Factors Associated with HIV Positive Sero-Status Among Exposed Infants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 / 38 Presidential Elections, 2016

Tuesday, February 23, 2016 15:38:16 PM Received Station: 27881/28010 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, 2016 (Presidential Elections Act, 2005, Section 48) RESULTS TALLY SHEET DISTRICT: 015 KASESE CONSTITUENCY: 077 BUKONZO COUNTY EAST Parish Station Reg. ABED AMAMA BARYAMUREEB BENON BUTA KIZZA MABIRIZI MAUREEN YOWERI Valid Invalid Total Voters BWANIKA MBABAZI A VENANSIUS BIRAARO BESIGYE JOSEPH FAITH KYALYA KAGUTA Votes Votes Votes KIFEFE WALUUBE MUSEVENI Sub-county: 001 KISINGA 001 KAGANDO 01 KAGANDO II LCI OFFICE (A-L) 504 2 1 3 0 263 0 0 78 347 18 365 0.58% 0.29% 0.86% 0.00% 75.79% 0.00% 0.00% 22.48% 4.93% 72.42% 02 KAGANDO PARISH HQRS (A-L) 460 4 3 0 1 222 2 1 95 328 13 341 1.22% 0.91% 0.00% 0.30% 67.68% 0.61% 0.30% 28.96% 3.81% 74.13% 03 KAGANDO II LCI OFFICE (M -Z) 480 1 0 1 0 235 2 0 70 309 28 337 0.32% 0.00% 0.32% 0.00% 76.05% 0.65% 0.00% 22.65% 8.31% 70.21% 04 KIBURARA BAPTIST CHURCH 460 4 4 3 0 224 3 1 87 326 12 338 1.23% 1.23% 0.92% 0.00% 68.71% 0.92% 0.31% 26.69% 3.55% 73.48% 05 KIBURARA PR. SCH.[A-L] 606 1 3 0 0 285 1 0 87 377 54 431 0.27% 0.80% 0.00% 0.00% 75.60% 0.27% 0.00% 23.08% 12.53% 71.12% 06 KISANGA LCI OFFICE 279 5 1 0 1 111 0 0 67 185 10 195 2.70% 0.54% 0.00% 0.54% 60.00% 0.00% 0.00% 36.22% 5.13% 69.89% 07 NYAMUGASANI PARISH 776 3 2 4 0 428 0 2 112 551 17 568 HQRS. -

Fight Against COVID-19

COMMUNITY NEWS Thursday, May 7, 2020 NV31 National COVID-19 fund gets more donations Former Lango Foundation PHOTO BY ABOU KISIGE prime minister sues boss CENTRAL NORTH By Nelson Kiva The Lango paramount chief, Yosam Ebii A day after the National Response Odur, has been dragged to court by to COVID-19 Fund made a his former prime minister, Dr Richard fresh appeal for support, several Nam, challenging him for appointing individuals and corporate Eng. James Ajal as the new premier. organisations flocked the Office Nam filed the notice to sue the of the Prime Minister (OPM) in Lango Cultural Foundation over Kampala to donate cash and non- irregularities in his dismissal from cash items. the position of prime minister by the “We remain committed to paramount chief. accord any necessary assistance Through his lawyer, Emmanuwel to fellow Ugandans and towards Egaru, Nam claims he was dismissed Government’s efforts to combat from office without following legal the coronavirus pandemic,” procedures. He argues that Chapter Sharon Kalakiire remarked while (4), Article 5 of the Lango Cultural handing over a consignment of Foundation constitution state that the items donated by SBC Uganda prime minister can only be dismissed if Limited to the Minister of General he is implicated in abuse of office or if Duties, Mary Karooro Okurut. he is mentally incapacitated. Karooro, who is also the political Minister Karooro Okurut (right) receiving relief items from employees of SBC Uganda advisor to the COVID-19 Fund, was accompanied by Dorothy Kisaka, the fund’s secretary and on Sunday indicated that they had chairperson of the fund, said. -

