The Minnesota Review the Minnesota Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Hop Club Songs

Hip Hop Club Songs Did you Know? The credit of coining the term 'Hip-Hop' lies with Keith 'Cowboy' Wiggins, a member of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. Around 1978, he used to tease his friend who was in the US Army by singing hip/hop/hip/hop. He was mimicking the cadence rhythm of the soldiers. Initially known as Disco Rap, hip-hop music is a stylized download mp3 rocket pro free 2010 rhythmic music form which contains rapping and beat boxing as its elements. This music developed as a part of the 'hip-hop culture' in New York, particularly among the African-Americans. Today, hip hop music has become extremely popular among the masses. With the commercialization of this genre of music, a new era of talent paved its path to give music a new feel and rhythm by using words in the interim as a form of expression. Artists like Snoop Dog, Eminem, Nicki Minaj, Black- Eyed Peas have popularized this particular genre even further. Certain artists, who were known for performing other genres also started experimenting with rap and hip-hop. Couple of such examples would be Beyonce and none other than the King of Pop, Michael Jackson. Another factor that has added to hip-hop's popularity is that this music is ideal for nightclubs and dance floors. So, are you arranging one such party for your friends and wondering which songs to play? Then here is a list of various hip-hop club songs that you can play. ? Baby Don't Do It - Lloyd ? Best Kept Secret - Raheem DeVaughn ? Bedroom Walkin' - Ne-Yo ? Tonight - Jason Derulo ? Almost There - Alicia Keys ? Stillettos And A Tee - Bobby Valentino ? Help Somebody - Maxwell Feat. -

Pdf, 331.08 KB

The Adventure Zone: Commitment – Episode 3 Published on November 16th, 2017 Listen on TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Griffin: Let‘s just get into it! Let‘s just get on it. Travis: Roll your ball! Griffin: Roll that fuckin‘ ball! Clint: Are we… are we good, or should we just charge right in? Griffin: Let‘s just do it! We‘re about to fight a big fucking robot unicorn and I‘m ready! Travis: Yeah, if you want to know the ―Previously on…‖ go back and re- listen to the episode! Clint: Good point. Griffin: Things Remy has done since he got superpowers: jumped into a wall, and then solved a riddle from a big St. Peter. Things he has not done: jumped and fought. It‘s time. It is now. Justin: I would appreciate reminding us of what we‘re doing. Travis: No, we‘re fighting a unicorn and a robot or whatever, let‘s gooo! Clint: I‘ll make it very simple. You‘re in a field of lilies of the valley; the golden road has kinda fallen into disrepair. Right ahead of you is this thick line of trees. A robot Salome has come in, riding on a unicorn. She jumps off the unicorn, she drops John the Baptist‘s head—ah, I forgot to put John the Baptist‘s head on the— Travis: No, but let‘s just say, Dad— Clint: —the map. Travis: Your map game is— Griffin: It‘s improving! You‘re gonna be— Travis: And I just want to say, I love how you see all the little flowers everywhere. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

Author Notes - Ell Leigh Clarke June 28, 2018

Full Author’s Notes From Ascension, Book 12 The Ascension Myth Author Notes - Ell Leigh Clarke June 28, 2018 Thank yous Massive thanks as always goes out to MA, for not cancelling my show. (EDIT MA: Why would I cancel this awesomeness??) Yep, we’ve survived a year. And twelve Molly books! WOOT! While there are no immediate plans to continue the series now that we’ve wrapped up Molly 12, there is nothing to say that we won’t start a new Molly series down the line. For now, we’re working on other concepts. More on those below. Huge thank yous also go to Steve “Zen Master” Campbell and the JIT team who work tirelessly to make sure that all slips are caught and corrected, the files are uploaded on time. Thank you so much folks. I truly appreciate all your efforts. :) Reviewers Massive thanks also goes out to our hoard of Amazon reviewers. It’s because of you that we get to do this full time. Without your five-star reviews and thoughtful words on Amazon we simply wouldn’t have enough folks reading these space shenanigans to be able to write full time. You are the reason these stories exist and you have no idea how frikkin’ grateful I am to you. Truly, thank you. Readers and FB page supporters Last, and certainly by no means least, I’d like to thank you for reading this book… and all the others. Your enthusiasm for the world, and the characters, is heart-warming. Your words of encouragement, and demands for the next episode, are the things that often stay in my mind as I flick from checking the facebook page to the scrivener file when I start each writing session. -

Representations of African American Women on Reality Television After the Great Recession

