Reclaiming the Female Body and Self-Deprecation in Stand-Up Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anna Crilly Writer/ Performer

Anna Crilly Writer/ Performer Anna is a hugely talented writer / performer. She has just filmed COBRA for Sky. She also recently played the role of Flavia in HORRIBLE HISTORIES: THE MOVIE. Before that, Anna filmed a pliot with Romesh Ranganathan. Other recent credits include THE HARRY HILL SITCOM, the BBC's STILL OPEN ALL HOURS and SUCCESSION for HBO. She featured in WITLESS for the BBC, and stars as Cath in THE REBEL, a comedy series for UKTV Gold, with Anita Dobson and Amit Shah. She also played the role of Jenny in an episode of Jimmy McGovern's MOVING ON Series 6, BLIND which aired on BBC1. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Kitty Laing Associate Agent [email protected] Isaac Storm +44 (0) 203 214 0915 [email protected] 020 3214 0997 Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE STORY OF KEN (short Laura Ingrid Oliver film) WYRDOES (short film) Lady Macbeth NAT LUURTSEMA Silk Screen Pictures Ltd TWO FAT LADIES (short Tracey Martin De Lange Jipsom film) United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE INTERVIEW (short film) The Interviewer Michael Jacob BBC 2 Television Production Character Director Company COBRA S2 Lin Various Sky One LADHOOD S2 Jonathan Schey BBc Studios HORRIBLE HISTORIES Flavia Dominic Brigstocke BBC THE HARRY HILL Chamain CPL SITCOM STILL OPEN ALL HOURS Mrs Snaith BBC (Series 5) SUCCESSION -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms TOMSETT, Eleanor Louise Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms Eleanor Louise Tomsett A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate declaration: I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acKnowledged. 4. The worK undertaKen towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Index 1 | Page

ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Index 1 | P a g e ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 31 May 2020 ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Monday, 1 June 2020 ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Tuesday, 2 June 2020 .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Wednesday, 3 June 2020 .................................................................................................................................... 21 Thursday, 4 June 2020 ........................................................................................................................................ 27 Friday, 5 June 2020 ............................................................................................................................................. 33 Saturday, 6 June 2020 ......................................................................................................................................... 39 2 | P a g e ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Sunday 31 May 2020 Program Guide Sunday, 31 May 2020 5:00am The Hive (Repeat,G) 5:10am Pocoyo -

5 April 2019 Page 1 of 15

Radio 4 Listings for 30 March – 5 April 2019 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 30 MARCH 2019 gradual journey towards all I now do, I am honoured to be a daughters to the coast to find out if if the problems and mum to a fabulous autistic son. In the UK, we have thousands concerns have changed. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m0003jxg) of autistic mothers, and indeed autistic parents & carers of all The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. kinds. Many bringing up their young families with love, As the women travel to their picnic by the sea in a minibus, we Followed by Weather. dedication and determination, watching their children grow and hear their stories. thrive. Do we enable and accept them? Balwinder was born and brought up in Glasgow and drives a SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (m0003jxj) Loving God, on this Mothering Sunday weekend, we ask that taxi. She was raised in a strict Sikh family and at the age of The Pianist of Yarmouk you guide and support all mothers, enabling them to gain eighteen her parents arranged her marriage. “With Mum and strength from you, cherishing all that their children will bring to Dad it was just, ‘You don’t need to study, you don’t need to Episode 5 the world, as young people deserving to be fully loved, and fully worry about work, because the only thing you’re going to be themselves. doing is getting married.’” Ammar Haj Ahmad reads Aeham Ahmad’s dramatic account of how he risked his life playing music under siege in Damascus. -

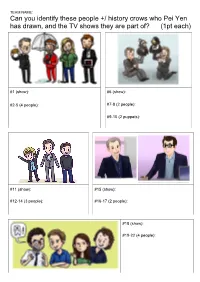

Acms Quiz – 2017

TEAM NAME: Can you identify these people +/ history crows who Pei Yen has drawn, and the TV shows they are part of? (1pt each) #1 (show): #6 (show): #2-5 (4 people): #7-8 (2 people): #9-10 (2 puppets): #11 (show): #15 (show): #12-14 (3 people): #16-17 (2 people): #18 (show): #19-22 (4 people): TEAM NAME: Can you identify these 2005 cartoon boys & their creator? (1pt each) 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 9) 7) 8) 10) TEAM NAME: Round #1 - Shows /15 pts Round #2 - Map /10 pts 1. 1. 2a. 2. 3. 2b. 4. 3a. 5. 6. 3b. 7. 3c. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 6. Round #3 - Fakes /10 pts 7a. 1. 7b. 2. 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10a. 6. 10b. 7. 8. 1 point for a complete right answer, 1/2 point 9. for getting it half right, 0 points for FAILURE* 10. * ignoble failure Round #4 - Award Winners /15 pts Round #5 - Venues /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7a. 7. 8. 7b. 9. 7c. 10. 7d. Round #6 - Names /10 pts 1. 8. 2. 9. 3. 10a. 4. 10b. 5. 10c. 6. 7. PLEASE DRAW US A CAT, IN THE 8. EVENT OF A TIE IT WILL 9. BE USED TO JUDGE 10. THE WINNER Round # /10 pts Round # /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. 10. 10. Round # /10 pts Round # /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. -

