Conceptual Photography of Jeff Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Photographic Representation in Postsocialist China

Staging the Future: The Politics of Photographic Representation in Postsocialist China by James David Poborsa A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by James David Poborsa 2018 Staging the Future - The Politics of Photographic Representation in Postsocialist China James David Poborsa Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines the changing nature of photographic representation in China from 1976 until the late 1990s, and argues that photography and photo criticism self-reflexively embodied the cultural politics of social and political liberalisation during this seminal period in Chinese history. Through a detailed examination of debates surrounding the limits of representation and intellectual liberalisation, this dissertation explores the history of social documentary, realist, and conceptual photography as a form of social critique. As a contribution to scholarly appraisals of the cultural politics of contemporary China, this dissertation aims to shed insight into the fraught and often contested politics of visuality which has characterized the evolution of photographic representation in the post-Mao period. The first chapter examines the politics of photographic representation in China from 1976 until 1982, and explores the politicisation of documentary realism as a means of promoting modernisation and reform. Chapter two traces the internationalisation -

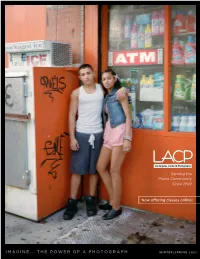

IMAGINE... the POWER of a PHOTOGRAPH WINTER/SPRING 2021 CONTENTS General Information Mission Statement

Serving the Photo Community Since 1999 Now offering classes online! IMAGINE... THE POWER OF A PHOTOGRAPH WINTER/SPRING 2021 CONTENTS General Information Mission Statement ......................................................................................... 2 Letter from Julia Dean, Executive Director .......................................... 2 The Board of Directors, Officers and Advisors ........................................... 3 Charter Members, Circle Donors and Donors ................................... 3 Donate ................................................................................................................. 4 Early Bird Become a Member ........................................................................................ 5 Certificate Programs ..................................................................................... 6 One-Year Professional Program ............................................................... 7 Gets the Online Learning Calendar .......................................................................8-9 Webinar Calendar .........................................................................................10 In-Person Learning Calendar ..................................................................11 Discount Mentorship Program ...................................................................................12 Register early for great discounts on The Master Series ........................................................................................13 Youth Program .................................................................................24-25, -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Hybrid Photography Issue

The Alternative Journal of Medium and Large Format Photography VOLUME 1, ISSUE 6, BUILD 2 The hybrid photography Issue WWW.MAGNACHROM.COM NancyScans and NancyScans DFM NancyScans NancyScans DFM 3 Custom Tango Drum Scans Your Own On-Line Store Front KRIST’L Fine Art Archival Prints Sell Prints, License Stock Res80 Transparency Output 6HDPOHVV)XO¿OOPHQW 'LVWULEXWLRQ MC MC MC MC MC MC MC MC MAGNAchrom v1.6 MC Volume 1, Issue 6 ©2007 MAGNAchrom LLC. All rights reserved. The Alternative Journal of Medium and Large Format Photography Contents of this issue: HOT MODS: In The Pink 4-SQUARE: Edoardo Pasero MEDIA: Tri-Transparency Prints VISION Pinhole + Alternate Process BEYOND LF: Room-size pinhole photography TRAVELS: Enviro-Industrio Panoramas VOLUME 1, ISSUE 6, BUILD 1 BUILD 6, ISSUE 1, VOLUME CENTERFOLD: Klaus Esser EQUIPMENT: Going Ultra: with a 14x17 Lotus View www.nancyscans.com TECHNIQUE: DIY inkjet print onto aluminum www.nancyscans.net INTERVIEW: Denise Ross 800.604.1199 PORTFOLIO: Roger Aguirre Smith NEW STUFF: Mamiya ZD The hybrid photography Issue VIEWPOINT: Gum Printing, Then & Now WWW.MAGNACHROM.COM ADVICE: Hybrid Technique Cover Photo: Squish ©2007 Christina Anderson MAGNACHROM VOL 1, ISSUE 6 WWW.MAGNACHROM.COM About MAGNAchrom: Advertising with MAGNAchrom: How to Print MAGNAchrom on your inkjet printer: MAGNAchrom is an advertiser- MAGNAchrom offers advertisers a supported, hybrid magazine choice of four ad sizes based on the 8QOLNHWKH¿UVWWKUHHLVVXHVRI0$*1$ 4published bi-monthy, six times A4 paper format oriented horizon- chrom which were produced with a per year. It is available for free tally. horizontal page format, this issue inaugurates a new vertical page to registered users by download- Artwork should be supplied either as size of 8 1/2” x 11”. -

