The Escape of the Goeben and Breslau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telling the Story of the Royal Navy and Its People in the 20Th & 21St

NATIONAL Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people MUSEUM in the 20th & 21st Centuries OF THE ROYAL NAVY Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report JULY 2011 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE ROYAL NAVY Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people in the 20th & 21st Centuries Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report 2 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT Contents Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 2.0 Introduction 2.1 Vision, Goal and Mission 2.2 Strategic Context 2.3 Exhibition Objectives 3.0 Design Brief 3.1 Interpretation Strategy 3.2 Target Audiences 3.3 Learning & Participation 3.4 Exhibition Themes 3.5 Special Exhibition Gallery 3.6 Content Detail 4.0 Design Proposals 4.1 Gallery Plan 4.2 Gallery Plan: Visitor Circulation 4.3 Gallery Plan: Media Distribution 4.4 Isometric View 4.5 Finishes 5.0 The Visitor Experience 5.1 Visuals of the Gallery 5.2 Accessibility 6.0 Consultation & Participation EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 3 Ratings from HMS Sphinx. In the back row, second left, is Able Seaman Joseph Chidwick who first spotted 6 Africans floating on an upturned tree, after they had escaped from a slave trader on the coast. The Navy’s impact has been felt around the world, in peace as well as war. Here, the ship’s Carpenter on HMS Sphinx sets an enslaved African free following his escape from a slave trader in The slave trader following his capture by a party of Royal Marines and seamen. the Persian Gulf, 1907. 4 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 1.0 Executive Summary 1.0 Executive Summary Enabling people to learn, enjoy and engage with the story of the Royal Navy and understand its impact in making the modern world. -

Royal United Service Institution

Royal United Services Institution. Journal ISSN: 0035-9289 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rusi19 Royal United Service Institution To cite this article: (1911) Royal United Service Institution, Royal United Services Institution. Journal, 55:400, iii-xxi, DOI: 10.1080/03071841109434568 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03071841109434568 Published online: 11 Sep 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 4 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rusi20 Download by: [University of California, San Diego] Date: 26 June 2016, At: 13:09 Royal United Service Institution: rHE EIGHTIETHANNIVERSARY MEETING WAS HELD AT. THE ROYALUNITED SERVICE INSTITUTION, WHITEHALL; S.W., ON TUESDAY,MARCH 7TH, 191 1, AT 4 P.M. ADMIRALOF THE FLEET,Sir C. H. U. NOEL,K.C.B., K.C.M.C.,(Chairman of the Council) tn the CHAIR. THECHAIRMAN : Gentlemen, the Secretary will' read the notice -cynvcning the meeting. .. THESECRETARY (Lieutcnant.Colone1 A.. Leetham) read the notice. 1 ANNUAL REPORT. ThecCcuncil has the hcncur to sutmit itr rcpcrt for the year 1910. .. I " PATRON;'. , , , . His Majesty King George V,'has graciously intimated that he is picad '1 to become Patron of the Institution. .I . t ROYALVISITS. During the year the Institution was visited by His Late Ma$y King Edward VII., Hir' vajesty King'iCcorge V., Her Majeaty The Queen, Hkr Majesty QuLn Alexandra, 'His Roxal' Highniss' Prince Hcnr). of Pruuia. Their RoyJl'Highnesses the Crown Pricce and Princess of Si-eded, His Royal Hiihrmi Prince' H:n&, Field hlarihal IHh.Roybl Hi8hr.e~ 'The Duke' of Connaught, K,C.'(Prcsidcnt of' the 'Inrtitutwn) -. -

