Квантна Музика Quantum Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Theory Cannot Consistently Describe the Use of Itself

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05739-8 OPEN Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself Daniela Frauchiger1 & Renato Renner1 Quantum theory provides an extremely accurate description of fundamental processes in physics. It thus seems likely that the theory is applicable beyond the, mostly microscopic, domain in which it has been tested experimentally. Here, we propose a Gedankenexperiment 1234567890():,; to investigate the question whether quantum theory can, in principle, have universal validity. The idea is that, if the answer was yes, it must be possible to employ quantum theory to model complex systems that include agents who are themselves using quantum theory. Analysing the experiment under this presumption, we find that one agent, upon observing a particular measurement outcome, must conclude that another agent has predicted the opposite outcome with certainty. The agents’ conclusions, although all derived within quantum theory, are thus inconsistent. This indicates that quantum theory cannot be extrapolated to complex systems, at least not in a straightforward manner. 1 Institute for Theoretical Physics, ETH Zurich, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to R.R. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:3711 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05739-8 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05739-8 “ 1”〉 “ 1”〉 irect experimental tests of quantum theory are mostly Here, | z ¼À2 D and | z ¼þ2 D denote states of D depending restricted to microscopic domains. Nevertheless, quantum on the measurement outcome z shown by the devices within the D “ψ ”〉 “ψ ”〉 theory is commonly regarded as being (almost) uni- lab. -

Toward Quantum Simulation with Rydberg Atoms Thanh Long Nguyen

Study of dipole-dipole interaction between Rydberg atoms : toward quantum simulation with Rydberg atoms Thanh Long Nguyen To cite this version: Thanh Long Nguyen. Study of dipole-dipole interaction between Rydberg atoms : toward quantum simulation with Rydberg atoms. Physics [physics]. Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris VI, 2016. English. NNT : 2016PA066695. tel-01609840 HAL Id: tel-01609840 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01609840 Submitted on 4 Oct 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DÉPARTEMENT DE PHYSIQUE DE L’ÉCOLE NORMALE SUPÉRIEURE LABORATOIRE KASTLER BROSSEL THÈSE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Spécialité : PHYSIQUE QUANTIQUE Study of dipole-dipole interaction between Rydberg atoms Toward quantum simulation with Rydberg atoms présentée par Thanh Long NGUYEN pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Soutenue le 18/11/2016 devant le jury composé de : Dr. Michel BRUNE Directeur de thèse Dr. Thierry LAHAYE Rapporteur Pr. Shannon WHITLOCK Rapporteur Dr. Bruno LABURTHE-TOLRA Examinateur Pr. Jonathan HOME Examinateur Pr. Agnès MAITRE Examinateur To my parents and my brother To my wife and my daughter ii Acknowledgement “Voici mon secret. -

A Critic Looks at Qbism Guido Bacciagaluppi

A Critic Looks at QBism Guido Bacciagaluppi To cite this version: Guido Bacciagaluppi. A Critic Looks at QBism. 2013. halshs-00996289 HAL Id: halshs-00996289 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00996289 Preprint submitted on 26 May 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A Critic Looks at QBism Guido Bacciagaluppi∗ 30 April 2013 Abstract This chapter comments on that by Chris Fuchs on qBism. It presents some mild criticisms of this view, some based on the EPR and Wigner’s friend scenarios, and some based on the quantum theory of measurement. A few alternative suggestions for implementing a sub- jectivist interpretation of probability in quantum mechanics conclude the chapter. “M. Braque est un jeune homme fort audacieux. [...] Il m´eprise la forme, r´eduit tout, sites et figures et maisons, `ades sch´emas g´eom´etriques, `ades cubes. Ne le raillons point, puisqu’il est de bonne foi. Et attendons.”1 Thus commented the French art critic Louis Vauxcelles on Braque’s first one- man show in November 1908, thereby giving cubism its name. Substituting spheres and tetrahedra for cubes might be more appropriate if one wishes to apply the characterisation to qBism — the view of quantum mechanics and the quantum state developed by Chris Fuchs and co-workers (for a general reference see either the paper in this volume, or Fuchs (2010)). -

