China's Banking System and How Citibank Can Capitalize on Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. V. Connie Moorman Willis

Case 5:17-mj-01008-PRL Document 1 Filed 02/07/17 Page 1 of 14 PageID 1 AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the Middle District of Florida United States of America ) v. ) ) CONNIE MOORMAN WILLIS Case No. ) 5: 17-mj-1008-PRL ) ) ) Defendant(s) I CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I i I, 1~he complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. On or about the date(s) of Feb. 4, 2011 through Jan. 25, 2016 in the county of Marion in the I Middle District of Florida , the defendant(s) violated: ! j Code Section Offense Description 18 u.s.c. 1 sec. 656 Theft by a Bank Employee 18 U.S.C. Sec. 1341 Mail Fraud Tnis criminal complaint is based on these facts: I I See attached affidavit. I lifl Continued on the attached sheet. Charles Johnsten, U.S. Postal Inspector Printed name and title Sworn to before me and signed in my presence. Date: ~-1 - :lo Ir City and siate: Ocala, Florida Philip R. Lammens, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title I ! Case 5:17-mj-01008-PRL Document 1 Filed 02/07/17 Page 2 of 14 PageID 2 S'FATE OF FLORIDA CASE NO. 5:17-mj-1008-PRL I IOUNTY OF MARION AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT OF A CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, Charles Johnsten, being duly sworn, state as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. I am a United States Postal Inspector and have been so employed since I obcember 2016. -

NETSUITE ELECTRONIC BANK PAYMENTS Securely Automate EFT Payments and Collections with a Single Global Solution

NETSUITE ELECTRONIC BANK PAYMENTS Securely Automate EFT Payments and Collections with a Single Global Solution Electronic Bank Payments brings to NetSuite complementary electronic banking functionality Key Features that includes Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) • Automated payment batch allows multiple payments, customer refunds and customer payment batch creation stemmed from payments (direct debits), as well as check fraud different batch criteria, controls and payment deadlines. prevention through the Positive Pay service offered by leading banks. It helps ensure that • Approval routing and email alert notification enables additional payment employees and vendors are paid on time authorization prior to payment processing. and customer bills are settled automatically. With support for a wide range of global and • Enhanced EFT capabilities with filtering options support bill display, partial payments, local bank formats, Electronic Bank Payments bill management and other controls. provides a single payment management • Automated direct debit customer solution worldwide. collections to settle outstanding invoices. Electronic Bank Payments creates files of • Payment management options include payments or direct debit information in bank’s payment batch queuing, rollbacks, reversals predefined file format ready for import into with notations and automated notifications. banking software or submission to the bank • Positive Pay anti-fraud capabilities with online, thus lowering payment processing proactive notification to banks processing expenses by eliminating checks, postage and the checks. envelopes, and saving time as well. In addition, • Support for more than 50 international it supports management of large payment bank formats with Advanced Electronic runs (typically up to 5,000 payments per file) Bank Payment License customers having with the ability to process reversals and partial the flexibility to add more. -

Update on the Proposed Changes to Our Business As the UK Leaves the European Union

Citibank Europe plc, UK Branch 0808 109 8888 or Level 10, Citigroup Centre 1 +44 207 500 1445 33 Canada Square (if calling from outside the UK) London E14 5LB ipb.citi.com United Kingdom International Personal Bank November 2018 Update on the proposed changes to our business as the UK leaves the European Union As we continue to make progress with establishing our new UK Bank, I wanted to share with you an update on the changes we are proposing to our Citi International Personal Bank business further to our initial correspondence dated October 2018. I hope that after reading the more detailed information provided below, you will be assured that we remain dedicated to serving your banking and wealth needs. What is changing? In preparation for the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union (“EU”), we recently wrote to you about our intentions to establish a new UK Bank, headquartered in London, and transfer our Citi International Personal Bank business from Citibank Europe plc, UK Branch, headquartered in Ireland, to our newly-created UK Bank (known as the “Proposed Transfer”). The company that will become our new UK Bank is called “Citibank UK Limited”. What has happened so far? We have already applied to the UK Regulators for permission to set up the new UK Bank and have now asked the High Court of Justice in England and Wales (the “Court”) to approve the Proposed Transfer, which is currently progressing as planned. If the UK Regulators authorise the new UK Bank and the Court approves the Proposed Transfer, we intend to transfer the Citi International Personal Bank business to our new UK Bank in March 2019, at which point it will be fully operational. -

