The World After Brexit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call from Members of the Nizami Ganjavi International Centre to the United Nations Security Council to Support the UN Secretary

Call from Members of the Nizami Ganjavi International Centre to the United Nations Security Council to Support the UN Secretary-General’s Urgent Call for an Immediate Global Ceasefire amid the COVID-19 Pandemic We are deeply alarmed that the United Nations Security Council has not been able to reach agreement on a draft resolution put before it on COVID-19. This draft resolution called for an end to hostilities worldwide so that there could be a full focus on fighting the Covid-19 pandemic. If passed it would have given powerful backing to the call made earlier by the Secretary-General. Yet, agreement could not be reached on the resolution in the Security Council because of its reference to “the urgent need to support…. all relevant entities of the United Nations system, including specialized health agencies” in the fight against the pandemic. The failure to reach agreement saddens us at this time when our world is in crisis. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought about immense human suffering and is having a devastating impact on economies and societies. It is exactly at times like this that the leadership of the Security Council is needed. It should not be silent in the face of the serious threat to global peace and security which Covid-19 represents. Global action and partnership are vital now to deal with the global pandemic and its aftermath. This is the time for the premier institution responsible for leading on global security to show strength, not weakness. We support UN Secretary-General António Guterres in his call for an immediate global ceasefire, in all corners of the world, amid the COVID-19 pandemic. -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by Covid-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls – hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development – from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth – the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years. -

Page 1 of 3 Address Delivered by Her Excellency, Marie-Louise Coleiro

Page 1 of 3 Address delivered by Her Excellency, Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca, President of Malta, at the Parliament in Palermo, following the conferment of Honorary Membership to the Societa' Italiana di Storia della Medicina, 11 June 2018 Honourable Gianfranco Miccichè, President of the Sicilian Regional Assembly Honourable Members of the Sicilian Regional Assembly Distinguished guests Dear friends I feel truly honoured to be welcomed to the prestigious parliament of Palermo, which was once also historically, so connected to my country. I would like to show my deep appreciation to all of you for attending this memorable occasion. Be- ing a parliamentarian myself for many years, I know how much your time is precious, and hence, I really appreciate the time you are sparing to welcome me to your parliamentary chambers. I also feel a deep of sense of connection with all of you and all the people of Sicily. The Sicilians and the Maltese share the same sea, share the same climate, share the same challenges and share the same successes. This has been our story since our formation. Our history is interlinked. Our human stories have brought us many a time together. Above all, nature made us so near to each other, in a most geostrategic position in the midst of our Mediterranean Sea. Together we form this natural bridge that brings together two most important continents. Both of our countries played important roles in the history of the diverse civilisations and cultures which made the Mediterranean Sea such an enriched region in the world. At a time when unfortunately the world seems so uncertain, when many of us feel suspicious and wary of one another, we have a most important role to play. -

Carmelo Abela Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Promotion Malta

Carmelo Abela Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Promotion Malta A social democrat by conviction, Malta’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Promotion, Carmelo Abela (born 10th February 1972, Żejtun, Malta), is a strong believer in the capacity of the individual to make a positive difference. Standing out as a soft-spoken, driven politician, he has always led by example and conscientiously progressed through political circles. Before being first named to Cabinet, Mr Abela was employed with Mid-Med Bank Ltd, today HSBC Bank Malta plc, where he worked as a Manager. He was first elected to parliament in 1996, having served as a local councillor in his hometown of Żejtun, a city in the South Eastern Region of Malta, between 1994 and 1996. He has been returned to Parliament in all subsequent legislations. Over the years he has grown into increasingly senior roles within the Maltese Labour Party as well as Government, serving as Assistant Whip, Opposition Spokesperson for Youth and Sport and, later, Opposition Spokesperson for Education, Youth, Sport, and Culture. In 2008, he was unanimously appointed Deputy Speaker of the House of Representative as well as Opposition Main Spokesperson for Industry, Foreign Investment, and Social Policy. As a Member of Parliament, Mr Abela also served as Regional Representative on the Executive Committee of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Head of the Maltese Delegation of the Inter Parliamentary Union, and Member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Following his re-election in 2013, he was appointed Whip for the Government Parliamentary Group and, later, Government Spokesperson. -

