The Death Christ Died -A Case for Unlimited Atonement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvinism Vs Wesleyan Arminianism

The Comparison of Calvinism and Wesleyan Arminianism by Carl L. Possehl Membership Class Resource B.S., Upper Iowa University, 1968 M.C.M., Olivet Nazarene University, 1991 Pastor, Plantation Wesleyan Church 10/95 Edition When we start to investigate the difference between Calvinism and Wesleyan Arminianism, the question must be asked: "For Whom Did Christ Die?" Many Christians answer the question with these Scriptures: (Failing, 1978, pp.1-3) JOH 3:16 For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. (NIV) We believe that "whoever" means "any person, and ...that any person can believe, by the assisting Spirit of God." (Failing, 1978, pp.1-3) 1Timothy 2:3-4 This is good, and pleases God our Savior, (4) who wants all men to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth. (NIV) 2PE 3:9 The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. He is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance. (NIV) REV 22:17 The Spirit and the bride say, "Come!" And let him who hears say, "Come!" Whoever is thirsty, let him come; and whoever wishes, let him take the free gift of the water of life. (NIV) (Matthew 28:19-20 NIV) Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, (20) and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. -

Two Aspects in the Design of Christ's Atonement

Journal for Baptist Theology and Ministry Vol. 2 No. 2 (Fall 2004): 85-98 Two Aspects in the Design of Christ’s Atonement Wayne S. Hansen Associate Professor of Theology Bethel Seminary of the East 1601 N. Limekiln Pike Dresher, Pennsylvania 19025 For well over three and a half centuries Christians have been divided over one aspect of Christ’s atonement. This topic has served to separate believer from believer, often with great animosity. The cleavage is so great that it has divided schools, denominational institutions, mission agencies, and local churches. Ironically, it has been labeled as a “non-essential” by at least one side in the debate. Yet the implications for this topic are significant for one’s approach to the church, evangelism, confidence in the sovereignty of God, and especially, Christology. The topic I am alluding to is limited atonement, to use its more recognized label. Some have preferred the term “definite atonement” or “particular redemption” to emphasize the positive focus of the doctrine and eliminate any suspicion of the value of Christ’s work. But whichever term is used the basic question remains. “Did God intend to save only the elect in the death of Christ or provide salvation for all?” Passionate defenses on each side of the issue have been offered. Frequently, tensions are so strong on this issue that one side does not hear what the other is saying. Each feels justified in her/his view and often refuses to look at the other’s argument. Not a few have stated that both are true and then dismissed the subject without seeing the inconsistency of their logic. -

Calvinism and Arminianism Are Tw

K-Group week 3 Question: "Calvinism vs. Arminianism - which view is correct?" Answer: Calvinism and Arminianism are two systems of theology that attempt to explain the relationship between God's sovereignty and man's responsibility in the matter of salvation. Calvinism is named for John Calvin, a French theologian who lived from 1509-1564. Arminianism is named for Jacobus Arminius, a Dutch theologian who lived from 1560-1609. Both systems can be summarized with five points. Calvinism holds to the total depravity of man while Arminianism holds to partial depravity. Calvinism’s doctrine of total depravity states that every aspect of humanity is corrupted by sin; therefore, human beings are unable to come to God on their own accord. Partial depravity states that every aspect of humanity is tainted by sin, but not to the extent that human beings are unable to place faith in God of their own accord. Note: classical Arminianism rejects “partial depravity” and holds a view very close to Calvinistic “total depravity” (although the extent and meaning of that depravity are debated in Arminian circles). In general, Arminians believe there is an “intermediate” state between total depravity and salvation. In this state, made possible by prevenient grace, the sinner is being drawn to Christ and has the God-given ability to choose salvation. Calvinism includes the belief that election is unconditional, while Arminianism believes in conditional election. Unconditional election is the view that God elects individuals to salvation based entirely on His will, not on anything inherently worthy in the individual. Conditional election states that God elects individuals to salvation based on His foreknowledge of who will believe in Christ unto salvation, thereby on the condition that the individual chooses God. -

