10. Uses and Abuses of Refugee Histories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don't Blame the Unemployed

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 150, part 1, 2017, pp. 3–8. ISSN 0035-9173/17/010003-06 Don’t Blame the Unemployed Peter Baume AC DistFRSN Distinguished Fellow’s Lecture Annual Dinner of the Royal Society of New South Wales, The Union, University and Schools Club 25 Bent St, Sydney, 3 May, 2017 Professor Baume studied medicine at the University of Sydney, General Hospital, Birmingham, and as a U.S. Public Health Service Fellow in Nashville, Tennessee. He practiced as a gastroenterologist and physician in Australia from 1967 to 1974 and received his M.D. from the University of Sydney during that time. From 1974 to 1991 he served as a Senator for New South Wales. He held a number of portfolios, including Aboriginal Affairs, Health, and Education, and was a member of Cabinet. From 1991 to 2000, Professor Baume was Professor of Community Medicine at the University of N.S.W. He was on the Council of the Australian National University from 1986 to 2006 and was Chancellor of A.N.U. from 1994 to 2006. He has also been Commissioner of the Australian Law Reform Commission, Deputy Chair of the Australian National Council on AIDS, and Foundation Chair of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority. id you know that the good food you photography? You are thoughtful and dis- Dhave just eaten demands a quarter of all tinguished and contributing to society. your blood for digestion and absorption, and Let me put one — just one — serious this can lead to anyone becoming somno- proposition to you to start. -

Report X Terminology Xi Acknowledgments Xii

Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee Consideration of Legislation Referred to the Committee Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 March 1997 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee Consideration of Legislation Referred to the Committee Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 March 1997 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1326-9364 This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee, and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Legislation Committee Members Senator E Abetz, Tasmania, Chair (Chair from 3 March 1997) Senator J McKiernan, Western Australia, Deputy Chair Senator the Hon N Bolkus, South Australia Senator H Coonan, New South Wales (from 26 February 1997: previously a Participating Member) Senator V Bourne, New South Wales (to 3 March 1997) Senator A Murray, Western Australia (from 3 March 1997) Senator W O’Chee, Queensland Participating Members All members of the Opposition: and Senator B Brown, Tasmania Senator M Colston, Queensland Senator the Hon C Ellison, Western Australia (from 26 February 1997: previously the Chair) Senator J Ferris, South Australia Senator B Harradine, Tasmania Senator W Heffernan, New South Wales Senator D Margetts, Western Australia Senator J McGauran, Victoria Senator the Hon N Minchin, South Australia Senator the Hon G Tambling, Northern Territory Senator J Woodley, Queensland Secretariat Mr Neil Bessell (Secretary -

July 2009 VES NSW Newsletter

You will be asked to vote on the adoption of the new name at the next General Meeting of the society on August 9th 2009. Proxy forms are enclosed with this newsletter if you would like to vote and cannot attend the meeting. is in calling for volunteers, say for the Olympics. Calling for volunteers for VE is NOT appropriate. • We need to align our discussions of dying within the context of a continuum that includes palliative care and end-of-life choice. There can be many steps in a person’s process of dying. • There should be a nexus in the public’s mind between palliative, end-of-life care and physician-assisted dying. • It is important to our members and supporters to provide information to encourage people to have conversations with their doctors about their end-of-life healthcare decisions and to promote of the use of reliable Dear members advance health care directives, so that fewer families Your committee has voted to recommend a change of name to and healthcare providers will have to struggle with making difficult decisions in the absence of guidance from the patient. DYING WITH DIGNITY NSW • The new name will encourage discussion about a practice This new name will be voted on at the next General Meeting. that is happening covertly. We propose that physician-assisted dying become a legally accepted and protected element in medical As many of you are aware, VESnsw has had lengthy and in-depth practice—an option for patients who want it and ask for it and for discussions over many years about the pros and cons of such a doctors who are sympathetic and wish to participate, with a process move. -