My War at Sea 1914–1916

http://www.warletters.net My War at Sea: 1914–1916 Heathcoat S. Grant Edited by Mark Tanner Published by warletters.net http://www.warletters.net Copyright First published by WarLetters.net in 2014 17 Regent Street Lancaster LA1 1SG Heathcoat S. Grant © 1924 Published courtesy of the Naval Review. Philip J. Stopford © 1918 Published courtesy of the Naval Review. Philip Malet de Carteret letters copyright © Charles Malet de Carteret 2014. Philip Malet de Carteret introduction and notes copyright © Mark Tanner 2014. ISBN: 978-0-9566902-6-5 (Kindle) ISBN: 978-0-9566902-7-2 (Epub) The right of Heathcoat S. Grant, Philip J. Stopford, Philip Malet de Carteret and Mark Tanner to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. This publication may be shared and distributed on a non-commercial basis provided that the work remains in its entirety and no changes are made. Any other use requires the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Naval Review c/o http://www.naval-review.com Charles Malet de Carteret c/o St Quen’s Manor, Jersey Mark Tanner c/o http://warletters.net http://www.warletters.net Contents Contents 4 Preface 5 1: From England to South America 7 2: German Ships Approaching 12 3: The Coronel Action 17 4: The Defence of the Falklands 19 5: The Battle of the Falklands 25 6: On Patrol 29 7: To the Dardanelles 33 8: Invasion Preparations 41 9: Gallipoli Landings 45 10: At Cape Helles 49 11: Back to Anzac 51 12: The Smyrna Patrol 56 13: The Suvla Landings 61 14: The Smyrna Patrol (Continued) 63 15: Sick Leave in Malta 67 16: Evacuation 69 17: Operations Against Smyrna 75 18: Report on Operations 82 19: Leaving for Home 85 APPENDICES 87 1: Canopus Officers 87 2: Heathcoat S. -

Philip Wilcocks CB DSC DL ‒ Onboarding Officers Super

Philip Wilcocks CB DSC DL – OnBoarding Officers Super NED Joining the Royal Navy in 1971, Philip Wilcocks graduated from the University of Wales in 1976 and assumed his first command of the minesweeper HMS STUBBINGTON in 1978. Qualifying as a Principal Warfare Officer in 1981, he served in the frigate HMS AMBUSCADE as Operations Officer, which included the Falklands conflict in 1982. Following his promotion to Commander, he assumed command of the destroyer HMS GLOUCESTER in 1990. The ‘Fighting G’ fought in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm when his ship destroyed 7 enemy warships and a Silkworm missile targeted against the battleship USS MISSOURI. He was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry and sustained leadership under fire. In 1998, he assumed command of HMS LIVERPOOL as Captain 3rd Destroyer Squadron. While Director of Naval Operations, in 2000 he was the Crisis Director for UK Operations in support of the UN in Sierra Leone. In 2001, he formed and then commanded the Royal Navy’s largest training organisation the Maritime Warfare School responsible for a budget of £120M and a capital build programme of £30M. On promotion to Rear Admiral in 2004, he became Deputy Commander of Joint Operations at the UK’s Permanent Joint HQ; as well as operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, he was the Crisis Director for the UK response to the 2005 Tsunami disaster. In this appointment he had oversight of an annual budget of £540M and a £1.5Bn PFI contract. Following a short tour as Flag Officer Scotland, Northern England and Northern Ireland and Flag Officer Reserves, he became Chief of Staff to Commander-in-Chief, Fleet assuming responsibility for generating current and future UK maritime capabilities. -

The Royal Naval Surgeons in the Battle of Coronel

J Royal Naval Medical Service 2015, Vol 101.1 28 The Royal Naval surgeons in the battle of Coronel Dr D Mahan In Memoriam: the Royal Naval surgeons of HMS GOOD These men performed their duties right to the end and HOPE and HMS MONMOUTH. were fi nally laid to rest in the deep water that covers all and gradually erodes the glorious remains of sunken ships, Introduction until time fi nally dissolves them completely. Among these The battle of Coronel was the fi rst British defeat in the sailors we should, as fellow doctors, commemorate the First World War and is not often remembered. It played surgeons who, out of pure vocation or given the imperative out in the southern Pacifi c Ocean, off the coast of Chile. of serving their country, enlisted as offi cers in warships On 1 November 1914, the Royal Navy (RN) confronted to take care of the welfare of their crews and attend the a German squadron outside the port of Coronel (36º 59’ wounds of those fallen in combat. However, from the mid- 26.24’’ S, 73º 37’ 53.39’’ W), close to Chile’s second city 19th century, naval artillery acquired such an enormous of Concepción. The Germans won a resounding victory, destructive capacity, capable of penetrating even the most sinking two of the four British ships (HMS GOOD HOPE powerful armour plates, that during the short moments of and HMS MONMOUTH) with the loss of over 1600 naval engagement, shellfi re created such a terrible level of lives. The British responded quickly and forcefully. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Diary of Leading Stoker Victor Bethell HMS Gloucester 1916

