A Modern Means of Resolving Water Distribution Disputes Between Israel and the Palestinians Maya Manna Roger Williams University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Israel

Sl. No River Name Draining Into 1 Nahal Betzet Mediterranean Sea 2 Nahal Kziv Mediterranean Sea 3 Ga'aton River Mediterranean Sea 4 Nahal Na‘aman Mediterranean Sea 5 Kishon River Mediterranean Sea 6 Nahal Taninim Mediterranean Sea 7 Hadera Stream Mediterranean Sea 8 Nahal Alexander Mediterranean Sea 9 Nahal Poleg Mediterranean Sea 10 Yarkon River Mediterranean Sea 11 Ayalon River Mediterranean Sea 12 Nahal Qana Mediterranean Sea 13 Nahal Shillo Mediterranean Sea 14 Nahal Sorek Mediterranean Sea 15 Lakhish River Mediterranean Sea 16 Nahal Shikma Mediterranean Sea 17 HaBesor Stream Mediterranean Sea 18 Nahal Gerar Mediterranean Sea 19 Nahal Be'er Sheva Mediterranean Sea 20 Nahal Havron Mediterranean Sea 21 Jordan River Dead Sea 22 Nahal Harod Dead Sea 23 Nahal Yissakhar Dead Sea 24 Nahal Tavor Dead Sea 25 Yarmouk River Dead Sea 26 Nahal Yavne’el Dead Sea 27 Nahal Arbel Dead Sea 28 Nahal Amud Dead Sea 29 Nahal Korazim Dead Sea 30 Nahal Hazor Dead Sea 31 Nahal Dishon Dead Sea 32 Hasbani River Dead Sea 33 Nahal Ayun Dead Sea 34 Dan River Dead Sea 35 Banias River Dead Sea 36 Nahal HaArava Dead Sea 37 Nahal Neqarot Dead Sea 38 Nahal Ramon Dead Sea 39 Nahal Shivya Dead Sea 40 Nahal Paran Dead Sea 41 Nahal Hiyyon Dead Sea 42 Nahal Zin Dead Sea 43 Tze'elim Stream Dead Sea 44 Nahal Mishmar Dead Sea 45 Nahal Hever Dead Sea 46 Nahal Shahmon Red Sea (Gulf of Aqaba) 47 Nahal Shelomo Red Sea (Gulf of Aqaba) For more information kindly visit : www.downloadexcelfiles.com www.downloadexcelfiles.com. -

Hydro-Hegemony in the Upper Jordan Waterscape: Control and Use of the Flows Water Alternatives 6(1): 86-106

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 6 | Issue 1 Zeitoun, M.; Eid-Sabbagh, K.; Talhami, M. and Dajani, M. 2013. Hydro-hegemony in the Upper Jordan waterscape: Control and use of the flows Water Alternatives 6(1): 86-106 Hydro-Hegemony in the Upper Jordan Waterscape: Control and Use of the Flows Mark Zeitoun School of International Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK; [email protected] Karim Eid-Sabbagh School of Oriental and African Studies, Houghton Square, London; [email protected] Michael Talhami Independent researcher, Amman, Jordan; [email protected] Muna Dajani Independent researcher, Jerusalem; [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper blends the analytical framework of hydro-hegemony with a waterscape reading to explore the use and methods of control of the Upper Jordan River flows. Seen as a sub-component of the broader Lebanon-Israel-Syria political conflict, the struggles over water are interpreted through evidence from the colonial archives, key informant interviews, media pieces, and policy and academic literature. Extreme asymmetry in the use and control of the basin is found to be influenced by a number of issues that also shape the concept of 'international waterscapes': political borders, domestic pressures and competition, perceptions of water security, and other non-material factors active at multiple spatial scales. Israeli hydro-hegemony is found to be independent of its riparian position, and due in part to its greater capacity to exploit the flows. More significant are the repeated Israeli expressions of hard power which have supported a degree of (soft) 'reputational' power, and enable control over the flows without direct physical control of the territory they run through – which is referred to here as 'remote' control. -