Calvinism Vs Arminianism Vs Evangelicalism

Calvinism vs. Arminianism vs. Evangelicalism Don’t follow any doctrine that’s named after a man (no matter how much you admire him). This chart compares the 5 points of Calvinism with the 5 points of Arminianism. Many Evangelical Christians don’t totally agree with either side but believe in a mixture of the two— agreeing with some points of Calvinism and some of Arminianism. (See the “Evangelical” chart beneath the Calvinism vs. Arminianism chart) The 5 Points of Calvinism The 5 Points of Arminianism Total Depravity Free Will Man is totally depraved, spiritually dead and Man is a sinner who has the free will to either blind, and unable to repent. God must initiate cooperate with God’s Spirit and be the work of repentance. regenerated, or resist God’s grace and perish. Unconditional Election Conditional Election God’s election is based upon His sovereignty. God’s election is based upon His His election is His own decision, and is not foreknowledge. He chooses everyone whom based on the foreseen response of anyone’s He knew would, of their own free will, respond faith and repentance. to the gospel and choose Christ. Limited Atonement Unlimited Atonement When Christ died on the cross, He shed His When Christ died on the cross, He shed His blood only for those who have been elected blood for everyone. He paid a provisional price and no one else. for all but guaranteed it for none. Irresistible Grace Resistible Grace Grace is extended only to the elect. The Saving grace can be resisted because God internal call by God’s grace cannot be resisted won’t overrule man’s free will. -

Theology 1.11

Calvinism and Arminianism Calvinism and Arminianism are two systems of theology that attempt to explain the relationship between God’s sovereignty and man’s responsibility in the matter of salvation. Calvinism is named for John Calvin, a French theologian who lived from 1509-1564. Arminianism is named for Jacobus Arminius, a Dutch theologian who lived from 1560-1609. Both systems can be summarized with five points. The Calvinists didn’t come up with five points to start with. The Calvinists wrote their vision of what salvation looks like and how it happens under God’s sovereignty. When the Arminians read it, they said, “These are five places we don’t agree.” That is where we got these five points. 1. Depravity • Calvinism’s doctrine of total depravity states that every aspect of humanity is corrupted by sin; therefore, human beings are so depraved and rebellious that they are unable to trust God and come to Him on their own accord without God’s special work of grace to change their hearts. • Arminians say, with regard to depravity, that people are depraved and corrupt, but they are able to provide the decisive impulse to trust God with the general divine assistance that God gives to everybody. Although some refer to this as “partial depravity”, classical Arminianism rejects “partial depravity” and holds a view very close to Calvinistic “total depravity” (although the extent and meaning of that depravity are debated in Arminian circles). 2. Election • Calvinism includes the belief that election is unconditional. It says that we are chosen. God chooses unconditionally whom he will mercifully bring to faith and whom he will justly leave in their rebellion. -

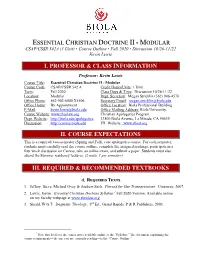

Course Outline • Fall 2020 • Discussion 10/26-11/22 Kevin Lewis

ESSENTIAL CHRISTIAN DOCTRINE II - MODULAR CSAP/CSSR 542A (1 Unit) • Course Outline • Fall 2020 • Discussion 10/26-11/22 Kevin Lewis I. PROFESSOR & CLASS INFORMATION Professor: Kevin Lewis Course Title: Essential Christian Doctrine II - Modular Course Code: CSAP/CSSR 542 A Credit Hours/Units: 1 Unit Term: Fall 2020 Class Days & Time: Discussion 10/26-11/22 Location: Modular Dept. Secretary: Megan Stricklin (562) 906-4570 Office Phone: 562-903-6000 X5506 Secretary Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Office Location: Biola Professional Building E-Mail: [email protected] Office Mailing Address: Biola University, Course Website: www.theolaw.org Christian Apologetics Program, Dept. Website: http://biola.edu/apologetics 13800 Biola Avenue, La Mirada, CA 90639 Discussion: http://canvas.biola.edu ITL Website: www.itlnet.org II. COURSE EXPECTATIONS This is a required, two-semester (Spring and Fall), core apologetics course. For each semester, students must carefully read the course outline, complete the assigned readings, participate in a four week discussion on Canvas, take an online exam, and submit a paper. Students must also attend the Summer residency lectures. (2 units, 1 per semester) III. REQUIRED & RECOMMENDED TEXTBOOKS A. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Jeffery, Steve, Michael Ovey & Andrew Sach. Pierced for Our Transgressions. Crossway, 2007. 2. Lewis, Kevin. Essential Christian Doctrine Syllabus.1 Fall 2020 Version. Available online on my faculty webpage at www.theolaw.org. 3. Shedd, W.G.T. Dogmatic Theology. 3rd Ed., Grand Rapids: P & R Publishers, 2003. 1 Note that I refer to the course notes available online as the “Syllabus.” The document explaining the course requirements—the one you are currently reading—is the “Course Outline.” ECD II-Modular-Fall Semester Course Outline Page 2 B. -

