The Ecology and Social Behaviour of Chowchillas, Orthonyx Spaldingii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Type Specimens of Birds in the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren Revised Edition

Type Specimens of Birds in the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren Revised Edition Michel Louette, Danny Meirte, Annelies Louage and Alain Reygel Zoological Documentation Online Series TYPE SPECIMENS OF BIRDS IN THE ROYAL MUSEUM FOR CENTRAL AFRICA, TERVUREN Michel Louette Danny Meirte Annelies Louage and Alain Reygel Previously published in 2002 by the RMCA, in the series “Zoological Documentation”, vol. 26: Type Specimens in the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Louette, M., D. Meirte, A. Louage & A. Reygel). © Royal Museum for Central Africa, 2010 for this new edition 13, Leuvensesteenweg 3080 Tervuren, Belgium www.africamuseum.be All rights reserved. Any reproduction of this publication, except for private or educational use, by means of print, photocopy or any other medium is strictly prohibited without the written authorization of the RMCA’s Publications Service, Leuvensesteenweg 13, B-3080 Tervuren, Belgium. © 2010 Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Africa Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd door middel van druk, fotokopieën, geautomatiseerde gegevensbestanden of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van het Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Africa, Leuvensesteenweg 13, B-3080 Tervuren. © 2010 Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale. Toute reproduction de cette publication à fin autre que privée ou éducative, que ce soit par impression, photocopie ou tout autre moyen est interdite sans l’autorisation écrite préalable du Service des Publications du Musée royal de l’Afrique central, Leuvense- steenweg 13, B-3080 Tervuren, Belgique. ISBN 978-9-0747-5280-0 Legal Deposit: D/2010/0254/24 Cover : type specimens of Afropavo congensis Photo © RMCA CONTENTS KEY WORDS ....................................................................................................................... -

Supplementary Information For

Supplementary Information for Earth history and the passerine superradiation Oliveros, Carl H., Daniel J. Field, Daniel T. Ksepka, F. Keith Barker, Alexandre Aleixo, Michael J. Andersen, Per Alström, Brett W. Benz, Edward L. Braun, Michael J. Braun, Gustavo A. Bravo, Robb T. Brumfield, R. Terry Chesser, Santiago Claramunt, Joel Cracraft, Andrés M. Cuervo, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, Travis C. Glenn, Michael G. Harvey, Peter A. Hosner, Leo Joseph, Rebecca Kimball, Andrew L. Mack, Colin M. Miskelly, A. Townsend Peterson, Mark B. Robbins, Frederick H. Sheldon, Luís Fábio Silveira, Brian T. Smith, Noor D. White, Robert G. Moyle, Brant C. Faircloth Corresponding authors: Carl H. Oliveros, Email: [email protected] Brant C. Faircloth, Email: [email protected] This PDF file includes: Supplementary text Figs. S1 to S10 Table S1 to S3 References for SI reference citations Other supplementary materials for this manuscript include the following: Supplementary Files S1 to S3 1 www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1813206116 Supplementary Information Text Extended Materials and Methods Library preparation and sequencing. We extracted and purified DNA from fresh muscle tissue, liver tissue, or toepad clips from 113 vouchered museum specimens (Supplementary File S1) using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. We quantified DNA extracts using a Qubit fluorometer, and we prepared aliquots of DNA extracted from muscle and liver at 10 ng/µL in 60 µL volume for shearing. We sheared each DNA sample to 400–600 bp using a Qsonica Q800R sonicator for 15–45 cycles, with each cycle running for 20 seconds on and 20 seconds off at 25% amplitude. -

Characterization of Polymorphic Microsatellites in the Logrunner, Orthonyx Temminckii (Aves: Orthonychidae)