Brown Brothers Harriman Global Custody Network Listing

BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN GLOBAL CUSTODY NETWORK LISTING Brown Brothers Harriman (Luxembourg) S.C.A. has delegated safekeeping duties to each of the entities listed below in the specified markets by appointing them as local correspondents. The below list includes multiple subcustodians/correspondents in certain markets. Confirmation of which subcustodian/correspondent is holding assets in each of those markets with respect to a client is available upon request. The list does not include prime brokers, third party collateral agents or other third parties who may be appointed from time to time as a delegate pursuant to the request of one or more clients (subject to BBH's approval). Confirmations of such appointments are also available upon request. COUNTRY SUBCUSTODIAN ARGENTINA CITIBANK, N.A. BUENOS AIRES BRANCH AUSTRALIA CITIGROUP PTY LIMITED FOR CITIBANK, N.A AUSTRALIA HSBC BANK AUSTRALIA LIMITED FOR THE HONGKONG AND SHANGHAI BANKING CORPORATION LIMITED (HSBC) AUSTRIA DEUTSCHE BANK AG AUSTRIA UNICREDIT BANK AUSTRIA AG BAHRAIN* HSBC BANK MIDDLE EAST LIMITED, BAHRAIN BRANCH FOR THE HONGKONG AND SHANGHAI BANKING CORPORATION LIMITED (HSBC) BANGLADESH* STANDARD CHARTERED BANK, BANGLADESH BRANCH BELGIUM BNP PARIBAS SECURITIES SERVICES BELGIUM DEUTSCHE BANK AG, AMSTERDAM BRANCH BERMUDA* HSBC BANK BERMUDA LIMITED FOR THE HONGKONG AND SHANGHAI BANKING CORPORATION LIMITED (HSBC) BOSNIA* UNICREDIT BANK D.D. FOR UNICREDIT BANK AUSTRIA AG BOTSWANA* STANDARD CHARTERED BANK BOTSWANA LIMITED FOR STANDARD CHARTERED BANK BRAZIL* CITIBANK, N.A. SÃO PAULO BRAZIL* ITAÚ UNIBANCO S.A. BULGARIA* CITIBANK EUROPE PLC, BULGARIA BRANCH FOR CITIBANK N.A. CANADA CIBC MELLON TRUST COMPANY FOR CIBC MELLON TRUST COMPANY, CANADIAN IMPERIAL BANK OF COMMERCE AND BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON CANADA RBC INVESTOR SERVICES TRUST FOR ROYAL BANK OF CANADA (RBC) CHILE* BANCO DE CHILE FOR CITIBANK, N.A. -

Factsheetchina EN 01

Fact Sheet Citi China WHO WE ARE Citi Inc. (NYSE: C) Citi is a leading global bank in China. We first opened our doors here in 1902, and became one of the first international banks to establish an incorporated entity in 2007. Citi’s Global Coverage 6 continents Today, we bank close to 1,000 MNCs - including about 70% of Fortune 500 companies - More than 160 countries over 350 local corporates and over 2,300 emerging corporates and middle corporates. By and jurisdictions listed market cap, we bank 85% of the largest 20 companies in China. We also have 128 currencies dedicated China desks across the world supporting Chinese clients across our global 200 million customer accounts network. We raised over US$30 billion for Chinese clients in 2020 from global capital markets, CCCL Credit Rating: including in Hong Kong and New York. We serve our Chinese clients with around 6,000 AAA (S&P colleagues across 16 locations. China, 2020) Citi China remains resilient despite the impact of COVID-19. At the height of the outbreak in Citigroup Tower China, we supported our clients and processed 100% of our transactions on time while No.33 Hua Yuan Shi Qiao Road Lu Jia Zui Finance accelerating digitization. and Trade Zone Shanghai, 200120, QUICK FACTS P.R. China Tel: +86 21 2896 6000 • Citibank (China) Co., Ltd. (“CCCL”) (est. 2007) is 100% www.citi.com.cn owned by parent Citibank N. A. •The bank has a presence across 12 major Chinese cities, Press Contacts including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, Marine Mao and lending companies in four other locations serving +86 21 2896 6366 rural counties and towns. -

