FRAMEWORK for UNDERSTANDING MOODABIDRI TEMPLES AS PUBLIC PLACES Pratyush Shankar Lecturer, Faculty of Architecture CEPT University, Ahmedabad, India January 15, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE KARNATAKA SHOPS and COMMERCIAL ESTABLISHMENTS ACT, 1961 ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS Sections : CHAPTER I

THE KARNATAKA SHOPS AND COMMERCIAL ESTABLISHMENTS ACT, 1961 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Sections : CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title, extent, commencement and application. 2. Definitions. 3. Exemptions. CHAPTER II REGISTRATION OF ESTABLISHMENTS 4. Registration of Establishments. 5. Change to be communicated to Inspector. 6. Closing of establishment to be communicated to Inspector. 6A. Issue of appointment orders. CHAPTER III HOURS OF WORK 7. Daily and weekly hours. 8. Extra wages for overtime work. 9. Interval for rest. 10. Spread over. 11. Opening and closing hours. 12. Weekly holidays. 13. Selling outside establishment prohibited after closing hours. CHAPTER IV ANNUAL LEAVE WITH WAGES 14. Application of chapter. 15. Annual leave with wages. 16. Wages during leave period. 17. Payment of advance in certain cases. GUNDU DATA BANK KARNATAKA LAW 2002 18. Mode of recovery of unpaid wages. 19. Power to make rules. 20. Power to exempt establishments. CHAPTER V WAGES AND COMPENSATION 21. Application of the Payment of Wages Act. 22. Application of the Workmens Compensation Act. 23. Omitted. CHAPTER VI EMPLOYMENT OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN 24. Prohibition of employment of children. 25. Prohibition of employment of women and young persons during night. CHAPTER VII ENFORCEMENT AND INSPECTION 26. Inspectors. 27. Powers and duties of Inspectors. 28. Inspectors to be public servants. 29. Employer to produce registers, records, etc., for inspection. CHAPTER VIII OFFENCES, PENALTIES AND PROCEDURE 30. Penalties. 31. Procedure. 32. Limitation of prosecutions. 33. Penalty for obstructing Inspectors, etc. CHAPTER IX MISCELLANEOUS 34. Maintenance of registers and records and display of notices. 35. Saving of certain rights and privileges. 36. -

A Discourse on the Deconstruction of Spirit Worship of Tulunadu

A Peer-Reviewed Refereed e-Journal Legend of Koragajja: A Discourse on the Deconstruction of Spirit Worship of Tulunadu Mridul C Mrinal MA in English and Comparative Literature Central University of Kerala, Kasaragod. The Social stratification in a community is often complex and ambiguous in nature. Upon the rise of each nation states and civilization, there were several parameters, which determined the social stratification. In ancient Greece, the word used to denote the divisions are genos. The ancient Greek society was divided into citizens, metics and slaves. In ancient Rome, the social stratification was identified with mainly two groups, Patricians and Plebeians. The chief resource for the social stratification parameters are economical in nature. Other factors such as tradition and beliefs are often can be said to have rooted in the wider economic subject. The term class is often associated with economics. There are usually hegemonial and subdued elements in social stratifications. In ancient Greece, the hegemonial element is found associated with the citizens, who are free and members of the assembly whereas slaves were the subdued element who were brought into slavery. In ancient Rome, the hegemonial element were the patricians whereas the plebeians were the subdued. These ideas can often be observed with Class struggle and historical materialism. The division of history into stages based on the relation of the classes is an important aspect of Historical materialism. In India, the main social stratification parameter is the caste.it could be claimed as ceremonial as well as economic in nature. BR Ambedkar observes Endogamy as a product of ceremonial caste. -

Franchisees in the State of Karnataka (Other Than Bangalore)