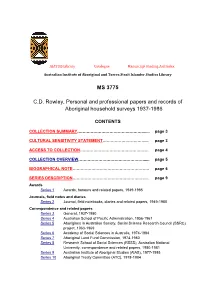

MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and Professional Papers and Records Of

AIATSIS Library Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys 1937-1986 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY……………………………….…………...... page 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT…………………………..... page 3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION…………………………………………… page 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW…………………………….……………..... page 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………………………… page 6 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………... page 9 Awards Series 1 Awards, honours and related papers, 1949-1985 Journals, field notes and diaries Series 2 Journal, field notebooks, diaries and related papers, 1949-1980 Correspondence and related papers Series 3 General, 1937-1980 Series 4 Australian School of Pacific Administration, 1956-1961 Series 5 Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council (SSRC) project, 1963-1969 Series 6 Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, 1974-1984 Series 7 Aboriginal Land Fund Commission, 1974-1980 Series 8 Research School of Social Sciences (RSSS), Australian National University, correspondence and related papers, 1980-1981 Series 9 Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS), 1977-1985 Series 10 Aboriginal Treaty Committee (ATC), 1978-1984 MS 3775: C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys, 1937-1986 Series 11 Sundry, 1965-1981 Research project files Series 12 UNESCO Mission on Adult & Workers’ Education to S-E Asia, 1954-55 Series 13 Aborigines in -

Australians Take Sides on the Right to Die

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship THE LAST RIGHT? AUSTRALIANS TAKE SIDES ON THE RIGHT TO DIE Simon Chapman Stephen Leeder (eds.) Originally published by Mandarin Books Port Melbourne, Victoria 1995 ISBN 1 86330 504 1 Now out of print Feel free to distribute, copy or reproduce any part of this book with acknowledgement to the editors. Simon Chapman is professor of public health at the University of Sydney [email protected] 1 Feb 2010 1 Index of contributors Sir GUSTAV NOSSAL Sir MARK OPILPHANT PHILLIP ADAMS DAVID PENINGTON EUGENE AHERN RONALD PENNY YVONNE ALLEN RAYMOND APPLE PETER BAUME MARSHALL PERRON CHARLES BIRCH CHRIS PUPLICK VERONICA BRADY MARK ROSENTHAL JOHN BUCHANAN BRUCE RUXTON JIM CAIRNS B.A. SANTAMARIA DENISE CAMERON DOROTHY SIMONS JOHN CARGHER PETER SINGER MIKE CARLTON Sir NINIAN STEPHEN MICHAEL CARR‐GREGG LOUISE SYLVAN TRICIA CASWELL BARBARA THIERING SIMON CHAPMAN BERNADETTE TOBIN EDWARD CLANCY IAN WEBSTER EVA COX ROBYN WILLIAMS LORRAINE DENNERSTEIN ROGER WOODRUFF ANNE DEVESON MICHAEL WOOLDRIDGE MARCUS EINFELD JULIA FREEBURY MORRIS GLEITZMAN HARRY GOODHEW NIGEL GRAY KATE GRENVILLE BLL HAYDEN GERARD HENDERSON HARRY HERBERT JOHN HINDE ELIZABETH JOLLEY ALAN JONES MICHAEL KIRBY HELGA KUHSE TERRY LANE MICHAEL LEUNIG NORELLE LICKISS MILES LITTLE ROBERT MARR JIM McCLELLAND COLLEEN McCULLOUGH JIM McCLELLAND PADRAIC P. McGUINNESS GEORGE NEGUS BRENDAN NELSON FRED NILE 2 Going To Sleep Now the day has wearied me. And my ardent longing shall the stormy night in friendship enfold me like a tired child Hands, leave all work; brow, forget all thought. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

