Transient Gene Expression Following DNA Transfer to Plant Cells: the Phenomenon; Its Causes and Some Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Molecular Farming: a Viable Platform for Recombinant Biopharmaceutical Production

plants Review Plant Molecular Farming: A Viable Platform for Recombinant Biopharmaceutical Production Balamurugan Shanmugaraj 1,2, Christine Joy I. Bulaon 2 and Waranyoo Phoolcharoen 1,2,* 1 Research Unit for Plant-Produced Pharmaceuticals, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacognosy and Pharmaceutical Botany, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +66-2-218-8359; Fax: +66-2-218-8357 Received: 1 May 2020; Accepted: 30 June 2020; Published: 4 July 2020 Abstract: The demand for recombinant proteins in terms of quality, quantity, and diversity is increasing steadily, which is attracting global attention for the development of new recombinant protein production technologies and the engineering of conventional established expression systems based on bacteria or mammalian cell cultures. Since the advancements of plant genetic engineering in the 1980s, plants have been used for the production of economically valuable, biologically active non-native proteins or biopharmaceuticals, the concept termed as plant molecular farming (PMF). PMF is considered as a cost-effective technology that has grown and advanced tremendously over the past two decades. The development and improvement of the transient expression system has significantly reduced the protein production timeline and greatly improved the protein yield in plants. The major factors that drive the plant-based platform towards potential competitors for the conventional expression system are cost-effectiveness, scalability, flexibility, versatility, and robustness of the system. Many biopharmaceuticals including recombinant vaccine antigens, monoclonal antibodies, and other commercially viable proteins are produced in plants, some of which are in the pre-clinical and clinical pipeline. -

Therapeutic Recombinant Protein Production in Plants: Challenges and Opportunities

Received: 25 April 2019 | Revised: 23 July 2019 | Accepted: 20 August 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ppp3.10073 REVIEW Therapeutic recombinant protein production in plants: Challenges and opportunities Matthew J. B. Burnett1 | Angela C. Burnett2 1Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, New Haven, CT, USA Societal Impact Statement 2Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, Therapeutic protein production in plants is an area of great potential for increasing NY, USA and improving the production of proteins for the treatment or prevention of disease Correspondence in humans and other animals. There are a number of key benefits of this technique Angela C. Burnett, Brookhaven National for scientists and society, as well as regulatory challenges that need to be overcome Laboratory, Upton, NY, USA. Email: [email protected] by policymakers. Increased public understanding of the costs and benefits of thera‐ peutic protein production in plants will be instrumental in increasing the acceptance, Funding information Biotechnology and Biological Sciences and thus the medical and veterinary impact, of this approach. Research Council; Margaret Claire Ryan Summary Fellowship Fund at the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs; U.S. Department Therapeutic recombinant proteins are a powerful tool for combating many diseases of Energy, Grant/Award Number: DE‐ which have previously been hard to treat. The most utilized expression systems are SC0012704 Chinese Hamster Ovary cells and Escherichia coli, but all available expression sys‐ tems have strengths and weaknesses regarding development time, cost, protein size, yield, growth conditions, posttranslational modifications and regulatory approval. The plant industry is well established and growing and harvesting crops is easy and affordable using current infrastructure. -

