1930 - 1937 India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVERNMENT of MAHARASHTRA Department of Agriculture

By Post/Hand GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA Department of Agriculture To, M/s. VARAD FERTILIZERS, 114 Vasant Market Yard Sangli, Sangli Miraj Kupwad (m Corp.), Pin: 416416, Tahsil: Miraj, District: Sangli, State: Maharashtra Sub: Issuing New Fertiliser License No. LCFDW10010368. Validity: 09/04/2018 to 08/04/2021 Ref : Your letter no. FWD241514 dated : 25/12/2014 Sir, With reference to your application for New Fertilizer license. We are pleased to inform you that your request for the same has been granted. License No. : LCFDW10010368 dated :09/04/2018. Valid For : 09/04/2018 to 08/04/2021 is enclosed here with. This license is issued under Fertilizer Control Order,1985 The terms and conditions are mentioned in the license. You are requested to apply for the renewal of the license on or before 08/04/2021. Responsible Person Details: Name: Sainath Sudhakar Parsewar, Age:34, Designation: Partner Office Address: 114 Vasant Market Yard Sangli, Sangli Miraj Kupwad (M Corp.), Taluka:Miraj, District: Sangli, State: Maharashtra, Pincode: 416416, Mobile: 9823177131, Email: [email protected] Name: Sainath Sudhakar Parsewar, Age:34, Designation: Partner Residential Address: Suman Nivas, Sidhivinayakpuram, Datta Nagar, Vishrambag, Sangli, Sangli Miraj Kupwad (M Corp.), Taluka:Miraj, District: Sangli, State: Maharashtra, Pincode: 416416, Mobile: , Email: Name: Sainath Sudhakar Parsewar, Age:31, Designation: Partner Office Address: 114 Vasant Market Yard Sangli, Sangli Miraj Kupwad (M Corp.), Taluka:Miraj, District: Sangli, State: Maharashtra, Pincode: 416416, Mobile: 9823177131, Email: [email protected] Name: Sainath Sudhakar Parsewar, Age:31, Designation: Partner Residential Address: Suman Nivas, Sidhivinayakpuram, Datta Nagar, Vishrambag, Sangli, Sangli Miraj Kupwad (M Corp.), Taluka:Miraj, District: Sangli, State: Maharashtra, Pincode: 416416, Mobile: , Email: Chief Quality Control Officer Commissionerate Of Agriculture Pune Encl. -

Provisional List of Not Shortlisted Candidates for the Post of Staff Nurse Under NHM, Assam (Ref: Advt No

Provisional List of Not Shortlisted Candidates for the post of Staff Nurse under NHM, Assam (Ref: Advt No. NHM/Esstt/Adv/115/08-09/Pt-II/ 4621 dated 24th Jun 2016 and vide No. NHM/Esstt/Adv/115/08-09/Pt- II/ 4582 dated 26th Aug 2016) Sl No. Regd. ID Candidate Name Father's Name Address Remarks for Not Shortlisting C/o-KAMINENI HOSPITALS, H.No.-4-1-1227, Vill/Town- Assam Nurses' Midwives' and A KING KOTI, HYDERABAD, P.O.-ABIDS, P.S.-KOTI Health Visitors' Council 1 NHM/SNRS/0658 A THULASI VENKATARAMANACHARI SULTHAN BAZAR, Dist.-RANGA REDDY, State- Registration Number Not TELANGANA, Pin-500001 Provided C/o-ABDUL AZIZ, H.No.-H NO 62 WARD NO 9, Assam Nurses' Midwives' and Vill/Town-GALI NO 1 PURAI ABADI, P.O.-SRI Health Visitors' Council 2 NHM/SNRS/0444 AABID AHMED ABDUL AZIZ GANGANAGAR, P.S.-SRI GANGANAGAR, Dist.-SRI Registration Number Not GANGANAGAR, State-RAJASTHAN, Pin-335001 Provided C/o-KHANDA FALSA MIYON KA CHOWK, H.No.-452, Assam Nurses' Midwives' and Vill/Town-JODHPUR, P.O.-SIWANCHI GATE, P.S.- Health Visitors' Council 3 NHM/SNRS/0144 ABDUL NADEEM ABDUL HABIB KHANDA FALSA, Dist.-Outside State, State-RAJASTHAN, Registration Number Not Pin-342001 Provided Assam Nurses' Midwives' and C/o-SIRMOHAR MEENA, H.No.-, Vill/Town-SOP, P.O.- Health Visitors' Council 4 NHM/SNRS/1703 ABHAYRAJ MEENA SIRMOHAR MEENA SOP, P.S.-NADOTI, Dist.-KAROULI, State-RAJASTHAN, Registration Number Not Pin-322204 Provided Assam Nurses' Midwives' and C/o-ABIDUNNISA, H.No.-90SF, Vill/Town- Health Visitors' Council 5 NHM/SNRS/0960 ABIDUNNISA ABDUL MUNAF KHAIRTABAD, -

