The Lay of the Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 Annual Report.Qxp

Annual Report E ATTORN H EY T F G O E N E E C R I F A F L Lisa Madigan O Illinois Attorney General S T A IS TE O OF ILLIN Table of Contents ABOUT US .........................................1 BIOGRAPHY .......................................2 PROTECTING CONSUMERS .........................4 Consumer Fraud Efforts Legislative Initiatives Health Care Assistance Public Utilities Antitrust & Non-Antitrust Settlements Protecting Businesses Building Better Charities KEEPING COMMUNITIES SAFE ......................16 Sex Offender Legislation Sex Offender Registry Sex Offender Enforcement Actions Sexually Violent Persons Enforcement Criminal Prosecutions & Trial Assistance Financial Crimes Criminal Revenue Prosecutions Unit High Tech Crimes Prosecuting Medicaid Fraud Statewide Grand Jury Prosecutions CURBING THE USE OF METHAMPHETAMINE ........24 Legislation Public Awareness ADVOCATING FOR WOMEN AND CHILDREN .........25 Short Form Order of Protection Domestic Violence Information Tear Sheets HELPING CRIME VICTIMS ...........................26 Illinois Crime Victims Compensation Program Violent Crime Victims Assistance Program (VCVA) Automated Victim Notification Program (AVN) Illinois Victim Assistance Academy (IVAA) Illinois Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (IL SANE) Program Statewide Victim Assistance Program Office of the Illinois Attorney General ADVOCATING FOR OLDER CITIZENS ............... 30 Advisory Council on Older Citizens' Issues Elderly Service Officer Training and Officer of the Year Award Senior Sleuths and Senior Medicare Patrols (SMPs) -

Municipalities with TIF Districts

Municipalities With TIF Districts As of 7/20/2021 Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Addison Village 022/010/32 Town Center Active Dupage Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Aledo City 066/010/30 TIF 1 Active Mercer Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Alexis Village 094/010/32 TIF 1 Active Warren Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Algonquin Village 063/010/32 Downtown TIF Active Mchenry Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Alorton Village 088/010/32 TIF 1 Active St. Clair Page 1 of 141 Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Alsip Village 016/010/32 123rd Place and Cicero Ave. Active Cook NW Corner of Cicero Avenue and I-294 Active Cook Pulaski Road Corridor Active Cook TIF 1 2016-12-31 Cook Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Altamont City 025/010/30 Altamont TIF Active Effingham Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Alton City 057/015/30 Hunterstown Active Madison Riverfront Active Madison Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Andalusia Village 081/010/32 1st Street and 6 th Avenue Active Rock Island Andalusia Road Active Rock Island Page 2 of 141 Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Annawan Village 037/020/32 I 80 and Downtown Active Henry US Rt. 6/ E. 2900 St. Active Henry Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Antioch Village 049/010/32 Antioch Corporate Center Active Lake Route 83 Redevelopment Active Lake Unit Name Code TIF District Terminated Date County Arcola City 021/010/30 -

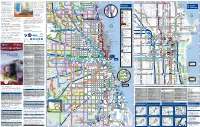

Chicago Downtown Chicago Connections

Stone Scott Regional Transportation 1 2 3 4 5Sheridan 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dr 270 ter ss C en 619 421 Edens Plaza 213 Division Division ne 272 Lake Authority i ood s 422 Sk 422 u D 423 LaSalle B w 423 Clark/Division e Forest y okie Rd Central 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie 422 The Regional Transportation Authority r P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware 620 421 0 E/W eehan Preserve Wilmette C Union Pacific/North Line 3rd 143 l Forest Baha’i Temple F e La Elm ollw Green Bay a D vice 4th v Green Glenview Glenview to Waukegan, Kenosha and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T i lo 210 626 Evanston Elm n (RTA) provides financial oversight, Preserve bard Linden nonstop between Michigan/Delaware e Dewes b 421 146 s Wilmette 221 Dear Milw Foster and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) funding, and regional transit planning R Glenview Rd 94 Hi 422 221 i i-State 270 Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Rand v r Emerson Chicago Downtown Central auk T 70 e Oakton National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Map Legend Hill 147 r Cook Co 213 and Marine/Foster (5200N) for the three public transit operations Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central Courts k Central 213 93 Maple College 201 Sheridan nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Holy 422 S 148 Old Orchard Gross 206 C Northwestern Univ Hobbie and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) Dee Family yman 270 Point Central St/ CTA Trains Hooker Wendell 22 70 36 Bellevue L in Northeastern Illinois: The Chicago olf Cr Chicago A Harrison 54A 201 Evanston 206 A 8 A W Sheridan Medical 272 egan osby Maple th Central Ser 423 201 k Illinois Center 412 GOLF Westfield Noyes Blue Line Haines Transit Authority (CTA), Metra and Antioch Golf Glen Holocaust 37 208 au 234 D Golf Old Orchard Benson Between O’Hare Airport, Downtown Newberry Oak W Museum Nor to Golf Golf Golf Simpson EVANSTON Oak Research Sherman & Forest Park Oak Pace Suburban bus. -