THE ERRORS of CALVINISM VS. the BIBLICAL VIEW of GOD and MAN by Roger L

THE ERRORS OF CALVINISM VS. THE BIBLICAL VIEW OF GOD AND MAN by Roger L. Berry STUDY GUIDE LESSON 1: What Is Calvinism and Arminianism? ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2 LESSON 2: Principles of Biblical Interpretation ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 LESSON 3: The Christian View of Man ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 LESSON 4: The Christian View of God ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 11 LESSON 5: The Christian View of Christ . 14 LESSON 6: The Grace of God ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 LESSON 7: The Security of the Believer ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 LESSON 8: The Security of the Believer (continued) ��������������������������������������������������������������������������� 23 LESSON 9: Influences of Calvinism ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 27 LESSON 10: The Dangers of Calvinism ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 31 Copyrighted material. May not be reproduced without permission from the publisher. Copyrighted material. May not be reproduced without permission from the publisher. NOTE: Questionable Teaching in Life In the Son And Elect in the -

Limited Atonement

The Doctrine of Limited Atonement 2009 Bible Conference Jalan Imbi Chapel Kaula Lampur Aurelius Augustine —Born in Thagaste, Africa, AD 354 —Professor of Rhetoric & Speech at Univeristy of Milan —Debated Pelagius AD 410-12 —His writings inspired the thinking of John Calvin. Church History Athanasius (AD 293-373) “Thus, taking a body like our own, because all our bodies were liable to the corruption of death, He surrendered His body to death instead of all...” “...Death there had to be, and death for all so that the due of all might be paid.” Limited Atonement Heidelberg Catechism 1563 “...What do you understand by the ‘suffered’ —That all the time Christ lived on the earth, but especially at the end of His life, He bore, in body and soul, the wrath of God, against the sin of the whole human race...” —37th Question - Doctrinal Standard of the German Reformed Church Limited Atonement “ The Thirty Nine Articles” (1553) “The offering of Christ once made is that perfect redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction, for all the sins of the whole world, both original and actual, and there is none other satisfaction for sin, but that sin alone” —The official statement of faith for the Church of England Limited Atonement Dr. Walter Elwell, Presbyterian scholar “Those who defend unlimited atonement point out that it is the historic view of the church...it was held by Luther, Melanchthon, Bullinger, Coverdale,and even Calvin, in some of his commentaries.” Martin Luther (1483-1546), Richard Hooker (1553-1600), John Bunyan (1628-1688), J. B. Lightfoot (1828-1889), Augustus Strong (1836-1921), A. -

Names of Jesus

NOW I KNOW MY ABC`S JESUS IS IN EVERY LETTER OF OUR ALPHABET A = Alpha, Ancient of days, Amen and our Anchor. B = Bread of life, Beginning and end, Bright and morning star, Bishop and Bridge-groom. C = Captain and the Cornerstone. D = Day-star from on high, Gods front Door and our Deliverer. E = Everlasting love, Everlasting Father, Eternal Life and our El Shaddai F = Fountain of life, First and last, Foundation of our faith and Fairest among ten thousand. G = Glory of his people Israel, the Good Shepard and the Gate. H = Head of the all things, Healing balm of Gilead and our High Priest. I = Intercessor and Immanuel God with us. J = Judge of all the earth, Jesus our Savior and Jehovah – God. K = King of kings and our Kinsman Redeemer. L = Loin of the tribe of Judah, Lilly of the valley, Light of the world and Lord of lords. M = Mediator, Manna, Might God, Melchizedek of the New Testament and Messiah. N = Nazarene and Name above all names. O = Omega, O spring of David and Over-comer. P = Prophet, Promise of God, Prince of Peace and our Passover Lamb. Q = Quail from heaven R = Redeemer, Rock, Root of Jesse, Rose of Sharon and the Resurrection. S= Son of God, Scape Goat, Sword, Shield and Sacrifice for sin. T = Tree of life, Teacher, Tabernacle and the Truth. U = Undefiled and the Unlimited Atonement. V = Veil rent from top to bottom and the Vine. W = Water of life, the Way, Word make flesh and Wonderful counsellor mighty God. -

