ELIMINATING MALARIA Case-Study 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Highlights of the Region II (Cagayan Valley) Population 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Date of Release: 20 August 2021 Reference No. 2021-317 • The population of Region II - Cagayan Valley as of 01 May 2020 is 3,685,744 based on the 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH). This accounts for about 3.38 percent of the Philippine population in 2020. • The 2020 population of the region is higher by 234,334 from the population of 3.45 million in 2015, and 456,581 more than the population of 3.23 million in 2010. Moreover, it is higher by 872,585 compared with the population of 2.81 million in 2000. (Table 1) Table 1. Total Population Based on Various Censuses: Region II - Cagayan Valley Census Year Census Reference Date Total Population 2000 May 1, 2000 2,813,159 2010 May 1, 2010 3,229,163 2015 August 1, 2015 3,451,410 2020 May 1, 2020 3,685,744 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority • The population of Region II increased by 1.39 percent annually from 2015 to 2020. By comparison, the rate at which the population of the region grew from 2010 to 2015 was lower at 1.27 percent. (Table 2) Table 2. Annual Population Growth Rate: Region II - Cagayan Valley (Based on Various Censuses) Intercensal Period Annual Population Growth Rate (%) 2000 to 2010 1.39 2010 to 2015 1.27 2015 to 2020 1.39 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority PSA Complex, East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 1101 Telephone: (632) 8938-5267 www.psa.gov.ph • Among the five provinces comprising Region II, Isabela had the biggest population in 2020 with 1,697,050 persons, followed by Cagayan with 1,268,603 persons, Nueva Vizcaya with 497,432 persons, and Quirino with 203,828 persons. -

Cancellation of Various Projects Posted in Websites Of

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS BATANES DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE REGIONAL OFFICE II Basco, Batanes BID BULLETIN NO. 2017-13 Subject: Cancellation of Invitations to Bid Posted in the websites of DPWH and PhilGEPS This Bid Bulletin No. 2017-13 is issued for the following purpose: To advise all concerned for the cancellation of Invitations to Bid posted in the websites of DPWH and PhilGEPS for the following Projects to enter into Negotiated Procurement: Due to Two and more Failed Biddings: 1. 17BA0048: Repair/Reconstruction of Retaining Wall/Seawall along Uyugan- Mahatao- Interior Road, Section K0032+300-K0032+320 2. 17BA0051: Rehabilitation/Improvement of MPB (Corazon Aquino Grandstand) 3. 17BA0058: Cluster 1 – 1. Const. (Completion) of Chanarian Elementary School Building 2. Renovation of Tukon School & CR 4. 17BA0059: Cluster 2 – 1. Rehabilitation of Mayan Elementary School Building 2. Rehabilitation of Raele Elementary School Building 5. 17BA0060: Cluster 3 - Rehabilitation/Expansion of Various Barangay Health Stations 1. Brgy. Itbud, Uyugan 2. Brgy. San Joaquin, Basco 3. Chanarian, Basco 4. San Vicente, Ivana Due to Emergency Cases: 1. 17BA0063: Repair of Ahtak & Valanga Port 2. 17BA0064: Repair of National Food Authority Building 3. 17BA0080: Construction of Guardrails along Airport-Mauyen Road 4. 17BA0081: Repair of Basco Central School Building 5. 17BA0082: Repair of Diptan Elementary School Building 6. 17BA0083: Repair of Philippine Coast Guard Building 7. 17BA0084: Repair/Reconstruction of Retaining Wall, Mayan-Chinapoliran Port Road 8. 17BA0085: Reconstruction of Collapsed Guard Wall/Retaining Wall and PCCP, Basco- Mahatao-Ivana-Uyugan-Imnajbu Road, K0008+375-K0008+860 9. -