Franchisees in the State of Karnataka (other than Bangalore) Sl. Place Location Franchisee Name Address Tel. No. No. Renuka Travel Agency, Opp 1 Arsikere KEB Office K Sriram Prasad 9844174172 KEB, NH 206, Arsikere Shabari Tours & Travels, Shop Attavara 2 K.M.C M S Shabareesh No. 05, Zephyr Heights, Attavar, 9964379628 (Mangaluru) Mangaluru-01 No 17, Ramesh Complex, Near Near Municipal 3 Bagepalli S B Sathish Municipal Office, Ward No 23, 9902655022 Office Bagepalli-561207 New Nataraj Studio, Near Private Near Private Bus 9448657259, 4 Balehonnur B S Nataraj Bus Stand, Iliyas Comlex, Stand 9448940215 Balehonnur S/O U.N.Ganiga, Barkur 5 Barkur Srikanth Ganiga Somanatheshwara Bakery, Main 9845185789 (Coondapur) Road, Barkur LIC policy holders service center, Satyanarayana complex 6 Bantwal Vamanapadavu Ramesh B 9448151073 Main Road,Vamanapadavu, Bantwal Taluk Cell fix Gayathri Complex, 7 Bellare (Sulya) Kelaginapete Haneef K M 9844840707 Kelaginapete, Bellare, Sulya Tq. Udayavani News Agent, 8 Belthangady Belthangady P.S. Ashok Shop.No. 2, Belthangady Bus 08256-232030 Stand, Belthangady S/O G.G. Bhat, Prabhath 9 Belthangady Belthangady Arun Kumar 9844666663 Compound, Belthangady 08282 262277, Stall No.9, KSRTC Bus Stand, 10 Bhadravathi KSRTC Bus Stand B. Sharadamma 9900165668, Bhadravathi 9449163653 Sai Charan Enterprises, Paper 08282-262936, 11 Bhadravathi Paper Town B S Shivakumar Town, Bhadravathi 9880262682 0820-2562805, Patil Tours & Travels, Sridevi 2562505, 12 Bramhavara Bhramavara Mohandas Patil Sabha bhavan Building, N.H. 17, 9845132769, Bramhavara, Udupi Dist 9845406621 Ideal Enterprises, Shop No 4, Sheik Mohammed 57A, Afsari Compound, NH 66, 8762264779, 13 Bramhavara Dhramavara Sheraj Opposite Dharmavara 9945924779 Auditorium Brahmavara-576213 M/S G.R Tours & Travels, 14 Byndur Byndoor Prashanth Pawskar Building, N.H-17, 9448334726 Byndoor Sl. -

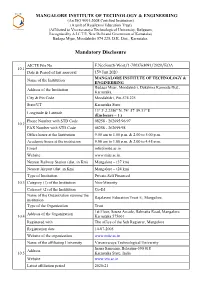

Mandatory Disclosure

MANGALORE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & ENGINEERING (An ISO 9001:2008 Certified Institution) (A unit of Rajalaxmi Education Trust) (Affiliated to Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belgaum, Recognised by A.I.C.T.E, New Delhi and Government of Karnataka) Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri 574 225, D.K. Dist., Karnataka. Mandatory Disclosure AICTE File No. F.No.South-West/1-7003763091/2020/EOA 10.1 Date & Period of last approval th 15 Jun 2020 MANGALORE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & Name of the Institution ENGINEERING Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri, Dakshina Kannada Dist., Address of the Institution Karnataka. City & Pin Code Moodabidri, Pin-574 225 State/UT Karnataka State 13° 3' 2.2356'' N, 74° 57' 59.31'' E Longitude & Latitude (Enclosure – 1 ) Phone Number with STD Code 08258 - 262695/96/97 10.2 FAX Number with STD Code 08258 - 262699/98 Office hours at the Institution 9.00 am to 1.00 p.m. & 2.00 to 5.00 p.m. Academic hours at the institution 9.00 am to 1.00 p.m. & 2.00 to 4.45 p.m. Email [email protected] Website www.mite.ac.in Nearest Railway Station (dist. in Km) Mangalore – (37 km) Nearest Airport (dist. in Km) Mangalore – (24 km) Type of Institution Private-Self Financed 10.3 Category (1) of the Institution Non-Minority Category (2) of the Institution Co-Ed Name of the Organization running the Rajalaxmi Education Trust ®, Mangalore. institution Type of the Organization Trust 1st Floor, Souza Arcade, Balmatta Road, Mangalore, Address of the Organization 10.4 Karnataka 575001 Registered with The office of the Sub Registrar, Mangalore Registration date 14-07-2005 Website of the organization www.mite.ac.in Name of the affiliating University Visvesvaraya Technological University Jnana Sangama, Belgaum-590 018 Address 10.5 Karnataka State, India Website www.vtu.ac.in Latest affiliation period 2020-21 Name of Principal / Director Dr. -