DES Ignite2017 Daily

IGNITE 2 0 1 7 WORKBOOK Calvinism (Day One) DAY ONE Calvinism vs. Arminianism (Day Two) (Adapted from Dr. Tim Beougher, Ph.D.) 1. WHY STUDY ARMINIANISM AND CALVINISM? a. Significant regarding church history b. Your interpretive lens needs to be accurate c. The issues raised by Arminianism and Calvinism relate to eternal salvation (key questions!) 2. HOW SHOULD ONE APPROACH THIS ISSUE? a. Focus: “What does the Bible teach?” b. Attitude: humility and charity (unfortunately a lot of mean-spirited attacks on both sides of the issue) 3. BACKGROUND: a. Arminians submitted 5 points to the Church of Holland in 1610. b. Synod of Dort in 1619 responded with the 5 points of Calvinism (TULIP) TOTAL DEPRAVITY [Radical Corruption] 1. Key Question: How great is the effect of the Fall? Do we have “free will” to accept or reject Christ? 2. Scriptural References (Calvinism) a. Eph. 2:1-3; Rom. 3:1-23 (esp. 9-11); John 6:44; Jer. 17:9 b. Ephesians 2: 1 -- “And you were dead in your trespasses and sins . .” c. Total (not ABSOLUTE) depravity [radical corruption] -- we are not as bad as we can be Total inability -- the sinner cannot convert himself d. The emphasis is not on Physical inability but Moral inability; Mankind “can” believe but he “won’t” believe. LIMITED/Unlimited ATONEMENT [Definite Atonement] (For whom did Christ die?) 1. Some argue that Christ died only for the elect, while others emphasize that the death of Christ was universal -- He died for everyone even though not everyone will be saved. AREAS OF AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE TWO POSITIONS: a. -

Foundations of Systematic Theology Systematic Foundations Of

ST408 Foundations of Systematic Theology LESSON 11 of 24 Christology: The Work of Christ John M. Frame, D.D. Experience: Professor of systematic theology at Reformed Theological Seminary In lesson 10, we asked about the person of Christ. What kind of person Jesus is? We saw that He is both true God and true man— two distinct natures in one person. In this lesson, we will ask about the work of Christ. What does Jesus do for us? I’ll be talking about His work in terms of His offices. Just as some people are presidents or mayors or sergeants or CEOs or certified public accountants, so Jesus holds certain offices. And what He does, His actions, carry out the duties of those offices. What are those offices? Well as we’ve seen, Jesus is the Messiah, the Anointed One. That idea sends us back to the Old Testament where three offices of people were anointed with oil: prophets, priests, and kings. When the Messiah comes—the Anointed One, par excellence—He holds all three of these offices and indeed fulfills them. He is the ultimate prophet, the ultimate priest, and the ultimate king. You may recall the threefold concept of lordship that I shared with you in lesson one. These three offices fit right in with that. As prophet, Jesus displays the lordship attribute of authority. As priest, the lordship attribute of presence, and as king, the lordship attribute of control. Or in terms of our distinctions in lesson six, the prophet represents the normative perspective; the priest, the existential; and the king, the situational. -

Protestant Reformed Theological Journal

PROTESTANT REFORMED THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL -- I NOVEMBER, 1989 VOLUME XXIII, No. '~ r THEOLOGICAL SCHOOL OF THE PROTESTANT REFORMED CHURCHES GRANDVILLE, MICHIGAN NOVEMBERt 1989 Volume XXIII, No.1 PROTESTANT REFORMED THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL Edited for the faculty of The Theological School of the Protestant Reformed Churches Robert D. Decker David J. Engelsma Herman C. Hanko by Prof. Hennan Hanko (editor-in-chief) Prof. Robert Decker (editor. book reviews) The Protestant Reformed Theological Journal is published semiannually, in April and November, and distributed in limited quantities, at no charge. by the Theological School of the Protestant Reformed Churches. Interested persons desiring to have their names on the mailing list should write -the Editor, at the address below. Books for review should be sent to the book review editor, also at the address of the school. Protestant Reformed Seminary 49491vanrest Avenue Grandville, MI 49418 NOVEMBER, 1989 Volume XXIII, No.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Edit~rial Notes 2 The Doctrine of I)redcstination in Calvin and Beza Prof. Herman C. Hanko 3 Calvin's Doctrine of the Trinity Prof. David]. Engclsma 19 Book Reviews 37 Book Notices 60 EDITORIAL NOTES Our readers will note that this issue of The Journal includes no article by Prof. H.C. Hoeksema. We will not receive articles from him again. for on July 17 the Lord took him to glory after a shon illness from cancer. Our readers will recall that Prof. Hoeksema had spent the past year, be ginning in August of 1988, laboring in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Burnie, Australia. It was, in many respects, a happy v,lay for Prof.