19Th-Century Familial Power Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hlocation of Legal Description

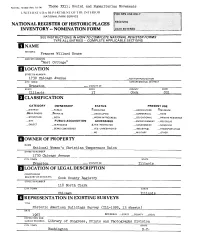

Form NO 10-300 (Rev 10-74) Theme XXI1; Social and Humanitarian Movements UNIT ED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Frances Willard House AND/OR COMMON "Rest Cottage" (LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 1730 Chicago Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Evans ton — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 17 Cook 031 HfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) J<PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -..COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER QJOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME National Woman's Christian Temperance Union STREET & NUMBER 1730 Chicago Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Evanston — VICINITY OF Illinois HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Cook County Registry STREET& NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY, TOWN STATE Ct|icaeo Illinois 3 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (ILL-1095, 13 sheets) DATE 1967 XFEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division " ~ " —--——————————————— CITY, TOWN Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE JfEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^-UNALTERED X—ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The home of Frances Willard and her family and the longtime headquarters of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union was built by her father, Josiah Willard in 1865 and added to in 1878. -

Frances Willard

Frances Willard sity, at that time an a, 1839-1898 Evanslon with her mott classes on rhetoric and c cial problems forced the Frances Willard was born in Churchville, New York, as one of three children of step to which Willard as~ Josiah and Mary Willard. She had an older brother, Oliver, and a younger sister, in charge of the womens Mary. Her father, a successful businessman and farmer and also a devout Unfortunately, just at Methodist, sold his assets in Churchville in 1841 and moved the family to Oberlin, supported Willard's effm Ohio, so that he could prepare for the ministry at Oberlin College. His wife, who ment, resigned and was had been a schoolteacher before her marriage, also attended classes (Oberlin was ancc. Although the two h the only co-educational college in the United States at that lime). But in 1846 Josiah Fowler immediately oppc Willard contracted tuberculosis, and on doctor's orders the family moved lo an iso thority through administr lated farm near Janesville, Wisconsin, where it was hoped the fresh air would help lhe male Northwes1cm stu him. lion at lhe school untenab l Frances and her siblings were home-schooled by their mother and occasional tu Willard now found her lors until 1854, when Oliver went to Beloit College to prepare for the ministry and offered lo her, but they w1 the girls attended a school in Janesville organized by their falher. In 1857 Frances move her elderly mother, and Mary enrolled in the Milwaukee Female College, a teacher-training institute hood of her many friends established by Catharine Beecher. -

Papers of Frances Willard.Docx

Frances E. Willard Memorial Library and Archives, Evanston, Illinois [email protected] Papers of Frances E. Willard, 1841-1991 Collection No. 2 Boxes 1-26 Biography Frances E. Willard (1839-1898) was arguably the most influential feminist of the 19th century and one of the generating influences in America’s long history of social justice reform. Born in New York in 1839, Willard moved to the Midwest early in her life, spending most of her childhood on the frontier in Wisconsin. She came to Evanston, Illinois, a suburb north of Chicago, to attend college in 1858, and called Evanston home for the rest of her life. Aware from a young age of the unequal status of women, Willard grew in her feminist outlook throughout her life. Starting out her career as a school teacher, and eventually rising to the prestigious position of Dean of Women at Northwestern University, Willard still sought a wider arena for working on what she called “the woman question.” The American temperance movement was gaining steam in the 1870s and women were showing a growing interest in temperance activism due to the overwhelming problem of alcohol for families. Per capita consumption of hard alcohol had increased dramatically during and after the Civil War, and access to clean water and other alternatives was limited. For women, the lack of legal rights made them and their children particularly vulnerable. Drunken husbands could drink away the family’s income or physically abuse them without any legal implications. Willard followed news of the women’s temperance crusades in the spring of 1874 and, when the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was organized later that year, she was elected Corresponding Secretary. -

Frances Willard's Pedagogical Ministry

THE IDEALLY ACTIVE: FRANCES WILLARD’S PEDAGOGICAL MINISTRY By Jane Robson Graham C2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas I partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Frank Farmer, Chair ___________________________ Amy J. Devitt ___________________________ J. Carol Mattingly ___________________________ Maryemma Graham ___________________________ Kristine Bruss Date Defended: _____________ ii The Dissertation Committee for Jane Robson Graham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE IDEALLY ACTIVE: FRANCES WILLARD’S PEDAGOGICAL MINISTRY Chairperson, Frank Farmer Amy J. Devitt J. Carol Mattingly Maryemma Graham Kristine Bruss Date Approved: _____________ iii Abstract This dissertation presents the teaching practices of temperance reformer Frances E. Willard. While Willard’s work in temperance reform has been well documented, the pedagogical aspect of her life has not. I argue that Willard’s form of rhetorical pedagogy enacted at two institutions—the Evanston College for Ladies and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union—retained the focus on creating a Christian citizen-orator often presented in histories as diminishing in importance in American educational institutions. Willard was positioned to continue this work despite its wane at the academy. She found that her form of pedagogy, which maintained an equilibrium between intellectual stimulation and ethical behavior, came into conflict with the late-nineteenth century academy’s emphasis on purely intellectual endeavor and professionalization. At the Evanston College for Ladies, which later became the Woman’s College at Northwestern University, Willard began a teaching practice that she later continued at the WCTU, an alternative educational institution. -

Hclassifi Cation Ulocation of Legal

Form NO 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) Theme XXI1; Social and Humanitarian Movements UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Frances Willard House AND/OR COMMON "Rest Cottage" 0LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 1730 Chicago Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Evanston — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 17 Cook 031 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) J<PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _ PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: QJOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME National Woman's Christian Temperance Union STREETS NUMBER 1730 Chicago Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Evanston — VICINITY OF Illinois ULOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Cook County Regi st ry STREET& NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY, TOWN STATE Qtp-caeo Illinois REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (ILL-1095, 13 sheets) DATE 1967 XFEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division CITY, TOWN "" STATE _________Washington______________________________B.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE JfEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The home of Frances Willard and her family and the longtime headquarters of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union was built "by her father, Josiah Willard in 1865 and added to in 1878.