The Benefits of Guide Dog Ownership L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of a Puppy Walker

The role of a puppy walker Registered charity in England and Wales (209617) and in Scotland (SC038979) The role of a puppy walker Thank you for thinking about becoming a puppy walker for Guide Dogs. The information in this leaflet should give you a better understanding of what the job involves and help you with your decision. We are very happy to answer any questions you may have and can arrange for one of our Puppy Walking Supervisors to call you if you wish to discuss things further. Puppy walking is a crucial part of Guide Dogs’ work. Although done on a voluntary basis, it will take a lot of time, commitment and love from both you and your family. The end result, however, is a very special animal indeed. Developing the puppy As a prospective puppy walker, who will care for and develop one of our puppies, it is essential that you consider the following criteria and questions: Essential criteria for puppy walking A puppy needs to be welcomed into your home and understood by all the family. The puppy should be reared with the blend of affection, control and supervision normally given to a young child. As a prospective puppy walker, who will care for and walk one of our puppies, the following criteria are essential: • You must be at least 18 years of age to be responsible for the puppy. Whilst any children at home can enjoy lending a hand, it is important that any puppy training, e.g. lead work, is only carried out by a responsible person. -

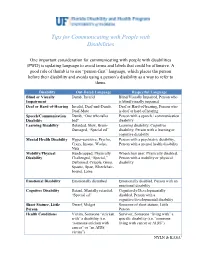

Tips for Communicating with People with Disabilities

Tips for Communicating with People with Disabilities One important consideration for communicating with people with disabilities (PWD) is updating language to avoid terms and labels that could be offensive. A good rule of thumb is to use “person-first” language, which places the person before their disability and avoids using a person’s disability as a way to refer to them. Disability Out-Dated Language Respectful Language Blind or Visually Dumb, Invalid Blind/Visually Impaired, Person who Impairment is blind/visually impaired Deaf or Hard-of-Hearing Invalid, Deaf-and-Dumb, Deaf or Hard-of-hearing, Person who Deaf-Mute is deaf or hard of hearing Speech/Communication Dumb, “One who talks Person with a speech / communication Disability bad" disability Learning Disability Retarded, Slow, Brain- Learning disability, Cognitive Damaged, “Special ed” disability, Person with a learning or cognitive disability Mental Health Disability Hyper-sensitive, Psycho, Person with a psychiatric disability, Crazy, Insane, Wacko, Person with a mental health disability Nuts Mobility/Physical Handicapped, Physically Wheelchair user, Physically disabled, Disability Challenged, “Special,” Person with a mobility or physical Deformed, Cripple, Gimp, disability Spastic, Spaz, Wheelchair- bound, Lame Emotional Disability Emotionally disturbed Emotionally disabled, Person with an emotional disability Cognitive Disability Retard, Mentally retarded, Cognitively/Developmentally “Special ed” disabled, Person with a cognitive/developmental disability Short Stature, Little Dwarf, Midget Someone of short stature, Little Person Person Health Conditions Victim, Someone “stricken Survivor, Someone “living with” a with” a disability (i.e. specific disability (i.e. “someone “someone stricken with living with cancer or AIDS”) cancer” or “an AIDS victim”) NYLN & KASA1 General Tips Use a normal volume and tone when speaking to persons with disabilities. -

Could a Dog Save Your Life?

Could DEVIN GRAyson’s WORLD WAS SHRINKING. The 36-year-old California a comic-book author and video game writer had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was 15, and like many people with insulin-dependent diabetes, she Dogsuffered wild swings in her blood glucose. Over time, she’d also de- veloped hypoglycemia unaware- ness, the inability to recognize symptoms of severe glucose lows. “One night I woke up and my ave blood sugar was 17,” she recalls. “It’s amazing I woke up at all and didn’t die in my sleep.” By the summer of 2005, Grayson was restricting her activi- ties because of her fear of hypo- S glycemic episodes. She gave up many of her favorite pursuits, like hiking in the redwoods north of San Francisco, and became reluc- tant to go out alone. She even moved into a house with friends because she worried that her dia- betes made it dangerous to live alone any longer. And still she felt trapped. “There’s a real psychic burden attached to diabetes,” she says. “You never get a break. (Your Life?) Every meal, every day, you have to monitor. It’s lonely. There are No one knows for sure how they do it, but a growing days when you would do anything number of canine companions are helping people with just to have a weekend off.” diabetes avoid dangerous hypoglycemia. Then Grayson met Cody, and everything changed. It was an By Amanda Spake Internet hook-up, of sorts: Online, Grayson had discovered Dogs for Diabetics, a Concord, Calif.–based organization that trains dogs to respond to serious blood glucose drops in humans. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Emotional Support Animal (ESA)

