Download Syllabus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organometrallic Chemistry

CHE 425: ORGANOMETALLIC CHEMISTRY SOURCE: OPEN ACCESS FROM INTERNET; Striver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry Lecturer: Prof. O. G. Adeyemi ORGANOMETALLIC CHEMISTRY Definitions: Organometallic compounds are compounds that possess one or more metal-carbon bond. The bond must be “ionic or covalent, localized or delocalized between one or more carbon atoms of an organic group or molecule and a transition, lanthanide, actinide, or main group metal atom.” Organometallic chemistry is often described as a bridge between organic and inorganic chemistry. Organometallic compounds are very important in the chemical industry, as a number of them are used as industrial catalysts and as a route to synthesizing drugs that would not have been possible using purely organic synthetic routes. Coordinative unsaturation is a term used to describe a complex that has one or more open coordination sites where another ligand can be accommodated. Coordinative unsaturation is a very important concept in organotrasition metal chemistry. Hapticity of a ligand is the number of atoms that are directly bonded to the metal centre. Hapticity is denoted with a Greek letter η (eta) and the number of bonds a ligand has with a metal centre is indicated as a superscript, thus η1, η2, η3, ηn for hapticity 1, 2, 3, and n respectively. Bridging ligands are normally preceded by μ, with a subscript to indicate the number of metal centres it bridges, e.g. μ2–CO for a CO that bridges two metal centres. Ambidentate ligands are polydentate ligands that can coordinate to the metal centre through one or more atoms. – – – For example CN can coordinate via C or N; SCN via S or N; NO2 via N or N. -

Understanding the Invisible Hands of Sample Preparation for Cryo-EM

FOCUS | REVIEW ARTICLE FOCUS | REVIEWhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01130-6 ARTICLE Understanding the invisible hands of sample preparation for cryo-EM Giulia Weissenberger1,2,3, Rene J. M. Henderikx1,2,3 and Peter J. Peters 2 ✉ Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is rapidly becoming an attractive method in the field of structural biology. With the exploding popularity of cryo-EM, sample preparation must evolve to prevent congestion in the workflow. The dire need for improved microscopy samples has led to a diversification of methods. This Review aims to categorize and explain the principles behind various techniques in the preparation of vitrified samples for the electron microscope. Various aspects and challenges in the workflow are discussed, from sample optimization and carriers to deposition and vitrification. Reliable and versatile specimen preparation remains a challenge, and we hope to give guidelines and posit future directions for improvement. ryo-EM is providing macromolecular structures with the optimum biochemical state of the sample. Grid preparation up to atomic resolution at an unprecedented rate. In this describes the steps needed to make a sample suitable for analysis Ctechnique, electron microscopy images of biomolecules in the microscope. These steps involve chemical or plasma treat- embedded in vitreous, glass-like ice are combined to generate ment of the grid, sample deposition and vitrification. The first three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions. The detailed structural breakthroughs came about from a manual blot-and-plunge method models obtained from these reconstructions grant insight into the developed in the 1980s15 that is still being applied to achieve formi- function of macromole cules and their role in biological processes. -

18- Electron Rule. 18 Electron Rule Cont’D Recall That for MAIN GROUP Elements the Octet Rule Is Used to Predict the Formulae of Covalent Compounds