RTA Spanish System Map.Pdf

Stone Amtrak brinda servicios ferroviarios 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scott 13 14 Regional Transportation Sheridan r LaSalle desde Chicago Union Station a las er D 270 s C ent 421 Division Division Authority es 619 272 Edens Plaza Lake 213 sin ood u D 423 422 422 ciudades a través de Illinois y de los w B Clark/Division La Autoridad Regional de Transporte e Forest y Central 423 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie n r 422 800W 600W 200W 0 E/W P w GLENVIEW sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware Estados Unidos. Muchas de estas Preserve 620 C 421Union Pacific/North Line3rd 143 eeha l Forest Wilmette e La Baha’i Temple Elm F oll a D Green Bay 4th Green (RTA) se ocupa de la supervisión Antioch hasta v Glenview y Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T Glenview hasta Waukegan, Kenosha i Elm lo n r 210 Preserve 626 bard Linden Evanston sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware rutas, combinadas con autobuses de e Dewes b 421 146 financiera, del financiamiento y s Dea Mil Wilmette Foster 221 vice y Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) R Glenview Rd 94 Hi w 422 Thruway, están conectadas con 35 i i-State Chicago Cedar El Centro 221 Rand v r 270 au Emerson sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware Oakton T Central Hill de la planificación del transporte e National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena 70 147 r k Cook Co y Marine/Foster (5200N) ciudades de Illinois. Para obtener Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central 213 Courts k Central 213 Maple 93 Sheridan sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware regional para las tres operaciones de College S Presence 422 Gross 201 Hobbie 148 206 C Hooker y Marine/Irving -

Metabolizing Obsolescence: Strategies for the Dead Mall

METABOLIZING OBSOLESCENCE: STRATEGIES FOR THE DEAD MALL BY LAURA A. SCHATZMAN THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in Landscape Architecture in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Assistant Professor Richard L. Hindle, Chair Assistant Professor Gale Fulton Fabrication Coordinator Przemyslaw Swiatek ABSTRACT Landscapes evolve and adapt; yet obsolescence is a unique condition. Obsolescence occurs when such spaces are not used as was originally intended but still maintain some of the original qualities and characteristics. Obsolescence is partially viewed as a tangible repository of memories over time. It is time that creates change and causes obsolescence, thus such landscapes are always short-term even though they might have been designed for permanence. Although such areas may be viewed as blight upon the landscape, they can be potential prospects for repurposing. Certain factors can contribute to obsolescence in landscapes. Examining obsolete landscapes and those design strategies which leading to effective revitalization sheds light upon opportunities presented by dead malls in the American landscape. The Lincoln Square Mall of Urbana, Illinois, is analyzed as a case study to determine how obsolescence occurred and what strategies were effective for re- gaining vitality. This thesis utilizes the concepts of landscape architecture to formulate additional strategies and proposes one of these strategies to be used for the Lincoln Square Mall’s transformation. The strategies described are intended to improve site functionality, stimulate community development, and create value in landscape voids left by obsolescence. Furthermore since such areas are common, this thesis provides a methodology for design strategy development. -