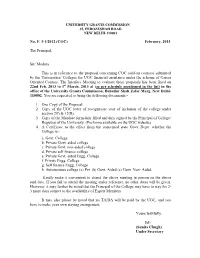

No. F. 1-1/2012 (COC) February, 2013 the Principal

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION 35, FEROZESHAH ROAD NEW DELHI-110001 No. F. 1-1/2012 (COC) February, 2013 The Principal, Sir/ Madam, This is in reference to the proposal concerning COC (add-on courses) submitted by the Universities/ Colleges for UGC financial assistance under the scheme of Career Oriented Courses. The Interface Meeting to evaluate these proposals has been fixed on 22nd Feb, 2013 to 1st March, 2013 at (as per schedule mentioned in the list) in the office of the University Grants Commission, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi- 110002. You are requested to bring the following documents:- 1. One Copy of the Proposal. 2. Copy of the UGC letter of recognition/ year of inclusion of the college under section 2(f) & 12(B). 3. Copy of the Mandate form duly filled and duly signed by the Principal of College/ Registrar of the University. (Proforma available on the UGC website) 4. A Certificate to the effect from the concerned state Govt. Deptt. whether the College is:- a. Govt. College b. Private Govt. aided college c. Private Govt. non-aided college d. Private self finance college e. Private Govt. aided Engg. College f. Private Engg. College g. Self finance Engg. College h. Autonomous college (a) Pvt. (b) Govt. Aided (c) Govt. Non- Aided. Kindly make it convenient to attend the above meeting in person on the above said date. If you fail to attend the meeting under reference, no other dates will be given. However, it may further be noted that the Principal of the College may have to stay for 2- 3 more days subject to the availability of Expert Members. -

The Sangli State

THE SANGLI STATE. BY RAO BAI."DUR D:'B. 'PARASNIS, HAPPY VALE, SATARA. BOMBAY: Lakshmi Art Printing Works, Sankli Street, Byculla. ( All J iglds Rese Printed by N. V. GhulDre II.t the L'>'K~1-nII ART PRINfJ:\G WORKS, 978. Sankli Street, Bycul1a, Bombay, alld Published bv Rao B!lhaduf D. R. P:.rast)is. Happy Vale. S:!Itara. To SHRIMANT C;; NTAMANRAO ALIAS APPASAHEB PATWARDHAN. CHIEF OF SANGLI, THIS BOOK IS WITH KIND PERMISSION DEDICATED. FOREWORD. This little book contains only a short sketch of the history of the Sangli State which represents the senior branch of the celebrated family of the Patwardhans. It is chiefly based on the authentic old records as well as the published correspondence of the Duke of Wellington, Sir l\1ountstuart Elphinstone, Sir Thomas Munro and others, who were so largely instrumental in establishing the British R;:lj in the Deccan, and who rendered valuable slIpport to this historical family of the Patwardhans, whosE' glorious deeds on the battle-field and deep attachment to the Briti:~!";' Throne are too well-known to need mention, If this brief narrative succeeci in awakening interest in the lovers of the :".Iaratha history, it will have achieved the ubject with which it is presented to the public. I am greatly indebted to Shrimant Sapusaheb Patwardhan, B.A., LL.B., Bar-at-law, for kindly giving me the benefit of his valuable suggestions, and also I have to thank Rao Bahadur M. K. Kumthekar, State Karbhari, Sangli, for his friendly advice. D. B. P. CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE I. -