18- Electron Rule. 18 Electron Rule cont’d Recall that for MAIN GROUP elements the octet rule is used to predict the formulae of covalent compounds. Example 1. This rule assumes that the central atom in a compound will make bonds such Oxidation state of Co? [Co(NH ) ]+3 that the total number of electrons around the central atom is 8. THIS IS THE 3 6 Electron configuration of Co? MAXIMUM CAPACITY OF THE s and p orbitals. Electrons from Ligands? Electrons from Co? This rule is only valid for Total electrons? Period 2 nonmetallic elements. Example 2. Oxidation state of Fe? The 18-electron Rule is based on a similar concept. Electron configuration of Fe? [Fe(CO) ] The central TM can accommodate electrons in the s, p, and d orbitals. 5 Electrons from Ligands? Electrons from Fe? s (2) , p (6) , and d (10) = maximum of 18 Total electrons? This means that a TM can add electrons from Lewis Bases (or ligands) in What can the EAN rule tell us about [Fe(CO)5]? addition to its valence electrons to a total of 18. It can’t occur…… 20-electron complex. This is also known Effective Atomic Number (EAN) Rule Note that it only applies to metals with low oxidation states. 1 2 Sandwich Compounds Obeying EAN EAN Summary 1. Works well only for d-block metals. It does not apply to f-block Let’s draw some structures and see some new ligands. metals. 2. Works best for compounds with TMs of low ox. state. Each of these ligands is π-bonded above and below the metal center. -

Aromaticity in Polyhydride Complexes of Ru, Ir, Os, and Pt† Cite This: DOI: 10.1039/C5cp04330a Elisa Jimenez-Izala and Anastassia N

PCCP View Article Online PAPER View Journal r-Aromaticity in polyhydride complexes of Ru, Ir, Os, and Pt† Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/c5cp04330a Elisa Jimenez-Izala and Anastassia N. Alexandrova*ab Transition-metal hydrides represent a unique class of compounds, which are essential for catalysis, organic i À i À synthesis, and hydrogen storage. In this work we study IrH5(PPh3)2,(RuH5(P Pr3)2) ,(OsH5(PPr3)2) ,and À OsH4(PPhMe2)3 polyhydride complexes, inspired by the recent discovery of the s-aromatic PtZnH5 cluster À anion. The distinctive feature of these molecules is that, like in the PtZnH5 cluster, the metal is five-fold Received 23rd July 2015, coordinated in-plane, and holds additional ligands attheaxialpositions.Thisworkshowsthattheunusual Accepted 17th September 2015 coordination in these compounds indeed can be explained by s-aromaticity in the pentagonal arrangement, DOI: 10.1039/c5cp04330a stabilized by the atomic orbitals on the metal. Based on this newly elucidated bonding principle, we additionally propose a new family of polyhydrides that display a uniquely high coordination. We also report the first www.rsc.org/pccp indications of how aromaticity may impact the reactivity of these molecules. 1 Introduction many catalytic cycles, where they have either been used as catalysts or invoked as key intermediates.15,16 Aromaticity in Aromaticity is a very important concept in the contemporary general is associated with high symmetry, stability, and specific chemistry: the particular electronic structure of aromatic reactivity. Therefore, the stability of transition-metal hydride systems, where electrons are delocalized, explains their large complexes might have an important repercussion in the kinetics energetic stabilization and low reactivity. -

Representation of Three-Center−Two-Electron Bonds in Covalent Molecules with Bridging Hydrogen Atoms Gerard Parkin*

Article Cite This: J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2467−2475 pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc Representation of Three-Center−Two-Electron Bonds in Covalent Molecules with Bridging Hydrogen Atoms Gerard Parkin* Department of Chemistry, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Many compounds can be represented well in terms of the two-center−two-electron (2c−2e) bond model. However, it is well-known that this approach has limitations; for example, certain compounds require the use of three- center−two-electron (3c−2e) bonds to provide an adequate description of the bonding. Although a classic example of a compound that features a 3c−2e bond is provided by − fi diborane, B2H6,3c 2e interactions also feature prominently in transition metal chemistry, as exempli ed by bridging hydride compounds, agostic compounds, dihydrogen complexes, and hydrocarbon and silane σ-complexes. In addition to being able to identify the different types of bonds (2c−2e and 3c−2e) present in a molecule, it is essential to be able to utilize these models to evaluate the chemical reasonableness of a molecule by applying the octet and 18-electron rules; however, to do so requires determination of the electron counts of atoms in molecules. Although this is easily achieved for molecules that possess only 2c− 2e bonds, the situation is more complex for those that possess 3c−2e bonds. Therefore, this article describes a convenient approach for representing 3c−2e interactions in a manner that facilitates the electron counting procedure for such compounds. In particular, specific attention is devoted to the use of the half-arrow formalism to represent 3c−2e interactions in compounds with bridging hydrogen atoms. -