The Blue Peace – Rethinking Middle East Water

With support from Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sweden Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Switzerland Political Affairs Div IV of the Federal Dept of Foreign Affairs, Switzerland C-306, Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West, Mumbai 400 053, India Email: [email protected] Author : Sundeep Waslekar Project Director : Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator and Principal Researcher : Ambika Vishwanath Research Analyst : Gitanjali Bakshi Creative Head : Preeti Rathi Motwani Research Advice and Review Group: Dr. Aysegul Kibaroglu (Turkey) Dr. Faisal Rifai (Syria) Dr. Marwan Haddad (Palestine Territories) Dr. Mohamed Saidam (Jordan) Prof. Muqdad Ali Al-Jabbari (Iraq) Dr. Selim Catafago (Lebanon) Eng. Shimon Tal (Israel) Project Advisory Group: Dr. Francois Muenger (Switzerland) Amb. Jean-Daniel Ruch (Switzerland) Mr. Dag Juhlin-Danfeld (Sweden) SFG expresses its gratitude to the Government of Sweden, Government of Switzerland, their agencies and departments, other supporters of the project, and members of the Research Advice and Review Group, for their cooperation in various forms. However, the analysis and views expressed in this report are of the Strategic Foresight Group only and do not in any way, direct or indirect, reflect any agreement, endorsement, or approval by any of the supporting organisations or their officials or by the experts associated with the review process or any other institutions or individuals. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2011 ISBN 978-81-88262-14-4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Hydropolitical Baseline of the Upper Jordan River

"# ! #$"%!&# '& %!!&! !"#$ %& ' ( ) *$ +,-*.+ / %&0 ! "# " ! "# "" $%%&!' "# "( %! ") "* !"+ "# ! ", ( %%&! "- (" %&!"- (( . -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

Wilshire Church Interfaith Trip to Israel 2018 October 29 – November 8, 2018 Proposed by Makor Educational Journeys

Wilshire Church Interfaith Trip to Israel 2018 October 29 – November 8, 2018 Proposed by Makor Educational Journeys Sunday, October 28, 2018 Departure from the U.S. to Israel Monday, October 29, 2018 ARRIVAL Arrive at Ben Gurion International Airport with assistance upon arrival. Meet guide and driver and drive along the Coastal Highway to Haifa. Multi-faith Welcome to Israel, overlooking the Mediterranean from atop the Bahai Gardens. Check in to the hotel. Free time for rest and relaxation. Festive Opening Dinner at the hotel. Optional walk along the Louis Promenade atop Mont Carmel. Overnight: Dan Panorama Hotel, Haifa Tuesday, October 30, 2018 A MULTICULTURAL MOSAIC Isaiah 56: 8 Saith the Lord God who gathers the dispersed of Israel: Yet I will gather others to him, beside those of him that are gathered. John 1:45-46 Philip found Nathanael and said to him, ‘We have found him about whom Moses in the law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus son of Joseph from Nazareth.’ Nathanael said to him, ‘Can anything good come out of Nazareth?’ Philip said to him, ‘Come and see.’ Luke 4:24 Then [Jesus] said, ‘Truly I tell you, no prophet is accepted in the prophet’s hometown.’ Breakfast at the hotel. Begin the day with a special program in conjunction with the Beit HaGefen community center, which hosts the yearly Holiday of Holidays, a Muslim-Christian-Jewish celebration, including an intercultural walk through the Wadi Nisnas area of Haifa. Continue to the multi-faith city of Acre, for a guided visit through the ancient and contemporary towns, exploring the mosaic of Abrahamic faiths and their juxtaposition with the old and new, including the Underground Crusader city. -