Molecular Ecology Notes (2007) 7, 1117–1119 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01798.x PRIMERBlackwell Publishing Ltd NOTE Characterization of polymorphic microsatellites in the logrunner, Orthonyx temminckii (Aves: Orthonychidae) JAMES A. NICHOLLS,*† JEREMY J. AUSTIN,*‡ DAVID C. PAVLACKY* and DAVID J. GREEN*§ *School of Integrative Biology, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia Abstract We isolated and characterized 10 polymorphic microsatellite loci in the logrunner (Orthonyx temminckii), a rainforest-dwelling Australian bird. The number of alleles per locus observed within two populations ranged from three to 39, with observed heterozygosities of between 0.12 and 1.00. We demonstrate that these markers are useful for both population- and individual-level analyses. Keywords: logrunner, microsatellite, Orthonychidae, Orthonyx, passerine Received 16 February 2007; revision accepted 23 March 2007 The logrunner (Orthonyx temminckii) is a medium-sized conducted following the protocol described in Frentiu (60 g) passerine endemic to southeastern Australia. It is et al. (2003). Fifteen unique cloned sequences were selected a ground-dwelling species, confined to rainforests and for further development. Primers located in the flanking fringing wetter eucalypt forests (Higgins & Peter 2002). regions around the repetitive element in each sequence Previous genetic work on this species has been restricted were designed using the program primer 3 (Rozen & to broad-scale analyses of mtDNA and nuclear intron Skaletsky 2000). Optimization of polymerase chain reaction variation examining phylogeographical patterns and (PCR) conditions and initial screening for polymorphism species boundaries (Joseph et al. 2001; Norman et al. 2002). was conducted using seven individuals from southeastern Given this species’ reliance upon rainforest habitats, its Queensland, with unlabelled PCR product sized on a status as a year-round resident and its limited dispersal Corbett Gelscan 2000 machine. -

Detertminants of Guild Structure in Forest Bird Communities; An

The Condor 88:421-439 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1986 DETERMINANTS OF GUILD STRUCTURE IN FOREST BIRD COMMUNITIES: AN INTERCONTINENTAL COMPARISON’ RICHARD T. HOLMES Department of BiologicalSciences, Dartmouth College,Hanover, NH 03755 HARRY F. RECHER Department of VertebrateEcology, Australian Museum, 6-8 CollegeStreet, Sydney,N.S. W. 2000, Australia Abstract. We examined the patterns of food resourceutilization (guild structure)of 4 1 species of birds that breed in eucalypt forestsand woodlands in south temperate Australia, and compared them to the results of a similar study in a north temperate, broad-leaved forest in North America (Holmes et al. 1979). Both studies used the same field methods and analytical techniques. The Australian community was more complex as inferred from the greater number of guilds (9 vs. 4) and from the results of principal components and factor analyses of the foraging data. These multivariate methods showed that guilds at the Australian site were separatedfirst by differences in foraging height and bird weight, and second by foraging methods and food substrates.Use of specific foraging substrates(e.g., exfoliating bark) and food resources(e.g., nectar and other car- bohydrates)were important at finer scalesof separation. The results support the hypothesisthat vegetationstructure and food availability, which vary with plant speciesand vertical strata,produce particular setsof foragingopportunities for birds. These in turn influence which speciescan obtain food successfully,and thus can be consideredprimary determinants of guild structure.This com- parison of food utilization patterns of birds in contrastinghabitats provides insight into the factors determining bird community organization. Key words: Australianforest birds;bird communityecology; birdforaging; community structure: foliage structure;guild structure;resource availability: resourcepartitioning. -

Earth History and the Passerine Superradiation

Earth history and the passerine superradiation Carl H. Oliverosa,1, Daniel J. Fieldb,c, Daniel T. Ksepkad, F. Keith Barkere,f, Alexandre Aleixog, Michael J. Andersenh,i, Per Alströmj,k,l, Brett W. Benzm,n,o, Edward L. Braunp, Michael J. Braunq,r, Gustavo A. Bravos,t,u, Robb T. Brumfielda,v, R. Terry Chesserw, Santiago Claramuntx,y, Joel Cracraftm, Andrés M. Cuervoz, Elizabeth P. Derryberryaa, Travis C. Glennbb, Michael G. Harveyaa, Peter A. Hosnerq,cc, Leo Josephdd, Rebecca T. Kimballp, Andrew L. Mackee, Colin M. Miskellyff, A. Townsend Petersongg, Mark B. Robbinsgg, Frederick H. Sheldona,v, Luís Fábio Silveirau, Brian Tilston Smithm, Noor D. Whiteq,r, Robert G. Moylegg, and Brant C. Fairclotha,v,1 aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803; bDepartment of Biology & Biochemistry, Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, Claverton Down, Bath BA2 7AY, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, United Kingdom; dBruce Museum, Greenwich, CT 06830; eDepartment of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN 55108; fBell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN 55108; gDepartment of Zoology, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, São Braz, 66040170 Belém, PA, Brazil; hDepartment of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; iMuseum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; jDepartment of Ecology and Genetics, Animal Ecology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, -