Density Functional and Molecular Orbital Studies

Reports in Theoretical Chemistry Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Relative stabilities of two difluorodiazene isomers: density functional and molecular orbital studies Jibanananda Jana Abstract: The N–N bond length in the cis isomer of difluorodiazene is shorter than that in the Department of Chemistry, Krishnagar trans isomer, giving the cis isomer higher stability. The energy partitioning approach identifies Government College, Krishnagar, the necessary and dictating parameters responsible for the higher N–N bond energy and higher Nadia, West Bengal, India non-bonded F–F interaction energy in the cis isomer. Using density functional theory, the cis isomer is found to have higher chemical hardness and lower softness, and hence, it has higher stability than the trans isomer on the basis of the principle of maximum hardness. Localized molecular orbital study shows that the cis isomer has a higher strength of delocalization of the lone pairs of electrons on the F atoms than does the trans isomer, leading to higher stability of the cis isomer. For personal use only. Keywords: cis/trans isomers, difluorodiazene, PMH, energy partitioning, localized molecular orbital, chemical hardness, softness Introduction 1 It is well known that difluorodiazine (dinitrogen difluoride), N2F2, is a gas with two isomers – cis and trans – which are shown in Figure 1. It is also known that the cis isomer predominates (∼90%) at 25°C over the trans isomer. It seems to be very obvious that the two fluorine atoms in the cis isomer, due to their greater proximity than in the trans isomer, undergo strong repulsion involving the lone pairs of electrons on the F atoms and that cis isomer is less stable than the trans one. -

A Study of the CIS Effect of Some Phosphorus Donor Ligands

A STUDY OF THE CIS EFFECT OF SOME PHOSPHORUS DONOR LIGANDS Karen L. Chalk B.Sc. (Hons., Chem.), Queen's University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE RFQTJIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Chemistry @ Karen L. Chalk, 1981 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 1981 All riqhts reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author APPROVAL Name : Karen L. Chalk Deqree : Master of Science Title of Research Pro3ect: A Study of the -Cis-Effect of Some Phosphorus Liaands Supervisory Committee: - --Senior ~upervid?: R.K. Pomeroy a Assistant Professor D. Sutton Professor - T.N. Bell Professor K. E. Newman Internal Examiner Date Approved : no^* 26: iq81 ii PART l AL COPYR l GHT L l CENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay "A Study of the Cis-Effect of Some Phosphorus Donor Linands" Author: (signature) Karen L. -

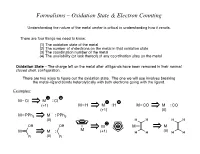

Oxidation State & Electron Counting

Formalisms – Oxidation State & Electron Counting Understanding the nature of the metal center is critical in understanding how it reacts. There are four things we need to know: (1) The oxidation state of the metal (2) The number of d electrons on the metal in that oxidation state (3) The coordination number of the metal (4) The availability (or lack thereof) of any coordination sites on the metal Oxidation State – The charge left on the metal after all ligands have been removed in their normal, closed shell, configuration. There are two ways to figure out the oxidation state. The one we will use involves breaking the metal–ligand bonds heterolytically with both electrons going with the ligand. Examples: M Cl M Cl (+1) M H M H M CO M CO (+1) (0) M PPh3 M PPh3 (0) H H H H OR OR M M M M M M (+1) H H (0) H H R (0) R Formalisms – Oxidation State & Electron Counting Now that we know the oxidation state of the metal we can figure out the d-electron count. This can be done easily by consulting the periodic table. The 4s and 3d orbitals are very close in energy and for complexes of transition metals it is a good approximation that the d orbitals are filled first. Group # 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 First row 3d Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Second row 4d Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Third row 5d Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt Au 0 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 – I 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 oxidation state II 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 III 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 IV 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 # of d-electrons Formalisms – Oxidation State & Electron Counting Why is knowing the number of d-electrons important? 18 electron rule – In mononuclear diamagnetic complexes, the toal number of electrons in the bonding shell (the sum of the metal d electrons plus those contributed by the ligands) never exceeds 18. -