Photo by David Brennan Tyne Theatre and Opera House A6 Landscape AD.Qxp V 19/09/2017 14:49 Page 1

Photo by David Brennan tyne Theatre and Opera House a6 Landscape AD.qxp_v 19/09/2017 14:49 Page 1 Freshly Roasted Coffee Born and Speciality Teas Espresso Machinery brewed in Barista Training Byker brinkburnbrewery.co.uk Setting up a coffee shop? www.pumphreys* Buy online and -receivecoffee.co.uk free delivery on all orders over £50! * Give Pumphreys0191 a call 414 and 4510 benefit from the experience of established experts. @PumphreysCoffee pumphreyscoffee Pumphrey’s Coffee Freshly Roasted Coffee Speciality Teas Espresso Machinery Barista Training Setting up a coffee shop? www.pumphreys* Buy online and -receivecoffee.co.uk free delivery on all orders over £50! * Give Pumphreys0191 a call 414 and 4510 benefit from the experience of established experts. @PumphreysCoffee pumphreyscoffee Pumphrey’s Coffee tyne Theatre and Opera House a6 Landscape AD.qxp_v 19/09/2017 14:49 Page 1 Freshly Roasted Coffee Born and Speciality Teas Espresso Machinery brewed in Barista Training Byker brinkburnbrewery.co.uk Setting up a coffee shop? www.pumphreys* Buy online and -receivecoffee.co.uk free delivery on all orders over £50! * Give Pumphreys0191 a call 414 and 4510 benefit from the experience of established experts. @PumphreysCoffee pumphreyscoffee Pumphrey’s Coffee WELCOME TO OUR NEW WHAT’S ON GUIDE! What an amazing 2017 we’ve had so far, and there’s still plenty more in store! This year saw Tyne Theatre & Opera House celebrate its 150th Anniversary, and we’ve seen some brilliant events take place, including Tyne Theatre Productions’ spectacular West Side Story and our exciting collaboration with Whitley Bay Film Festival, The Cinema Years. -

To Headline This Is Tomorrow Festival 2019

WWW.NEVOLUME.CO.UK STEREOPHONICS TO HEADLINE THIS IS TOMORROW FESTIVAL 2019 WRITE FESTIVAL, SOUTH SHIELDS! WE’RE WOMEN ARE MINT AT COBALT STUDIOS! LISTENING! ISSUE #44 ARTIST SPOTLIGHT: SMOOTH & TURRELL! MAY 2019 WE SPEAK WITH THE BLINDERS! FOLLOW NE VOLUME WE REVIEW THE SHAKIN’ NIGHTMARES IN MIDDLESBROUGH! SUICIDE IN MUSIC ON SOCIAL MEDIA WE REVIEW MICHAEL GALLAGHER’S NEW EP! VINYL: LONG PLAY IN STOCKTON! PICK UP OUR FREE NORTH EAST MUSIC/CULTURE MAGAZINE! TO NE VOLUME MAGAZINE WELCOME ISSUE #44! Thank you so much for picking up NE Volume magazine - the magazine produced by local music CONTENTS and culture fans, for local music and culture fans. Those eagle-eyed NEWS readers among you may notice that there’s PG.5 Songs From Northern Britain! a piece of artwork in this edition announcing PG.10 Consett Festival 2019! the line-up for our 4th anniversary gig. Haven’t CULTURE spotted it yet? Take another look. We’re here to support local artists which is why we’ve put together an all North East line- PG.12 Write Festival, South Shields! up. Anyhow, so here’s what to look out for this month. In this edition, I speak with Stereophonics as they prepare to play This PG.15 Sunderland Shorts Film Festival! is Tomorrow in Newcastle; Tobias Halford provides you with his honest opinion of The Shakin’ Nightmares at Hey Base Camp in SPOTLIGHTS Middlesbrough; we keep you up-to-date with what’s happening in the region this month including Women are Mint at Cobalt PG.22 Artist Spotlight: Smoove & Turrell! Studios in Newcastle, The Membranes at Westgarth Social Club in Middlesbrough and Consett Festival; in our culture section PG.23 Business Spotlight: Parmo Photography! we preview Write Festival in South Shields, and so much more. -