9. Legislation As a Contemporary Public Health Tool

Progress Through Partnerships Highlights of Public Health Activities in Australia Highlights of Public Health Activities in Australia Progress Through Partnerships Through Progress i © Copyright: National Public Health Partnership This work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and provided no commercial usage or sale is to be made. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires the written permission of the National Public Health Partnership, GPO Box 1670N, Melbourne 3001, Victoria, Australia. The NPHP Secretariat would like to acknowledge and thank the many individuals who contributed to the compilation of this report, including all those involved in the NPHP work program, staff from the Commonwealth Population Health Division and the numerous program areas within state and territory health authorities that provided material for Part III of the report. ISBN Number 0 7311 7602 2 Further copies: Contact the National Public Health Partnership Secretariat, 120 Spencer Street, Melbourne 3001, Victoria, Australia. Telephone: (61 3) 9637 5512 Facsimile: (61 3) 9637 5510 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dhs.vic.gov.au/nphp ii Preface This 1998–99 Annual Report of the National Public Health Partnership is the first comprehensive report on our work. It highlights the Partnership’s progress in addressing its main shared priorities and in developing a comprehensive coordinated national public health effort. This national effort is complemented by the public health activity undertaken in all jurisdictions that make up the Partnership, and the report provides a snapshot of just some of the huge range. -

National Asset: 50 Years of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre~ANU Press

A NATIONAL ASSET 50 YEARS OF THE STRATEGIC AND DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE A NATIONAL ASSET 50 YEARS OF THE STRATEGIC AND DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE EDITED BY DESMOND BALL AND ANDREW CARR Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A national asset : 50 years of the Strategic & Defence Studies Centre (SDSC) / editors: Desmond Ball, Andrew Carr. ISBN: 9781760460563 (paperback) 9781760460570 (ebook) Subjects: Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre--History. Military research--Australia--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Ball, Desmond, 1947- editor. Carr, Andrew, editor. Dewey Number: 355.070994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents About the Book . vii Contributors . ix Foreword: From 1966 to a Different Lens on Peacemaking . xi Preface . xv Acronyms and Abbreviations . xix List of Plates . xxi 1 . Strategic Thought and Security Preoccupations in Australia . 1 Coral Bell 2 . Strategic Studies in a Changing World . 17 T.B. Millar 3 . Strategic Studies in Australia . 39 J.D.B. Miller 4 . From Childhood to Maturity: The SDSC, 1972–82 . 49 Robert O’Neill 5 . Reflections on the SDSC’s Middle Decades . 73 Desmond Ball 6 . SDSC in the Nineties: A Difficult Transition . 101 Paul Dibb 7 . -

SENATE Official Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard TUESDAY, 21 MAY 1996 THIRTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CANBERRA CONTENTS TUESDAY, 21 MAY Questions Without Notice— Export Market Development Grants ........................ 773 Sale of Telstra ....................................... 774 Higher Education ..................................... 776 National Reconciliation Week ............................ 777 Migrants: Social Welfare Entitlements ...................... 777 Commonwealth Ombudsman ............................. 778 Higher Education ..................................... 779 Logging and Woodchipping .............................. 780 Superannuation ...................................... 781 Women Parliamentarians ................................ 782 Native Title ......................................... 783 Social Security Recipients ............................... 784 Superannuation ...................................... 785 Self-funded Retirees ................................... 786 Migrants: Social Welfare Entitlements ...................... 787 Sale of Telstra ....................................... 787 Petitions— French Nuclear Testing ................................. 793 Afghanistan ......................................... 793 Religion and Democracy in Australia ....................... 794 Notices of Motion— Condolences: Mr Michael Lloyd .......................... 794 Student Newspapers ................................... 794 Public Service: Office Closures -