System Includes 145 Stations, of Which 102 Touhy Northwest290 Hwy 290 290 157 Mannheim Ri Cald 22 Dee

Stone Amtrak provides rail service 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scott 13 14 Regional Transportation Sheridan LaSalle r Dr 270 from Chicago’s Union Station s C ente 421 Authority es 619 272 Edens Plaza Lake 213 Division Division sin ood u D 423 422 422 B w Antioch Clark/Division to cities throughout Illinois y Central 423 e Forest 151 a WILMETTE The Regional Transportation amie ville s n r 422 w P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W 0 E/W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware to Preserve 620 C 421Union Pacific/North Line3rd eeha l Forest Wilmette e La Baha’i Temple 143 F oll and United States. Many a D Green Bay Elm 4th v Green Glenview and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T Glenview i Authority (RTA) provides lo Elm n r 210 Preserve 626 to Waukegan, Kenosha bard Linden Evanston e nonstop between Michigan/Delaware vice Dewes b 421 of these routes, combined with s Dea Mil Wilmette Foster 146 221 Hi and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) financial oversight, funding, and R Glenview Rd 94 w 422 i i-State Chicago Downtown 221 Rand v r 270 au Emerson Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Oakton T Central Thruway buses, e National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Hill 70 147 regional transit planning for the r k Cook Co and Marine/Foster (5200N) Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central 213 Courts k Central 213 93 Sheridan Maple nonstop between Delaware/Michigan College S connect 35 Illinois cities. Presence 422 Gross 206 201 C Hobbie 148 Dee three public transit operations in yman 270 Huber Old Orchard Point Central St/ Northwestern Univ Hooker Bellevue and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) -

Green Power – Campaign to Fight Retail Redlining Matteson, Ill

Green Power – Campaign to Fight Retail Redlining Matteson, Ill. ICMA Best Practices 2004 April 22-23 2004 Annapolis/Anne Arundel County, Maryland Presenters: Name: David A. Mekarski,AICP Name: Rives Castleman Title Village Administrator Title Developer/Attorney Company: Village of Matteson Company: Realty America Group Street Address: 4900 Village Commons Street Address: 4809 Cole Ave., Ste. #200 City, State ZIP: Matteson, IL 60443 City, State ZIP: Dallas, TX 75205 Phone: 708-283-4949 Phone: 214-522-3300 x14 Fax: 708-283-4729 Fax: 214-522-0303 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Name: Hildy L. Kingma, AICP Title Director of Community Name: Robert D.Nadler Development/Deputy Administrator Title President/Midwest Region Company: Village of Matteson Company: Kimco Realty Corporation Street Address: 4900 Village Commons Street Address: 10600 W. Higgins Rd., Ste., #408 City, State ZIP: Matteson, IL 60443 City, State ZIP: Rosemont, IL 60018 Phone: 708-283-4940 Phone: 847-299-1160 Fax: 708-283-4952 Fax: 847-299-1167 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Name: Andre’ B. Ashmore Title Village Trustee Company: Village of Matteson Facilitator: Street Address: 4900 Village Commons City, State ZIP: Matteson, IL 60443 Name: Michelle L. Ferguson Phone: 708-283-4949 Title Assistant County Manager Fax: 708-283-4729 Company: Arlington County E-mail: [email protected] Street Address: 2100 Clarendon Blvd Ste 302 City, State ZIP: Arlington, VA 22201-5445 Phone: 703-228-3911 Fax: 703-228-3295 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Green Power – Campaign to Fight Retail Redlining Matteson, Ill. -

