Regional Production, Distribution, and Utilization of Instructional Television Programs: a Critical Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside This Month

JULY 2015 INSIDE THIS MONTH 217-726-6600 • [email protected] www.springfieldbusinessjournal.com Happy Sushi p. 4 PJP Autos p. 6 By Michelle Higginbotham, associate publisher Springfield Business Journal has been recognizing outstanding KEYNOTE SPEAKER young professionals in Springfield and the surrounding MAYOR JAMES O. LANGFELDER Calvin Pitts p. 11 communities since 1997, making Forty Under 40 our longest standing awards program. That means our list A lifelong resident of Springfield, Prior to becoming a public servant, of previous recipients has many Jim Langfelder took office as mayor Mayor Langfelder worked in banking familiar names, including Mayor Jim Langfelder, this on May 7, 2015. Mayor Langfelder for 14 years and specialized in product year’s keynote speaker. The recipients represent a has charge over operations of the and business development. He holds wide variety of local businesses and industries, but City of Springfield including the a Bachelors of Arts degree from all contribute to their communities through both their departments of Community Relations; University of Illinois Springfield and professional lives and volunteer service. Communications; Convention an Associates degree from Lincoln The individuals profiled in this issue were all and Visitors Bureau; Corporation Land Community College, where his selected from nominations made by our readers. Counsel; CWLP; Planning & Economic main course of studies was business While some received multiple nominations, Development; Human Resources; management. the selection process is not based on the sheer Library; Budget and Management, Mayor Langfelder has long been number of votes, but rather the individual’s overall All in the family p. 14 Police and Fire; and Public Works. -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices

25528 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Closing Date, published in the Federal also purchase 74 compressed digital Register on February 22, 1996.3 receivers to receive the digital satellite National Telecommunications and Applications Received: In all, 251 service. Information Administration applications were received from 47 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, AL (Alabama) [Docket Number: 960205021±6132±02] the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, File No. 96006 CTB Alabama ETV RIN 0660±ZA01 American Samoa, and the Commission, 2112 11th Avenue South, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Ste 400, Birmingham, AL 35205±2884. Public Telecommunications Facilities Islands. The total amount of funds Signed By: Ms. Judy Stone, APT Program (PTFP) requested by the applications is $54.9 Executive Director. Funds Requested: $186,878. Total Project Cost: $373,756. AGENCY: National Telecommunications million. Notice is hereby given that the PTFP Replace fourteen Alabama Public and Information Administration, received applications from the following Television microwave equipment Commerce. organizations. The list includes all shelters throughout the state network, ACTION: Notice, funding availability and applications received. Identification of add a shelter and wiring for an applications received. any application only indicates its emergency generator at WCIQ which receipt. It does not indicate that it has experiences AC power outages, and SUMMARY: The National been accepted for review, has been replace the network's on-line editing Telecommunications and Information determined to be eligible for funding, or system at its only production facility in Administration (NTIA) previously that an application will receive an Montgomery, Alabama. announced the solicitation of grant award. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

E82 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks January 20, 2015 always remember and honor. While we con- DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SE- never dies.’’ Captain Timley is one such great tinue to mourn their loss we should, to para- CURITY APPROPRIATIONS ACT, soul, who served humanity in a special way. phrase General George Patton: ‘‘Thank God 2015 Each day he graced the people around him that such people ever lived.’’ with an enthusiastic sincerity of presence. His SPEECH OF impression on this earth extends beyond him- Two years after his death, Victor Lovelady HON. PAUL RYAN self to the very wellbeing of the Macon com- may not be a household name, but there is no munity, and for it he will be remembered by doubt that he is an American hero. He worked OF WISCONSIN IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the community for time to come. hard to provide an honest living and when in On a personal note, my staff and I will al- danger, thought first to protect others instead Tuesday, January 13, 2015 ways remember and cherish the times Captain of himself. When people hear Victor’s story The House in Committee of the Whole Timley would poke his head into our Macon today, they are inspired because of his acts of House on the state of the Union had under District Office to check on us just to see how bravery, conviction, and compassion—in other consideration the bill (H.R. 240) making ap- we were doing and offer his help. propriations for the Department of Home- Captain Timley is survived by his wife, words, to act as a true American. -

KUAC World Fairbanks Fairbanks AK Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM