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY Detailed Information of All India Inter

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY Accredited by NAAC with ‘A’ Grade DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION Dr. Kishore Kumar C K Mangalagangotri 574 199 Director of Physical Education DK Dist., Karnataka State Organizing Secretary Phone :0824-2287 265(0) Mobile:9448178402 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ No.MU/DPE/ 485/2015-16 Date:04.09.2015 To The Registrar/Director of Physical Education/ Secretary, Sports Board Universities Affiliated to AIU Sir, Sub: Regarding conducting of All India Inter-University Cross Country Championship (Men and Women) for the year 2015-16 Reg. We are pleased to inform you that the Association of Indian Universities, New Delhi, has entrusted the responsibility of organizing the All India Inter-University Cross Country Championship for Men and Women for the year 2015-16 to Mangalore University, Mangalore, Karnataka and we are hosting the championship on 11th October 2015 at Alva's College, Moodabidri -574227, Dakshina Kannada District, Karnataka. On behalf of Prof. K. Byrappa, Hon'ble Vice Chancellor of Mangalore University and the Organizing committee, I extend a warm welcome to all the Universities affiliated to AIU to participate in the above event. Detailed Information of All India Inter-University Cross country Championship for Men and Women 2015-16 1. Venue of the Competition The competition will be held at Alva’s College, Vidyagiri Campus, Moodabidri, Dakshina Kannada District, Karnataka, an affiliated college of Mangalore University, situated about 32 Kilometres from Mangalore Railway station and Mangalore City. 2. Date of the Competition: The All India Inter-University Cross Country Championship for Men and Women will be held 11th October 2015. (Reporting date is 10th, October 2015) 3. -

Structure and Function of Education Management Set-Up in Karnataka State

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF EDUCATION MANAGEMENT SET-UP IN KARNATAKA STATE By: A.S. Seetharamu Professor of Education Institute for Social & Economic Change Bangalore. NUEPA DC 1)11888 EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Government of Karnataka Bangalore 2002 r::7Miducational Plan ®Ufnentation Cen»® ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Government of Karnataka desired a study on "Structure and Function of Management in Education" in the State for its confidential use. The State Project Director, DPEP, acted as a liasion Officer for this and similar studies. In doing this study, my understandings of the system of educational management in the State received sharpness, focus and clarity. Through the SPD, I thank the Government for giving me this opportunity to learn and contribute to the cause of education being earnestly pursued by the Department of Education, Government of Karnataka. My thanks are due to Dr. M. Govinda Rao, Director, ISEC, who permitted me to undertake this study. Several officers of the Education Department and field workers have helped me in completion of the study. I thank all of them but mention only Mr., T.M. Vijaybhaskar, Commissioner of Public Instruction, Government of Karnataka who has also contributed to the design of the study. The meetings with all of the Officers of the DSERT was quite useful. I acknowledge the contribution of the Review Team set up by the Government for this study during Review Meetings. In particular, I may mention the name of Dr. Sajitha Bashir, World Bank, Dr. R. Govinda, NIEPA and Prof. 0. Seshadri, formerly NCERT, Mr. R.N. Shastri, I.A.S., Secretary II, Education, GOK, Smt. -

Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri 574 225, DK Dist., Karnataka

Mandatory Disclosures MANGALORE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & ENGINEERING (Sponsored by Rajalaxmi Education Trust®) Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri 574 225, D.K. Dist., Karnataka. Phone No. : (08258) 262695/96/97 Fax No. : (08258) 262699/98 Website : www.mite.ac.in E-mail : [email protected] Date: May 2015 1. Name of the Institution MANGALORE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & ENGINEERING Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri - 574 225, D.K. Dist., Karnataka. 2. Name & Address Of The Principal Dr. G.L. Easwara Prasad Principal Mangalore Institute of Technology & Engineering Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri 574 225. Telephone No. : (08258) 262698 Fax No. : (08258) 262698 E-mail : [email protected] ; [email protected] 3. Name Of The Affiliating University VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY “Jnana Sangama” Macche, Belgaum - 590 018 4. Governance Members of the Board and their brief background 1. Mr. Rajesh Chowta Chairman He is an Engineering graduate and entrepreneur. President of the Rajalaxmi Education Trust, Mangalore. 2. Mrs. Savitha Chowta Member She is a postgraduate in Sociology and also a M.Phil graduate. Vice President, Rajalaxmi Education Trust, Mangalore. 3. Prof. N.R. Shetty Member Former V.C. Bangalore University 4. Mr. Jagannath Shetty Member He is an engineer with vast years of experience. 5. Mr. Sanjeev Chowta, …. Member 6. Prof. G.R. Rai Member Former Principal of Vivekananda College of Technology, Puttur and NMAM Institute of Technology, Nitte. 7. Dr. S.M. Shashidhara .. Member (VTU Representative) He is the Principal of Kalpataru Institute of Technology, Tiptur 572202, Tumkur Dt. 8. Dr. C.R. Rajashekhar, …. Member (Faculty Representative) He is the Professor & Head, Mech. Engg. Dept. & Vice Principal, MITE., Moodbidri. -

NAIN Incubation Center Preamble

MANGALORE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND ENGINEERING (An ISO 9001: 2015 Certified Institution) (Affiliated to Visvesvaraya Technological University Belagavi) Badaga Mijar, Moodabidri-574225, Karnataka NAIN Incubation Center Preamble Do you have an idea? An Idea that could disrupt and transform. Do you aspire to be an entrepreneur? Then, you are here at the right place. We at MITE understand that entrepreneurship is the future of the global economy and have realized the shift in temperament towards self- employment. The institution is in the mission of aiding the young aspiring entrepreneurs as global forecasts say that almost one third of millennial today aspire to some form of entrepreneurial venture. MITE has set up a conducive ecosystem for the startup culture to flourish with the best infrastructure, training, and mentorship. The Entrepreneurship Development Cell strives to identify, nurture and support budding entrepreneurs. The extensive efforts of the cell have shown results with a large number of Alumni starting their independent ventures. The institution indeed takes pride in the shaping young Men & Women who aspire to change the future and be part of their journey. The institution has state-of-the-art incubation center spanning over 547 sq.m on par with industry standard. The Center has air-conditioned Office spaces, Meeting rooms and high-speed internet connectivity with the best configured computers. The incubatees are extended access to all the laboratories. The center has mentors from Industry as well as successful local entrepreneurs on- board. The Center extends technical, management and legal support to the young entrepreneurs who have just begun to take-off. -

