Neither Grobalized Nor Glocalized: Fuguet’S Or Lemebel’S Metropolis?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan's Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32d241sf Author Perelman, Elisheva Avital Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Professor John Lesch Professor Alan Tansman Fall 2011 © Copyright by Elisheva Avital Perelman 2011 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Tuberculosis existed in Japan long before the arrival of the first medical missionaries, and it would survive them all. Still, the epidemic during the period from 1890 until the 1920s proved salient because of the questions it answered. This dissertation analyzes how, through the actions of the government, scientists, foreign evangelical leaders, and the tubercular themselves, a nation defined itself and its obligations to its subjects, and how foreign evangelical organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association (the Y.M.C.A.) and The Salvation Army, sought to utilize, as much as to assist, those in their care. -

Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB issue 27: November -December 2001 FILM FESTIVAL OF CATALUNYA AT SITGES Fresh from Japan: Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin The International Film Festival of Catalunya (October 4 - 13) held at Sitges - the charming seaside village just south of Barcelona, infused with life from the international gay community - this year again presented a mix of mainstream and fantastic film. (The festival's original title was Festival of Fantastic Cinema.) The more mainstream section (called Gran Angular ) showed 12 films only as opposed to the large offering of 27 films in the Fantastic section, evidence that this genre still predominates even though it is no longer exclusive. Japan made a big showing this year in both categories. Two feature-length animated films caught the attention of Sara Martin , an English literature teacher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and anime fan, who reports here on the latest offerings by two of Japan's most outstanding anime film makers, and gives us both a wee history and future glimpse of the anime genre - it's sure not kids' stuff and it's not always pretty. Japanese animated feature films are known as anime. This should not be confused with manga , the name given to the popular printed comics on which anime films are often based. Western spectators raised in a culture that identifies animation with cartoon films and TV series made predominately for children, may be surprised to learn that animation enjoys a far higher regard in Japan. -

Iat. "__F «**» -»¦*. «. Nm-Eal Season

" an entire The , But one fact need be added to complete the of the of tho press. npon the. législature to repeal tbe laws by cisco cierta municipal, ticket. MtJSlO AKD THE eu., &!)_§ ^venina. pected respectable portion ndi-m of the have are oonfident- of eaiTyirig the conspicuous novelty of this system of college DR__m]_ _Ämn»tintiüe, But we call attention to this last caite, as it1 '."which the ptO-MUt City Republio-M »nd "Th« Mar- "obtained and their power, and State, the lowest estimât« of their majority government The "court" in the Iowa .Col¬ THE COMIITO OPERA SEASOrT. IkwíilV TimATO-.-''Little Neu," «bows how eoniBO- has tooome the practice perpetuated to consists of five men and two Ifcieeta" Lett« tb« »bortioniitB. "to give to the City of New-York . form of being .,«900, and the highest 10,000. Owing lege young Ia T. "__f «**» -»¦*. «. nm-eal season he* Mia« Fanny ob* tho ürfernal art« of "** «¦* aa Pirra Avbíítj» TH«át«».--"I_>iTOtt».,' such as shall bo devised or the fact that there are no telegraph lines in young women, 5?__L. UKYotlt ._¦ P»~iP«*t« the vW Something mu»t be done to stop these wioked "government ap¬ aaaaaaaaaaaas it.H aT-11 ann Wirti«, bol* cot to a*. It would be t-t-Hfev*. Mr. »nd Mm. our wisest and best and i ii ai iv parU of the State, it m doubtful if wo Hi tl_ rMÙT. Oband Opera Hoübm.." Jasper." practloes ; and If onr prt»ent laws are insuf¬ proved by citixens, terpret pu_. -

Manga! Manga!: the World of Japanese Comics, 1998, Frederik L

Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics, 1998, Frederik L. Schodt, Kodansha International, 1998 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1HTCRzm http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=Manga%21+Manga%21%3A+The+World+of+Japanese+Comics DOWNLOAD http://wp.me/2Zqkv http://bit.ly/1oODmJz The Otaku Encyclopedia An Insider's Guide to the Subculture of Cool Japan, パトリック・ウィリアムガルバレス, Patrick W. Galbraith, Jun 25, 2009, Social Science, 248 pages. Otaku - Japan's anime nerds, game geeks and pop-idol fanboys - originates from a polite second-person pronoun meaning 'your home' in Japanese. This guide offers an insight into. Japanese Visual Culture , Mark W. MacWilliams, Jan 29, 2008, Art, 352 pages. Born of Japan's cultural encounter with Western entertainment media, manga (comic books or graphic novels) and anime (animated films) are two of the most universally recognized. Dreamland Japan Writings on Modern Manga, Frederik L. Schodt, 1996, Literary Collections, 360 pages. Discusses the different forms, styles, artists, and publishers of manga, the popular form of comic book in Japan.. Nextworld, Volume 1 , , 2003, Comics & Graphic Novels, 168 pages. World leaders start a political conflict over what to do with creatures who have acquired superior abilities as a result of nuclear testing.. Astro Boy Volume 3 , Osamu Tezuka, May 28, 2002, Comics & Graphic Novels, . A timeless comics and animation classic, Osamu Tezuka' Astro Boy is still going strong nearly half a century after its creation, and Dark Horse brings Tekuza's original Astro. Lost World, Volume 1 , , 2003, Juvenile Fiction, 246 pages. -