Full Name Market City State Day Start Date Time (local) WORLD in ET KUAC World Fairbanks Fairbanks AK Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * APT HDTV Birmingham Birmingham AL Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * APT World Mobile-Pensacola Mobile AL Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * APT World Huntsville-Decatur Florence AL Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * APT World Montgomery (Selma) Montgomery AL Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * AETN Plus Little Rock, AR Mountain Vie AR Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * AETN Plus Ft. Smith, AR Fayetteville AR Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * AETN Plus Monroe-El Dorado El Dorado AR Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * AETN Plus Jonesboro Jonesboro AR Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * KAET World Phoenix Phoenix AZ Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * KUAS World Tucson Tucson AZ Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * KCET HDTV Los Angeles Los Angeles CA Frid 2-Oct 9:00PM KLCS-DT Los Angeles Los Angeles CA Sun 18-Oct 7:00PM PBS SoCal Plus Los Angeles Huntington B CA Sun 11-Oct 11:00PM PBS SoCal World Los Angeles Huntington B CA Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * KVCR HDTV Los Angeles San Bernardin CA Frid 15-Oct 8:00PM KQED World San Francisco San Francisco CA Tues/Wed/Tues/Tue Oct 10/11/20/20 2PM/10PM/2AM/ 8AM Local Time KRCB HDTV San Francisco Cotati CA KVIEDT World Sacramento Sacramento CA Tues/Wed/Tues Oct 13/14/20 9PM/1AM/12PM/5AM & * KVPT HDTV Fresno-Visalia -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

Great Plains National Instructional Television Library the POLICY BOARD of the Greatplains National Instructional Television Library

REPOR T RESUMES ED 019 007 EM 006 677 THE 1968 CATALOG OF RECORDED TELEVISION COURSES AVAILABLE FROM NATIONAL GREAT PLAINS INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION LIBRARY. NEBRASKA UNIV., LINCON EDRS PRICE MF -$0.50 HC -$4.64 114P. DESCRIPTORS- *INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION, *TELECOURSES, *TELEVISED INSTRUCION, AUDIOVISUAL AIDS, EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION, *CATALOGS SECONDARY EDUCATION, ELEMENTARY EDUCATION, HIGHEREDUCATION, PARENT EDUCATION, ADULT EDUCATION, ENRICHRENT ACTIVITIES, INTENDED FOR USE BY ADMINISTRATORS AND PLANNERS, THIS GUIDE DESCRIBES COURSES AVAILABLE FROM THE GREAT PLAINS ITV LIBRARY. FIVE INDICES ARE INCLUDED, ONE CLASSIFYING ELEMENTARY, JUNIOR HIGH, SECONDARY AND ADULT COURSES BY SUBJECT, ANOTHER LISTS THEM BY GRADE LEVEL. A THIRD LISTS COLLEGE COURSES BY SUBJECT, ANOTHER DESCRIBES INSERVICE TEACHER - TRAINING MATERIALS. A FINAL. ALPHABETIZED INDEX LISTS ALL COURSES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE FROM THE GREAT PLAINS LIBRARY INCLUDING FORD FOUNDATION KINESCOPES. LEASING AND PURCHASING COSTS ARE GIVEN, AS WELL AS PREVIEWING POLICIES AND ORDERING INFORMATION. (JM) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. 1`, s0 SES ELEMENTARY SECONDARY COLLEGE Great Plains National Instructional Television Library THE POLICY BOARD of the GreatPlains National Instructional Television Library Though television is a relative youngster in the field of education, its usefulness in schools and colleges has become evident in thousands of classrooms across the United States. Educational institutions employing instruction by television have found recorded telecourses from Great Plains National Instructional Television Library playing a significant role in their curricular planning. -

List of Directv Channels (United States)

List of DirecTV channels (United States) Below is a numerical representation of the current DirecTV national channel lineup in the United States. Some channels have both east and west feeds, airing the same programming with a three-hour delay on the latter feed, creating a backup for those who missed their shows. The three-hour delay also represents the time zone difference between Eastern (UTC -5/-4) and Pacific (UTC -8/-7). All channels are the East Coast feed if not specified. High definition Most high-definition (HDTV) and foreign-language channels may require a certain satellite dish or set-top box. Additionally, the same channel number is listed for both the standard-definition (SD) channel and the high-definition (HD) channel, such as 202 for both CNN and CNN HD. DirecTV HD receivers can tune to each channel separately. This is required since programming may be different on the SD and HD versions of the channels; while at times the programming may be simulcast with the same programming on both SD and HD channels. Part time regional sports networks and out of market sports packages will be listed as ###-1. Older MPEG-2 HD receivers will no longer receive the HD programming. Special channels In addition to the channels listed below, DirecTV occasionally uses temporary channels for various purposes, such as emergency updates (e.g. Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike information in September 2008, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011), and news of legislation that could affect subscribers. The News Mix channels (102 and 352) have special versions during special events such as the 2008 United States Presidential Election night coverage and during the Inauguration of Barack Obama. -