The Hydrogen Atom (Finite Difference Equation/Discrete Wave Vectors/Bohr-Rydberg Formula) FREDERICK T

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 5753-5755, August 1986 Chemistry Discrete wave mechanics: The hydrogen atom (finite difference equation/discrete wave vectors/Bohr-Rydberg formula) FREDERICK T. WALL Department of Chemistry, B-017, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 Contributed by Frederick T. Wall, March 31, 1986 ABSTRACT The quantum mechanical problem of the hy- its wave vector energy counterpart.* If V is small compared drogen atom is treated by use of a finite difference equation in to mc2, then V and l9 are substantially the same, but for large place of Schrodinger's differential equation. The exact solu- negative values of V, the two can be significantly different. tion leads to a wave vector energy expression that is readily The next question to be answered is how the potential en- converted to the Bohr-Rydberg formula. (The calculations ergy is introduced into the finite difference equation. In our here reported are limited to spherically symmetric states.) The problem, we shall write that wave vectors reduce to the familiar solutions of Schrodinger's equation as c -- w. The internal consistency and limiting be- O(r - A) - 2(X + V/mc2)4(r) + /(r + A) = 0, [2] havior provide support for the view that the equations em- ployed could well constitute an approach to a relativistic for- with mulation of wave mechanics. X = = (1 - 26/E)"2 [3] In an earlier paper (1), I set forth a simple difference equa- EI/E tion for the wave mechanical description of a free particle. This was accompanied by a postulatory basis for interpreting where & is the wave vector energy, and certain parameters related to the energy, thus appearing to provide a possible connection to relativity. -

Note to 8.13 Students

Note to 8.13 students: Feel free to look at this paper for some suggestions about the lab, but please reference/acknowledge me as if you had read my report or spoken to me in person. Also note that this is only one way to do the lab and data analysis, and there are nearly an infinite number of other things to do that would be better. I made some mistakes doing this lab. Here are a couple I found (and some more tips): Use a smaller step and get more precise data than what we had. Then fit • a curve, don’t just pick out a peak. The Hg calibration is actually something like a sin wave instead of a cubic. • Also don’t follow the old version of Melissionos word for word. They use an optical system with a prism oppose to a diffraction grating. We took data strategically so we could use unweighted fits • The mystery tube was actually N, whoops my bad. We later found a • drawer full of tubes and compared the colors. It was obviously N. Again whoops, it was our first experiment okay?! 1 Optical Spectroscopy Rachel Bowens-Rubin∗ MIT Department of Physics (Dated: July 12, 2010) The spectra of mercury, hydrogen, deuterium, sodium, and an unidentified mystery tube were measured using a monochromator to determine diffrent properties of their spectra. The spectrum of mercury was used to calibrate for error due to optics in the monochronomator. The measurements of the Balmer series lines were used to determine the Rydberg constants for hydrogen and deuterium, 7 7 1 7 7 1 Rh =1.0966 10 0.0002 10 m− and Rd=1.0970 10 0.0003 10 m− . -

Contemporary Physics Uncollapsing the Wavefunction by Undoing

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Riverside] On: 18 February 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918975371] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Physics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713394025 Uncollapsing the wavefunction by undoing quantum measurements Andrew N. Jordan a; Alexander N. Korotkov b a Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, USA b Department of Electrical Engineering, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA First published on: 12 February 2010 To cite this Article Jordan, Andrew N. and Korotkov, Alexander N.(2010) 'Uncollapsing the wavefunction by undoing quantum measurements', Contemporary Physics, 51: 2, 125 — 147, First published on: 12 February 2010 (iFirst) To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00107510903385292 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00107510903385292 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

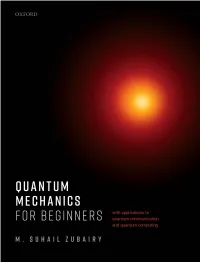

Quantum Mechanics for Beginners OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 10/3/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 10/3/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 10/3/2020, SPi Quantum Mechanics for Beginners OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 10/3/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 10/3/2020, SPi Quantum Mechanics for Beginners with applications to quantum communication and quantum computing M. Suhail Zubairy Texas A&M University 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 10/3/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © M. Suhail Zubairy 2020 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2020 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing -

Reformulation of Quantum Mechanics and Strong Complementarity from Bayesian Inference Requirements

Reformulation of quantum mechanics and strong complementarity from Bayesian inference requirements William Heartspring Abstract: This paper provides an epistemic reformulation of quantum mechanics (QM) in terms of inference consistency requirements of objective Bayesianism, which include the principle of maximum entropy under physical constraints. Physical constraints themselves are understood in terms of consistency requirements. The by-product of this approach is that QM must additionally be understood as providing the theory of theories. Strong complementarity - that dierent observers may live in separate Hilbert spaces - follows as a consequence, which resolves the rewall paradox. Other clues pointing to this reformu- lation are analyzed. The reformulation, with the addition of novel transition probability arithmetic, resolves the measurement problem completely, thereby eliminating subjectivity of measurements from quantum mechanics. An illusion of collapse comes from Bayesian updates by observer's continuous outcome data. Dark matter and dark energy pop up directly as entropic tug-of-war in the reformulation. Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Epistemic nature of quantum mechanics2 2.1 Area law, quantum information and spacetime2 2.2 State vector from objective Bayesianism5 3 Consequences of the QM reformulation8 3.1 Basis, decoherence and causal diamond complementarity 12 4 Spacetime from entanglement 14 4.1 Locality: area equals mutual information 14 4.2 Story of Big Bang cosmology 14 5 Evidences toward the reformulation 14 5.1 Quantum redundancy 15 6 Transition probability arithmetic: resolving the measurement problem completely 16 7 Conclusion 17 1 Introduction Hamiltonian formalism and Schrödinger picture of quantum mechanics are assumed through- out the writing, with time t 2 R. Whenever the word entropy is mentioned without addi- tional qualication, it refers to von Neumann entropy. -

Quantum Mechanics

Quantum Mechanics Richard Fitzpatrick Professor of Physics The University of Texas at Austin Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Intendedaudience................................ 5 1.2 MajorSources .................................. 5 1.3 AimofCourse .................................. 6 1.4 OutlineofCourse ................................ 6 2 Probability Theory 7 2.1 Introduction ................................... 7 2.2 WhatisProbability?.............................. 7 2.3 CombiningProbabilities. ... 7 2.4 Mean,Variance,andStandardDeviation . ..... 9 2.5 ContinuousProbabilityDistributions. ........ 11 3 Wave-Particle Duality 13 3.1 Introduction ................................... 13 3.2 Wavefunctions.................................. 13 3.3 PlaneWaves ................................... 14 3.4 RepresentationofWavesviaComplexFunctions . ....... 15 3.5 ClassicalLightWaves ............................. 18 3.6 PhotoelectricEffect ............................. 19 3.7 QuantumTheoryofLight. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 3.8 ClassicalInterferenceofLightWaves . ...... 21 3.9 QuantumInterferenceofLight . 22 3.10 ClassicalParticles . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 3.11 QuantumParticles............................... 25 3.12 WavePackets .................................. 26 2 QUANTUM MECHANICS 3.13 EvolutionofWavePackets . 29 3.14 Heisenberg’sUncertaintyPrinciple . ........ 32 3.15 Schr¨odinger’sEquation . 35 3.16 CollapseoftheWaveFunction . 36 4 Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics 39 4.1 Introduction .................................. -