Annual Report 2008-09

Annual Report 2008-09 ABN 27 109 607 472 Vision, Mission & Values Our Vision A society that is committed to the prevention of dementia, and that values and supports people living with dementia. Our Mission To minimise the incidence and impact of dementia through leadership, innovation and partnerships - in advocacy, policy, education, services and research. Our Values Respect for the dignity of all individuals Cooperative working relationships Integrity, accountability, transparency Value the contribution of all people involved with our work Strength through unity, with respect for diversity Responsiveness to our community The Australian Government funded programs of Alzheimer’s Australia NSW are: National Dementia Support Program which includes early intervention or Living with Memory Loss, National Dementia Helpline and Referral Service, Education and Awareness, Dementia Memory Community Centres - at North Ryde, Bega and Port Macquarie, Regional Partnerships which includes part funding of the library and some education services. The Australian Government has also funded a Remote Access Dementia Education Program and the Bega Mobile Respite Team and the CCRC. 2 Alzheimer’s Australia NSW All of these people live with dementia Contents Report from the Chairman 4 Report from the Chief Executive Officer 6 The Board of Directors 8 Our donors 12 Volunteers 14 The year in review: 1 July 08—30 June 09 16 The Board and Advisors 18 Concise financial report 20 Contact Us 36 Cover photo: staff, family and friends of AlzNSW pose with Tim Bailey from Network Ten for a live cross for the nightly weather report to promote the 2009 Memory Walk in Parramatta. Annual Report 08-09 3 Report from the Chairman John Watkins joined us as CEO just before the last AGM and we have had a great year together. -

Annual Report 2000

Annual Report 2000 1 Annual Report 2000 Published by the Public Affairs Division The Australian National University Published by Public Affairs Division Produced by Publications Office Public Affairs Division The Australian National University Printed by University Printing and Duplicating Service Financial Services Division The Australian National University ISSN 1327-7227 April 2001 VICE-CHANCELLOR CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA PROFESSOR IAN CHUBB AO TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 2510 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6257 3292 EMAIL: [email protected] 17 April 2001 The Hon Dr David Kemp Minister for Education, Training and Youth Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister Report of the Council for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2000 We have the honour to transmit the report of the Council of The Australian National University for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2000 furnished in compliance with Section 9 of the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1977. Emeritus Professor P E Baume Professor I W Chubb Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Contents Council and University Officers Further information about ANU Overview of the University Detailed information about the achievements of ANU in 2000, especially research and teaching outcomes, is Review of 2000 contained in the annual reports of the University’s re- Council and Council Committee Meetings search schools, faculties, centres and administrative di- visions. University Statistics Cooperation with Government and For course and other academic information, other Public Institutions -

CONFERRING of AWARDS 13–16 DECEMBER 2016 MO DSA171455 Australian National Anthem

CONFERRING OF AWARDS 13–16 DECEMBER 2016 DSA171455 MO_ Australian National Anthem Advance Australia Fair Australians all let us rejoice, For we are young and free; We’ve golden soil and wealth for toil; Our home is girt by sea; Our land abounds in nature’s gifts Of beauty rich and rare; In history’s page let every stage Advance Australia Fair. In joyful strains then let us sing, Advance Australia Fair. CONFERRING OF AWARDS Summer 2016 Llewellyn Hall The Australian National University Tuesday 13 December Wednesday 14 December Thursday 15 December Friday 16 December Chancellor: Professor the Honourable Gareth Evans AC QC BA LLB (Hons) Melb, MA Oxon, HonLLD Melb, Carleton, Syd FASSA Pro-Chancellor: Ms Robin Hughes AO BA, MA Syd Vice-Chancellor: Professor Brian P. Schmidt AC FAA FRS 2011 Nobel Laureate Physics BSc (Physics) Arizona, BSc (Astronomy) Arizona, MA (Astronomy) Harvard, PhD Harvard University Marshal: Associate Professor Selwyn Cornish AM BEc(Hons) UWA University Marshal (Alternate): Ms Lorena Kanellopoulos DipHRM, GradCertMgt, MMgt ANU Esquire Bedel: Dr Ian Walker BA DipEd Syd, MA Macq, PhD UNSW Esquire Bedel (Alternate): Ms Lorena Kanellopoulos DipHRM, GradCertMgt, MMgt ANU Published by The Australian National University Conferring of Awards December 2016 1 CHANCELLOR’S MESSAGE TO GRADUANDS Today’s ceremony marks the culmination of years of research and study. ANU owes much to the intellectual and cultural contribution of our student body. In return, we work to build on our high standards in research and education. The ANU was created as part of a great nation building exercise in its day.