Batavia Division Overview Batavia Division

Batavia Division Overview Batavia Division Batavia Division operates bus routes in and around affluent areas of DuPage County that includes such communities as Addison, Carol Stream, Downers Grove, Glen Ellyn, Oak Brook, and Wheaton. Buses from Batavia Division have connections with bus routes from Pace’s Fox Valley, West and Westmont Divisions. 2 Batavia Division The communities covered by Batavia Division feature beautiful parks and nature areas, rich historic sites and museums as well as a wide variety of shopping, dining and entertainment. The area’s business sector ranges from small and mid-sized to Fortune 500. Available Media Interior Cards Fullbacks Brand Buses Fullwraps Kings Ultra Super Kings Queens Window Clings Tails Headlights Headliners Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. Do not share Batavia Division Commuter Profile Gender Age Female 53..8% 18-24 7.7% Male 46.2% 25-44 39.7% 45-64 37.1% Employment Status 65+ 15.5% Residence Status Full-Time 41.6% White Collar 51.6% Own 65.4% 0 25 50 Management, Business Financial 13.3% Rent 26.8% HHI Professional 19.8% Neither 7.8% Service 11.3% <$25k 7.4% Sales, Office 18.5% Race/Ethnicity $25-$34 9.8% White 80.1% Education Level Attained $35-$49 20.6% African American 4.5% High School 23.1% Hispanic 22.4% $50-$74 7.9% Some College (1-3 years) 31.2% Asian 8.9% >$75k 54.5% College Graduate or more 37.3% Other 6.5% 0 25 50 Source: Scarborough Chicago; Census Estimates Routes # Route Name # Route Name 674 Southwest Lombard 711 Wheaton-Addison 709 Carol Stream-North Wheaton 715 Central DuPage Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. -

IKE DISASTER RECOVERY IL QTRLY PERFORMANCE REPORT 2010-07-01 00:00:00.0 Thru 2010-09-30 23:59:59.0 Performance Report

IKE DISASTER RECOVERY IL QTRLY PERFORMANCE REPORT 2010-07-01 00:00:00.0 thru 2010-09-30 23:59:59.0 Performance Report Grant Number: B-08-DI-17-0001 Obligation Date: Grantee Name: State of Illinois Award Date: Grant Amount: 169191249 Contract End Date: Grant Status: Active Reviewed By HUD: Original - In Progress QPR Contact: No QPR Contact Found Disasters: Declaration Number Disaster Damage: The statewide average precipitation in 2008 was 50.7 inches, 11.4 inches above normal and the second wettest year since 1895. Based on preliminary data, the statewide average precipitation for September 2008 was 7.98 inches, making this the third wettest September on record (going back to 1895) for Illinois. Chicago (at O'Hare airport) reported 6.64 inches on September 13, 2008 setting a new record for the most rain in one calendar day in Chicago's history. Major flooding in three regions of the state kept the State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC) activated for more than three weeks in June and early July. A large contingent of state resources, including more than 1,400 Illinois National Guard troops, was activated to help communities along the Mississippi River and other rivers in northern and southeastern Illinois battle floodwaters. In total, 26 levees overtopped or breached along the Mississippi River between Rock Island, Illinois and St. Louis, Missouri. Six of the 26 overtopped or breached levee systems are located in Illinois. As a result of the June 2008 flooding, 25 Illinois counties were declared federal disaster areas per FEMA-1771-DR. Twenty-one of these 25 counties are located along the Mississippi, Embarras, and Wabash Rivers. -

Winter 2003.Indd

CENTER E FO WINTER H R T 2003 L A N N O THE LAY OF THE LAND I D THE CENTER FOR LAND USE INTERPRETATION NEWSLETTER T U A S T E RE INTERP The sites show the effect of time, sort of a sinking into timelessness. When I get to a site that strikes the kind of timeless chord, I use it. The site selection is by chance. There is ➣ no willful choice. A site at zero degree, where the material strikes the mind, where absences become apparent, appeals to me, where the disintegrating of space and time seems very apparent. Sort of an end of selfhood…the ego vanishes for awhile. -Robert Smithson, on site selection MARGINS IN OUR MIDST: FARM ANIMALS VIEW OF FARM DISPLAYED A JOURNEY INTO IRWINDALE IN THE EXHIBIT “LIVE STOCK FOOTAGE BY LIVESTOCK” THE CLUI CONDUCTS A PUBLIC TOUR OF THE PITS The pits of Irwindale are dramatic landscapes of extraction, operating out of view, beneath “On the Farm” exhibit at the CLUI, Los Angeles. CLUI photo the horizon line. The Durbin Pit, a dredge operation pulling gravel out from below the water table, was the first stop on the tour. CLUI photo IN AN EXHIBIT AT the CLUI, Los Angeles, called On the Farm: Live Stock Footage by Livestock, farm animals showed us their point of view, ON SEPTEMBER 20TH, THE Center conducted a public bus tour of the through wireless video cameras installed temporarily on their head industrial city of Irwindale, east of Los Angeles, as part of the exhibit and necks by virtuoso animal and plant videographer Sam Easterson. -