Tourism Resources and Tourist Visitation in Selected Tourist Places

Tourism Resources and Tourist Visitation in Selected Tourist Places of Dakshina Kannada District, Karnataka – A Study Sheker Naik Department of Tourism and Travel Management, Mangalore University, Mangalagangothri Abstract Tourism is an important socio-economic and cultural activity. Today tourism resources are identified and developed with necessary tourist infrastructures throughout the world. Currently India is ranked 34th in the world out of 141 economies considered for the study by World Economic Forum in its Travel and Tourism Competitive Index Report of 2019. Tourism is gaining momentum in Karnataka, the southern state of India and the same is true in the case of Dakshina Kannada district as per as tourism resources and tourists arrivals are concerned. This study presents the digitisation important tourist attractions of the district besides making an analysis of tourist statistics during five years from 2012 to 2016. The study finds that the district has immense potential for tourism development and a lot needs to be done in order to attract the attention of more tourists to the district. Keywords: ArcGIS, Beach, Geo-reference, Tourism, Tourist. 1. Introduction Dakshina Kannada (DK) is a district in the southwestern part of coastal Karnataka. The district is sandwiched between the biological hotspot of Western Ghats in the east and the Arabian Sea in the west. The district enjoys great diversity in its physical and cultural settings. People of the districts are friendly, hospitable and honest. District has beautiful places of tourists‟ interest like temples, Basadis churches, mosques, beaches, Parks, peaks and many cultural and heritage attractions. Being in the strategic location, DK is bestowed with premier education centres and universities popularly known as educational hub of Karnataka as students from different parts of the country and abroad come here to study. -

Department of Civil Engineering

ALVA’S INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY Shobhavana Campus, Mijar, Moodabidri, Mangalore Taluk, D.K – 574225 Phone: 08258-262725, Fax: 08258-262726 DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING A BRIEF REPORT ON TECHNICAL TALK BY: B Govinda Ramesh, IIMB alumnus, Entrepreneur, Engineer-Steel Construction, Roofs and Facades, Global Effectuation Instructor, Mentor- Nerd Factory. The Civil Engineering Department of Alva’s Institute of Engineering & Technology, Mijar, organized a Inaugural function of Civiation and Technical Talk onThursday,7th September 2017 in Auditorium at 10 am, on “Effective Construction Management” By Engineer, By Govinda Ramesh PROGRAMME PROCEEDINGS : The Inauguralfunction began at 10.00 AM.The gathering was cordially welcomed byMs.Dhanya(VII Semester). Ms.Soundariya B (VII Semester) of Civil Engineering introduced the resource persons to the gathering. Prof .Durgaprasad Baliga,Head of Department, Civil Engineering, was presided over the function. Mr. Vivek Alva, Managing trusty made the presidential remark and briefed about the association. TECHNICAL TALK BY ANIL V. BALIGA MANJESHWAR A technical talk on “Effective Construction Management” presented by the resource person. SESSION CLOSURE: B GOVIND RAMESH was honored by Prof. H Ajit Hebbar. Ms. Archana (VII Semester) proposed the vote of thanks as the inaugural function came to an end. Thanks giving was done at the end of technical session by Ms. Dhanya (VII Semester). SOME PHOTOGRAPHS WITNESSING THE TECHNICAL TALK : Page 1 of 16 ALVA’S INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY Shobhavana -