JPNS5003 Understanding Manga and Anime (Semester 2)

09/25/21 JPNS5003 Understanding Manga and Anime | Oxford Brookes Reading Lists JPNS5003 Understanding Manga and View Online Anime (Semester 2) 82 items Key texts: Weekly schedule (39 items) Week 1: An Introduction to Anime (2 items) The castle of Cagliostro - Hayao Miyazaki, Yuji Ohno, 2005 Audio-visual document The Castle of Cagliostro - Hayao Miyazaki, 2000 Audio-visual document Week 2: An Introduction to Manga (6 items) Dororo: Vol.1 - Osamu Tezuka, c2008 Book Dororo: Vol.2 - Osamu Tezuka, c2008 Book Dororo: Vol.3 - Osamu Tezuka, c2008 Book Osamu Tezuka's Metropolis - Taro ̄ Rin, Osamu Tezuka, Fritz Lang, 2009 Audio-visual document Osamu Tezuka's Metropolis - Osamu Tezuka, Fritz Lang, Taro ̄ Rin, 2003 Audio-visual document Metropolis - Osamu Tezuka, Taro ̄ Rin, Toshiyuki Honda, 2002 Audio-visual document Week 3: Manga for Boys and Girls (8 items) 1/7 09/25/21 JPNS5003 Understanding Manga and Anime | Oxford Brookes Reading Lists From Eroica with love: Vol.1 - Aoike Yasuko, Tony Ogasawara, 2004 Book From Eroica with love: Vol.2 - Aoike Yasuko, Tony Ogasawara, 2005 Book From Eroica with love: Vol.3 - Aoike Yasuko, Tony Ogasawara, 2005 Book Slam dunk: Vol. 1: Sakuragi - Takehiko Inoue, 2008 Book Slam dunk: Vol. 2: New power generation - Takehiko Inoue, 2009 Book Slam dunk: Vol. 3: The challenge of the common shot - Takehiko Inoue, 2009 Book Slam dunk: Vol. 4: Enter the hero!! - Takehiko Inoue, 2009 Book Revolutionary girl Utena: the movie - Kunihiko Ikuhara, Chiho Saito, 2000 Audio-visual document Week 4: Manga for Adults (5 items) Lone Wolf and Cub: Vol.1: The assassin's road - Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima, 2000 Book | Follow the link to access a scan of the chapter 'Son for hire, sword for hire' Lone Wolf and Cub: Vol.2: The gateless barrier - Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima, 2000 Book Lone Wolf and Cub: Vol.3: The flute of the fallen tiger - Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima, 2000 Book Lone Wolf and Cub: Vol.4: The bell warden - Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima, 2000 Book Salaryman Kintaro: Vols. -

LA-350 Control De Calidad Para Alimentos • Productos Farmacéuticos • Cosméticos

Analizador de distribución de tamaño de partículas por dispersión de Rayos Láser compacto y potente NUEVO LA- 350 Control de Calidad para Alimentos • Productos Farmacéuticos • Cosméticos Explorar el futuro Sistemas de pruebas para automotores | Procesos y Medio ambiente | Medicina | Semiconductores | Ciencia Analizador de tamaño de partículas compacto y potente El Analizador de Distribución de Tamaño de Partículas LA-350 de HORIBA es la combinación ideal de rendimiento, precio y tamaño. Basado en el avanzado diseño óptico de los analizadores de la serie LA anteriores, el analizador LA-350 brinda un equilibrio armonioso entre alta funcionalidad, fácil operación, bajo mantenimiento y rentabilidad. El diseño optimizado permite un banco óptico compacto, lo que da lugar a un uso eficiente del espacio en la mesada, conservando al mismo tiempo la exactitud, precisión y resolución por la que son famosos los analizadores de HORIBA. Potente, conveniente y de rendimiento excepcional para satisfacer sus necesidades. 操躍 Pequeño y potente La combinación de banco óptico y bomba de circulación en un solo sistema es uno de los diseños más populares de HORIBA. Ahora este diseño tiene un tamaño mucho más pequeño que permite mover el analizador de un lugar a otro. Esto es especialmente valioso para situaciones de control de calidad en las que los lugares de muestreo y análisis deben separarse para evitar la contaminación. Además, debido a que requiere menos espacio, es posible colocar el instrumento donde se lo necesite. Un sistema de circulación potente y versátil Un sistema óptico estable y confiable El banco óptico y la bomba de circulación se combinan en un El diseño óptico de HORIBA asegura exactitud y medición único sistema compacto. -