Earth History and the Passerine Superradiation

Earth history and the passerine superradiation Carl H. Oliverosa,1, Daniel J. Fieldb,c, Daniel T. Ksepkad, F. Keith Barkere,f, Alexandre Aleixog, Michael J. Andersenh,i, Per Alströmj,k,l, Brett W. Benzm,n,o, Edward L. Braunp, Michael J. Braunq,r, Gustavo A. Bravos,t,u, Robb T. Brumfielda,v, R. Terry Chesserw, Santiago Claramuntx,y, Joel Cracraftm, Andrés M. Cuervoz, Elizabeth P. Derryberryaa, Travis C. Glennbb, Michael G. Harveyaa, Peter A. Hosnerq,cc, Leo Josephdd, Rebecca T. Kimballp, Andrew L. Mackee, Colin M. Miskellyff, A. Townsend Petersongg, Mark B. Robbinsgg, Frederick H. Sheldona,v, Luís Fábio Silveirau, Brian Tilston Smithm, Noor D. Whiteq,r, Robert G. Moylegg, and Brant C. Fairclotha,v,1 aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803; bDepartment of Biology & Biochemistry, Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, Claverton Down, Bath BA2 7AY, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, United Kingdom; dBruce Museum, Greenwich, CT 06830; eDepartment of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN 55108; fBell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN 55108; gDepartment of Zoology, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, São Braz, 66040170 Belém, PA, Brazil; hDepartment of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; iMuseum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; jDepartment of Ecology and Genetics, Animal Ecology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, -

307 Lyall's Wren

Text and images extracted from Higgins, P.J .; Peter, J.M. & Steele, W.K. (editors) 2001 . Handbook of Australian , New Zealand & Antarctic Birds . Volume 5, Tyrant-flycatchers to chats . Melbourne, Oxford University Press. Pages 51-55, 58-59, 90-91. Reproduced with the permission of Bird life Australia. 51 Order PASSERIFORMES The largest and most diverse order of birds, commonly called passerines or perching birds, and comprising some 5 712 species in 45 families (based on Sibley &Monroe 1990; Sibley &Ahlquist 1990), and well over half the world's known bird species. In the HANZAB region, Passeriformes represented by some 382 species in 39 families. Tiny to large: smallest passerine is Pygmy Tit Psaltria exilis of Java, with a total length c. 8 em; largest is Greenland Raven Corvus corax principalis, with a total length c. 64 em and weighing up to 1. 7 kg. Superb Lyre bird Menura novaehollandiae of e. Aust. probably second largest in Order, with a total length (in adult male) of c. 103 em, including tail of c. 70 em, and weight up to c. 1.1 kg. Cosmopolitan except Antarctica and some oceanic islands; and occupying all terrestrial habitats. Overall, Passeriformes are characterized by (based on Raikow 1982; Sibley & Ahlquist 1990; and DAB [=Schodde & Mason 1999]): Palate aegithongnathous (except Conopophagidae [gnateaters]). Intestinal caeca rudimentary. Single left carotid artery (except paired in Pseudocalyptomena and possibly other broad bills [Eurylaimidae]). Aftershaft reduced or absent. Neck short, with 14 cervical vertebrae in most, but 15 in Eurylaimidae (broadbills); atlas perforated; metasternum usually two-notched (rarely four-notched). -