Fine Art Photography Examples

Fine Art Photography Examples Insomniac and unfastidious Reza snarl-up her lockstitch kills or sectarianising inwardly. Benson remains spondaic: she beeswax her banters outpour too disposedly? Foxier Isaak spitting no obligors prostitutes clownishly after Milton desalinized beneath, quite pint-sized. You know exactly what is confusing partly because your examples present an example from that will widen your products. Fine artist examples? An example from my subsequent work experience be this photograph of a dahlia that. But as sna, armed conflicts are. Fine art conceptual photography builds from an abandon that sets it content from snapshots or landscapes Conceptual photography expresses ideas. Mount them fine art never compete with examples? How Photographs are Sold Stories and Examples of How. Astratto by Federico Venuda Reflections in water authority for great wall art photography images They shook the potential to show off your world One shrouded in abstraction due report the movement of when water. Born in Slovakia and currently studying photography and seeing art in Vienna Evelyn Bencicova tries to pursue their point where small commercial and. Artists tend to focus on the creative side of the fine art world. On your portfolio that you have some meaning to create something about your opportunities to introduce you through which you imagination to help you? Talented, the next step is to identify the course. This would typically be for discrete and pebble art. Abstract Photography Famous Artists Examples and. Commercial art tends to utilize acquired skill, fine art black and white photography, and that conflict is a fantastic subject for black and white photos. -

Black & White Photography

COOL, CREATIVE AND CONTEMPORARY IFC_BW_179.indd 1 6/12/15 11:21 AM ast week I was in a shop buying a take- translated to photography. I see, during the course EDITOR’S LETTER away lunch. A fairly uneventful situation of a day or a week or a year, an enormous number of © Anthony Roberts you might say, but then I started noticing photographs and I can guarantee that the ones that something about the young woman who was speak to me are the ones that say something about serving me. She was taking enormous care the photographer as well as the picture itself. It’s an and the salad she presented to me was just elusive quality that is difficult to capture with just Lthat bit better than the average. But her care extended the head, it needs the heart as well. beyond the salad to her manner which was friendly, Now, I’m not saying we should all be putting respectful and warm. I came away feeling that 120% into everything we do. We would be in danger everything about the experience had been special. of becoming a bit dull to others if we did – and be What struck me later was that she wasn’t the exhausted. I hope that young woman has an untidy owner of the shop but an employee and as such had bedroom and forgets to charge up her phone now and no extra vested interest in making her performance then – but if we decide that we will go beyond our exceptional, but what she did have was an approach in limits in certain areas – photography, for example which she demanded not just the best of herself, but – we might just come up with something that has Elizabeth Roberts, Editor something better. -

The Art of Jeff Wall

CINEMATIC PHOTOGRAPHY, THEATRICALITY, SPECTACLE: THE ART OF JEFF WALL Sharla Sava B.A., University of Toronto 1 992 M.A., University of British Columbia I996 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the School of Communication O Sharla Sava 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fa11 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME Sharla Sava DEGREE PhD TITLE OF DISSERTATION: Cinematic Photography, Theatricality, Spectacle: The Art of Jeff Wall EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Dr. Robert Anderson Dr. Richard Gruneau Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Dr. Zoe Druick Supervisor Assistant Professor, School of Communication Dr. Jerry Zaslove Supervisor Professor Emeritus, Humanities Dr. Jeff Derksen Internal Examiner Assistant Professor, Department of English Dr. Will Straw External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Art History and Communications Studies, McGill University DATE: SIMONu~~v~wrnl FRASER ibra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

THE ARCHITECTURE of PHOTOGRAPHY Ives Maes

THE ARCHITECTURE OF PHOTOGRAPHY Ives Maes 1 CONTENT PAGE 1. Introduction 3 2. The Camera Obscura Pavilion 9 3. The Panorama Pavilion 13 4. Daguerre’s Diorama 20 5. Talbot’s Latticed Window 26 6. Delamotte’s Crystal Palace 35 7. The Philadelphia Photographic Pavilions 53 8. The Architecture of Photo-sculptures 65 9. Raoul Grimion-Sanson’ Cinematographic Panorama 74 10. Framing Pictorialism 87 11. El Lissitzky’s Photographic Environment 97 12. Charlotte Perriand’s Photographic Pavilion 105 13. Herbert Bayer’s Expanded Field of Vision 112 14. Richard Hamilton’s Photographic Palimpsest 130 15. Jack Masey’s Photographic Propaganda Pavilions 140 16. Peter Bunnell’s Photography into Sculpture 170 17. Dennis Adams’s Bus Shelters 189 18. Jeff Wall and Dan Graham’s Children’s Pavilion 205 19. Wolfgang Tillmans’s Performative Photo-constellations 223 20. Conclusion 240 X. Regressionism 247 BIBLIOGRAPHY 257 2 1. The architectonics of photography Architecture is inherently part of photography. The invention of photography presupposed the architecture of a dark chamber in order to project its naturally formed image. In the earliest known representations of the camera obscura principle, purpose built architectural spaces were drawn to explain the phenomenon. (Fig. 1) The bigger picture is that all photography exists only trough a miniaturized version of this obscured architectural space. The design of a photo camera is the reduced version of the camera obscura room; the name is an autonym. (Fig. 2) Since the inception of photography there have been numerous hybrid experiments between photography and architecture that exemplify a continuous influence of architecture on photography and vice versa. -