WSIU, WUSI, WSEC, WMEC & WQEC DT3 (SD2) CREATE Programming

WSIU, WUSI, WSEC, WMEC & WQEC DT3 (SD2) CREATE Programming Schedule for July, 2020 as of 06/15/20 Wednesday, July 1, 2020 12am 100 Days, Drinks, Dishes and Destinations. CC #205 In the culinary adventure series 100 DAYS, DRINKS, DISHES & DESTINATIONS, Emmy and James Beard Award-winning wine expert Leslie Sbrocco travels the world with glass and fork in hand, indulging in delicacies, uncovering local hangouts, meeting talented artisans and visiting both up-and-coming and acclaimed restaurants, wineries and breweries. This season, Leslie explores San Francisco's Chinatown and Calistoga, California before jetting off to Vienna, Austria; Budapest, Hungary; and Normandy, France. TVG 12:30 Nick Stellino: Storyteller in the Kitchen. CC #203 The Vegetarian. While pondering life as a vegetarian, Nick discovers some fabulous new dishes loaded with spectacular flavors. Dishes include: Chilled Cantaloupe Soup / Salmon with Spinach and Pancetta Cream Sauce / Biancomangiare (Sicilian Almond Pudding). TVG 1am Moveable Feast with Fine Cooking. CC #705 Beachside In Brighton. We are in Brighton, a beautiful English seaside resort town, in this episode of Moveable Feast with Fine Cooking. Host Alex Thomopoulos is here to cook a feast with acclaimed chefs Michael Bremner and Sam Lambert. To gather the freshest fish, the chefs head to Brighton & Newhaven Fish Sales, where fisherman deliver the daily catch straight from the sea, then to inland to Namayasai, a gem of a farm that grows an exquisite array of Japanese vegetables. And finally, they travel to Saddlescombe Farm & Newtimber Hill, where sheep graze in the scenic British countryside. Back at Chef Michael's waterfront restaurant, Murmur, the trio cooks a delectable feast with the daily catch and an Herby White Wine Butter Sauce, Fire-Roasted Lamb, and Shrimp Shu Mai. -

FCC-21-98A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 21-98 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Assessment and Collection of Regulatory Fees for ) MD Docket No. 21-190 Fiscal Year 2021 ) ) REPORT AND ORDER AND NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Adopted: August 25, 2021 Released: August 26, 2021 Comment Date: [30 days after date of publication in the Federal Register] Reply Comment Date: [45 days after date of publication in the Federal Register] By the Commission: Acting Chairwoman Rosenworcel and Commissioners Carr and Simington issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND.....................................................................................................................................2 III. REPORT AND ORDER..........................................................................................................................6 A. Allocating Full-time Equivalents......................................................................................................7 B. Commercial Mobile Radio Service Regulatory Fees Calculation ..................................................27 C. Direct Broadcast Satellite Fees .......................................................................................................28 D. Full-Service Television Broadcaster Fees ......................................................................................36 -

Local Value 2014 Key Services Local Impact

Peoria n Bloomington n Galesburg Public Media for Central Illinois 2014 LOCAL CONTENT AND SERVICE “PBS and local public television continues to be a last bastion of culture and quality.” REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY - Samuel DePino Chatsworth, IL WTVP enriches Central Illinois as a necessary source for educational, scientific, entertainment, and cultural content that connects our community on a local and world level. LOCAL 2014 KEY LOCAL VALUE SERVICES IMPACT WTVP is a valuable part of In 2014, WTVP provided these WTVP’s local services have Central Illinois. key local services deep impact in Central Illinois. We teach letters and numbers • Downstate Gubernatorial WTVP provided 1,523 free with unsupassed programming Debate and Republican books to local children. for children. We fuel life-long Primary Debate learning with programs that • Coverage of Illinois legislative WTVP hosted 15 community engage minds of all ages. We activities on Illinois Lawmakers events, actively engaging view- inform the citizenry with in- • Access to local, state and ers with our content. depth, balanced information. national political leaders We open hearts through the through At Issue WTVP produced the only tele- best in drama, arts and enter- • Literacy initiatives such as vised downstate debate of the tainment. We care for our com- the PBS KIDS Writers 2014 Gubernatorial election, munity through information and Contest and Video Book broadcasting it statewide on activities. Reports Illinois public media outlets and • Educational support through beyond. WTVP-Public Media advances PBS LearningMedia training life in Central Illinois by deliv- events and online resources WTVP aired 25,632 hours of ering engaging, inspiring and • New documentary following quality programming on three entertaining content. -