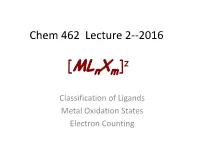

Lecture 2--2016

Chem 462 Lecture 2--2016 z [MLnXm] Classification of Ligands Metal Oxidation States Electron Counting Overview of Transition Metal Complexes 1.The coordinate covalent or dative bond applies in L:M 2.Lewis bases are called LIGANDS—all serve as σ-donors some are π-donors as well, and some are π-acceptors 3. Specific coordination number and geometries depend on metal and number of d-electrons 4. HSAB theory useful z [MLnXm] a) Hard bases stabilize high oxidation states b) Soft bases stabilize low oxidation states Classification of Ligands: The L, X, Z Approach Malcolm Green : The CBC Method (or Covalent Bond Classification) used extensively in organometallic chemistry. L ligands are derived from charge-neutral precursors: NH3, amines, N-heterocycles such as pyridine, PR3, CO, alkenes etc. X ligands are derived from anionic precursors: halides, hydroxide, alkoxide alkyls—species that are one-electron neutral ligands, but two electron 4- donors as anionic ligands. EDTA is classified as an L2X4 ligand, features four anions and two neutral donor sites. C5H5 is classified an L2X ligand. Z ligands are RARE. They accept two electrons from the metal center. They donate none. The “ligand” is a Lewis Acid that accepts electrons rather than the Lewis Bases of the X and L ligands that donate electrons. Here, z = charge on the complex unit. z [MLnXm] octahedral Square pyramidal Trigonal bi- pyramidal Tetrahedral Range of Oxidation States in 3d Transition Metals Summary: Classification of Ligands, II: type of donor orbitals involved: σ; σ + π; σ + π*; π+ π* Ligands, Classification I, continued Electron Counting and the famous Sidgewick epiphany Two methods: 1) Neutral ligand (no ligand carries a charge—therefore X ligands are one electron donors, L ligands are 2 electron donors.) 2) Both L and X are 2-electron donor ligand (ionic method) Applying the Ionic or 2-electron donor method: Oxidative addition of H2 to chloro carbonyl bis triphenylphosphine Iridium(I) yields Chloro-dihydrido-carbonyl bis-triphenylphosphine Iridium(III). -

Metal-Ligand Bonding and Inorganic Reaction Mechanisms Year 2

Metal-Ligand Bonding and Inorganic Reaction Mechanisms Year 2 RED Metal-ligand and metal-metal bonding of the transition metal elements Synopsis Lecture 1: Trends of the transition metal series. Ionic vs Covalent bonding. Nomenclature. Electron counting. Lecture 2: Thermodynamics of complex formation. Why complexes form. Recap of molecular orbital theory. 18-electron rule. Lecture 3: Ligand classes. -donor complexes. Octahedral ML6 molecular orbital energy diagram. Lecture 3: - acceptor ligands and synergic bonding. Binding of CO, CN , N2, O2 and NO. Lecture 4: Alkenes, M(H2) vs M(H)2, Mn(O2) complexes, PR3. Lecture 5: 2- - 2- 3- donor ligands, metal-ligand multiple bonds, O , R2N , RN , N . Lecture 6: ML6 molecular orbital energy diagrams incorporating acceptor and donor ligands. Electron counting revisited and link to spectrochemical series. Lecture 7: Kinetics of complex formation. Substitution mechanisms of inorganic complexes. Isomerisation. Lecture 8: Ligand effects on substitution rates (trans-effect, trans-influence). Metal and geometry effects on substitution rates. Lecture 9: Outer sphere electron transfer. Lecture 10: Inner Sphere electron transfer. Bridging ligands. 2 Learning Objectives: by the end of the course you should be able to i) Use common nomenclature in transition metal chemistry. ii) Count valence electrons and determine metal oxidation state in transition metal complexes. iii) Understand the physical basis of the 18-electron rule. iv) Appreciate the synergic nature of bonding in metal carbonyl complexes. v) Understand the relationship between CO, the 'classic' -acceptor and related ligands such as NO, CN, N2, and alkenes. 2 vi) Describe the nature of the interaction between -bound diatomic molecules (H2, O2) and their relationship to -acceptor ligands. -