Kilembe Hospital to Re-Open Today Rumours on ADF Lt

WESTERN NEWS NEW VISION, Tuesday, June 4, 2013 9 UPDF dismisses Kilembe Hospital to re-open today rumours on ADF Lt. Ninsima Rwemijuma, the By JOHN THAWITE He disclosed that the 84 nurses are homeless after the untreated water from Uganda People’s Defence hospital would start by offering their houses were washed the Kasese Cobalt Company Forces second divison Kilembe Mines Hospital in services such as anti-retroviral Faulty away by the floods. factory. We have to purify spokesperson, has warned Kasese district re-opens its therapy, eye treatment, dental He requested for cement, it before using and it is not politicians in the Rwenzori gates to out-patients today, care, orthopaedics and timber and paint to be used enough for a big patient region against spreading after a month’s closure. immunisation. Dr. Edward Wefula, in repairing the hospital’s population,” Wefula added. rumours that Allied Democratic The facility was closed after Wefula said the 200-bed the superintendent of infrastructure. The hospital is co-managed Forces(ADF) rebels have it was ravaged by floods that hospital was not yet ready for Kilembe Mines Hospital, Wefula said the break down by Kilembe Mines, the Catholic crossed into Uganda. He said hit the area on May 1. in-patient admissions and said the sewerage system in the facility’s sewerage Church and the health such people want to disrupt “The out-patient department major surgical operations in the facility was down system had resulted in the ministry. peace. Ninsiima said according is ready to resume services. because most of the essential contamination of water. -

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

Highlights of the Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness in Uganda

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE PREPAREDNESS IN UGANDA 21st MAY 2019 (12:00 HRS) – UPDATE NO 118 SITUATION UPDATE FROM DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO FOR 20th MAY 2019 WITH DATA UP TO 19th MAY 2019 Cumulative cases: 1,826 Confirmed cases: 1,738 Probable: 88 Total deaths: 1,218 a) EVD SITUATIONAL UPDATE IN UGANDA There is NO confirmed EVD case in Uganda. Active case search continues in all communities, health facilities and on formal and informal border crossing in all districts especially in the high-risk ones. Alert cases continue to be picked, isolated, treated and blood samples picked for testing by the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI). The alerts are highlighted in the specific district reports below under the Surveillance section. b) PREPAREDNESS IN THE FIELD (PROGRESS AND GAPS) COORDINATION SURVEILLANCE ACTIVITIES Kasese District Achievements Two (2) suspected cases from Kyaka II Camp were detected, samples were picked and taken to Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) for testing. 32 school zonal leaders were trained on chlorine preparation at the district headquarters. Gaps and Challenges 1 There is lack of EVD logistics such as gloves, infrared thermometers, batteries, triple packing etc. Ntoroko District Achievements Support supervision was conducted at PoEs in the district. Surveillance team visited Stella Maris HCIII and MTI facilities where they updated staff and volunteers on EVD. Number of people screened at PoEs in Ntoroko District on 20th May 2019. No PoE site No of persons screened 1 Kigungu 34 2 Ntoroko Main 67 3 Fridge 0 4 Transami 153 5 Kanara 0 6 Rwagara 258 7 Katanga 56 8 Kamuga 99 9 Katolingo 24 10 Mulango 43 11 Rwentuhi 65 12 Haibale South 57 13 Kabimbiri 0 14 Kyapa 53 15 Kayanja I 31 16 Kayanja II 69 17 Budiba 0 2 Total 1,009 Gaps and Challenges Some PoEs have no tents. -

Ebola Virus Disease in Uganda

EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE IN UGANDA Situation Report 15 Jun 2019 SitRep #04 Deaths 03 Cases 1. Situation update 03 Key Highlights 03 cumulative cases (00 probable 03 confirmed) All (03) confirmed cases have died (CFR =100%) There are 96 contacts under follow up o None has developed symptoms to date Active case search and death surveillance are ongoing in the health facilities and the communities as the district response team continue to investigate all alerts The burial of the Queen Mother tomorrow has been moved to Bundibugyo. Several interventions have been put in place; hand washing facilities, screening of all people attending the burial, securing of all entrances, footbaths set up and education of the masses about EVD Background On 11th June 2019, the Ministry of Health of Uganda declared the 6th outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in the country affecting Kasese district in South Western Uganda. The first case was a five-year-old child with a recent history of travel to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This child was one of 6 people that travelled from the DRC while still being monitored as suspect cases following a burial of the grandfather who succumbed to EVD. The child was ill by the time he crossed into Uganda and the mother took him for medical care at Kagando hospital in Kasese district with symptoms of vomiting blood, bloody diarrhea, muscle pain, headache, fatigue and abdominal pain. The child tested positive for Ebola Zaire by 1 PCR and he later died on 11th June 2019. Two other members of the family, a grandmother and 3-year-old brother also tested positive for Ebola on 12 June 2019 and the grandmother died later the same day. -