Gibson Assembly Cloning Guide, Second Edition

Gibson Assembly® CLONING GUIDE 2ND EDITION RESTRICTION DIGESTFREE, SEAMLESS CLONING Applications, tools, and protocols for the Gibson Assembly® method: • Single Insert • Multiple Inserts • Site-Directed Mutagenesis #DNAMYWAY sgidna.com/gibson-assembly Foreword Contents Foreword The Gibson Assembly method has been an integral part of our work at Synthetic Genomics, Inc. and the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) for nearly a decade, enabling us to synthesize a complete bacterial genome in 2008, create the first synthetic cell in 2010, and generate a minimal bacterial genome in 2016. These studies form the framework for basic research in understanding the fundamental principles of cellular function and the precise function of essential genes. Additionally, synthetic cells can potentially be harnessed for commercial applications which could offer great benefits to society through the renewable and sustainable production of therapeutics, biofuels, and biobased textiles. In 2004, JCVI had embarked on a quest to synthesize genome-sized DNA and needed to develop the tools to make this possible. When I first learned that JCVI was attempting to create a synthetic cell, I truly understood the significance and reached out to Hamilton (Ham) Smith, who leads the Synthetic Biology Group at JCVI. I joined Ham’s team as a postdoctoral fellow and the development of Gibson Assembly began as I started investigating methods that would allow overlapping DNA fragments to be assembled toward the goal of generating genome- sized DNA. Over time, we had multiple methods in place for assembling DNA molecules by in vitro recombination, including the method that would later come to be known as Gibson Assembly. -

Eukaryotic Expression

Molecular Biology Problem Solver: A Laboratory Guide. Edited by Alan S. Gerstein Copyright © 2001 by Wiley-Liss, Inc. ISBNs: 0-471-37972-7 (Paper); 0-471-22390-5 (Electronic) 16 Eukaryotic Expression John J. Trill, Robert Kirkpatrick, Allan R. Shatzman, and Alice Marcy Section A: A Practical Guide to Eukaryotic Expression . 492 Planning the Eukaryotic Expression Project . 493 What Is the Intended Use of the Protein and What Quantity Is Required? . 493 What Do You Know about the Gene and the Gene Product? . 496 Can You Obtain the cDNA? . 497 Expression Vector Design and Subcloning . 498 Selecting an Appropriate Expression Host . 501 Selecting an Appropriate Expression Vector . 506 Implementing the Eukaryotic Expression Experiment . 511 Media Requirements, Gene Transfer, and Selection . 511 Scale-up and Harvest . 514 Gene Expression Analysis . 515 Troubleshooting . 517 Confirm Sequence and Vector Design . 517 Investigate Alternate Hosts . 519 A Case Study of an Expressed Protein from cDNA to Harvest.......................................... 519 Summary . 521 Section B: Working with Baculovirus . 521 Planning the Baculovirus Experiment . 521 491 Is an Insect Cell System Suitable for the Expression of Your Protein? . 521 Should You Express Your Protein in an Insect Cell Line or Recombinant Baculovirus? . 522 Procedures for Preparing Recombinant Baculovirus . 524 Criteria for Selecting a Transfer Vector . 524 Which Insect Cell Host Is Most Appropriate for Your Situation? . 525 Implementing the Baculovirus Experiment . 527 What’s the Best Approach to Scale-Up? . 527 What Special Considerations Are There for Expressing Secreted Proteins? . 527 What Special Considerations Are There for Expressing Glycosylated Proteins? . 528 What Are the Options for Expressing More Than One Protein?.................................... -

The Transgenic Core Facility

Genetic modification of the mouse Ben Davies Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics Genetically modified mouse models • The genome projects have provided us only with a catalogue of genes - little is know regarding gene function • Associations between disease and genes and their variants are being found yet the biological significance of the association is frequently unclear • Genetically modified mouse models provides a powerful method of assaying gene function in the whole organism Sequence Information Human Mutation Gene of Interest Mouse Model Reverse Genetics Phenotype Gene Function How to study gene function Human patients: • Patients with gene mutations can help us understand gene function • Human’s don’t make particularly willing experimental organisms • An observational science and not an experimental one • Genetic make-up of humans is highly variable • Difficult to pin-point the gene responsible for the disease in the first place Mouse patients: • Full ability to manipulate the genome experimentally • Easy to maintain in the laboratory – breeding cycle is approximately 2 months • Mouse and human genomes are similar in size, structure and gene complement • Most human genes have murine counterparts • Mutations that cause disease in human gene, generally produce comparable phentoypes when mutated in mouse • Mice have genes that are not represented in other model organisms e.g. C. elegans, Drosophila – genes of the immune system What can I do with my gene of interest • Gain of function – Overexpression of a gene of interest “Transgenic -