Statement by H.E. Robert Abela, Prime Minister of Malta at the High

Statement by H.E. Robert Abela, Prime Minister of Malta at the High-level meeting to commemorate the seventy-fifth Anniversary of the United Nations Item 128(a) 21 September 2020 “The future we want, the United Nations we need: reaffirming our collective commitment to multilateralism” Secretary General, President of the General Assembly, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen It is highly significant that at the moment the world is gripped by a global pandemic, we come together through virtual means, to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the United Nations. In a matter of weeks, the pandemic manifested itself as the largest global challenge in the history of the United Nations. As the Final Declaration, which we endorse today, rightly states, ‘There is no other global organization with the legitimacy, convening power and normative impact as the United Nations. No other global organization gives hope to so many people for a better world and can deliver the future we want. The urgency for all countries to come together, to fulfill the promise of the nations united, has rarely been greater.’ Mr President, Today, the 21st September, Malta celebrates 56 years of Independence, but what is also noteworthy is that Malta became the 114th member of the United Nations Organisation on the 1st December 1964, only a few weeks after gaining Independence. On the raising of the flag the then Maltese Prime Minister, Dr George Borg Olivier, emphasized Malta’s position between East and West, Europe and Africa, and spoke of Malta’s aspirations for peaceful development. Now that Malta had taken her place among the free nations, the Prime Minister pledged Malta’s contribution towards world peace in that, ‘spirit of heroic determination, in defence of traditional concepts of freedom and civilisation’, which have characterized Malta’s long history. -

Letter to Robert ABELA, Prime Minister of Malta, on the Human

Ref: CommHR/DM/sf 013-2020 Mr Robert ABELA Prime Minister of Malta Strasbourg, 5 May 2020 Dear Prime Minister, As Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, I monitor member states’ observance of their human rights obligations towards migrants, including asylum seekers and refugees, who cross the Mediterranean in an attempt to reach Europe. I am writing to you in relation to various recent reports about Malta’s handling of the situation of migrants in distress at sea. I would like to recall Malta’s obligation under international maritime and human rights law to ensure that its authorities respond effectively and urgently to any situation of distress at sea of which they become aware. Obligations to coordinate search and rescue operations may also accrue when the distress situation occurs outside the Maltese Search and Rescue Region (SRR), at the very least until such moment when coordination can be handed over to other states’ authorities that are willing and able to assume responsibility in a manner compliant with maritime and human rights law, and have effectively done so. I therefore urge your government to ensure that Malta fully meets its obligations when it is notified of a distress situation or receives requests for assistance, and that all credible allegations of delay or non-response are investigated and addressed. I would also like to emphasise that prompt disembarkation in a place of safety is an integral part of states’ search and rescue obligations. It has been well documented that Libya, both on account of the ongoing conflict and the serious human rights violations that persons disembarked there face, cannot be considered a place of safety. -

A Review of the Constitution of Malta at Fifty: Rectification Or Redesign?

A REVIEW OF THE CONSTITUTION OF MALTA AT FIFTY: RECTIFICATION OR REDESIGN? A REVIEW OF THE CONSTITUTION OF MALTA AT FIFTY: RECTIFICATION OR REDESIGN? Report Published by The Today Public Policy Institute Lead Authors: Michael Frendo and Martin Scicluna Presented to the Prime Minister, September 2014 The Today Public Policy Institute is an autonomous, not-for-profit, non-governmental organisation. Its mission is to promote wide understanding of strategic issues of national importance and to help in the development and implementation of sound public policies. In pursuit of this mission, it sponsors or initiates research on specific national problems, encourages solutions to those problems and facilitates public debate on them. It is not affiliated to any political party or movement. Its Board is made up of the following individuals: Martin Scicluna (Director General), Michael Bonello, Sina Bugeja, Stephen Calleya, Juanito Camilleri, Petra Caruana Dingli, John Cassar White, George Debono, Mark Anthony Falzon, Michael Frendo, Martin Galea, Joseph Sammut, Joseph V. Tabone, Patrick Tabone, Clare Vassallo, John Vassallo and Joseph F.X. Zahra. Board members participate in The Today Public Policy Institute on a voluntary basis and in their personal capacity. Their association with the Institute and with the specific reports produced for the Institute by Lead Authors in the think-tank is without prejudice to the policies and positions of their respective institutions or organisations, nor does it necessarily imply the endorsement by each Board member of the conclusions and recommendations presented in such reports. This report reflects a set of ideas, options, approaches, conclusions and recommendations advanced by the Lead Author. -