Diary of Leading Stoker Victor Bethell, HMS Gloucester, 26th April – 5th June 1916 HMS Gloucester was a Town-class light cruiser that took part in the first naval encounter of the war, the chase of the German battlecruiser SMS Goeben and the light cruiser SMS Breslau in the Mediterranean, during which she engaged and hit Breslau. In May 1916, she was back in home waters with the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron, part of the Grand Fleet’s Battlecruiser fleet. The extract below covers the Irish Easter Rising and the Battle of Jutland. A Leading Stoker was in charge of a group of stokers, whose job was to shovel coal into the furnaces of a ship’s boilers. Known as the ‘Black Gang’, they did hot, hard work in the bowels of the ship. Wednesday 26th April: At Queenstown. We take onboard 100 Royal Marines and proceed to Galway Bay, on the west coast of Ireland. Thursday 27th April: We arrive at Galway and land the soldiers to stop the Sinn Féin rising. The Irish Police bring aboard five leaders and we held them prisoners. Friday 28th April: Troopship arrives and they land more soldiers. Wednesday 10th May: Still at Galway. HMS Adventure relieves us and we proceed to Queensferry in the Firth of Forth. Friday 12th May: Arrived at Queensferry. Tuesday 30th May: Left Queensferry with the fleet and go full speed for Germany. Wednesday 31st May: At four pm, enemy sighted and our battlecruisers open fire. We were alongside the battlecruisers (HMS Lion flagship) about the moment that HMS Invincible was blown up and sank in a few minutes (she was off the port side of us). -

75Th Anniversary of the Sinking of HMS Gloucester 1941 Canon Chancellor Celia Thomson

Sermon: Trinity Sunday 22 May - 75th anniversary of the sinking of HMS Gloucester 1941 Canon Chancellor Celia Thomson 75 years ago today, HMS Gloucester was sunk off the north coast of Crete with the loss of 723 lives out of the total crew of 809. It was one of the worst naval disasters of the second World War and there are very few left now of those who survived to tell the tale. We have a window in the Memorial Chapel dedicated to the memory of those who died, and each year there is a gathering there to remember them. We also have the shield of the last of the ships named HMS Gloucester in the north transept. It is only right that today we honour those who gave their lives in the service of their country. When the German forces overran the Greek mainland in April 1941, almost all the Allied troops, about 50,000, were evacuated to Crete. But they had had to leave behind most of their heavy armoured vehicles, tools and ammunition, and were therefore ill-equipped to defend the island. The Battle for Crete was one of the most dramatic battles of the Second World War. Over 12 days in May 1941 a mixed force of British, Australian, New Zealand and Greek troops desperately tried to fight off a huge German airborne assault. Despite the appalling casualties amongst the Germans themselves, those who led the invasion by parachute and the glider-borne troops managed to secure a foothold on the island and eventually take it over. -