Review on Applications of Genetic Engineering and Cloning in Farm Animals

Journal of Dairy & Veterinary Sciences ISSN: 2573-2196 Review Article Dairy and Vet Sci J Volume 4 Issue 1 - October 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ayalew Negash DOI: 10.19080/JDVS.2017.04.555629 Review on Applications of Genetic Engineering And Cloning in Farm animals Eyachew Ayana1, Gizachew Fentahun2, Ayalew Negash3*, Fentahun Mitku1, Mebrie Zemene3 and Fikre Zeru4 1Candidate of Veterinary medicine, University of Gondar, Ethiopia 2Candidate of Veterinary medicine, Samara University, Ethiopia 3Lecturer at University of Gondar, University of Gondar, Ethiopia 4Samara University, Ethiopia Submission: July 10, 2017; Published: October 02, 2017 *Corresponding author: Ayalew Negash, Lecturer at University of Gondar, College of Veterinary Medicine and science, University of Gondar, P.O. 196, Gondar, Ethiopia, Email: Abstract Genetic engineering involves producing transgenic animal’s models by using different techniques such as exogenous pronuclear DNA highly applicable and crucial technology which involves increasing animal production and productivity, increases animal disease resistance andmicroinjection biomedical in application. zygotes, injection Cloning ofinvolves genetically the production modified embryonicof animals thatstem are cells genetically into blastocysts identical and to theretrovirus donor nucleus.mediated The gene most transfer. commonly It is applied and recent technique is somatic cell nuclear transfer in which the nucleus from body cell is transferred to an egg cell to create an embryo that is virtually identical to the donor nucleus. There are different applications of cloning which includes: rapid multiplication of desired livestock, and post-natal viabilities. Beside to this Food safety, animal welfare, public and social acceptance and religious institutions are the most common animal conservation and research model. -

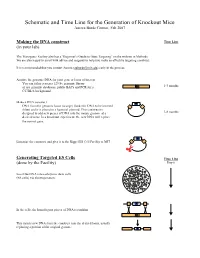

Schematic and Time Line for the Generation of Knockout Mice Aurora Burds Connor, Feb 2007

Schematic and Time Line for the Generation of Knockout Mice Aurora Burds Connor, Feb 2007 Making the DNA construct Time Line (in your lab) The Transgenic Facility also has a “Beginner’s Guide to Gene Targeting” on the website in Methods. We are also happy to assist with advice and reagents to help you make an effective targeting construct. It is recommended that you contact Aurora ([email protected]) early in the process. Acquire the genomic DNA for your gene or locus of interest You can either screen a 129/Sv genomic library 1-3 months or use genomic databases, public BACs and PCR for a C57BL/6 background Make a DNA construct. DNA from the genomic locus (orange) flanks the DNA to be inserted (blue) and it is placed in a bacterial plasmid. This construct is designed to add new pieces of DNA into the mouse genome at a 3-6 months desired locus. In a knockout experiment, the new DNA will replace the normal gene. Linearize the construct and give it to the Rippel ES Cell Facility at MIT Generating Targeted ES Cells Time Line (done by the Facility) Day 0 Insert the DNA into embryonic stem cells (ES cells) via electroporation. In the cells, the homologous pieces of DNA recombine. This inserts new DNA from the construct into the desired locus, usually replacing a portion of the original genome. Place the ES cells in selective media, allowing for the growth of cells containing the DNA construct. - The DNA construct has a drug-resistance marker Day 1-10 - Very few of the cells take up the construct – cells that do not will die because they are not resistant to the drug added to the media. -