International Association of Canine Professionals Service Dog Committee HUD Assistance Animal and Emotional Support Animal definitions vs DOJ Service Dog (SD) Definition At this time, the IACP acknowledges the only country that we are aware of recognizing ESAs is the United States and therefore, the rules and regulations contained in this document are those of the United States. Service animals are defined as dogs (and sometimes miniature horses) individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual or other mental disability. The tasks may include pulling a wheelchair, retrieving dropped items, alerting a person to a sound, guiding a person who is visually impaired, warning and/or aiding the person prior to an imminent seizure, as well as calming or interrupting a behavior of a person who suffers from Post-Traumatic Stress. The tasks a service dog can perform are not limited to this list. However, the work or task a service dog does must be directly related to the person's disability and must be trained and not inherent. Service dogs may accompany persons with disabilities into places that the public normally goes, even if they have a “No Pets” policy. These areas include state and local government buildings, businesses open to the public, public transportation, and non-profit organizations open to the public. The law allowing public access for a person with a disability accompanied by a Service Dog is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) under the Department of Justice. Examples of Types of Service Dogs: · Guide Dog or Seeing Eye® Dog is a carefully trained dog that serves as a travel tool for persons who have severe visual impairments or are blind. -

Vehicle Acquisition

VEHICLE ACQUISITION F ederal Transit Administration Americans with Disabilities Act Circular C 4710.1 Draft Chapter for Public Comment October 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 THE DOT ADA REGULATIONS 1 1.2 PROVIDING SERVICE ON BEHALF OF ANOTHER ENTITY: “STAND IN THE SHOES” 1 2 ACQUISITION REQUIREMENTS FOR PUBLIC ENTITIES 3 2.1 BUSES AND VANS 4 2.2 RAPID RAIL AND LIGHT RAIL 5 2.3 COMMUTER RAIL 6 2.4 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS 7 2.5 DEMAND RESPONSIVE SERVICE 8 3 THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF ACCESSIBLE VEHICLES 10 3.1 BUSES AND VANS 13 3.2 RAPID RAIL VEHICLES 17 3.3 LIGHT RAIL VEHICLES 18 3.4 COMMUTER RAIL CARS 21 3.5 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS 23 4 ENSURING THAT VEHICLES ARE COMPLIANT 24 4.1 UNDERSTANDING THE SPECIFICATIONS 24 4.2 OBTAINING PUBLIC INPUT 24 4.3 ADDITIONAL SPECIFICATIONS 25 4.4 INSPECTIONS 25 5 DEFINITIONS 26 6 AUTHORITIES 28 7 REFERENCES 29 APPENDICES APPENDIX 1 SAMPLE BUS AND VAN SPECIFICATION CHECKLIST !"#$#%#$&'()*+,($$ -./')+.$#)0*'1'2'34$&/,52.($6$%(,72$ 8)239.($:;<:$ =,>.$<$37$:? ! 1 INTRODUCTION This Circular chapter on vehicle acquisition serves as a reference document for public transportation providers acquiring vehicles to ensure that these vehicles meet the requirements of the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) regulations. It is the goal of the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to help transportation providers meet their obligations under the ADA by outlining the regulations, describing effective practices, and presenting the information in an easy-to-use format. Please note that this Circular does not alter, amend, or otherwise affect the DOT ADA regulations themselves; transportation providers are advised to use this Circular in addition to (not in lieu of) the DOT ADA regulations. -