2017 Statistical Abstract – Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF ENERGY AND MINERAL DEVELOPMENT 2017 STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2017 Statistical Abstract – Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development i FOREWORD The Energy and Mineral Development Statistics Abstract 2017 is the eighth of its kind to be produced by the Ministry. It consolidates all the Ministry’s statistical data produced during the calendar year 2017 and also contains data dating five years back for comparison purposes. The data produced in this Abstract provides progress of the Ministry’s contribution towards the attainment of the commitments in the National Development Plan II and the Ministry’s Sector Development Plan FY2015/16 – 2019/20. The Ministry’s Statistical Abstract is a vital document for dissemination of statistics on Energy, Minerals and Petroleum from all key sector players. It provides a vital source of evidence to inform policy formulation and further strengthens and ensures the impartiality, credibility of data/information collected. The Ministry is grateful to all its stakeholders most especially the data producers for their continued support and active participation in the compilation of this Abstract. I wish also to thank the Energy and Mineral Development Statistics Committee for the dedicated effort in compilation of this document. The Ministry welcomes any contributions and suggestions aimed at improving the quality of the subsequent versions of this publication. I therefore encourage you to access copies of this Abstract from the Ministry’s Head Office at Amber House or visit the Ministry’s website: www. energyandminerals.go.ug. Robert Kasande PERMANENT SECRETARY 2017 Statistical Abstract – Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development ii TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................... -

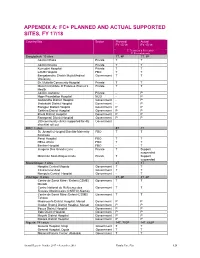

Appendix A: Fc+ Planned and Actual Supported Sites, Fy 17/18

APPENDIX A: FC+ PLANNED AND ACTUAL SUPPORTED SITES, FY 17/18 Country/Site Sector Planned Actual FY 17/18 FY 17/18 T: Treatment & Prevention P: Prevention-only Bangladesh: 15 sites 7T, 4P 7T, 8P Ad-Din Dhaka Private T T Ad-Din Khulna Private T T Kumudini Hospital Private T T LAMB Hospital FBO T T Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical Government T T University Dr. Muttalib Community Hospital Private T T Mamm's Institute of Fistula & Women's Private T T Health Ad-Din Jashohor Private - P Hope Foundation Hospital NGO - P Gaibandha District Hospital Government - P Jhalakathi District Hospital Government - P Rangpur District Hospital Government P P Satkhira District Hospital Government P P Bhola District Hospital Government P P Ranagmati District Hospital Government P P 200 community clinics supported for 4Q Government checklist roll out DRC: 4 sites 5T 4T St. Joseph’s Hospital/Satellite Maternity FBO T T Kinshasa Panzi Hospital FBO T T HEAL Africa FBO T T Beniker Hospital FBO - T Imagerie Des Grands-Lacs Private T Support suspended Maternité Sans Risque Kindu Private T Support suspended Mozambique: 3 sites 2T 3T Hospital Central Maputo Government T T Clinica Cruz Azul Government T T Nampula Central Hospital Government - T WA/Niger: 9 sites 3T, 6P 3T, 6P Centre de Santé Mère / Enfant (CSME) Government T T Maradi Centre National de Référence des Government T T Fistules Obstétricales (CNRFO),Niamey Centre de Santé Mère /Enfant (CSME) Government T T Tahoua Madarounfa District Hospital, Maradi Government P P Guidan Roumji District Hospital, Maradi Government -