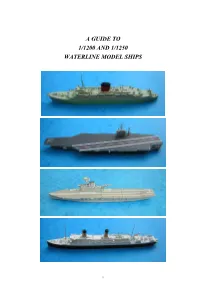

Model Ship Book 4Th Issue

A GUIDE TO 1/1200 AND 1/1250 WATERLINE MODEL SHIPS i CONTENTS FOREWARD TO THE 5TH ISSUE 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Aim and Acknowledgements 2 The UK Scene 2 Overseas 3 Collecting 3 Sources of Information 4 Camouflage 4 List of Manufacturers 5 CHAPTER 2 UNITED KINGDOM MANUFACTURERS 7 BASSETT-LOWKE 7 BROADWATER 7 CAP AERO 7 CLEARWATER 7 CLYDESIDE 7 COASTLINES 8 CONNOLLY 8 CRUISE LINE MODELS 9 DEEP “C”/ATHELSTAN 9 ENSIGN 9 FIGUREHEAD 9 FLEETLINE 9 GORKY 10 GWYLAN 10 HORNBY MINIC (ROVEX) 11 LEICESTER MICROMODELS 11 LEN JORDAN MODELS 11 MB MODELS 12 MARINE ARTISTS MODELS 12 MOUNTFORD METAL MINIATURES 12 NAVWAR 13 NELSON 13 NEMINE/LLYN 13 OCEANIC 13 PEDESTAL 14 SANTA ROSA SHIPS 14 SEA-VEE 16 SANVAN 17 SKYTREX/MERCATOR 17 Mercator (and Atlantic) 19 SOLENT 21 TRIANG 21 TRIANG MINIC SHIPS LIMITED 22 ii WASS-LINE 24 WMS (Wirral Miniature Ships) 24 CHAPTER 3 CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURERS 26 Major Manufacturers 26 ALBATROS 26 ARGONAUT 27 RN Models in the Original Series 27 RN Models in the Current Series 27 USN Models in the Current Series 27 ARGOS 28 CM 28 DELPHIN 30 “G” (the models of Georg Grzybowski) 31 HAI 32 HANSA 33 NAVIS/NEPTUN (and Copy) 34 NAVIS WARSHIPS 34 Austro-Hungarian Navy 34 Brazilian Navy 34 Royal Navy 34 French Navy 35 Italian Navy 35 Imperial Japanese Navy 35 Imperial German Navy (& Reichmarine) 35 Russian Navy 36 Swedish Navy 36 United States Navy 36 NEPTUN 37 German Navy (Kriegsmarine) 37 British Royal Navy 37 Imperial Japanese Navy 38 United States Navy 38 French, Italian and Soviet Navies 38 Aircraft Models 38 Checklist – RN & -

The London of TUESDAY, the Zgth of JULY, 1947 by Finfyotity Registered As a Newspaper THURSDAY, 31 JULY, 1947 BATTLE of MATAPAN

(ftumb. 38031 3591 THIRD SUPPLEMENT TO The London Of TUESDAY, the zgth of JULY, 1947 by finfyotity Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, 31 JULY, 1947 BATTLE OF MATAPAN. 4. The disposition originally ordered left the The following Despatch was submitted to the cruisers without support. The battlefleet could Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on the if necessary have put to sea, but very nth November, 1941, by Admiral Sir inadequately screened. Further consideration Andrew B. Cunningham, G.C.B., D.S.O., led to the retention of sufficient destroyers to Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Station. screen the battlefieet. The moment was a lucky one when more destroyers than usual Mediterranean, were at Alexandria having just returned from ntffe November,. 1941. or just awaiting escort duty. Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships the 5. It had already been decided to take the attached reports of the Battle of Matapan, 27th- battlefleet to sea under cover of night on the 30th March, 1941. Five ships of the enemy evening of the 27th, when air reconnaissance fleet were sunk, burned or destroyed as per from Malta reported enemy cruisers steaming margin.* Except for the loss of one aircraft eastward p.m./27th. The battlefleet accordingly in action, our fleet suffered no damage or proceeded with all possible secrecy. It was casualties. well that it did so, for the forenoon of the 28th 2. The events and information prior to the found the enemy south of Gavdo and the Vice- action, on which my appreciation was based, Admiral, Light Forces (Vice-Admiral H. -

York Minster Conservation Management Plan 2021

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOL. 2 GAZETTEERS DRAFT APRIL 2021 Alan Baxter YORK MINSTER CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOL. 2 GAZETTEERS PREPARED FOR THE CHAPTER OF YORK DRAFT APRIL 2021 HOW TO USE THIS DOCUMENT This document is designed to be viewed digitally using a number of interactive features to aid navigation. These features include bookmarks (in the left-hand panel), hyperlinks (identified by blue text) to cross reference between sections, and interactive plans at the beginning of Vol III, the Gazetteers, which areAPRIL used to locate individual 2021 gazetteer entries. DRAFT It can be useful to load a ‘previous view’ button in the pdf reader software in order to retrace steps having followed a hyperlink. To load the previous view button in Adobe Acrobat X go to View/Show/ Hide/Toolbar Items/Page Navigation/Show All Page Navigation Tools. The ‘previous view’ button is a blue circle with a white arrow pointing left. York Minster CMP / April 2021 DRAFT Alan Baxter CONTENTS CONTENTS Introduction to the Gazetteers ................................................................................................ i Exterior .................................................................................................................................... 1 01: West Towers and West Front ................................................................................. 1 02: Nave north elevation ............................................................................................... 7 03: North Transept elevations....................................................................................