Penetration Enhancers in Ocular Drug Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brimonidine Tartrate; Brinzolamide

Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Draft Guidance on Brimonidine Tartrate ; Brinzolamide This draft guidance, when finalized, will represent the current thinking of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, or the Agency) on this topic. It does not establish any rights for any person and is not binding on FDA or the public. You can use an alternative approach if it satisfies the requirements of the applicable statutes and regulations. To discuss an alternative approach, contact the Office of Generic Drugs. Active Ingredient: Brimonidine tartrate; Brinzolamide Dosage Form; Route: Suspension/drops; ophthalmic Strength: 0.2%; 1% Recommended Studies: One study Type of study: Bioequivalence (BE) study with clinical endpoint Design: Randomized (1:1), double-masked, parallel, two-arm, in vivo Strength: 0.2%; 1% Subjects: Males and females with chronic open angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension in both eyes. Additional comments: Specific recommendations are provided below. ______________________________________________________________________________ Analytes to measure (in appropriate biological fluid): Not applicable Bioequivalence based on (95% CI): Clinical endpoint Additional comments regarding the BE study with clinical endpoint: 1. The Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) recommends conducting a BE study with a clinical endpoint in the treatment of open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension comparing the test product to the reference listed drug (RLD), each applied as one drop in both eyes three times daily at approximately 8:00 a.m., 4:00 p.m., and 10:00 p.m. for 42 days (6 weeks). 2. Inclusion criteria (the sponsor may add additional criteria): a. Male or nonpregnant females aged at least 18 years with chronic open angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension in both eyes b. -

Vocabulario De Morfoloxía, Anatomía E Citoloxía Veterinaria

Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) Servizo de Normalización Lingüística Universidade de Santiago de Compostela COLECCIÓN VOCABULARIOS TEMÁTICOS N.º 4 SERVIZO DE NORMALIZACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) 2008 UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA VOCABULARIO de morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria : (galego-español- inglés) / coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río, Servizo de Normalización Lingüística ; autores Matilde Lombardero Fernández ... [et al.]. – Santiago de Compostela : Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, 2008. – 369 p. ; 21 cm. – (Vocabularios temáticos ; 4). - D.L. C 2458-2008. – ISBN 978-84-9887-018-3 1.Medicina �������������������������������������������������������������������������veterinaria-Diccionarios�������������������������������������������������. 2.Galego (Lingua)-Glosarios, vocabularios, etc. políglotas. I.Lombardero Fernández, Matilde. II.Rodríguez Rio, Xusto A. coord. III. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística, coord. IV.Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, ed. V.Serie. 591.4(038)=699=60=20 Coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río (Área de Terminoloxía. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela) Autoras/res Matilde Lombardero Fernández (doutora en Veterinaria e profesora do Departamento de Anatomía e Produción Animal. -

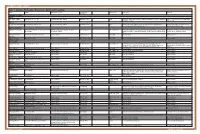

Table 1. Glaucoma Medications: Mechanisms, Dosing and Precautions Brand Generic Mechanism of Action Dosage/Avg

OPTOMETRIC STUDY CENTER Table 1. Glaucoma Medications: Mechanisms, Dosing and Precautions Brand Generic Mechanism of Action Dosage/Avg. % Product Sizes Side Effects Warnings Reduction CHOLINERGIC AGENTS Direct Pilocarpine (generic) Pilocarpine 1%, 2%, 4% Increases trabecular outflow BID-QID/15-25% 15ml Headache, blurred vision, myopia, retinal detachment, bronchiole constriction, Angle closure, shortness of breath, retinal narrowing of angle detachment Indirect Phospholine Iodide (Pfizer) Echothiophate iodide 0.125% Increases trabecular outflow QD-BID/15-25% 5ml Same as above plus cataractogenic iris cysts in children, pupillary block, Same as above, plus avoid prior to any increased paralysis with succinylcholine general anesthetic procedure ALPHA-2 AGONISTS Alphagan P (Allergan) Brimonidine tartrate 0.1%, 0.15% with Purite Decreases aqueous production, increases BID-TID/up to 26% 5ml, 10ml, 15ml Dry mouth, hypotension, bradycardia, follicular conjunctivitis, ocular irritation, Monitor for shortness of breath, dizziness, preservative uveoscleral outflow pruritus, dermatitis, conjunctival blanching, eyelid retraction, mydriasis, drug ocular redness and itching, fatigue allergy Brimonidine tartrate Brimonidine tartrate 0.15%, 0.2% Same as above Same as above 5ml, 10ml Same as above Same as above (generic) Iopidine (Novartis) Apraclonidine 0.5% Decreases aqueous production BID-TID/up to 25% 5ml, 10ml Same as above but higher drug allergy (40%) Same as above BETA-BLOCKERS Non-selective Betagan (Allergan) Levobunolol 0.25%, 0.5% Decreases -