MAUL Bulletin, We Share with You a Detailed

MAUL July 2020 BULLETIN Volume 3 Issue 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Hello, • Support to National Response and Relief Ef- forts in Combating COVID-19 Enhancing human health involves the use of innovative ap- • Emergency Delivery of Medicines to Kilembe proaches and best practices to procure and deliver medi- Mines Hospital Amid Flash Floods cines and health commodities to patients when and where • Logistics Team in Action During the COVID- they need them the most. However, with the emergence of 19 Pandemic the COVID-19 pandemic, we have had to find new and in- • Procurement Agency: Mitigating Sourcing Risk During COVID-19 novative ways to ensure an uninterrupted supply of medi- • CDC & Implementing Partner Communica- cines to over 240,000 people. We implemented a business tors’ Meeting continuity plan that aimed at keeping staff safe while ensur- • Working From Home: Joseph’s Experience ing continuity of procurement, supply chain and health sys- • COVID-19 Pandemic: Our Response & Inno- tems strengthening operations to avert treatment interrup- vation tions for the people that need the medicines the most. • COVID-19 Training: Infection Prevention and Use of Virtual Working Applications Through the MAUL bulletin, we share with you a detailed insight into how we have been able to continue our opera- EDITORIAL TEAM tions running sustainably, keeping our staff and the wider • Arthur Muwanga community safe while delivering on our commitment of en- • Sheba Nakimera suring access to life-saving medicines to all that need them. • Josephine Tamale • EmmaLinda Nassali Cheers! 1 SUPPORT TO THE NATIONAL RESPONSE & RELIEF EFFORTS IN COMBATING COVID-19 Medical Access Uganda Limited (MAUL) donated managing the current COVID-19 crisis. -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3 -

Further Observations on the Relationship Between Serum Mitochondrial Aspartate Transaminase and Parasitic Infection

FURTHER OBSERVATIONS ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SERUM MITOCHONDRIAL ASPARTATE TRANSAMINASE AND PARASITIC INFECTION. UNEXPECTED ABSENCE OF HUMAN SCHISTOSOMIASIS AROUND LAKES GEORGE AND EDWARD (UGANDA) T.R.C. Boyde Biochemistry Department, University of Hong Kong. ~d J.D. Gatenby Davies, Nairobi Laboratories, Nairobi, Kenya. ABSTRACT 1) Contrary to prediction, no cases of schistosomiasis could be detected in two lakeside communities. 2) Serum levels of mitochondrial aspart'ate tr~saminase (mAAT) in these communities were apparently unrelated to the presence or ,absence of detectable malaria parasites .. 3) By contrast, serum mAAT was significantly raised in 3 'healthy' cases of schistosomiasis who were otherwise comparable with the lakeside dwellers. (Significance was reached notwithstanding the paucity of cases). 4) These observations should be extended especially in respect of the Asian region where different species of Schistosoma are i~volved in para• sitisation, but progress has been blocked by lack of finance. INfRODUCTION Ongom and Bradley (1) studied a community living beside the Nile at Panyagoro, West Nile (Uganda) and found ~ extremely high level of infection with Schistosoma m~soni. They suggested that communities living in similar conditions elsewhere, including specifically t~~ area of the study reported here, would be found to have similar para?ite loads. The Hippopotamus population of Lakes George and Edward is infected with parasites of the same genus (2,3) ~d carrier snails of an appropriate species are present (4). Nevertheless, m~y Uganda residents believed that these lakes were safe and it therefore seemed worth determining what the prevalence really was, for reasons both of scientific and local public health interest. -

Kasese Town Council

KASESE TOWN COUNCIL Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Waste Composting Plant and Landfill for Kasese Town Council Prepar ed By: Enviro-Impact and Management Consults ST Public Disclosure Authorized Total Deluxe House, 1 Floor, Plot 29/33, Jinja Road P.O. Box 70360 Kampala, Tel: 41-345964, 31-263096, Fax: 41-341543 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.enviro-impact.co.ug February 2007 Kasese Town Council PREPARERS OF THIS REPORT ENVIRO-IMPACT and MANAGEMENT CONSULTS was contracted by Kasese Town Council to undertake the Environmental impact Assessment study of the proposed Waste Composting Plant and Landfill, and prepare this EIS on their behalf. Below is the description of the lead consultants who undertook the study. Aryagaruka Martin BSc, MSc (Natural Resource Management) Team Leader ………………….. Otim Moses BSc, MSc (Industrial Chemistry/Environmental Systems Analysis and Management) …………………… Wilbroad Kukundakwe BSc Industrial Chemistry …………………… EIS Kasese Waste Site i EIMCO Environmental Consultants Kasese Town Council TABLE OF CONTENTS PREPARERS OF THIS REPORT ........................................................................................................I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................................................. V ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................................... V EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...............................................................................................................VI