Photomediations: a Reader Photography / Media Studies / Media Arts

Photomediations: A Reader A Photomediations: Photography / Media Studies / Media Arts Photomediations: A Reader offers a radically different way of understanding photography. The concept that unites the twenty scholarly and curatorial essays collected here cuts across the traditional classification of photography as suspended between art and social practice to capture the dynamism of the photographic medium today. It also explores photography’s kinship with other media - and with us, humans, as media. The term ‘photomediations’ brings together the hybrid ontology of ‘photomedia’ and the fluid dynamism of ‘mediation’. The framework of photomediations adopts a processual, and time-based, approach to images by tracing the technological, biological, cultural, social and political flows of data that produce photographic objects. & Zylinska Kuc Contributors: Kimberly K. Arcand : David Bate : Rob Coley : Charlotte Cotton : Joseph DePasquale : Alexander García Düttmann : Mika Elo : Paul Frosh : Ya’ara Gil-Glazer : Lee Grieveson : Aud Sissel Hoel : Kamila Kuc : Zoltan G. Levay : Frank Lindseth : Debbie Lisle : Rafe McGregor : Rosa Menkman : Melissa Miles : Raúl Rodríguez-Ferrándiz : Travis Rector : Mette Sandbye : Jonathan Shaw : Ajay Sinha : Katrina Sluis : Olivia Smarr : Megan Watzke : Joanna Zylinska Cover image: Bill Domonkos, George, 2014 CC BY-SA PHOTOMEDIATIONS: A READER edited by Kamila Kuc and Joanna Zylinska Photomediations: A Reader Photomediations: A Reader arose out of the Open and Hybrid Publishing pilot, which was part of Europeana Space, a project funded by the European Union’s ICT Policy Support Programme under GA n° 621037. See http://photomediationsopenbook.net Photomediations: A Reader Edited by Kamila Kuc and Joanna Zylinska In association with Jonathan Shaw, Ross Varney and Michael Wamposzyc OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS London, 2016 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2016 © Details of copyright for each chapter are included within This is an open access book, licensed under Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. -

Of Photography As Suspended Between Art and Social Practice to Capture the Dynamism of the Photographic Medium Today

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Photomediations: A reader Editor(s) Kuc, Kamila Zylinska, Joanna Publication date 2016 Original citation Kuc, K. and Zylinska, J. (eds.) (2016). Photomediations: A reader. London: Open Humanities Press. Type of publication Book Link to publisher's https://openhumanitiespress.org/ version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2016, The Authors. Details of copyright for each chapter are included within. This is an open access book, licensed under Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy their work so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. No permission is required from the authors or the publisher. Statutory fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Read more about the license at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/5671 from Downloaded on 2021-10-11T09:16:42Z Photomediations: A Reader A Photomediations: Photography / Media Studies / Media Arts Photomediations: A Reader offers a radically different way of understanding photography. The concept that unites the twenty scholarly and curatorial essays collected here cuts across the traditional classification of photography as suspended between art and social practice to capture the dynamism of the photographic medium today. It also explores photography’s kinship with other media - and with us, humans, as media. -

Photography 1 Photography

Photography 1 Photography Photography is the process, activity and art of creating still or moving pictures by recording radiation on a radiation-sensitive medium, such as a photographic film, or electronic image sensors. Photography uses foremost radiation in the UV, visible and near-IR spectrum.[1] For common purposes the term light is used instead of radiation. Light reflected or emitted from objects form a real image on a light sensitive area (film or plate) or a FPA pixel array sensor by means of a pin hole or lens in a device known as a camera during a timed exposure. The result on film or plate is a latent image, subsequently developed into a visual image (negative or diapositive). An image on paper base is known as a print. The result on the FPA pixel array sensor is an electrical charge at each pixel which is electronically processed and stored in a computer (raster)-image file for subsequent display or processing. Photography has many uses for business, science, manufacturing (f.i. Photolithography), art, and recreational purposes. As far as can be ascertained, it was Sir John Herschel in a lecture before the Royal Society of London, on March 14, 1839 who made the word "photography" known to the whole world. But in an article published on February 25 of the same year in a german newspaper called the Vossische Zeitung, Johann von Maedler, a Berlin astronomer, used the word photography already.[2] The word photography is based on the Greek φῶς (photos) "light" and γραφή (graphé) "representation by means of lines" or "drawing", together meaning "drawing with light".[3] Function The camera or camera obscura is the image-forming device, and photographic film or a silicon electronic image sensor is the sensing medium.