DOMBAY Puesidencl

:o A Z E T '1' RE R DOMBAY PUESIDENCl. VOLUME XXIV-R. KOLHAPUR AND SOUTHERN MAHRATTA JMHIRS. U,VDER ·GOVERNMENT ORDERS. BOMBAY: Pl:JJSTED ~T TBB GOTitBIIllBNT CBNTB.U. PBUS. 1905. [lndiall ~Rs. 2-Io-o.) [EacUsb -Price-4 Shillings.] PREFACE. Volume XX~V of the Bombay Gazetteer was issued in 1886. _The present volume is intended to supplement the information contained therein by more recent statis· tics. It also contains notes for the reYision of the parent volume, which may prove of value when the time for revision of the original work arrives. R. .E. ENTHOVEN. Poona, Septembel' 1904. 153!-a KOLHAPUR PRINCIP .A.LITY. KOLHAPUR PRINCIPALITY. KOTES FOB THE REVISION OP VOLU~IE XXIY. Area.-'l'b; area has been iucrertsed from 2,493 square miles t() 3,165 square miles to accord with the measurements of the revi.,;ed Survey in prog-ress since 1895, The variations in the ca:e of each. State are given below :- Kolhii.pur (proper) +3 73 square miles, Vishii.lgad +113 de. Bavda + IOi do. Kagal (Senior) - 17 do. lchalkaranji + 96 do. Total +672 square miles. Land Revenue and Agriculture.-The Survey Settlement was first introduced into Kolha1mr territory about the year l 867. The rerisel settlement was commenced in 1895 and has now reached completion with the exception o£ a few Pet'h,aa in Kolhapur proper and some feudatory estates. By the new rates, introduced up to the year 1903, the total assessn1ent has been enhanced by Rs. 4,28,093 or 21·6 per cent. as under:- Assessment. -

DECLINE and FALL of BUDDHISM (A Tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface

1 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Dr. K. Jamanadas 2 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface “In every country there are two catogories of peoples one ‘EXPLOITER’ who is winner hence rule that country and other one are ‘EXPLOITED’ or defeated oppressed commoners.If you want to know true history of any country then listen to oppressed commoners. In most of cases they just know only what exploiter wants to listen from them, but there always remains some philosophers, historians and leaders among them who know true history.They do not tell edited version of history like Exploiters because they have nothing to gain from those Editions.”…. SAMAYBUDDHA DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) By Dr. K. Jamanadas e- Publish by SAMAYBUDDHA MISHAN, Delhi DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM A tragedy in Ancient India By Dr. K. Jamanadas Published by BLUEMOON BOOKS S 201, Essel Mansion, 2286 87, Arya Samaj Road, Karol Baug, New Delhi 110 005 Rs. 400/ 3 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface Table of Contents 00 Author's Preface 01 Introduction: Various aspects of decline of Buddhism and its ultimate fall, are discussed in details, specially the Effects rather than Causes, from the "massical" view rather than "classical" view. 02 Techniques: of brahminic control of masses to impose Brahminism over the Buddhist masses. 03 Foreign Invasions: How decline of Buddhism caused the various foreign Invasions is explained right from Alexander to Md. -

POLITICIAN in the MAKING I Curzon's Unprecedented Policy

53 Chapter III POLITICIAN IN THE MAKING i Curzon’s unprecedented policy towards the Princely States and the Princes themselves, had an immediate though inadvertent spinoff effect. For the first time a Viceroy of India was articulating the very problems that the millions of state subjects laboured under. This viceroy, whose aim, though it was not to ensure the loyalty of the states subject to their rulers, but the loyalty of the Native Princes to the Crown of England, had for the first time devised a strong arm method, as it were, to ensure good government in the States. For the first time a dispassionate Viceroy asked for annual administrative reports, made frequent visits to the States that were quite often followed up by severe indictment of the Rulers. While Curzon incited opposition and even the hostility of the Princes, the Foreign and Political Department as well as the political agents were on the reverse side. Curzon’s were the very ideas that formed the coherent basis upon which popular movements in the States were founded. 54 It was in Western Maharashtra that the first stirrings of national consciousness saw their birth. As we liave described earlier, the spread of English education had a profound effect on the nature of responses of the youth in the early years of the twentieth century. The, iT^j)st important factor that enabled Maharashtra a lead over even Bengal ^ a s the mass movement and resurgence during the ^th Century when Namdev, and Tukaram composed hymns, (abhanga), in praise of the Supreme One in Marathi and Dhyaneshwar translated the Gita into Marathi — the language of the masses - so that every man could derive spiritual guidance through it. -