Sitecode Year Region Penro Cenro Province

***Data is based on submitted maps per region as of January 8, 2018. AREA IN SITECODE YEAR REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT NAME OF ORGANIZATION SPECIES COMMODITY COMPONENT TENURE HECTARES 11-020900-0001-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco Chanarian Lone District 0.05 Tukon Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0002-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco Chanarian Lone District 0.08 Chanarian Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0003-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Itbayat Raele Lone District 0.08 Raele Barrio School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Fruit trees Protected Area 11-020900-0004-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Uyugan Itbud Lone District 0.16 Batanes General Comprehensive High School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Fruit trees Protected Area 11-020900-0005-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Savidug Lone District 0.19 Savidug Barrio School (lot 2) Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0006-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Nakanmuan Lone District 0.20 Nakanmuan Barrio School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0007-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco San Antonio Lone District 0.27 Diptan Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0008-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco San Antonio Lone District 0.27 DepEd -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

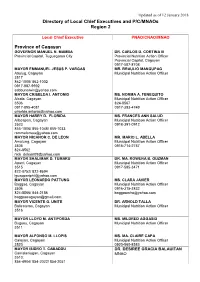

Directory of Local Chief Executives and P/C/Mnaos Region 2

Updated as of 12 January 2018 Directory of Local Chief Executives and P/C/MNAOs Region 2 Local Chief Executive PNAO/CNAO/MNAO Province of Cagayan GOVERNOR MANUEL N. MAMBA DR. CARLOS D. CORTINA III Provincial Capitol, Tuguegarao City Provincial Nutrition Action Officer Provincial Capitol, Cagayan 0917-587-8708 MAYOR EMMANUEL JESUS P. VARGAS MR. BRAULIO MANGUPAG Abulug, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3517 862-1008/ 862-1002 0917-887-9992 [email protected] MAYOR CRISELDA I. ANTONIO MS. NORMA A. FENEQUITO Alcala, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3506 824-8567 0917-895-4081 0917-393-4749 [email protected] MAYOR HARRY D. FLORIDA MS. FRANCES ANN SALUD Allacapan, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3523 0918-391-0912 855-1006/ 855-1048/ 855-1033 [email protected] MAYOR NICANOR C. DE LEON MR. MARIO L. ABELLA Amulung, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3505 0915-714-2757 824-8562 [email protected] MAYOR SHALIMAR D. TUMARU DR. MA. ROWENA B. GUZMAN Aparri, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3515 0917-585-3471 822-8752/ 822-8694 [email protected] MAYOR LEONARDO PATTUNG MS. CLARA JAVIER Baggao, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3506 0916-315-3832 824-8566/ 844-2186 [email protected] [email protected] MAYOR VICENTE G. UNITE DR. ARNOLD TALLA Ballesteros, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3516 MAYOR LLOYD M. ANTIPORDA MS. MILDRED AGGASID Buguey, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3511 MAYOR ALFONSO M. LLOPIS MS. MA. CLAIRE CAPA Calayan, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3520 0920-560-8583 MAYOR ISIDRO T. CABADDU DR. DESIREE GRACIA BALAUITAN Camalaniugan, Cagayan MNAO 3510; 854-4904/ 854-2022/ 854-2051 Updated as of 12 January 2018 MAYOR CELIA T. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES

2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES 16,604 BASCO (Capital) 7,907 Ihubok II (Kayvaluganan) 2,103 Ihubok I (Kaychanarianan) 1,665 San Antonio 1,772 San Joaquin 392 Chanarian 334 Kayhuvokan 1,641 ITBAYAT 2,988 Raele 442 San Rafael (Idiang) 789 Santa Lucia (Kauhauhasan) 478 Santa Maria (Marapuy) 438 Santa Rosa (Kaynatuan) 841 IVANA 1,249 Radiwan 368 Salagao 319 San Vicente (Igang) 230 Tuhel (Pob.) 332 MAHATAO 1,583 Hanib 372 Kaumbakan 483 Panatayan 416 Uvoy (Pob.) 312 SABTANG 1,637 Chavayan 169 Malakdang (Pob.) 245 Nakanmuan 134 Savidug 190 Sinakan (Pob.) 552 Sumnanga 347 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population UYUGAN 1,240 Kayvaluganan (Pob.) 324 Imnajbu 159 Itbud 463 Kayuganan (Pob.) 294 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Cagayan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population CAGAYAN 1,124,773 ABULUG 30,675 Alinunu 1,269 Bagu 1,774 Banguian 1,778 Calog Norte 934 Calog Sur 2,309 Canayun 1,328 Centro (Pob.) 2,400 Dana-Ili 1,201 Guiddam 3,084 Libertad 3,219 Lucban 2,646 Pinili 683 Santa Filomena 1,053 Santo Tomas 884 Siguiran 1,258 Simayung 1,321 Sirit 792 San Agustin 771 San Julian 627 Santa -

Final Report

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES THE FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT FOR THE LOWER CAGAYAN RIVER IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT VOLUME III-2 SUPPORTING REPORT ANNEX VII WATERSHED MANAGEMENT ANNEX VIII LAND USE ANNEX IX COST ESTIMATE ANNEX X PROJECT EVALUATION ANNEX XI INSTITUTION ANNEX XII TRANSFER OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 2002 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. NIKKEN Consultants, Inc. SSS JR 02- 07 List of Volumes Volume I : Executive Summary Volume II : Main Report Volume III-1 : Supporting Report Annex I : Socio-economy Annex II : Topography Annex III : Geology Annex IV : Meteo-hydrology Annex V : Environment Annex VI : Flood Control Volume III-2 : Supporting Report Annex VII : Watershed Management Annex VIII : Land Use Annex IX : Cost Estimate Annex X : Project Evaluation Annex XI : Institution Annex XII : Transfer of Technology Volume III-3 : Supporting Report Drawings Volume IV : Data Book The cost estimate is based on the price level and exchange rate of June 2001. The exchange rate is: US$1.00 = PHP50.0 = ¥120.0 Cagayan River N Basin PHILIPPINE SEA Babuyan Channel Apayao-Abulug ISIP Santa Ana Camalaniugan Dike LUZON SEA MabangucDike Aparri Agro-industry Development / Babuyan Channel by CEZA Catugan Dike Magapit PIS (CIADP) Lallo West PIP MINDANAO SEA Zinundungan IEP Lal-lo Dike Lal-lo KEY MAP Lasam Dike Evacuation System (FFWS, Magapit Gattaran Dike Alcala Amulung Nassiping PIP evacuation center), Resettlement, West PIP Dummon River Supporting Measures, CAGAYAN Reforestation, and Sabo Works Nassiping are also included in the Sto. Niño PIP Tupang Pared River Nassiping Dike Alcala Reviewed Master Plan. -

Health Beat Issue No. 75

contents 5 Health in Paradise 8 Household Helpers to Benefit from PhilHealth 9 9 Cementing DOH-LGU Partnership 12 QMMC Goes on a Meatless Monday 13 Bantay Presyon 16 News and Views on Stem Cell Therapy 16 Regulating Stem Cell Therapy 18 Permissibility in Islam 16 20 Hype or Hope? 22 Health Secretary's Cup 26 Hold It, Let's Debate 30 Health Bus Tours 33 GP Awards 36 Health Promoting Schools 37 Paputok Summit Calls for Culture Change 39 Neurocysticercosis 41 Kuliti (Sty in the Eye) 42 Manscaping - Dare to Go Bare, Guys! 45 Sustaining the Fight Against Leprosy 47 DOH-MSD-Zuellig 26 49 DOH Runners' Club jokes n'yo 33 42 beatBOX 21 stress RELIEF 25 KALAbeat 28 laughter HEALS 29 SAbeat 50 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH - National Center for Health Promotion 2F Bldg. 18, San Lazaro Compound, Sta. Cruz, Manila 1003, Philippines HEALTHbeat Tel. No. (63-2) 743-8438 Email: [email protected] Health Debates On March 14 (Manila Time), the 1.2 billion-member Catholic Church celebrated the announcement of a new Pope - Pope Francis. On March 15, Health Secretary Enrique T. Ona together with its partners signed the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of Republic Act 10354, otherwise known as the “Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health (RPRH) Act of 2012” in Baseco, Tondo, and calling it a momentous event in the history of health care. After the prescriptive period of 15 days, the IRR would have started full implemention on March 31 - Easter Sunday. But that would not be too easy for government agencies that are tasked to implement the said law. -