Mechanism of Action of Nicotine in Isolated Urinary Bladder of Guinea-Pig

Br. J. Pharmacol. (1988), 95, 465-472 Mechanism of action of nicotine in isolated urinary bladder of guinea-pig Tetsuhiro Hisayama, Michiko Shinkai, lIssei Takayanagi & Toshie Toyoda Department of Chemical Pharmacology, Toho University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2-2-1, Miyama, Funabashi, Chiba 274, Japan 1 Nicotine produced a transient contraction of isolated strips of guinea-pig urinary bladder. The response to nicotine was antagonized by the nicotinic receptor antagonist, hexamethonium but was insensitive to tetrodotoxin. 2 The nicotine-induced contraction was potentiated by the cholinesterase inhibitor, physostig- mine, and was reduced to 50% and 70% by the muscarinic cholinoceptor antagonist, atropine and the sympathetic neurone blocking drug, guanethidine, respectively. Chemical denervation with 6- hydroxydopamine abolished the inhibitory effect of guanethidine. Simultaneous treatment with atropine and guanethidine did not abolish the response to nicotine, but the degree of inhibition was comparable to that obtained with atropine alone. 3 The nicotine-induced contraction was insensitive to bunazosin and yohimbine (al- and Cc2-adrenoceptor antagonists, respectively), and exogenously applied noradrenaline did not cause a contraction even in the presence of blockade of noradrenaline uptake mechanisms with desipramine and normetanephrine and of fi-adrenoceptors with propranolol, suggesting a non-adrenergic nature of the sympathomimetic effect of nicotine in this tissue. 4 The nicotine-induced contraction in the presence of atropine was abolished after desensitization of P2-purinoceptors with a, ,B-methylene adenosine 5'-triphosphate, a slowly degradable ATP ana- logue selective for P2-purinoceptors. By this desensitization, the response to ATP, but not to hista- mine, was also abolished. 5 A cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor flurbiprofen partially inhibited the nicotine-induced contraction. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME IOPIDINE® (Apraclonidine Hydrochloride) Eye Drops 0.5%

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME IOPIDINE® (apraclonidine hydrochloride) Eye Drops 0.5%. 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each mL of Iopidine Eye Drops 0.5% contains apraclonidine hydrochloride 5.75 mg, equivalent to apraclonidine base 5 mg. Excipient with known effect Benzalkonium chloride 0.1 mg per 1 mL as a preservative. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 2. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Eye drops, solution, sterile, isotonic. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1. Therapeutic indications Iopidine Eye Drops 0.5% are indicated for short-term adjunctive therapy in patients on maximally tolerated medical therapy who require additional IOP reduction. Patients on maximally tolerated medical therapy who are treated with Iopidine Eye Drops 0.5% to delay surgery should have frequent follow up examinations and treatment should be discontinued if the intraocular pressure rises significantly. The addition of Iopidine Eye Drops 0.5% to patients already using two aqueous suppressing drugs (i.e. beta-blocker plus carbonic anhydrase inhibitor) as part of their maximally tolerated medical therapy may not provide additional benefit. This is because apraclonidine is an aqueous-suppressing drug and the addition of a third aqueous suppressant may not significantly reduce IOP. The IOP-lowering efficacy of Iopidine Eye Drops 0.5% diminishes over time in some patients. This loss of effect, or tachyphylaxis, appears to be an individual occurrence with a variable time of onset and should be closely monitored. The benefit for most patients is less than one month. 4.2. Dose and method of administration Dose One drop of Iopidine Eye Drops 0.5% should be instilled into the affected eye(s) three times per day. -