Karnataka Map Download Pdf

Karnataka map download pdf Continue KARNATAKA STATE MAP Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to make this map image accurate. However, GISMAP IN and its owners are not responsible for the correctness or authenticity of the same thing. The GIS base card is available for all areas of CARNATAKA. Our base includes layers of administrative boundaries such as state borders, district boundaries, Tehsil/Taluka/block borders, road network, major land markers, places of major cities and towns, Places of large villages, Places of district headquarters, places of seaports, railway lines, water lines, etc. and other GIS layers, etc. map data can be provided in a variety of GIS formats, such as shapefile or Tab, etc. MAP DATA LAYERS DOWNLOAD You can download freely available map data for Maharashtra status in different layers and GIS formats. DOWNLOAD A MAP OF KARNATAKA COUNTY BROSWE FOR THE KARNATAKA DISTRICTS VIEW THE KARNATAKA BAGALKOT AREA CHICKMAGAL, HASSAN RAMANAGAR BANGALORE CHIKKABALLAPUR SHIMAFI CHIMOGA BANGALORE RURAL CHITRADURGA CODAGAU TUMKUR BELGAUM DAKSHINA KANNADA KAMAR UDUPI BELLARY DAVANGERE KOPPAL UTTARA KANNADA BIDAR DHARWAD MANDYA YADGIR BIJAPUR (KAR) GADAG MYSORE CHAMRAJNAGAR GULBARGA RAICHUR BROSWE FOR OTHER STATE OF INDIA Karnataka Map-Karnataka State is located in the southwestern region of India. It borders the state of Maharashtra in the north, Telangana in the northeast, Andhra Pradesh in the east, Tamil Nadu in the southeast, Kerala in the south, the Arabian Sea to the west, and Goa in the northwest. Karnataka has a total area of 191,967 square kilometres, representing 5.83 per cent of India's total land area. -

List of Trained Teachers Induction-1 Dakshina Kannada

SCHOOLWISE INDUCTION-1 TRAINED TEACHERS DETAILS OF DAKSHINA KANNADA DISTRICT IN 2016-17 slno Block Name of the School Name Sub/Designation 1 BANTWAL GHS MOUNTE PADAVU ANITHAKSHI PCM 2 BANTWAL GHS MOUNTE PADAVU CHANCHALAKSHI K CBZ 3 BANTWAL GHS MOUNTE PADAVU ZEETHA ENGLISH SOCIAL 4 BANTWAL GHS MOUNTE PADAVU JYOTHI B SCIENCE 5 BANTWAL GHS MOUNTE PADAVU SANTHOSHKUMAR TN HM GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL KALLANGALA 6 BANTWAL KEPU SUBRAHMANYA BHAT K G PCM GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL KALLANGALA 7 BANTWAL KEPU LAXMANA T NAIK CBZ GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL KALLANGALA 8 BANTWAL KEPU RAMESHA M ENGLISH GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL KALLANGALA SOCIAL 9 BANTWAL KEPU RAMESHA D SCIENCE GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL KALLANGALA 10 BANTWAL KEPU MALATHI HM GOVT HIGHSCHOOL 11 BANTWAL KOILA JYOTHI KUMARI PCM GOVT HIGHSCHOOL 12 BANTWAL KOILA SHREESHA BHAT M CBZ GOVT HIGHSCHOOL 13 BANTWAL KOILA BALAKRISHNAK ENGLISH GOVT HIGHSCHOOL SOCIAL 14 BANTWAL KOILA LAVINA D'SOUZA SCIENCE GOVT HIGHSCHOOL 15 BANTWAL KOILA SUDHEERG HM GOVT PU COLLEGE SIDDHAKATTE 16 BANTWAL (HIGHSCHOOLSECTION) SUREKHA PCM GOVT PU COLLEGE SIDDHAKATTE 17 BANTWAL (HIGHSCHOOLSECTION) POORNIMA K V CBZ GOVT PU COLLEGE SIDDHAKATTE JOSLYN LAVEENA 18 BANTWAL (HIGHSCHOOLSECTION) SEQUEIRA ENGLISH GOVT PU COLLEGE SIDDHAKATTE SOCIAL 19 BANTWAL (HIGHSCHOOLSECTION) MARGARITA PINTO SCIENCE GOVT PU COLLEGE SIDDHAKATTE 20 BANTWAL (HIGHSCHOOLSECTION) RAMANADHA HM 21 BELTHANGADI GHS Padumunja UMESH GOWDA PCM 22 BELTHANGADI GHS Padumunja RAVI KUMAR CBZ 23 BELTHANGADI GHS Padumunja MANOHARA ENGLISH SOCIAL 24 BELTHANGADI GHS Padumunja SUMATHI