Batanes Electric Cooperative, Inc. National Road, Brgy

Batanes Electric Cooperative, Inc. National Road, Brgy. Kaychanarianan Basco, Batanes BASCO MAHATAO IVANA UYUGAN SABTANG ITBAYAT INVITATION TO RE-BID The BATANES ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC., through its Bids and Awards Committee (BAC), invites contractors to bid for the following contract: Contract Name: PROCUREMENT OF GOODS AND INFRASTRUCTURE FOR THE REPAIR OF UNDERGROUND DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM DAMAGED BY THE JULY 2019 TWIN EARTHQUAKE IN ITBAYAT Source of Fund: Government of the Philippines through the National Electrification Administration Calamity Subsidy LOT DESCRIPTION DURATION PROJECT SITE / FOB ABC Lot 1 Supply, Delivery, Installation, 90 CD Itbayat, Batanes 511,606.88 Testing and Commissioning of SCADA Lot 2 n/a Lot 3 Supply, Delivery of Cables and 60 CD Pier 18, 3,257,566.80 Electrical Materials vitas port via any ship to Basco (include port arrastre) / or as indicated in Bid docs Lot 4 Supply and Delivery of 30 CD BATANELCO Basco 718,874.88 Materials for Civil Works The BAC will conduct a regular public bidding for Lot 3 and simplified bidding for Lot 1 & 4 in accordance with R.A. 9184 also known as the Government Procurement Act and the Simplified Bidding Process for Electric Cooperatives. Further, to facilitate compliance with the new normal, virtual pre-bid conference and bid opening as well as electronic submissions among others shall be implemented. The times and deadlines set for the major procurement activities are shown below: 1. Availability / Issuance of Bid Documents From July 3, 2020 ( 8 AM – 5 PM ) @ Batanelco Office, Basco, Batanes 2. Virtual Pre-bid Conference July 10, 2020, 10 AM @ BATANELCO Station 2 Office, Barangay Kaychanarianan, Basco, Batanes 3. -

![Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9882/solid-waste-management-sector-project-financed-by-adbs-technical-assistance-special-fund-tasf-other-sources-3729882.webp)

Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 45146 December 2014 Republic of the Philippines: Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- other sources]) Prepared by SEURECA and PHILKOEI International, Inc., in association with Lahmeyer IDP Consult For the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHI Final Report December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHHI SR10a Del Carmen SR12: Poverty and Social SRs to RRP from 1 to 9 SPAR Dimensions & Resettlement and IP Frameworks SR1: SR10b Janiuay SPA External Assistance to PART I: Poverty, Social Philippines Development and Gender SR2: Summary of SR10c La Trinidad PART II: Involuntary Resettlement Description of Subprojects SPAR and IPs SR3: Project Implementation SR10d Malay/ Boracay SR13 Institutional Development Final and Management Structure SPAR and Private Sector Participation Report SR4: Implementation R11a Del Carmen IEE SR14 Workshops and Field Reports Schedule and REA SR5: Capacity Development SR11b Janiuay IEEE and Plan REA SR6: Financial Management SR11c La Trinidad IEE Assessment and REAE SR7: Procurement Capacity SR11d Malay/ Boracay PAM Assessment IEE and REA SR8: Consultation and Participation Plan RRP SR9: Poverty and Social Dimensions December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................5 A.