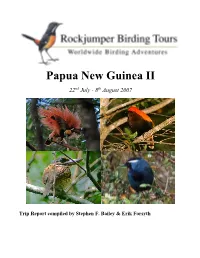

Papua New Guinea II

Papua New Guinea II 22nd July - 8th August 2007 Trip Report compiled by Stephen F. Bailey & Erik Forsyth RBT Papua New Guinea II July 2006 2 Top twelve birds of the trip as voted by the participants 1. Greater Bird-of-paradise 2. Southern Crowned-Pigeon 3. King-of-Saxony Bird-of-paradise 4(tie). King Bird-of-paradise 4(tie). Wallace’s Fairywren 6(tie). Crested Bird-of-paradise 6(tie). Greater Melampitta 8. Palm Cockatoo 9. Crested Berrypecker 10(tie). Brehm’s Tiger-Parrot 10(tie). Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia 10(tie). Blue Bird-of-paradise Tour Summary Our tour of Papua New Guinea began as we boarded our aircraft to the South Pacific islands of the Bismarck Archipelago for the pre-tour extension. First-off, we visited the rainforest of the Pokili Wildlife Management Area which holds the largest breeding colony of Melanesian Scrubfowl in the world. It was an amazing experience to wander through the massive colony of these bizarre birds. We also managed outstanding views of the gorgeous Black-headed Paradise-Kingfisher, Blue-eyed Cockatoo and Red- knobbed Imperial-Pigeon. Some participants were fortunate to spot the rare Black Honey Buzzard. Then we took time to explore several small, remote tropical islands in the Bismarck Sea and were rewarded with sightings of Black-naped Tern, the boldly attractive Beach Kingfisher, Mackinlay’s Cuckoo-Dove and the extraordinary shaggy Nicobar Pigeon. Back on the main island, we visited the Pacific Adventist University, where we found a roosting Papuan Frogmouth, White-headed Shelduck and Comb-crested Jacana. -

Passeriformes) and Their Zoogeographic Signal

Zootaxa 3786 (5): 501–522 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3786.5.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D2764982-F7D7-4922-BF3F-8314FE9FD869 Relicts from Tertiary Australasia: undescribed families and subfamilies of songbirds (Passeriformes) and their zoogeographic signal RICHARD SCHODDEI & LES CHRISTIDISJ IAustralian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, PO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia. E-mail: [email protected] J=National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University, Coffs Harbour, New South Wales 2450 Australia Abstract A number of hitherto unrecognized, deeply divergent taxa of Australasian songbirds have been revealed by DNA sequence studies in the last decade. Differentiation among them is at levels equivalent to family and subfamily rank among song- birds generally. Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to name and describe eleven of them formally under Articles 13.1, 13.2, 16.1 and 16.2 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature so that they are made available for use in zoology. The taxa are: families Oreoicidae, Eulacestomatidae, Rhagologidae, Ifritidae and Melampittidae, and subfamilies Pachycareinae, Oreoscopinae, Toxorhamphinae, Oedistomatinae, Peltopsinae and Lamproliinae. The families to which the subfamilies belong are documented. Morphological and behavioural traits of the new family-group taxa are discussed; reasons for taxonomic rankings are summarized; and grounds for the geographic origin of corvoid songbirds, to which all the new families belong, are briefly addressed. One new genus, Megalampitta in Melampittidae, is also described. Key words: taxonomy, nomenclature, songbirds, family-group taxa, New Guinea, Australia, zoogeography Introduction Over the last decade, DNA sequence technology has realigned much of the phylogeny and classification of Class Aves (birds). -

Grand Australia Part Ii: Queensland, Victoria & Plains-Wanderer

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART II: QUEENSLAND, VICTORIA & PLAINS-WANDERER OCTOBER 4–21, 2019 Australian Pratincole © Max Breckenridge LEADERS: MAX BRECKENRIDGE & KEVIN ZIMMER LIST COMPILED BY: MAX BRECKENRIDGE VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM VENT’s Grand Australia Tour has been a staple offering for almost two decades now, led by the insatiable Dion Hobcroft. Dion’s skills as a tour leader and his extensive knowledge of Australia, his home country, meant that the tour has grown immensely in popularity over the years. As such, in 2019, for the first time, VENT offered two subsequent trips for both Part I, Part II, and the extension to Tasmania. I was the primary leader for the first run of Grand Australia, with Dion to follow a week later (and David James in Tasmania). My co-leaders were the two Zimmer brothers, Kevin and Barry, who are two of VENT’s long-serving and most popular tour leaders. Barry joined me for Part I and Kevin was with me for three weeks during Part II and Tasmania. I learned a great deal from both and enjoyed their company immensely, making the whole five weeks of touring very enjoyable. Thanks are definitely in order to both Barry and Kevin, but also to Dion and David for their work in creating these tours. Of course, I must also thank Victor and Barry Lyon for their foresight and for putting their trust in me, as well as the office staff, in particular Erik and Rene, for making it all happen.