Antihypertensive Agents Using ALZET Osmotic Pumps

ALZET® Bibliography References on the Administration of Antihypertensive Agents Using ALZET Osmotic Pumps 1. Atenolol Q7652: W. B. Zhao, et al. Stimulation of beta-adrenoceptors up-regulates cardiac expression of galectin-3 and BIM through the Hippo signalling pathway. British Journal of Pharmacology 2019;176(14):2465-2481 Agents: Isoproterenol; propranolol; carvedilol; atenolol; ICI-118551 Vehicle: saline; ascorbic acid, buffered; Route: SC; Species: Mice; Pump: 2001; Duration: 1 day; 2 days; 7 days; ALZET Comments: Dose ((ISO 0.6, 6, 20 mg/kg/d), (Prop 2 mg/kg/d), (Carv 2 mg/kg/d), (AT 2 mg/kg/d), (ICI 1 mg/kg/d)); saline with 0.4 mM ascorbic acid used; Controls were non-transgenic and received mp w/ vehicle; animal info (12-16 weeks, Male, (C57BL/6J, beta2-TG, Mst1-TG, or dnMst1-TG)); ICI-118551 is a beta2-antagonist with the structure (2R,3S)-1-[(7-methyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-4-yl)oxy]-3-(propan-2-ylamino)butan-2-ol; cardiovascular; Minipumps were removed to allow for washout of ISO overnight prior to imaging; Q7241: M. N. Nguyen, et al. Mechanisms responsible for increased circulating levels of galectin-3 in cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):8213 Agents: Isoproterenol, Atenolol, ICI-118551 Vehicle: Saline, ascorbic acid; Route: SC; Species: Mice; Pump: Not Stated; Duration: 48 Hours; ALZET Comments: Dose: ISO (2, 6 or 30 mg/kg/day; atenolol (2 mg/kg/day), ICI-118551 (1 mg/kg/day); 0.4 mM ascorbic used; animal info (12 14 week-old C57Bl/6 mice); cardiovascular; Q6161: C. -

Drug List (SORTED by TRADE with GENERIC EQUIVALENT)

NBEO Drug List (SORTED BY TRADE WITH GENERIC EQUIVALENT) Trade Generic Trade Generic Abilify aripiprazole Avandia rosiglitazone Accolate zafirlukast Avastin bevacizumab Accupril quinapril Azasan azathioprine Achromycin tetracycline AzaSite azithromycin Aciphex rabeprazole Avodart dutasteride Actos pioglitazone Azopt brinzolamide Acular ketorolac Bactrim trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole Acuvail ketorolac Bactrim DS trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole Advair fluticasone propionate Baquacil polyhexamethylene biguanide Advil ibuprofen Beconase AQ beclomethasone AeroBid flunisolide Benadryl diphenhydramine Afrin oxymetazoline Bepreve Bepotastine besilate Aggrenox aspirin and dipyridamole Besivance besifloxacin Alamast pemirolast Betadine povidone-iodine Alaway ketotifen Betagan levobunolol Aldactone spironolactone Betasept chlorhexidine topical Aleve naproxen sodium Betaseron interferon beta-1b Allegra fexofenadine Betimol timolol Allegra-D fexofenadine-pseudoephedrine Betoptic S betaxolol Alluvia lopinavir Biopatch chlorhexidine topical Alocril nedocromil Blephamide sulfacetamide-prednisolone Alomide lodoxamide Botox onabotulinum toxinA Alphagan P brimonidine Brolene propamidine isethionate Alrex loteprednol 0.2% Bromday bromfenac Ambien zolpidem Calamine zinc oxide and iron oxide Amicar aminocaproic acid Calan verapamil Amoxil amoxicillin Calgon Vesta chlorhexidine topical Amphocin amphotericin B Capoten captopril Anectine succinylcholine Carafate sucralfate Ansaid flurbiprofen Carbocaine mepivacaine HCl injection Antivert meclizine Cardizem diltiazem -