PBS Broadcast Schedule 10-6-14

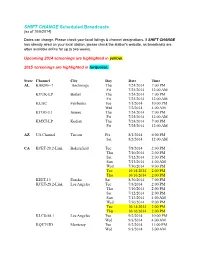

SHIFT CHANGE Scheduled Broadcasts [as of 10/6/2014] Dates can change. Please check your local listings & channel designations. If SHIFT CHANGE has already aired on your local station, please check the station's website, as broadcasts are often available online for up to two weeks. Upcoming 2014 screenings are highlighted in yellow. 2015 screenings are highlighted in turquoise. State Channel City Day Date Time AL KAKM+-7 Anchorage Thu 7/24/2014 7:00 PM Fri 7/25/2014 12:00 AM KYUK-LP Bethel Thu 7/24/2014 7:00 PM Fri 7/25/2014 12:00 AM KUAC Fairbanks Tue 7/1/2014 10:00 PM Wed 7/2/2014 4:00 AM KTOO-3.1 Juneau Thu 7/24/2014 7:00 PM Fri 7/25/2014 12:00 AM KMXT-LP Kodiak Thu 7/24/2014 7:00 PM Fri 7/25/2014 12:00 AM AZ UA Channel Tucson Fri 8/1/2014 6:00 PM Sat 8/2/2014 12:00 AM CA KCET-28.2-Link Bakersfield Tue 7/8/2014 2:00 PM Thu 7/10/2014 2:00 PM Sat 7/12/2014 2:00 PM Sun 7/13/2014 4:00 AM Wed 7/30/2014 9:00 PM Tue 10/14/2014 2:00 PM Thu 10/16/2014 2:00 PM KEET-13 Eureka Sat 8/30/2014 7:00 PM KCET-28.2-Link Los Angeles Tue 7/8/2014 2:00 PM Thu 7/10/2014 2:00 PM Sat 7/12/2014 2:00 PM Sun 7/13/2014 4:00 AM Wed 7/30/2014 9:00 PM Tue 10/14/2014 2:00 PM Thu 10/16/2014 2:00 PM KLCS-58.1 Los Angeles Tue 9/2/2014 10:00 PM Wed 9/3/2014 4:00 AM KQET-HD Monterey Tue 9/2/2014 11:00 PM Wed 9/3/2014 5:00 AM KVCR-24.3 DC Palm Desert Thu 8/7/2014 10:00 PM Fri 8/8/2014 3:00 AM Sun 8/10/2014 10:00 PM KRCB-22.1 Rohnert Park Tue 9/2/2014 9:00 PM KVIE-.2 Sacramento Sat 7/12/2014 11:00 PM KQED-9 SD San Francisco Tue 9/2/2014 11:00 PM Wed 9/3/2014 5:00 AM KQED-9 -

MF01/N06 Plus Postage

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 292 440 IR 013 191 TITLE A Report to the People. 20Years of Your National Commitment to Public Broadcasting, 1967-1987. 1986 Annual Report. INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-89776-100-6 PUB DATE [15 May 87] NOTE 129p.; Photographs will not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/n06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annual Reports; Cultural Enrichment; Educational Radio; *Educational Television; *Financial Support; *Programing (Broadcast); *Public Television; *Television Viewing IDENTIFIERS *Annenberg CPB Project; *Corporation for Public Broadcasting ABSTRACT This annual report for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) for fiscal year 1986 also summarizes the CPB's activities over the last 20 years. The front inside cover folds out to three pages and provides a chronology of the important events in CPB history from its inception in 1967 to 1987. A narrative report on the CPB's 20 years of operation highlights its beginnings, milestones, programming, and audiences; the broadcasting system; and funding. Comments in support of public television by a wide variety of public figures concludes this portion of the report. The 1986 annual report provides information on television programming, radio programming, community outreach, adult learning, program support activities, and system support activities for that fiscal year. The CPB Board of Directors and officers are also listed, and a financial accounting by the firm of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co. is provided. The text is supplemented by a number of graphs, figures, and photographs. (EW) ********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document.