Recent Advances in Genome Editing Tools in Medical Mycology Research

Journal of Fungi Review Recent Advances in Genome Editing Tools in Medical Mycology Research Sanaz Nargesi 1 , Saeed Kaboli 2,3,* , Jose Thekkiniath 4,*, Somayeh Heidari 5 , Fatemeh Keramati 6, Seyedmojtaba Seyedmousavi 5,7 and Mohammad Taghi Hedayati 1,5,* 1 Department of Medical Mycology, School of Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari 481751665, Iran; [email protected] 2 Department of Medical Biotechnology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan 4513956111, Iran 3 Cancer Gene Therapy Research Center, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan 4513956111, Iran 4 Fuller Laboratories, 1312 East Valencia Drive, Fullerton, CA 92831, USA 5 Invasive Fungi Research Center, Communicable Diseases Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari 481751665, Iran; [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (S.S.) 6 Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia 5756151818, Iran; [email protected] 7 Clinical Center, Microbiology Service, Department of Laboratory Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (M.T.H.) Abstract: Manipulating fungal genomes is an important tool to understand the function of tar- get genes, pathobiology of fungal infections, virulence potential, and pathogenicity of medically important fungi, and to develop novel diagnostics and therapeutic targets. Here, we provide an overview of recent advances in genetic manipulation techniques used in the field of medical mycol- Citation: Nargesi, S.; Kaboli, S.; ogy. Fungi use several strategies to cope with stress and adapt themselves against environmental Thekkiniath, J.; Heidari, S.; Keramati, effectors. For instance, mutations in the 14 alpha-demethylase gene may result in azole resistance in F.; Seyedmousavi, S.; Hedayati, M.T. -

An Improved Syringe Agroinfiltration Protocol to Enhance Transformation Efficiency by Combinative Use of 5-Azacytidine, Ascorbat

plants Article An Improved Syringe Agroinfiltration Protocol to Enhance Transformation Efficiency by Combinative Use of 5-Azacytidine, Ascorbate Acid and Tween-20 Huimin Zhao 1, Zilong Tan 2, Xuejing Wen 2 and Yucheng Wang 1,2,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China; [email protected] 2 Key Laboratory of Biogeography and Bioresource in Arid Land, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (Z.T.); [email protected] (X.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-451-82190607 Academic Editor: Milan S. Stankovic Received: 1 January 2017; Accepted: 9 February 2017; Published: 14 February 2017 Abstract: Syringe infiltration is an important transient transformation method that is widely used in many molecular studies. Owing to the wide use of syringe agroinfiltration, it is important and necessary to improve its transformation efficiency. Here, we studied the factors influencing the transformation efficiency of syringe agroinfiltration. The pCAMBIA1301 was transformed into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves for investigation. The effects of 5-azacytidine (AzaC), Ascorbate acid (ASC) and Tween-20 on transformation were studied. The β-glucuronidase (GUS) expression and GUS activity were respectively measured to determine the transformation efficiency. AzaC, ASC and Tween-20 all significantly affected the transformation efficiency of agroinfiltration, and the optimal concentrations of AzaC, ASC and Tween-20 for the transgene expression were identified. Our results showed that 20 µM AzaC, 0.56 mM ASC and 0.03% (v/v) Tween-20 is the optimal concentration that could significantly improve the transformation efficiency of agroinfiltration. -

Production of Lentiviral Vectors Using Novel, Enzymatically Produced, Linear DNA

Gene Therapy (2019) 26:86–92 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-018-0056-1 ARTICLE Production of lentiviral vectors using novel, enzymatically produced, linear DNA 1 2,3 4 4 4 Rajvinder Karda ● John R. Counsell ● Kinga Karbowniczek ● Lisa J. Caproni ● John P. Tite ● Simon N. Waddington1,5 Received: 17 October 2018 / Revised: 27 November 2018 / Accepted: 5 December 2018 / Published online: 14 January 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract The manufacture of large quantities of high-quality DNA is a major bottleneck in the production of viral vectors for gene therapy. Touchlight Genetics has developed a proprietary abiological technology that addresses the major issues in commercial DNA supply. The technology uses ‘rolling-circle’ amplification to produce large quantities of concatameric DNA that is then processed to create closed linear double-stranded DNA by enzymatic digestion. This novel form of DNA, Doggybone™ DNA (dbDNA™), is structurally distinct from plasmid DNA. Here we compare lentiviral vectors production from dbDNA™ and plasmid DNA. Lentiviral vectors were administered to neonatal mice via intracerebroventricular fi 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: injection. Luciferase expression was quanti ed in conscious mice continually by whole-body bioluminescent imaging. We observed long-term luciferase expression using dbDNA™-derived vectors, which was comparable to plasmid-derived lentivirus vectors. Here we have demonstrated that functional lentiviral vectors can be produced using the novel dbDNA™ configuration for delivery in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, this could enable lentiviral vector packaging of complex DNA sequences that have previously been incompatible with bacterial propagation systems, as dbDNA™ technology could circumvent such restrictions through its phi29-based rolling-circle amplification. -