INTERNATIONAL WATERS of the MIDDLE EAST from EUPHRATES-TIGRIS to NILE

'p MIN INTERNATIONAL WATERS of the MIDDLE EAST FROM EUPHRATES-TIGRIS TO NILE WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERtES 2 International Waters of the Middle East From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile Water Resources Management Series I. Water for Sustainable Development in the Twenty-first Century edited by ASIT K. BIswAs, MOHAMMED JELLALI AND GLENN STOUT International Waters of the Middle East: From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile edited by ASIT K. BlswAs Management and Development of Major Rivers edited by ALY M. SHADY, MOHAMED EL-MOTTASSEM, ESSAM ALY ABDEL-HAFIZ AND AsIT K. BIswAs WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES : 2 International Waters of the Middle East From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile Edited b' ASIT K. BISWAS Sponsored by United Nations University International Water Resources Association With the support of Sasakawa Peace Foundation United Nations Entne4rogramme' '4RY 1' Am ir THE SASAKAWA PEACE FOUNDATION OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS BOMBAY DELHi CALCUTTA MADRAS 1994 Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP Oxford New York Toronto Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi KualaLumpur Singapore Hong Kong Tokyo Nairobi Dar esSalaam Cape Town Melbourne Auckland Madrid anji.ssocia:es in Berlin Ibadan First published 1994 © United Nations University, International Water Resources Association, Sasakawa Peace Foundation and United Nations Environ,nent Programme, 1994 ISBN 0 19 563557 4 Printed in India Typeset by Alliance Phototypesetters, Pondicherry 605 013 Printed at Rajkamal Electric Press, Delhi 110 033 Published by Neil O'Brien, Oxford University Press YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110 001 This hook is dedicated to DR TAKASHI SHIRASU as a mark of esteem for his contributions to peace and a token of true regard for a friend Contents List of Contributors IX Series Preface xi Preface Xiii I. -

Israel a History

Index Compiled by the author Aaron: objects, 294 near, 45; an accidental death near, Aaronsohn family: spies, 33 209; a villager from, killed by a suicide Aaronsohn, Aaron: 33-4, 37 bomb, 614 Aaronsohn, Sarah: 33 Abu Jihad: assassinated, 528 Abadiah (Gulf of Suez): and the Abu Nidal: heads a 'Liberation October War, 458 Movement', 503 Abandoned Areas Ordinance (948): Abu Rudeis (Sinai): bombed, 441; 256 evacuated by Israel, 468 Abasan (Arab village): attacked, 244 Abu Zaid, Raid: killed, 632 Abbas, Doa: killed by a Hizballah Academy of the Hebrew Language: rocket, 641 established, 299-300 Abbas Mahmoud: becomes Palestinian Accra (Ghana): 332 Prime Minister (2003), 627; launches Acre: 3,80, 126, 172, 199, 205, 266, 344, Road Map, 628; succeeds Arafat 345; rocket deaths in (2006), 641 (2004), 630; meets Sharon, 632; Acre Prison: executions in, 143, 148 challenges Hamas, 638, 639; outlaws Adam Institute: 604 Hamas armed Executive Force, 644; Adamit: founded, 331-2 dissolves Hamas-led government, 647; Adan, Major-General Avraham: and the meets repeatedly with Olmert, 647, October War, 437 648,649,653; at Annapolis, 654; to Adar, Zvi: teaches, 91 continue to meet Olmert, 655 Adas, Shafiq: hanged, 225 Abdul Hamid, Sultan (of Turkey): Herzl Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Jewish contacts, 10; his sovereignty to receive emigrants gather in, 537 'absolute respect', 17; Herzl appeals Aden: 154, 260 to, 20 Adenauer, Konrad: and reparations from Abdul Huda, Tawfiq: negotiates, 253 Abdullah, Emir: 52,87, 149-50, 172, Germany, 279-80, 283-4; and German 178-80,230, -