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-11-2015 Representations of African American Women on Reality Television After the Great Recession Steven Herro Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Recommended Citation Herro, Steven, "Representations of African American Women on Reality Television After the Great Recession." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/55 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN ON REALITY TELEVISION AFTER THE GREAT RECESSION by STEVEN K. HERRO Under the Direction of Marian Meyers, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This project is animated by two related probLems. First, there are reLativeLy few studies of the ways that African American women are represented on reaLity teLevision. Second, the current Literature about representations of BLack women on reality television compLetely ignores the Great Recession as an important contextual factor. In this study, I pair the Constant Comparative Method of textuaL anaLysis with discourse analysis to answer the question: “How does reaLity teLevision represent African American women in terms of gender, race, and cLass in the context of the aftermath of the Great Recession?” I closeLy anaLyzed reaLity teLevision programs with the highest ratings in 2012: The Voice, American Idol, Survivor, The Biggest Loser, and The Real Housewives of Atlanta. To better understand how Black wom- en are represented on these shows, I contextualize my analysis in terms of intersectionality, post-racism, post-sexism, and neoLiberaLism. -

Dr. Dre the Next Episode

The Next Episode Dr. Dre La-da-da-da-dahh It's the motherfucking D-O-double-G (SNOOP DOGG!) La-da-da-da-dahh You know I'm mobbin' with the D.R.E. (YEAH YEAH YEAH You know who's back up in this MOTHERFUCKER!) What what what what? (So blaze the weed up then!) Blaze it up, blaze it up! (Just blaze that shit up nigga, yeah, 'sup Snoop??) Top Dogg, bite 'em all, nigga burn the shit up D-P-G-C my nigga turn that shit up C-P-T, L-B-C, yeah we hookin' back up And when they bang this in the club baby you got to get up Thug niggas drug dealers yeah they givin' it up Lowlife, yo' life, boy we livin' it up Takin' chances while we dancin' in the party for sure Slip my hoe a forty-fo' and she got in the back do' Bitches lookin' at me strange but you know I don't care Step up in this motherfucker just a-swangin' my hair Bitch quit talkin', Crip walk if if you down with the set Take a bullet with some dick and take this dope from this jet Out of town, put it down for the Father of Rap And if yo' ass get cracked, bitch shut yo' trap Come back, get back, that's the part of success If you believe in the X you'll be relievin' your stress La-da-da-da-dahh It's the motherfuckin' D.R.E. (Dr. -

Greatest Generation During Maxfundrive 2020

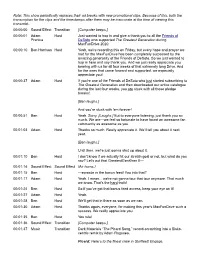

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Computer beeps.] 00:00:01 Adam Host Just wanted to hop in and give a thank-you to all the Friends of Pranica DeSoto who supported The Greatest Generation during MaxFunDrive 2020. 00:00:10 Ben Harrison Host Yeah, we're recording this on Friday, but every hope and prayer we had for the MaxFunDrive has been completely surpassed by the amazing generosity of the Friends of DeSoto. So we just wanted to hop in here and say thank you. And we just really appreciate you bearing with us for all four weeks of that extremely long Drive. And for the ones that came forward and supported, we especially appreciate you! 00:00:37 Adam Host If you're one of the Friends of DeSoto who just started subscribing to The Greatest Generation and then downloaded our entire catalogue during the last four weeks, you are stuck with all those pledge breaks! [Ben laughs.] And you're stuck with 'em forever! 00:00:51 Ben Host Yeah. Sorry. [Laughs.] But to everyone listening, just thank you so much. We are—we feel so fortunate to have found an awesome fan community as awesome as you. 00:01:03 Adam Host Thanks so much. Really appreciate it. We'll tell you about it next year. [Ben laughs.] Until then, we're just gonna shut up about it. -