Natwest Group Plc H1 2020 Results Update for Fixed Income Investors

Page 1 NatWest Group plc H1 2020 Results Update for Fixed Income Investors Moderators: Katie Murray & Donal Quaid 31 st July 2020 This transcript includes certain statements regarding our assumptions, projections, expectations, intentions or beliefs about future events. These statements constitute “forward-looking statements” for purposes of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. We caution that these statements may and often do vary materially from actual results. Accordingly, we cannot assure you that actual results will not differ materially from those expressed or implied by the forward-looking statements. You should read the section entitled “Forward-Looking Statements” in our H1 Results announcement published on 31 st July 2020. Page 2 OPERATOR: This is conference #7584097. Operator: Welcome, everyone. We will now play a pre-recorded audio presentation of our Fixed Income Results. This will be followed by a live Q&A session with Katie Murray and Donal Quaid. Katie Murray: Good afternoon, everyone. Thank you for joining us this afternoon for our fixed income H1 results presentation. I am joined by Donal Quaid, our Treasurer, and I will take you through our headlines then move into the detail, including a breakdown of the impairment charge and the scenarios we have used to model expected credit loss under IFRS 9. Donal will then take you through the balance sheet, capital and liquidity, and give you an update on issuance plans, and we’ll open the call at the end for Q&A. So, let me start on Slide 3 with the headlines. We’ve had a strong start to the year before the impact of COVID-19, and our pre-impairment operating profit for the first half was GBP2.1 billion. -

Citigroup Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2010 Commission file number 1-9924 Citigroup Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 52-1568099 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 399 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10043 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 559-1000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: See Exhibit 99.01 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: none Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes X No Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes X No Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. X Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit and post such files). -

Natwest-Markets-Nv-Cash-Ssi.Pdf

NatWest Markets N.V., AMSTERDAM Standard Settlement Instruction (cash) for Foreign Exchange, Money Market, Currency Options, FRAs, Interest Rate & Commodity Swaps, Interest Rate & Commodity Options, Fixed Income, Collateral, Credit Derivatives and Exchange Traded Futures & Options & Equity Derivatives Transactions. All accounts are in the name of NatWest Markets N.V., Amsterdam OMGEO Alert Acronym is RBSFMFX. Model Name is NWMNV. Effective From 15/04/2019 Correspondent Swift Beneficiary ISO CCY Country Correspondent Details Account Number Address Swift Code United Arab 1012003958924016 AED NBADAEAA National Bank of Abu Dhabi RBOSNL2RTCM Emirates IBAN - AE540351012003958924016 AUD Australia NATAAU3303M National Australia Bank Ltd Melbourne 1803114456500 RBOSNL2RTCM BBD BARBADOS BNBABBBB Republic Bank (Barbados) Ltd 028042192003 RBOSNL2RTCM 1030028017 BGN BULGARIA RZBBBGSF Raiffesen Bank AD Sofia RBOSNL2RTCM IBAN - BG55RZBB91551030028017 0099637057 BHD BAHRAIN NBOBBHBM National Bank of Bahrain RBOSNL2RTCM IBAN - BH94NBOB00000099637057 BMD Bermuda BNTBBMHM Bank of NT Butterfield & Son Hamilton 0601664670019 RBOSNL2RTCM CAD CANADA ROYCCAT2 Royal Bank of Canada Toronto 095911005743 RBOSNL2RTCM 02300000061046050000B CHF Switzerland UBSWCHZH80A UBS AG, Zurich RBOSNL2RTCM IBAN - CH140023023006104605B Care should be taken as this relates to CNH/CNY trading and settling offshore in CNY Hong Kong SCBLHKHH 44700867654 RBOSNL2RTCM Hong Kong with Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Ltd 266310663 CZK CZECH REPUBLIC CEKOCZPP Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka -

Big Reports.Pub

Page 1 U.S. Top Tier Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) as of December 31, 2010 Total Assets and Number of Institutions by Federal Reserve District Total Assets in $Billions No. of Institutions $10,000 1,000 $8,000 800 $6,000 600 $4,000 400 $2,000 200 $0 0 Bos NY Phil Clev Rich Atl Chi StL Minn KC Dal SF Total Consolidated Assets: $16,737 Total No. of Institutions: 4,787 Total Assets of U.S. Top Tier BHCs Total Assets of Seventh District Top Tier BHCs Bank of America HSBC North America All Other U.S. All Other Seventh BHCs JPMorgan Chase District BHCs Citigroup Ally Discover Goldman Sachs Wells Fargo Harris Northern Trust U.S. Top Tier BHCs Total Assets* District Seventh District Top Tier BHCs Total Assets* U.S. Rank Bank of America Corporation $ 2 ,268 14% Richmond HSBC North America Holdings Inc. $ 3 44 30% 9 JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2,118 13 New York Ally Financial Inc. 172 15 16 Citigroup Inc. 1,914 11 New York Northern Trust Corporation 84 7 25 Wells Fargo & Company 1,258 8 San Francisco Harris Financial Corp. 70 6 28 The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. 911 5 New York Discover Financial Services 64 6 30 Top 5 Subtotal 8,469 51 Top 5 Subtotal 734 64 All Other U.S. BHCs 8,268 49 All Other Seventh District BHCs 421 36 Total 16,737 100 Total 1,155 100 Source of Data: FR Y-9C Consolidated Financial Statements for Bank Holding Companies *Total Assets in $Billions; data generated February 24, 2011 FR Y-9SP Parent Company Only Financial Statements for Small Bank Holding Companies Components may not add to totals due to rounding Page 2 U.S. -

List of Market Makers and Authorised Primary Dealers Who Are Using the Exemption Under the Regulation on Short Selling and Credit Default Swaps

Last update 11 August 2021 List of market makers and authorised primary dealers who are using the exemption under the Regulation on short selling and credit default swaps According to Article 17(13) of Regulation (EU) No 236/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2012 on short selling and certain aspects of credit default swaps (the SSR), ESMA shall publish and keep up to date on its website a list of market makers and authorised primary dealers who are using the exemption under the Short Selling Regulation (SSR). The data provided in this list have been compiled from notifications of Member States’ competent authorities to ESMA under Article 17(12) of the SSR. Among the EEA countries, the SSR is applicable in Norway as of 1 January 2017. It will be applicable in the other EEA countries (Iceland and Liechtenstein) upon implementation of the Regulation under the EEA agreement. Austria Italy Belgium Latvia Bulgaria Lithuania Croatia Luxembourg Cyprus Malta Czech Republic The Netherlands Denmark Norway Estonia Poland Finland Portugal France Romania Germany Slovakia Greece Slovenia Hungary Spain Ireland Sweden Last update 11 August 2021 Austria Market makers Name of the notifying Name of the informing CA: ID code* (e.g. BIC): person: FMA ERSTE GROUP BANK AG GIBAATWW FMA OBERBANK AG OBKLAT2L FMA RAIFFEISEN CENTROBANK AG CENBATWW Authorised primary dealers Name of the informing CA: Name of the notifying person: ID code* (e.g. BIC): FMA BARCLAYS BANK PLC BARCGB22 BAWAG P.S.K. BANK FÜR ARBEIT UND WIRTSCHAFT FMA BAWAATWW UND ÖSTERREICHISCHE POSTSPARKASSE AG FMA BNP PARIBAS S.A. -