Symmetry 2010, 2, 1745-1762; Doi:10.3390/Sym2041745 OPEN ACCESS Symmetry ISSN 2073-8994

Symmetry 2010, 2, 1745-1762; doi:10.3390/sym2041745 OPEN ACCESS symmetry ISSN 2073-8994 www.mdpi.com/journal/symmetry Review n– Polyanionic Hexagons: X6 (X = Si, Ge) Masae Takahashi Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University, 2-1-1 Katahira, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8577, Japan; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-22-795-4271; Fax: +81-22-795-7810 Received: 16 August 2010; in revised form: 7 September 2010 / Accepted: 27 September 2010 / Published: 30 September 2010 Abstract: The paper reviews the polyanionic hexagons of silicon and germanium, focusing on aromaticity. The chair-like structures of hexasila- and hexagermabenzene are similar to a nonaromatic cyclohexane (CH2)6 and dissimilar to aromatic D6h-symmetric benzene (CH)6, although silicon and germanium are in the same group of the periodic table as carbon. Recently, six-membered silicon and germanium rings with extra electrons instead of conventional substituents, such as alkyl, aryl, etc., were calculated by us to have D6h symmetry and to be aromatic. We summarize here our main findings and the background needed to reach them, and propose a synthetically accessible molecule. Keywords: aromaticity; density-functional-theory calculations; Wade’s rule; Zintl phases; silicon clusters; germanium clusters 1. Introduction This review treats the subject of hexagonal silicon and germanium clusters, paying attention to the two-dimensional aromaticity. The concept of aromaticity is one of the most fascinating problems in chemistry [1,2]. Benzene is the archetypical aromatic hexagon of carbon: it is a planar, cyclic, fully conjugated system that possesses delocalized electrons. The two-dimensional aromaticity of planar monocyclic systems is governed by Hückel’s 4N + 2 rule, where N is the number of electrons. -

The 18 Electron Guideline: a Primmer This Can Be Given to Students to Read

Created by Burke Scott Williams ([email protected]) and posted on VIPEr on 01/10/2009. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike License in 2009. To view a copy of this license visit http://creativecommons.org/about/license/ The 18 Electron Guideline: A Primmer This can be given to students to read The 18 electron “rule” is a very useful tool for predicting which complexes will behave as “closed shell” or “saturated” species. Generally speaking, transition metal compounds with more or fewer than 18 valence electrons will be less stable than close analogs that do have 18 electrons. The 18 electron “rule” (s orbital, 3 p-orbitals, 5 d-orbitals, 2 e- in each) ( is a close analog to the “octet rule” (1 s orbital, 3 p-orbitals, 2 e- in each) in general and organic chemistry, but the much larger number of exceptions in transition metal chemistry is such that it’s really more of a “guideline” than a “rule”. But how do we learn to count to 18? There are two primary methods (somewhat analogous to the “oxidation state/ionic model” and the “formal charge/covalent model” in general chemistry. In these more traditional models, we can count the electrons around carbon in CO2 in one of two ways: Oxidation State method: 1. Remove “ligands” (oxygen) as closed shell (full octet) species, and assign oxidation states to the resultant cations and anions: C4+ + 2 O2- 2. Now bring the “ligands” back in. Each bond is worth two electrons (4 for double bonds, 6 for triple) 2 double bonds = 8 electrons, carbon is an “8 electron species” Formal Charge method: 1.