Episode Five: Bogdanovich, the Misunderstood

EPISODE FIVE: BOGDANOVICH, THE MISUNDERSTOOD BURT REYNOLDS FROM THE TONIGHT SHOW: We have a mutual friend of course, Peter Bogdanovich. ORSON WELLES FROM THE TONIGHT SHOW: That’s right. As a matter of fact, you have me to thank for the fact that you were asked to be in the picture that was probably the least successful of any of your past. BEN MANKIEWICZ: That’s Orson Welles and Burt Reynolds on The Tonight Show back in 1978. The most popular late-night talk show of all time. Regularly seen in more than seven million homes. Reynolds was a guest host, sitting in for Johnny Carson. Reynolds had been in Peter’s last two movies. Both flops. ORSON WELLES FROM THE TONIGHT SHOW: My feeling was that the picture needed you. BURT REYNOLDS FROM THE TONIGHT SHOW: No, it needed a lot more. BEN MANKIEWICZ: Burt Reynolds was really famous at this point. 1978 was the first of five consecutive years when he was the most bankable movie star in the country. Orson, of course, was a famous director and actor. And one of Peter’s closest friends. Burt’s jokes Peter could handle. The jokes from Orson devastated him. PETER BOGDANOVICH: Yeah, they'd said some unpleasant things about me. Yeah, I was watching it. I sent Orson a note the next day saying, I was watching, I tuned in to see what you thought, how you guys were doing. Something like that. BEN MANKIEWICZ: Peter is telling me this story late last summer - 41 years had passed. And it’s still hard for him. -

Liste Collection En Vente CD Vinyl Hip Hop Funk Soul Crunk Gfunk Jazz Rnb HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM PRIX Négociable En Lot

1 Liste collection en vente CD Vinyl Hip Hop Funk Soul crunk GFunk Jazz Rnb HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM PRIX négociable en lot Type Prix Nom de l’artiste Nom de l’album de Genre Année Etat Qté média + de hits disco funk 2CD Funk 2001 1 12 2pac How do u want it CD Single Hip Hop 1996 1 5,50 2pac Ru still down 2CD Hip Hop 1997 1 14 2pac Until the end of time CD Single Hip Hop 2001 1 1,30 2pac Until the end of time CD Hip Hop 2001 0 5,99 2 pac Loyal to the game CD Hip Hop 2004 1 4,99 2 Pac Part 1 THUG CD Digi Hip Hop 2007 1 12 50 Cent Get Rich or Die Trying CD Hip Hop 2003 1 2,90 50 CENT The new breed CD DVD Hip Hop 2003 1 6 50 Cent The Massacre CD Hip Hop 2005 1 1,90 50 Cent The Massacre CD dvd Hip Hop 2005 0 7,99 50 Cent Curtis CD Hip Hop 2007 0 3,50 50 Cent After Curtis CD Diggi Hip Hop 2007 1 4 50 Cent Self District CD Hip Hop 2009 0 3,50 100% Ragga Dj Ewone CD 2005 1 7 Reggaetton 504 BOYZ BALLERS CD Hip Hop 2002 US 1 6 Aaliyah One In A Million CD Hip Hop 1996 1 14,99 Aaliyah I refuse & more than a CD single RNB 2001 1 8 woman Aaliyah feat Timbaland We need a resolution CD Single RNB 2001 1 5,60 2 Aaliyah More than a woman Vinyl Hip HOP 2001 1 5 Aaliyah CD Hip Hop 2001 2 4,99 Aaliyah Don’t know what to tell ya CD Single RNB 2002 1 4,30 Aaliyah I care for you 2CD RNB 2002 1 11 AG The dirty version CD Hip Hop 1999 Neuf 1 4 A motown special VINYL Funk 1977 1 3,50 disco album Akon Konvikt mixtape vol 2 CD Digi Hip Hop 1 4 Akon trouble CD Hip hop 2004 1 4,20 Akon Konvicted CD Hip Hop 2006 1 1,99 Akon Freedom CD Hip Hop 2008 1 2 Al green I cant stop CD Jazz 2003 1 1,90 Alicia Keys Songs in a minor (coffret CD Single Hip Hop 2001 1 25 Taiwan) album TAIWAN Maxi Alici Keys The Diary of CD Hip Hop 2004 1 4,95 Allstars deejay’s Mix dj crazy b dee nasty 2CD MIX 2002 1 3,90 eanov pone lbr Alyson Williams CD RNB 1992 1 3,99 Archie Bell Tightening it up CD Funk 1994 Us 10 6,50 Artmature Hip Hop VOL 2 CD Hip Hop 2015 1 19 Art Porter Pocket city CD Funk 1992 1 7 Ashanti CD RNB 2002 1 6 Asher Roth I love college VINYL Hip Hop 2009 1 8,99 A.S.M. -