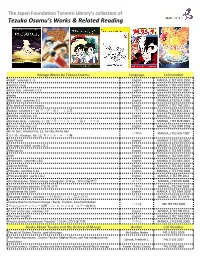

Tezuka Osamu Booklist

The Japan Foundation Toronto Library’s collection of Tezuka Osamu’s Works & Related Reading Manga Works by Tezuka Osamu Language Call number Adolf : volumes 1 - 5 English MANGA_E TEZ ADO 1995 Apollo's song English MANGA_E TEZ APO 2007 Astro boy : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ AST 2002 Ayako English MANGA_E TEZ AYA 2010 Black Jack : volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ BLA 2008 The book of human insects English MANGA_E TEZ THE 2011 Budda : volumes 1~14 ブッダ:第1-14巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUD 2011 Buddha : volumes 1-8 English MANGA_E TEZ BUD 2003 Burakku Jakku : volumes 1~22 ブラックジャック:第1-22巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUR 2004 Dororo : Volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ DOR 2008 Hi no tori : Hinotori No. 12, Girisha, Roma hen 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ HIN 1987 火の鳥 : Hinotori. No. 12, ギリシャ・ローマ編 Lost World English MANGA_E TEZ LOS 2003 Message to Adolf : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ MES 2012 Metropolis English MANGA_E TEZ MET 2003 MW English MANGA_E TEZ MW 2007 Nextworld : volumes 1 &2 English MANGA_E TEZ NEX 2003 Ode to Kirihito English MANGA_E TEZ ODE 2006 Phoenix : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ PHO 2003 Princess knight : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ PRI 2011 Shintakarajima : boken manga monogatari 新寳島 : 冒険漫画物語 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Shintakarajima tokuhon 新寶島 読本 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Swallowing the Earth English MANGA_E TEZ SWA 2009 Tetsuwan Atomu : volumes 1~17 鉄腕アトム:第 1-17 巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ TET 1979 Tezuka Osamu no Dizuni manga : Banbi, Pinokio : kara fukkokuban 日本語 REF TEZ TEZ 2005 手塚治虫のディズニー漫画 : バンビ, ピノキオ : カラー復刻版 Triton of the sea : volumes 1-2 English MANGA_E TEZ TRI 2013 The Twin Knights English MANGA_E TEZ TWI 2013 Tezuka Osamu kessakusen "kazoku"手塚治虫傑作選 家族 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ KAZ 2008 Books About Tezuka and the History of Manga Author Call Number The art of Osamu Tezuka : god of manga McCarthy, Helen 741.5 M32 2009 The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga/anime Schodt, Frederik L. -

Migration Governance Indicators Local

City of São Paulo | PROFILE 2019 LOCAL MIGRATION GOVERNANCE INDICATORS The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or the IOM Member States. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well‐being of migrants. While efforts have been taken to verify the accuracy of this information, neither The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. nor its affiliates can accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this information. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 P.O. Box 17 Switzerland Tel.: +41.22.717 91 11 Fax: +41.22.798 61 50 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.iom.int PUB2019/009/E With research and analysis by _______________ ISBN 9788594066077 © 2019 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _______________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Metropolismetr Integrated Power Amplifiers Series

METROPOLISMETR INTEGRATED POWER AMPLIFIERS SERIES E’ INDUBBIAMENTE UNICO E INIMITABILE. IL MITO DI TUTTI QUELLI CHE AMANO LA MUSICA. IS UNDOUBTEDLY A UNIQUE AND INIMITABLE. A REAL ICON FOR MUSIC LOVERS. NYC 100i Dual Mono Integrated Amplifier Power stage (1ch): 4 x KT66 Driver (1ch): 12BH7 MET Input stage (1ch): 12AX7-ECC83 Configuration: Parallel Push-Pull ult. Power output: 100W RMS into 4/8 ohm each channel AB1 class Frequency resp.: 20Hz to 20KHz +-0.5dB Input Impedance: 50Kohm ROP Input sensitivity: 200mV / 100W Signal/Noise ratio: >90dB, A weighted Inputs: 5 Line level inputs; DAC, Tuner, DVD, CDP, XLR. Pre output: Volume controlled NYC100i OLIS Power cons.: 500W Max Dim.: (w,d,h) 450x630x260mm Molti amanti della musica scelgo- Weight: 50.0 Kg no l’amplificatore Metropolis come spina dorsale del proprio sistema audio. Il motivo è sempli- NYC175i ce, questi amplificatori integrati producono un suono incredibil- NYC 175i mente naturale da qualsiasi Dual Mono Integrated Amplifier sorgente musicale. Power stage (1ch): 4 x KT88 NYC200i Many music lovers choose Driver (1ch): 12BH7 Synthesis Metropolis series Input stage (1ch): 12AX7-ECC83 Integrated Amplifier to be the Configuration: Parallel Push-Pull ult backbone of their audio system Power output: 180W RMS into 4/8 ohm or home stereo.The reason is each channel AB1 class Frequency resp.: 20Hz to 20KHz +-0.5dB simple, these Integrated ampli- Input Impedance: 50Kohm fiers produce an incredible Input sensitivity: 200mV / 180W natural sound from any music Signal/Noise ratio: >90dB, A weighted -