Battery Powered Wheelchair and Mobility Aid Guidance Document

Battery Powered Wheelchair and SafetyMobility requirements applicableAid toGuidance the carriage of battery powered Document wheelchairs and mobility aids when carried by passengers travelling by air Based on the 2019 Regulation compliance with the IATA Dangerous Goods Introduction Regulations. This document is based on the provisions set out in Passengers may only travel with a battery-powered the 2019-2020 Edition of the International Civil mobility aid with the airline’s approval. Proper pre- Aviation Organization (ICAO) Technical Instruction notification by the user helps to ensure that: for the Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air (Technical Instructions) and the 60th Edition of the ▪ all in the transportation chain know what IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR). device(s) and battery type(s) they are transporting; Information on the DGR can be found here: ▪ how to properly load and handle them; and https://www.iata.org/publications/dgr/Pages/index. ▪ what to do if an incident or accident occurs aspx either in-flight or on the ground. The batteries that power wheelchairs and mobility The pilot-in-command must be informed of the aids are considered dangerous goods when carried location of the mobility aid with installed batteries, by air. These and some other dangerous goods that removed batteries and spare batteries, to best deal are permitted for carriage by passengers can be with any emergencies that may occur. transported safely by air provided certain safety requirements are met. The requirements are Inadvertent operation of battery powered mobility detailed in the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations, aids can cause friction or electrical load which which are based on the ICAO Technical could lead to a fire. -

2017 Ada Update on Service Animal Rules

2017 ADA UPDATE ON SERVICE ANIMAL RULES The California Hotel & Lodging Association receives many questions regarding the rights and obligations of lodging establishments with respect to service animals. This document contains CHLA’s updated discussion of this topic. First, there has been a significant change regarding California law related to service animals. This change, which is discussed below, will make it easier for lodging operators to deal with guests who claim that their pets are service animals. Here are the basics of California law as it relates to service animals: • There was a time when the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing, which administers California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act (Act), took the position that the Act applied to the lodging industry. At that time, there was concern that lodging operators would have to comply with the more stringent requirements of the Act: (1) it is not limited to dogs— depending on the circumstances, the FEHA protects other types of animals and treats them as service animals; and (2) it provides protections for people who use “comfort” and “companion” animals. Contrary to the Department’s earlier position, however, CHLA was recently advised that the Act only applies to homes, condos, and apartments, and that it does not apply to hotels! • It is important for lodging operators to bear in mind that although the 2011 revisions to the ADA rules regarding service animals expressly state that (1) only dogs qualify as service animals,1 and that (2) “comfort” and “companion” dogs are not service animals,2 if a local jurisdiction in California has broader, more stringent rules than the ADA, the local rules must be complied with. -

First-Time Experience in Owning a Dog Guide by Older Adults with Vision Loss

Dominican Scholar Occupational Therapy | Faculty Scholarship Department of Occupational Therapy 8-12-2019 First-Time Experience in Owning a Dog Guide by Older Adults with Vision Loss Kitsum Li Department of Occupational Therapy, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Jeffrey Kou Department of Occupational Therapy, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Yvonne Lam Department of Occupational Therapy, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Patricia Lyons Department of Occupational Therapy, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Susan Nguyen Department of Occupational Therapy, Dominican University of California, [email protected] https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X19868351 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Li, Kitsum; Kou, Jeffrey; Lam, Yvonne; Lyons, Patricia; and Nguyen, Susan, "First-Time Experience in Owning a Dog Guide by Older Adults with Vision Loss" (2019). Occupational Therapy | Faculty Scholarship. 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X19868351 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Occupational Therapy at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occupational Therapy | Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: EXPERIENCES IN OWNING A DOG GUIDE First-Time Experience in Owning a Dog Guide Li, K., Kou, J., Lam, Y., Lyons, P., & Nguyen, S. Abstract Introduction: Dog guides were found to be effective in helping adults with vision loss navigate in the community and improve overall well-being. In spite of the vast amount of literature on pet therapy and dog companionship, limited study exists on older adult with vision loss experience of owning a dog guide. -

