brian M. Gamm Franziska Frey Susan Farnand Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/books Recommended Citation Gamm, Brian M.; Frey, Franziska; and Farnand, Susan, "An Analysis of the factors influencing paper selection for books of reproduced fine ra t printed on digital presses" (2012). Accessed from http://scholarworks.rit.edu/books/99 This Full-Length Book is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Analysis of the Factors Influencing Paper Selection for Books of Reproduced Fine Art Printed on By Brian M. Gamm Digital Presses Graduate Student, Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science Franziska Frey, Ph.D. McGhee Distinguished Professor, School of Print Media Susan Farnand A Research Monograph of the Staff Scientist, Chester F. Carlson Printing Industry Center at RIT Center for Imaging Science No. PICRM-2012-02 Rochester Institute of Technology An Analysis of the Factors Influencing Paper Selection for Books of Reproduced Fine Art Printed on Digital Presses By Brian M. Gamm Graduate Student, Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science Rochester Institute of Technology Franziska Frey, Ph.D. McGhee Distinguished Professor, School of Print Media Rochester Institute of Technology Susan Farnand Staff Scientist, Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science Rochester Institute of Technology A Research Monograph of the Printing Industry Center at RIT Rochester, NY November 2011 PICRM-2012-02 © 2012 Printing Industry Center at RIT— All rights reserved. -

An Investigation Into Papers for Digital Printing

An Investigation into Papers for Digital Printing By Mary Anne Evans, Ph.D. Professor, School of Print Media Bernice A. LeMaire Graduate Student, School of Print Media Rochester Institute of Technology A Research Monograph of the Printing Industry Center at RIT No. PICRM-2005-06 An Investigation into Papers for Digital Printing By Mary Anne Evans Ph.D. Professor, School of Print Media Rochester Institute of Technology Bernice A. LeMaire Graduate Student, School of Print Media Rochester Institute of Technology A Research Monograph of the Printing Industry Center at RIT Rochester, NY April 2006 PICRM-2005-06 © 2006 Printing Industry Center at RIT— All rights reserved. With Thanks The research agenda of the Printing Industry Center at RIT and the publication of research findings are supported by the following organizations: bc ii Evans & LeMaire (PICRM-2005-06) Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 Literature Review ........................................................................................................... 5 Research Objectives and Methodology ....................................................................26 Survey Results ..............................................................................................................29 Summary of Findings ..................................................................................................61