Pop Fiction 2019 Song List

I Love Rock and Roll - Joan Jett Welcome to the Jungle - Guns N’ Roses I'm Gonna Be (I Would Walk 500 Miles) - We Belong Together - Pat Benatar The Proclaimers You Dropped a Bomb on Me - The Gap I've Had The Time of My Life - Dirty Band Dancing/Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes You Give Love a Bad Name - Bon Jovi I Wanna Dance with Somebody - Whitney You Make My Dreams Come True - Hall & Houston Oats Jack and Diane - John Cougar Melencamp You Shook Me All Night Long - AC/DC Jenny (867-5309) - Tommy Tutone You Spin Me Around - Dead or Alive Jessie’s Girl - Rick Springfield You're the Inspiration - Chicago Jump - Van Halen Jungle Love - Morris Day and the Time 90s Just Can’t Get Enough - Depeche Mode All Mixed Up - 311 Kids in America - Kim Wild All The Small Things - Blink 182 Kiss - Prince As Long as You Love Me - Backstreet Boys Let the Music Play - Shannon Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-lot Let's Dance - David Bowie Buddy Holly - Weezer Like a Virgin - Madonna California Love - 2Pac & Dr. Dre Livin’ On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Don't Look Back in Anger - Oasis Love Shack - B-52s Fresh Pince of Bell Air Theme - DJ Jazzy Material Girl - Madonna Jeff & the Fresh Prince (Will Smith) Modern Love - David Bowie Gettin' Jiggy Wit It - Will Smith Never Gonna Give You Up - Rick Astley Give It Away Now - Red Hot Chili Peppers New Sensation - INXS Humpty Dance - Digital Underground (You're My) Obsession - Animotion I Want it That Way - Backstreet Boys Open Your Heart - Madonna Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Our House - Madness I'm Too Sexy - Right Said Fred Pour Some Sugar On Me - Def Leppard Insane in the Brain - Cypress Hill Pretty Young Thing (P.Y.T.) - Michael Jump Around - House of Pain Jackson Kiss Me - 6 Pence None the Richer Purple Rain - Prince Last Christmas - Wham/George Michael Raspberry Beret - Prince Livin’ La Vida Loca - Ricky Martin Rebel Yell - Billy Idol Love Fool - The Cardigans Relax - Frankie Goes To Hollywood My Own Worst Enemy - Lit Rhythm is Gonna Get You - Gloria Estefan & O.P.P. -

Ep #39: Friday Coach Like Full Episode

Ep #39: Friday Coach Like Full Episode Transcript With Your Host Brooke Castillo The Life Coach School Podcast with Brooke Castillo Welcome to The Life Coach School podcast where it's all about real clients, real problems and real coaching. Now, your host, master coach instructor, Brooke Castillo. Hi everyone. Welcome to 2015. You may be listening to this in 2016 because once you put a podcast out there, it's out there forever. For those of you who listen to this real time, every Thursday, some of you have told me that you're always excited to get the next episode on Thursday so for those of you who have been waiting for this episode welcome to 2015. I am thrilled that we are starting a brand new year. I love a fresh start, new goals, new excitement and that's totally where I am. I think 2015 is going to be epic. I have decided to do something a little bit different with this episode because it's the first time I'm recording in 2015. One of the things that I do for everybody who's on my list is I send out an email every Friday called, "Friday Coach Like," and it's basically just a little summary of a coaching idea or of a thought. Or of a concept and it's just a little snack. A little bite-size morsel. Sometimes it's about something that's going on at the school but most of the time it's just a little bit of insight for you to take throughout your week into your weekend. -

Public-Scholarship-And-Representation Fri, 1/22 1:31PM 41:14

public-scholarship-and-representation Fri, 1/22 1:31PM 41:14 SUMMARY KEYWORDS scholarship, public, religion, scholar, folks, people, book, nerds, writing, simran, included, piece, calendars, teaching, work, podcast, shit, true, drag race, islamophobic SPEAKERS Simpsons, Derry Girls, Krusty the Klown, Megan Goodwin, Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst 00:17 This is Keeping It 101, a killjoy's introduction to religion podcast. This season our work is made possible in part through a generous grant from the New England Humanities Consortium and with additional support from the University of Vermont's Humanities Center. We are grateful to live, teach, and record on the ancestral and unseeded lands of the Abenaki, Wabenaki, and Aucocisco peoples. M Megan Goodwin 00:38 What's up, nerds? Hi, hello, I'm Megan Goodwin, a scholar of American religions, race. and gender. Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst 00:44 Hi, hello, I'm Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst, a scholar of religion, Islam, race and racialization, and history. As you probably remember, we're mixing it up this season, pairing quick and dirty introductions to topics we're not experts in with interviews with folks who are experts in those very topics. M Megan Goodwin 01:01 public-scholarship-and-representation Page 1 of 23 Transcribed by https://otter.ai Today, we are giving you the skinny on public scholarship on religion, which I guess that kind of- I mean, we know more about this one than we know about the Bible. Let's start there. Anyway, public scholarship on religion, how and why to share what you know about religion with folks who maybe don't get that religion isn't done with us.