The Price of a Pedigree

The Price of a Pedigree DOG BREED STANDARDS AND BREED-RELATED ILLNESS The Price of a Pedigree: Dog breed standards and breed-related illness A report by Advocates for Animals 2006 Contents 1. Introduction: the welfare implications of pedigree dog breed standards 2. Current and future breeding trends 3. The prevalence of breed-related disease and abnormality 4. Breeds affected by hereditary hip and elbow dysplasia 4.1 The British Veterinary Association/Kennel Club hip and elbow dysplasia schemes 4.2 International studies of the prevalence of hip and elbow dysplasia 5. Breeds affected by inherited eye diseases 5.1 The British Veterinary Association/Kennel Club/ISDS Eye scheme 5.2 Further breed-related eye problems 6. Breeds affected by heart and respiratory disease 6.1 Brachycephalic Upper Airway Syndrome 6.2 Increased risk of heart conditions 7. Breed-related skin diseases 8. Inherited skeletal problems of small and long-backed breeds 8.1 Luxating patella 8.2 Intervertebral disc disease in chondrodystrophoid breeds 9. Bone tumours in large and giant dog breeds 10. Hereditary deafness 11. The Council of Europe and breed standards 11.1 Views of companion animal organisations on dog breeding 12. Conclusions and recommendations Appendix. Scientific assessments of the prevalence of breed-related disorders in pedigree dogs. Tables 1 – 9 and Glossaries of diseases References 1. Introduction: The welfare implications of pedigree dog breed standards ‘BREEDERS AND SCIENTISTS HAVE LONG BEEN AWARE THAT ALL IS NOT WELL IN THE WORLD OF COMPANION ANIMAL BREEDING.’ Animal Welfare, vol 8, 1999 1 There were an estimated 6.5 million dogs in the UK in 2003 and one in five of all households includes a dog.2 Only a minority (around a quarter) of these dogs are mongrels or mixed breed dogs. -

Relationship Between Body Image and Physical Functioning Following Rehabilitation for Lower-Limb Amputation

Western University Scholarship@Western Physical Therapy Publications Physical Therapy School 2019 Relationship between body image and physical functioning following rehabilitation for lower-limb amputation Jessica Desrochers Courtney Frengopoulos Michael W.C. Payne Ricardo Viana Susan W. Hunter Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/ptpub Part of the Physical Therapy Commons Relationship between body image and physical functioning following rehabilitation for lower limb amputation Jessica Desrochers BHSc1; Courtney Frengopoulos MSc2; Michael WC Payne MD3; Ricardo Viana MD3; Susan W Hunter PhD3,4 1. School of Health Studies, University of Western Ontario, London, ON; 2. Faculty of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, ON; 3. Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Western Ontario, London, ON; 4. School of Physical Therapy, University of Western Ontario, London, ON. Running title: Body image and mobility in lower extremity amputees Corresponding author: Dr. Susan W Hunter University of Western Ontario School of Physical Therapy Room 1588, Elborn College 1201 Western Road, London, Ontario Email: [email protected] Telephone: 519-661-2111 ext88845 Funding: This work was supported by the St. Joseph’s Foundation Cognitive Vitality and Brain Health Seed Funding Opportunity. The funding body had no involvement in the conduct of the study. Conflict of interest: None to report. Relationship between body image and physical functioning following rehabilitation for lower limb amputation ABSTRACT Objectives: To evaluate change in body image and the association between body image at discharge and mobility 4 months post rehabilitation. Methods: Prospective cohort of consecutive admissions to inpatient prosthetic rehabilitation. -

The Economics of Enhancing Accessibility Estimating the Benefits and Costs of Participation

The Economics of Enhancing Accessibility Estimating the Benefits and Costs of Participation Discussion01 Paper 2017 • 01 Bridget R.D. Burdett TDG Ltd, Hamilton, New Zealand Stuart M. Locke University of Waikato Management School, Hamilton, New Zealand Frank Scrimgeour Institute for Business Research, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand The Economics of Enhancing Accessibility Estimating the Benefits and Costs of Participation Discussion Paper No. 2017-01 Prepared for the Roundtable on Economics of Accessible Transport 3-4 March 2016, Paris Bridget R.D. Burdett TDG Ltd, Hamilton, New Zealand Stuart M. Locke Department of Finance, University of Waikato Management School, Hamilton, New Zealand Frank Scrimgeour Institute for Business Research, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand February 2017 The International Transport Forum The International Transport Forum is an intergovernmental organisation with 57 member countries. It acts as a think tank for transport policy and organises the Annual Summit of transport ministers. ITF is the only global body that covers all transport modes. The ITF is politically autonomous and administratively integrated with the OECD. The ITF works for transport policies that improve peoples’ lives. Our mission is to foster a deeper understanding of the role of transport in economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusion and to raise the public profile of transport policy. The ITF organises global dialogue for better transport. We act as a platform for discussion and pre- negotiation of policy issues across all transport modes. We analyse trends, share knowledge and promote exchange among transport decision-makers and civil society. The ITF’s Annual Summit is the world’s largest gathering of transport ministers and the leading global platform for dialogue on transport policy.