Scientific American

Take the Nature Publishing Group survey for the chance to win a MacBookFind out Air more Physics Scientific American (June 2013), 308, 46-51 Published online: 14 May 2013 | doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0613-46 Quantum Weirdness? It's All in Your Mind Hans Christian von Baeyer A new version of quantum theory sweeps away the bizarre paradoxes of the microscopic world. The cost? Quantum information exists only in your imagination CREDIT: Caleb Charland In Brief Quantum mechanics is an incredibly successful theory but one full of strange paradoxes. A recently developed model called Quantum Bayesianism (or QBism) combines quantum theory with probability theory in an effort to eliminate the paradoxes or put them in a less troubling form. QBism reimagines the entity at the heart of quantum paradoxes—the wave function. Scientists use wave functions to calculate the probability that a particle will have a certain property, such as being in one place and not another. But paradoxes arise when physicists assume that a wave function is real. QBism maintains that the wave function is solely a mathematical tool that an observer uses to assign his or her personal belief that a quantum system will have a specific property. In this conception, the wave function does not exist in the world—rather it merely reflects an individual's subjective mental state. ADDITIONAL IMAGES AND ILLUSTRATIONS [QUANTUM PHILOSOPHY] Four Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics [THOUGHT EXPERIMENT] The Fix for Quantum Absurdity Flawlessly accounting for the behavior of matter on scales from the subatomic to the astronomical, quantum mechanics is the most successful theory in all the physical sciences. -

Quantum Physics (UCSD Physics 130)

Quantum Physics (UCSD Physics 130) April 2, 2003 2 Contents 1 Course Summary 17 1.1 Problems with Classical Physics . .... 17 1.2 ThoughtExperimentsonDiffraction . ..... 17 1.3 Probability Amplitudes . 17 1.4 WavePacketsandUncertainty . ..... 18 1.5 Operators........................................ .. 19 1.6 ExpectationValues .................................. .. 19 1.7 Commutators ...................................... 20 1.8 TheSchr¨odingerEquation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 20 1.9 Eigenfunctions, Eigenvalues and Vector Spaces . ......... 20 1.10 AParticleinaBox .................................... 22 1.11 Piecewise Constant Potentials in One Dimension . ...... 22 1.12 The Harmonic Oscillator in One Dimension . ... 24 1.13 Delta Function Potentials in One Dimension . .... 24 1.14 Harmonic Oscillator Solution with Operators . ...... 25 1.15 MoreFunwithOperators. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 26 1.16 Two Particles in 3 Dimensions . .. 27 1.17 IdenticalParticles ................................. .... 28 1.18 Some 3D Problems Separable in Cartesian Coordinates . ........ 28 1.19 AngularMomentum.................................. .. 29 1.20 Solutions to the Radial Equation for Constant Potentials . .......... 30 1.21 Hydrogen........................................ .. 30 1.22 Solution of the 3D HO Problem in Spherical Coordinates . ....... 31 1.23 Matrix Representation of Operators and States . ........... 31 1.24 A Study of ℓ =1OperatorsandEigenfunctions . 32 1.25 Spin1/2andother2StateSystems . ...... 33 1.26 Quantum -

Quantum Weirdness? It’S All in Your Mind

PHYSICS QUANTUM WEIRDNESS? IT’S ALL IN YOUR MIND A new version of quantum theory sweeps away the bizarre paradoxes of the microscopic world. The cost? Quantum information exists only in your imagination By Hans Christian von Baeyer lawlessly accounting for the behavior of matter on scales from the subatomic to the astronomical, quantum mechanics is the most successful theory in all the physical sciences. It is also the weirdest. In the quantum realm, particles seem to be in two places at once, information appears to travel faster than the speed of light, and cats can be dead and alive at the same time. Physicists have Fgrappled with the quantum world’s apparent paradoxes for nine decades, with little to show for their struggles. Unlike evolution and cosmology, whose truths have been incorporated into the gen eral intellectual landscape, quantum theory is still considered (even by many physicists) to be a bizarre anomaly, a powerful reci pe book for building gadgets but good for little else. The deep con fusion about the meaning of quantum theory will continue to add 46 Scientific American, June 2013 Photograph by Caleb Charland June 2013, ScientificAmerican.com 47 fuel to the perception that the deep things it is so urgently try hammer is also in a superposition, as is the THOUGHT EXPERIMENT Hans Christian von Baeyer is a theoretical particle ing to tell us about our world are irrelevant to everyday life and physicist and Chancellor Professor emeritus at the College vial of poison. And most grotesquely, the too weird to matter. of William and Mary, where he taught for 38 years.