DEAF Hosting FEB 2016.Pdf

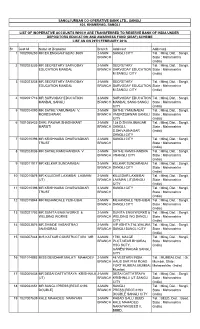

SANGLI URBAN CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD., SANGLI 404, KHANBHAG, SANGLI LIST OF INOPERATIVE ACCOUNTS WHICH ARE TRANSFERRED TO RESERVE BANK OF INDIA UNDER DEPOSITORS EDUCATION AND AWARNESS FUND (DEAF) SCHEME LIST AS ON 29TH FEBRUARY 2016 Sr Cust Id Name of Depositor Branch Address1 Address2 1 1002006250 MR EX.ENGG/63162/AC.8605 2-MAIN SANGLI CITY Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, BRANCH State : Maharashtra (India) 2 1002023235 MR SECRETARY SARVODAY 2-MAIN SECRETARY Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, EDUCATION MANDAL BRANCH SARVODAY EDUCATION State : Maharashtra M SANGLI CITY (India) 3 1002023235 MR SECRETARY SARVODAY 2-MAIN SECRETARY Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, EDUCATION MANDAL BRANCH SARVODAY EDUCATION State : Maharashtra M SANGLI CITY (India) 4 1002021716 MR SARVODAY EDUCATION 2-MAIN SARVODAY EDUCATION Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, MANDAL SANGLI BRANCH MANDAL SANG SANGLI State : Maharashtra CITY (India) 5 1002024090 MR SATHE YAMUNABAI V. 2-MAIN SATHE YAMUNABAI Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, MORESHWAR BRANCH VMORESHWAR SANGLI State : Maharashtra CITY (India) 6 1001055435 SHRI. PAWAR SHASHIKANT 2-MAIN 138 D SHIVAJINAGAR Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, MARUTI BRANCH SANGLI, State : Maharashtra S.SHIVAJINAGAR (India) SANGLI CITY 7 1002010396 MR KRISHNABAI DHARWADKAR 2-MAIN SANGLI CITY Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, TRUST BRANCH State : Maharashtra (India) 8 1002023036 MR SATHE RAMCHANDRA V. 2-MAIN SATHE RAMCHANDRA Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, BRANCH VSANGLI CITY State : Maharashtra (India) 9 1002011917 MR KELKAR SUNDARABAI 2-MAIN KELKAR SUNDARABAI Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, BRANCH SANGLI CITY State : Maharashtra (India) 10 1002010876 MR KILLEDAR LAXMIBAI LAXMAN 2-MAIN KILLEDAR LAXMIBAI Tal. : Miraj, Dist. : Sangli, (JT) BRANCH LAXMAN (JT)SANGLI State : Maharashtra CITY (India) 11 1002010396 MR KRISHNABAI DHARWADKAR 2-MAIN SANGLI CITY Tal. -

10-SEP-2012 Sum of Unpaid

DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED AMOUNT AS REFERRED IN SUB- SECTION (2) OF SECTION 205C OF THE COMPANIES ACT 1956 CIN NUMBER L22121DL2002PLC117874 NAME OF THE COMPANY HT MEDIA LIMITED DATE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING '10-SEP-2012 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend Rs. 58396/- Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend NIL Sum of matured deposit NIL Sum of interest on matured deposit NIL Sum of matured debentures NIL Sum of interest on matured debentures NIL Sum of application money due for refund NIL Sum of interest on application money due for refund NIL Proposed Date of Address of Investor Amount transfer to IEPF (DD- Sr.No Name of Investor (Complete address with Dist, State, Pin Code & Country) Folio Number of Securities Investment Type Due(in Rs.) MON-YYYY) 4 ASHIQ ALI BUILDING PANDARIBA CHARBAGH LUCKNOW LUCKNOW - 226001 District - LUCKNOW,State - UTTAR 1 JASBIR SINGH PRADESH,INDIA IN30133017863238 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 14.00 06-SEP-2013 B2/56 PHASE 2 ASHOK VIHAR NEW DELHI - 110001 District - 2 MEERA JAIN NEW DELHI,State - DELHI,INDIA IN30211310029850 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 2.00 06-SEP-2013 31-F CONNAUGHT PLACE NEW DELHI - 110001 District - NEW 3 SANJIV GUPTA DELHI,State - DELHI,INDIA IN30046810040359 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 37.00 06-SEP-2013 TATA AIG LIFE INS CO 3RD FLOOR ASHOKA ESTATE BARAKHAMBA ROAD NEW DELHI - 110001 District - NEW 4 ARVIND RANJAN SINHA DELHI,State - DELHI,INDIA IN30047643331884 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 25.00 06-SEP-2013 H.NO. 707/41, GALI NO . -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