Informe De Actividades – Abril – Junio 2012

Activities Report: July 2013 – October 2013 Metropolis Activities Report July 2013–October 2013 1. METROPOLIS ANNUAL MEETING 1.1 Sessions of the Metropolis Annual Meeting in Johannesburg 2013 The 2013 Metropolis Annual Meeting, held in Johannesburg, closed to great success on 19 July 2013, having drawn over 400 participants from different cities from around the world. Over the four days of meetings, the ‘Caring Cities’ theme was present in all of the sessions held. Experts and political representatives acted as the spokespeople for their respective cities to make the meetings a discussion forum for the exchange of knowledge and to give the delegates present a first-hand account of their experiences. Over the course of the first day of sessions, the South African Cities Network panel discussion started, which analyzed the Ubuntu concept related to the meeting’s theme of Caring Cities. The panel analysis kicked off the rest of the meetings that addressed various sub-themes related to these concepts. Metropolis and UN-Habitat collaborated once again through the Safer Cities Global Network and presented the outcomes of a number of outstanding experiences carried out by different cities on the African continent and in Latin America which apply the “safe cities” concept. The thematic sessions, organized by the city of Johannesburg, were very well attended by the delegates. Over the six sessions, the Ubuntu philosophy linked with the Caring Cities slogan was present with the following themes: food resilience; agile cities; the informal economy; resilience of resources; committed citizens; and social cohesion. To celebrate International Nelson Mandela Day, the city of Johannesburg organized an activity by which the delegates spent 67 minutes of their time in an altruistic fashion, offering customized toys to the Entokozweni daycare center. -

Hearing the Cry in Black Diasporic and Latina/O Poetics

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 15 (2013) Issue 4 Article 7 Hearing the Cry in Black Diasporic and Latina/o Poetics Rachel E. Ellis Neyra Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ellis Neyra, Rachel E. -

Libels Statl's,METROPOLIS

B'rt OMAHA'S GREATEST Per Y_ $2.H AND BEST linf,JI. ~ Ie HE WEEKLY NEWSPAPER VOL. XX." OMAHA, NEBRASKA. FRIDAY SEPTEMBER 12th, 1924. No. 41, Big Money Being Paid At ace eet KU KlUXi KIM" Stm· BITTERLY BOYS ALL CASHING IN ON LONG liBELS STATl'S, METROPOLIS SHOTS AT AK·SAR·BEN FIELD Wheeler ami Ris "lteporters,r In -A. Desperate Ponies Are Not ~unning True To Form Which Effort To Win RecaD,Use. I{: K Organization Pleases Betters Who Like The Long Shots BUTLER kND1€lWFEY PUT OlIff 6F' LODGE SATURDAY RACES PROMISE SENSATIONS Click Of Fake Rdormers In ~lad Attempt To Get Into Office Followers Of Race Game Get Good Tips From Schilling, ClookeI' AssanltCity Under Guise Of Rapping Tom Dennison And Tad Evans-Some Bum Ones Out At The Track-Crowtls Grasp At Floating:Straws Like Drowning Rats- Getting Better-Many New Pony "Faces" This Season . '" Petitions Turned Down. Rank Ontsiders In The Aloney. Tom Dennison has been awarded about himself. The ~tory leaves The weather is warming up. So chickens one finds running about a. new title by Lyman Wheeler, offi- nothing unturned to libel oar city, is the enthusiasm for the Ak-Sar-Ben nowadays. She paid her backers cial representative in Omaha of the and the author of it all is no other races now on in full tilt out at the $14.60 while most feminine .fowl in Ku Klux Klan organ. \Tery ,. few, oi,than our dear Mr. Wheeler, who on famous Ak track. The long shot boys this neck of the woods wouldn't let these publications come' to Omaha top of it all has the unadulterated gall have been having a hellova good time you off for that amount much less which makes it possible for that organ to set hiUlSelf up as a model of what cashing in on their hunches so far turn it over to you.