The Blues Brothers (Film) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 21/05/2014

The Blues Brothers (film) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 21/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search The Blues Brothers (film) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation The Blues Brothers is a 1980 American musical Technicolor comedy The Blues Brothers Main page film directed by John Landis and starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd Contents as "Joliet" Jake and Elwood Blues, characters developed from "The Featured content Blues Brothers" musical sketch on the NBC variety series Saturday Current events Night Live. Random article Donate to Wikipedia It features musical numbers by rhythm and blues (R&B), soul, and blues Wikimedia Shop singers James Brown, Cab Calloway, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, and Interaction John Lee Hooker. The film is set in and around Chicago, Illinois, and Help features non-musical supporting performances by John Candy, Carrie About Wikipedia Fisher, Charles Napier, and Henry Gibson. Community portal Recent changes The story is a tale of redemption for paroled convict Jake and his Contact page brother Elwood, who take on "a mission from God" to save the Catholic orphanage in which they grew up from foreclosure. To do so, they must Tools What links here reunite their R&B band and organize a performance to earn $5,000 to Related changes pay the tax assessor. Along the way, they are targeted by a destructive Upload file "mystery woman", Neo-Nazis, and a country and western band—all Theatrical release poster Special pages while being relentlessly pursued by the police. Permanent link Directed by John Landis Page information Universal Studios, which had won the bidding war for the film, was Produced by Bernie Brillstein Data item hoping to take advantage of Belushi's popularity in the wake of George Folsey, Jr. -

Inventory and Vision Memorandum

Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i I. INTRODUCTION I-1 Transit-Oriented Development I-1 Plan Purpose and Process I-2 Recent City Efforts I-2 Key Planning Considerations I-3 A Vision for Downtown Harvey I-3 Study Area Boundary and Vicinity I-4 Organization of the Plan I-6 II. PLANNING CONTEXT AND OPPORTUNITIES II-1 Existing Conditions II-1 Public Transit Facilities and Services II-5 Access, Circulation and Parking II-7 Market-Based Redevelopment Potential II-8 Planning Opportunities II-10 III. FRAMEWORK PLANS AND RECOMMENDATIONS III-1 Future Land Use Framework III-1 Future Circulation and Streetscape Framework III-4 Urban Design III-7 Design Guidelines III-8 Streetscape and Other Public Improvements III-14 Redevelopment Opportunities III-21 IV. IMPLEMENTATION IV-1 Enhancement of Administrative and Institutional Support Structure IV-1 Project Priorities IV-5 High Priority Action Items IV-7 Ongoing Initiatives IV-9 Funding Sources IV-11 Conclusion IV-16 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Vicinity Map I-5 Figure 2: Existing Land Use II-2 Figure 3: Areas Subject to Change II-4 Figure 4: Existing Access and Circulation Network II-6 Figure 5: Planning Opportunities II-11 Figure 6: Future Land Use Framework III-2 Figure 7: Future Circulation and Streetscape Framework III-5 Figure 8: Screening and Greening Park Avenue III-18 Figure 9: Park Avenue Street Sections III-19 Figure 10: 154th Street and Broadway Avenue Street Sections III-20 Figure 11: Redevelopment Opportunity 1 III-22 Figure 12: Redevelopment Opportunity 2 III-23 Figure 13: Redevelopment Opportunity 3 III-24 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Downtown Harvey Redevelopment Potential II-9 Harvey Station Area Plan November 2005 Acknowledgements The Station Area Plan for the City of Harvey, Illinois, was prepared through the efforts of the City of Harvey, the Regional Transportation Authority, Metra, Pace and the project planning consultants, HNTB Corporation and Valerie S.