GIPE-031362.Pdf

TilE INDIAN STATES' PEOPLE'S. CONFE~ENCE. i ~=:~oOadgi~::~t,- _________________ ...... ____ __ i 11\\111 u~u IIIli 11m mll\111\ llll 1l~ _ _ '\ GlPE-PUNE-0313 6 REPORT OF THE SECOND SESSIONs:·~""'"'·-~-~-,- Bombay: Saturday and Sunday, May 25 and 26,1929. PUBLISH.E:D BY Prof. G. R. ABHYANKAR, B. A., LL.B. BALVANTRAY MEHTA, MANISHANXER S. TRIVEDI. General Secretaries. The Indian States' People's Conference, Asboka Building, Princess Street, BO:\IBAY. 9th June 1981. Price Eight Anna.s. Printed by B. V. Parulekar, at the Bombay Vaibhav Preee, Servants of India Bociety'e Homo, Sandhnrat Road, Girgaon, Bvmbay. ' . Office-bearers of the Reception Committee ''OF THE SECOND SESSIONS. Chairman. · P~OF; G. R •. ·ABHYANKAR.; Vice-Chairmen. I GOVINDLAL .SHIVLAL, . , RAMDEOJr PooAR, \ KESHAVLAL MULCHAND1 • ' ~• I } 1 Secretaries. · AMRITLAL. D. SH!!TH... · . 'BALVANTRAY MEHTA,' , NIRANJ~ SHARMA AJIT •. MANISHANKER: TRIVE.DI, Treasure,.. I LAxH~CHANl) M. DosHI. THE INDIAN STATES' PEOPLE'8 CONFERENCE fVithin 1 hree years. 1. Within Three years :-Much water bas passel through the Ganges since we submitted our Report of the first sessions of the Conference to the public in September 1928. The seemingiy placid waters of the public life in India have passed through various turbulent channels within the short space of three years. The country has under gone a wonderful transformation, and the Indian States have shared in this upheaval. This Conference bas tried its utmost to do its· duty by the public in these momentous days. The readers will get an idea' about this by a cursory glance at the proceedings of the Conference and Committees published elsewhere. -

06 Chapter 3.Pdf

CHAPTER TWO ADMINISTRATION OF THE PATWARDHANS This chapter is devoted to survey the general administr ation of the Patwardhans from 1818 to 1910 in the background of the administrative system that the Patwardhans inherited from the Peshwas. The historical background combined with the geographical set-up would give a better understanding of the study of the Patwardhans* administration. Geographical Factor By the term "Sangli State" we mean the terri tory that was under the Sangli State during the 19th century."The Sangli State consisted of tracts extending from the British districts of Satara and Sholapur in the north to the river Tungbhadra in the south of the Bombay Presidency." "The State is divided into six widely scattered Talukas spread over four Collectorates of the Bombay Presidency."'1' The State consisted of six Talukas# namely# Mangalvedha# Kuchi# Miraj Prant# Terdal# Shahapur and Shirhatti. As to its geographical locations# we cannot give an isolated clear-cut picture# because# the state was divided scatteredly into many districts of the Bombay Presidency. The six talukas that formed the territory of the S were as follows: Mangalvedha was divided into five detached portions to the south of Bhima river. Actually it was to the south of Pandharpur in the Sholapur District within the angle formed by the rivers Man and Bhima. All the villages except four were in a ring fence. Mangalvedha was chief town of the taluka situated some 75 miles north-east of Sangli. The next taluka was Kuchi which was split up in six isolated portions and was to the east of Miraj Prant.