Numerical.Pdf

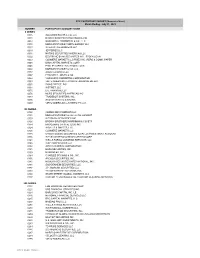

DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Numerical Sort ) Month Ending - July 31, 2021 NUMBER PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME 0 SERIES 0005 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO. LLC 0010 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO. 0013 SANFORD C. BERNSTEIN & CO., LLC 0015 MORGAN STANLEY SMITH BARNEY LLC 0017 INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC 0019 JEFFERIES LLC 0031 NATIXIS SECURITIES AMERICAS LLC 0032 DEUTSCHE BANK SECURITIES INC.- STOCK LOAN 0033 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC/FIXED INC. REPO & COMM. PAPER 0045 BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP. 0046 PHILLIP CAPITAL INC./STOCK LOAN 0050 MORGAN STANLEY & CO. LLC 0052 AXOS CLEARING LLC 0057 EDWARD D. JONES & CO. 0062 VANGUARD MARKETING CORPORATION 0063 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU FINANCIAL BD LLC 0065 ZIONS DIRECT, INC. 0067 INSTINET, LLC 0075 LPL FINANCIAL LLC 0076 MUFG SECURITIES AMERICAS INC. 0083 TRADEBOT SYSTEMS, INC. 0096 SCOTIA CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0099 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU ITG LLC 100 SERIES 0100 COWEN AND COMPANY LLC 0101 MORGAN STANLEY & CO LLC/SL CONDUIT 0103 WEDBUSH SECURITIES INC. 0109 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO./ETF 0114 MACQUARIE CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0124 INGALLS & SNYDER, LLC 0126 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC 0135 CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC/INVESTMENT ACCOUNT 0136 INTESA SANPAOLO IMI SECURITIES CORP. 0141 WELLS FARGO CLEARING SERVICES, LLC 0148 ICAP CORPORATES LLC 0158 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION 0161 BOFA SECURITIES, INC. 0163 NASDAQ BX, INC. 0164 CHARLES SCHWAB & CO., INC. 0166 ARCOLA SECURITIES, INC. 0180 NOMURA SECURITIES INTERNATIONAL, INC. 0181 GUGGENHEIM SECURITIES, LLC 0187 J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES LLC 0188 TD AMERITRADE CLEARING, INC. 0189 STATE STREET GLOBAL MARKETS, LLC 0197 CANTOR FITZGERALD & CO. / CANTOR CLEARING SERVICES 200 SERIES 0202 FHN FINANCIAL SECURITIES CORP. 0221 UBS FINANCIAL SERVICES INC. -

Citibank Europe Plc, Luxembourg Branch: List of Sub-Custodians

Citibank Europe plc, Luxembourg Branch: List of Sub-Custodians Country Sub-Custodian Argentina The Branch of Citibank, N.A. in the Republic of Argentina Australia Citigroup Pty. Limited Austria Citibank Europe plc, Dublin Bahrain Citibank, N.A., Bahrain Bangladesh Citibank, N.A., Bangaldesh Belgium Citibank Europe plc, UK Branch Benin Standard Chartered Bank Cote d'Ivoire Bermuda The Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited acting through its agent, HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited Bosnia-Herzegovina (Sarajevo) UniCredit Bank d.d. Bosnia-Herzegovina: Srpska (Banja Luka) UniCredit Bank d.d. Botswana Standard Chartered Bank of Botswana Limited Brazil Citibank, N.A., Brazilian Branch Bulgaria Citibank Europe plc, Bulgaria Branch Burkina Faso Standard Chartered Bank Cote D'ivoire Canada Citibank Canada Chile Banco de Chile China B Shanghai Citibank, N.A., Hong Kong Branch (For China B shares) China B Shenzhen Citibank, N.A., Hong Kong Branch (For China B shares) China A Shares Citibank China Co ltd ( China A shares) China Hong Kong Stock Connect Citibank, N.A., Hong Kong Branch Clearstream ICSD ICSD Colombia Cititrust Colombia S.A. Sociedad Fiduciaria Costa Rica Banco Nacioanal de Costa Rica Croatia Privedna banka Zagreb d.d. Cyprus Citibank Europe plc, Greece Branch Czech Republic Citibank Europe plc, organizacni slozka Denmark Citibank Europe plc, Dublin Egypt Citibank, N.A., Cairo Branch Estonia Swedbank AS Euroclear ICSD 1 Citibank Europe plc, Luxembourg Branch: List of Sub-Custodians Country Sub-Custodian Finland Nordea Bank AB (publ), Finish Branch France Citibank Europe plc, UK Branch Georgia JSC Bank of Georgia Germany Citibank Europe plc, Dublin Ghana Standard Chartered Bank of Ghana Limited Greece Citibank Europe plc, Greece Branch Guinea Bissau Standard Chartered Bank Cote D'ivoire Hong Kong Citibank NA Hong Kong Hungary Citibank Europe plc Hungarian Branch Office Iceland Citibank is a direct member of Clearstream Banking, which is an ICSD.