Remarks by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker At

European Commission - Speech Remarks by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker at the joint press conference with Joseph Muscat, Prime Minister of Malta Valletta, 11 January 2017 Joseph, thank you. I am happy to be back in Malta. It is the sixth time I am visiting this marvellous country. I remember the second time before last time, I was campaigning in this country against the Socialists, against the Prime Minister – I won. You are a local winner, I am a global winner. But we have the best relations – professional and personal, personal relations between those being in charge of European affairs are more important than people normally think. And I have built with Joseph an excellent personal and professional relation. The professional part of this is as important as the other one, and we were preparing together the first Maltese Presidency. Malta has now been a member of the European Union for 13 years; it is the first time that Malta is in the chair of the Presidency. I had that chance – if it is a chance – four times in my life, and so I know how heavy the duties are. And we, as the Commission, have the impression and the knowledge indicating that the Maltese Government has prepared this Presidency in an excellent way. We noted that when the Prime Minister was visiting Brussels back in November last year, and we have seen today in our contacts with the Ministers in charge that Malta is best prepared for this Presidency. We are very much on the same line, swimming in the same channel, swimming in the same direction. -

Listofspeakers

GENERAL ASSEMBLY Special session of the General Assembly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (resolution 75/4) LIST OF SPEAKERS Thursday, 03 December 2020, 9:00 AM 1. His Excellency Filipe Jacinto NYUSI President of the Republic of Mozambique (on behalf of the Southern African Development Community) 2. His Excellency Charles MICHEL President of the European Council of the European Union 3. His Excellency Carlos ALVARADO QUESADA President of the Republic of Costa Rica 4. His Excellency Recep Tayyip ERDOĞAN President of the Republic of Turkey 5. His Highness Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad AL-THANI Emir of the State of Qatar 6. Her Excellency Simonetta SOMMARUGA President of the Swiss Confederation 7. His Excellency Juan Orlando HERNÁNDEZ ALVARADO President of the Republic of Honduras 8. His Excellency Ilham Heydar oglu ALIYEV President of the Republic of Azerbaijan 9. His Excellency Kais SAIED President of the Repubic of Tunisia 10. His Excellency Miguel Díaz-Canel BERMÚDEZ President of the Council of State and Ministers of the Republic of Cuba Page 1 of 15 23/11/2020 22:58:44 GENERAL ASSEMBLY Special session of the General Assembly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (resolution 75/4) LIST OF SPEAKERS Thursday, 03 December 2020, 9:00 AM 11. His Excellency Francisco Rafael SAGASTI HOCHHAUSLER President of the Republic of Peru 12. His Excellency Wavel RAMKALAWAN President of the Republic of Seychelles 13. His Excellency Muhammadu BUHARI President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 14. His Excellency Sebastián Piñera ECHEÑIQUE President of the Republic of Chile 15. His Excellency Luis Alberto ARCE CATACORA Constituional President of the Plurinational State of Bolivia 16. -

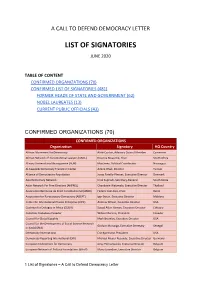

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

Gerald Strickland 1861-1940

PRIME MINISTERS OF MALTA - 4 GERALD STRICKLAND 1861-1940 PROFILE Gerald Strickland was born in Valletta on the 24 May 1861 to Walter and Louisa née Bonici Mompalao. Studying both in Malta and abroad, he graduated in law from Trinity College, Cambridge in 1887. In 1890, he married Edeline Sackville with whom he had eight children. After her death in 1918, he married Margaret Hulton on the 31 August 1926. On the 9 August 1927, he was appointed fourth Prime Minister of Malta, keeping office until the 21 June 1932. Lord Strickland passed away on 22 August 1940, aged 79, and was interred in the Cathedral at Mdina. POLITICS In the 1888 election, Strickland was elected to the Council of the Government of Malta, representing nobility and property owners. Shortly after, he was nominated and chosen as Chief Secretary by the Colonial Government. Between 1902 and 1917, Strickland served as governor in various states within the British Empire. In 1917, he returned to the local scene and founded the Anglo-Maltese Party. Soon after, the party merged with the Maltese Constitutional Party, under his leadership, as the Constitutional Party. Strickland was Opposition Leader from 1921 to 1927, as well as between July 1932 and November 1933. After the 1927 election, he became Prime Minister of Malta with a majority of seats in the Legislative Assembly, made possible following an agreement with the Labour Party, known as the Compact. A primary project which was initiated during his premiership was the construction of St Luke’s Hospital. The Constitutional Party lead by Strickland won six out of ten seats during the 1939 elections and he was thus appointed leader of the Council of the Government. -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by COVID-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls - hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development - from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth - the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years.