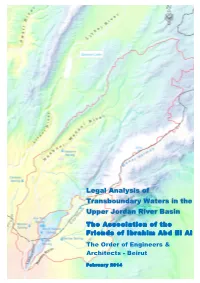

Legal Analysis of Transboundary Waters in the Upper Jordan River Basin

Legal Analysis of Transboundary Waters in the Upper Jordan River Basin The Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd El Al The Order of Engineers & Architects - Beirut February 2014 THE ASSOCIATION OF THE FRIENDS OF IBRAHIM ABD EL AL ( AFIAL) SPONSORED BY: THE ORDER OF ENGINEERS AND ARCHITECTS - BEIRUT Written by HE. Ziyad Baroud, Esq. Attorney at law, Managing Partner HBD-T Law firm, Lecturer at USJ, Former Lebanese Minister of Interior and Municipalities Me. Ghadir El-Alayli, Esq. Attorney at law, Senior Associate HBD-T, PhD student Chadi Abdallah, PhD Geosiences, Remote Sensing & GIS MarK Zeitoun, PhD Coordinator Reviewed Antoine Salameh, Eng. President, Scientific Committee of AFIAL by Prof Stephen McCaffrey McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific Michael Talhami, Eng. Independent researcher TO CITE THIS STUDY AFIAL, 2014. Legal Analysis of Transboundary Waters in the Upper Jordan River Basin. Beirut, Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd El Al. 91pp + Annexes NOTES This study was undertaken by a team assembled by the Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd el Al, with the generous support of the Order of Engineers and Architects of Lebanon. Any questions or comments about the study should be directed to AFIAL. AFIAL would like to emphasize that the analysis and recommendations are suggested without any prejudice to the state of relations between the Government of Lebanon and the Occupying State of Israel, and the non-recognition of the latter by the Government of Lebanon. Copyright © 2014, Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd el Al. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS III FIGURES VII TABLES IX ACRONYMS X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XI SECTION 1 – INTRODUCTION 1 1. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

Lost Opportunities for Peace in the Arab- Israeli Conºict

Lost Opportunities for Jerome Slater Peace in the Arab- Israeli Conºict Israel and Syria, 1948–2001 Until the year 2000, during which both the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Syrian negotiating pro- cesses collapsed, it appeared that the overall Arab-Israeli conºict was ªnally going to be settled, thus bringing to a peaceful resolution one of the most en- during and dangerous regional conºicts in recent history.The Israeli-Egyptian conºict had concluded with the signing of the 1979 Camp David peace treaty, the Israeli-Jordanian conºict had formally ended in 1994 (though there had been a de facto peace between those two countries since the end of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war), and both the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Syrian conºicts seemedLost Opportunities for Peace on the verge of settlement. Yet by the end of 2000, both sets of negotiations had collapsed, leading to the second Palestinian intifada (uprising), the election of Ariel Sharon as Israel’s prime minister in February 2001, and mounting Israeli-Palestinian violence in 2001 and 2002.What went wrong? Much attention has been focused on the lost 1 opportunity for an Israeli-Palestinian settlement, but surprisingly little atten- tion has been paid to the collapse of the Israeli-Syrian peace process.In fact, the Israeli-Syrian negotiations came much closer to producing a comprehen- Jerome Slater is University Research Scholar at the State University of New York at Buffalo.Since serving as a Fulbright scholar in Israel in 1989, he has written widely on the Arab-Israeli conºict for professional journals such as the Jerusalem Journal of International Relations and Political Science Quarterly. -

The Occupied Syrian Golan Alternative Tourism

THE OCCUPIED SYRIAN GOLAN ALTERNATIVE TOURISM MAJDAL SHAMS VALLEY OF TEARS CEASEFIRE LINE MOUNT HARMOON APPLE AND CHERRY ORCHARDS LAKE RAM DESTROYED SYRIAN VILLAGES QUNEITRA MOUNT TAL ABO EL NADA HIKING LOCAL SYRIAN FOOD AlMarsad The Arab Centre for Human Rights in the Golan Heights provides alternative tours challenging the Israeli narrative of the occupied Syrian Golan. We offer an alternative account of the history of the region and show the beauty of the Golan through a human rights lens. Our tours contribute to the local Syrian economy and give the local Syrian population the opportunity to discuss with visitors the reality of life under occupation. We provide different types of tours, according to your availability, interest and budget. Background The area known as the Syrian Golan or Golan Heights is a mountainous plateau in southwest Syria. During the 1967 Arab Israeli War, Israel militarily occupied over twothirds of the Syrian Golan. Today, this area is known as the occupied Syrian Golan / Golan Heights. Following the Israeli occupation, approximately 130,000 native Syrian inhabitants were forcibly transferred or displaced from their homes. Only five percent of the original population was able to remain. Subsequently, the Israeli military began a widespread campaign to demolish Syrian homes, destroying one city and 340 villages and farms. These were replaced by Israeli settlements, often built with stones from the destroyed villages and farms. Syrian names of the majority of geographic, cultural and historic sites were also altered or replaced as part of a process of ‘Israelization’ of the Golan. Today, there are 23.000 Israeli settlers in the Golan, living in 34 illegal settlements.