Highly Efficient Protoplast Isolation and Transient Expression System

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Highly Efficient Protoplast Isolation and Transient Expression System for Functional Characterization of Flowering Related Genes in Cymbidium Orchids Rui Ren 1 , Jie Gao 1, Chuqiao Lu 1, Yonglu Wei 1, Jianpeng Jin 1, Sek-Man Wong 2,3,4, Genfa Zhu 1,* and Fengxi Yang 1,* 1 Guangdong Key Laboratory of Ornamental Plant Germplasm Innovation and Utilization, Environmental Horticulture Research Institute, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China; [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (J.J.) 2 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore (NUS), 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Singapore; [email protected] 3 National University of Singapore Suzhou Research Institute (NUSRI), Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou 215000, China 4 Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, National University of Singapore, 1 Research Link, Singapore 117604, Singapore * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.Z.); [email protected] (F.Y.) Received: 28 February 2020; Accepted: 24 March 2020; Published: 25 March 2020 Abstract: Protoplast systems have been proven powerful tools in modern plant biology. However, successful preparation of abundant viable protoplasts remains a challenge for Cymbidium orchids. Herein, we established an efficient protoplast isolation protocol from orchid petals through optimization of enzymatic conditions. It requires optimal D-mannitol concentration (0.5 M), enzyme concentration (1.2 % (w/v) cellulose and 0.6 % (w/v) macerozyme) and digestion time (6 h). With this protocol, the highest yield (3.50 107/g fresh weight of orchid tissue) and viability (94.21%) of × protoplasts were obtained from flower petals of Cymbidium. -

Grapevine Protoplasts As a Transient Expression System for Comparison

Grapevine Protoplasts as a Transient Expression System for Comparison of Stilbene Synthase Genes Containing cGMP-Responsive Promoter Elements Ilka Brehm, Regina Preisig-Müller and Helmut Kindi Fachbereich Chemie der Philipps-Universität, D-35032 Marburg, Germany Z. Naturforsch. 54c, 220-229 (1999) received December 15, 1998/January 7, 1999 cGMP, Grapevine Protoplasts, Pine, Promoter, Elicitor-Responsive, Stilbene Synthase Gene, Vitis A method for preparing elicitor-responsive protoplasts from grapevine cells kept in suspen sion culture was established. The protoplasts were employed in order to perform transient gene expression experiments produced by externally added plasmids. Using the gene coding for bacterial ß-glucuronidase as the reporter gene, the transient expression under the control of various promoters of stilbene synthase genes were analyzed. The elicitor-responsiveness of promoters from grapevine genes and heterologous promoters were assayed: the grapevine stilbene synthase gene VST-1 and pine stilbene synthase genes PST-1, PST-2 and PST-3. Compared to the expression effected by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S RNA-promoter, the stilbene synthase promoters caused a 2-5-fold increase in GUS-activity. Incubation of transformed protoplasts with fungal cell wall further stimulated the stilbene synthase promot ers but not the 35S RNA-promoter. An even more pronounced differentiation between the promoters was observed when cGMP was included in the transient expression assays. Instead of treating transformed protoplasts with fungal cell wall we administered simultaneously cGMP and the plasmid to be tested. The cGMP-responsive increase was (a) specific concern ing the nucleotide applied, (b) characteristic of grapevine protoplasts, and (c) not seen with shortened promoter-GUS constructs or GUS under the control of the 35S RNA-promoter.