IOPIDINE® 0.5% (Apraclonidine Ophthalmic Solution) 0.5% As Base

IOPIDINE® 0.5% (apraclonidine ophthalmic solution) 0.5% As Base DESCRIPTION: IOPIDINE® 0.5% Ophthalmic Solution contains apraclonidine hydrochloride, an alpha adrenergic agonist, in a sterile isotonic solution for topical application to the eye. Apraclonidine hydrochloride is a white to off-white powder and is highly soluble in water. Its chemical name is 2-[(4-amino-2,6 dichlorophenyl) imino]imidazolidine monohydrochloride with an empirical formula of C9H11Cl3N4 and a molecular weight of 281.57. The chemical structure of apraclonidine hydrochloride is: Each mL of IOPIDINE 0.5% Ophthalmic Solution contains: Active: apraclonidine hydrochloride 5.75 mg equivalent to apraclonidine base 5 mg; . Inactives: sodium chloride, sodium acetate, sodium hydroxide and/or hydrochloric acid (pH 4.4-7.8), purified water and benzalkonium chloride 0.01% (preservative) CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Apraclonidine hydrochloride is a relatively selective alpha- 2-adrenergic agonist. When instilled in the eye, IOPIDINE 0.5% Ophthalmic Solution, has the action of reducing elevated, as well as normal, intraocular pressure (IOP), whether or not accompanied by glaucoma. Ophthalmic apraclonidine has minimal effect on cardiovascular parameters. Elevated IOP presents a major risk factor in glaucomatous field loss. The higher the level of IOP, the greater the likelihood of optic nerve damage and visual field loss. IOPIDINE 0.5% Ophthalmic Solution has the action of reducing IOP. The onset of action of apraclonidine can usually be noted within one hour, and maximum IOP reduction occurs about three hours after instillation. Aqueous fluorophotometry studies demonstrate that apraclonidine's predominant mechanism of action is reduction of aqueous flow via stimulation of the alpha-adrenergic system. -

Microscopic Anatomy of Ocular Globe in Diurnal Desert Rodent Psammomys Obesus (Cretzschmar, 1828) Ouanassa Saadi-Brenkia1,2* , Nadia Hanniche2 and Saida Lounis1,2

Saadi-Brenkia et al. The Journal of Basic and Applied Zoology (2018) 79:43 The Journal of Basic https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-018-0056-0 and Applied Zoology RESEARCH Open Access Microscopic anatomy of ocular globe in diurnal desert rodent Psammomys obesus (Cretzschmar, 1828) Ouanassa Saadi-Brenkia1,2* , Nadia Hanniche2 and Saida Lounis1,2 Abstract Background: The visual system of desert rodents demonstrates a rather high degree of development and specific features associated with adaptation to arid environment. The aim of this study is to carry out a descriptive investigation into the most relevant features of the sand rat eye. Results: Light microscopic observations revealed that the eye of Psammomys obesus diurnal species, appears similar to that of others rodent with characteristic mammalian organization. The eye was formed by the three distinct layers typical in vertebrates: fibrous tunic (sclera and cornea); vascular tunic (Iris, Ciliary body, Choroid); nervous tunic (retina). Three chambers of fluid fundamentals in maintaining the eyeball’s normal size and shape: Anterior chamber (between cornea and iris), Posterior chamber (between iris, zonule fibers and lens) and the Vitreous chamber (between the lens and the retina) The first two chambers are filled with aqueous humor whereas the vitreous chamber is filled with a more viscous fluid, the vitreous humor. These fluids are made up of 99.9% water. However, the main features, related to life style and arid environment, are the egg-shaped lens, the heavy pigmentation of the middle layer and an extensive folding of ciliary processes, thus developing a large surface area, for ultrafiltration and active fluid transport, this being the actual site of aqueous production. -

Accommodation

ACCOMMODATION (LECTURE SUPPLEMENT #1) Comparative methods of accommodation Because the eye has several optical elements there are a number of ways that the conjugate focus can be altered, and various creatures exploit most of these mechanisms Axial length: Changes in length of the eye have the effect of changing its optical power. Ex. Statically, The horse has a “ramp retina” which provides for a static difference in conjugate focus for different directions of gaze. On a longer time scale, Chickens show a change in axial length during development that depends on their refractive error. Monkeys have recently been shown (By Dr. Smith’s group) to have a similar mechanism. Dynamically, certain eels can shorten their axial length by constriction of a muscle. Corneal Shape: The cornea is the most powerful optical element in the eye, so small changes in its shape can produce significant changes in conjugate focus. Ex: Owls change the shape of their eye as a means of accommodating. Lens Position: The power of the eye’s optics is determined in part by the distance from lens to cornea, and many mammals, such as cats and raccoons, accommodate by simply moving the lens forward. Ex: The Lamprey lens is moved backwards by its cornealis muscle, resulting in active negative accommodation. The human lens moves forward somewhat during accommodation, contributing to the overall change in dioptric power. Lens Shape: Altering lens shape is the principal mechanism of primate accommodation. Among mammals this is rare, however. Dynamically, some birds and turtles constrict the lens using a combination of ciliary muscle and iris, causing the anterior surface to bulge forward.