May All Our Voices Be Heard

JUST THE TONIC EDFRINGE VENUES 2019 FULL LISTINGS AND MORE 1st - 25th August 2019 EDINBURGH FRINGE PROUDLY SPONSORED BY NO ONE - TOTALLY INDEPENDENT 7 venues 8 Bars 4000 performances 98.9%* 19 performance spaces 182 shows comedy *THE OTHER 1.1% ARE FUN AS WELL… CHALLENGE: GO FIND THE OTHER 2 SHOWS INSIDE! MAY ALL OUR VOICES BE HEARD www.justthetonic.com Big Value is the best Big Value compilation show at The Fringe. It’s an Comedy Shows excellent barometer of The longest running stand up compilation show on the fringe. We ask promoter people who are going Darrell Martin to take a look at at it’s fine heritage. to go on to big things. Starting in 1996, with a line up that included The show is currently produced by Darrell And I’m not just saying Milton Jones and Adam Bloom, the Big Value Martin, who runs Just the Tonic. It wasn’t Comedy Shows have been selecting the always that way. Many years ago Darrell was that because I did it. stars of the future for almost 25 years. a keen performer that was desperate to be part of the show. Comedians such as Jim Jeffries, Pete Harris was the person who set it all up. Sarah Millican, Jon Richardson and He ran a chain of clubs called Screaming ROMESH Romesh Ranganathan are some of Blue Murder. According to Adam Bloom, it all RANGANATHAN came out of a conversation where Adam said Big Value Comedy Show 2011 + 2012 those who were first exposed to the to Pete that he wanted to go to Edinburgh but couldn’t afford it. -

"Don't Be Such a Girl, I'm Only Joking!" Post-Alternative Comedy, British Panel Shows, and Masculine Spaces" (2017)

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 "Don't Be Such a Girl, I'm Only Joking!" Post- alternative Comedy, British Panel Shows, and Masculine Spaces Lindsay Anne Weber University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Weber, Lindsay Anne, ""Don't Be Such a Girl, I'm Only Joking!" Post-alternative Comedy, British Panel Shows, and Masculine Spaces" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1721. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1721 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “DON’T BE SUCH A GIRL, I’M ONLY JOKING!” POST-ALTERNATIVE COMEDY, BRITISH PANEL SHOWS, AND MASCULINE SPACES by Lindsay Weber A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT “DON’T BE SUCH A GIRL, I’M ONLY JOKING!” POST-ALTERNATIVE COMEDY, BRITISH PANEL SHOWS, AND MASCULINE SPACES by Lindsay Weber The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Elana Levine This thesis discusses the gender disparity in British panel shows. In February 2014 the BBC’s Director of Television enforced a quota stating panel shows needed to include one woman per episode. This quota did not fully address the ways in which the gender imbalance was created. -

MANS NOT OLD Jon Richardson Brings His 'Old Man' Tour to This Years Bath Comedy Festival

Mar/Apr free inwww.inbath.netbath MANS NOT OLD Jon Richardson brings his 'Old Man' tour to this years Bath Comedy Festival +What's On | Bath Comedy Festival Preview Bath Half Runners' Stories | Lewis Moody Bath Racecourse Preview Afternoon Tea Focus | ItaliAN Cuisine | Mother's Day Music | Kim Wilde | Easter Days OUt Property | Focus on Lettings | NEw HOmes | and More InBath favourite Viv Groskop and acclaimed Australian comedian Sarah Bennetto, not to mention the Finals of the New Act Competition. The Ring O Bells hosts a concentrated programme of seriously top quality acts performing in the wonderful intimate space which has been a firm favourite for Bath Comedy shows for many years. This year's line-up includes some fantastic talent including Rachel Parris, Ashley Storrie, Janey Godley, Archie Maddocks, Markus Birdman, Diane Spencer, Matt Green and Sally-Anne Hayward. Ab Fab star to host Wine Trail Perennial flagship hit immersive show The Wine Arts Trail makes its bonkers boozy way around Bath's secret corners in the big red Routemaster bus on Sunday 8th April and rumours abound as to the wondrous delights in store this year – organisers promise a very special experience hosted by guest clippie Helen Lederer (subject to availability). Festival on tour! Residents of Bradford on Avon and those up for a ten minute train ride won't miss out as Radio 4 favourite Mark Steel is appearing at St Margaret's Hall on Friday 13th April, and Frome people can look forward to a walking tour with a difference – Rare Species will be presenting Jon Richardson "Frome – The Fecund Coming". -

Sarah Millican

Sarah Millican An iron fist in a marigold glove Guardian • Nominee: Best Entertainment Performance, British Academy Television Awards (BAFTA) 2014 • Nominee: Best Female TV Comic, The British Comedy Awards 2013 • Nominee: People’s Choice Award: King or Queen of Comedy, The British Comedy Awards 2013 • Nominee: Best Entertainment Performance, British Academy Television Awards (BAFTA) 2013 • Nominee: People’s Choice Award: King or Queen of Comedy, The British Comedy Awards 2012 • Nominee: Best Female TV Comic, The British Comedy Awards 2012 • Winner: People’s Choice Award: King or Queen of Comedy, The British Comedy Awards 2011 • Nominee: Best Female TV Comic, The British Comedy Awards 2011 • Nominee: Best Female TV Comic, The British Comedy Awards 2010 • Nominee: Best Female Comedy Breakthrough Artist, The British Comedy Awards 2010 • Nominee: Foster’s Edinburgh Comedy Award 2010 • Winner: Chortle Awards Best Headliner 2010 • Nominee: Barry Award, Melbourne Comedy Festival 2009 • Winner: Chortle Awards Breakthrough Act 2009 • Winner: if. Comedy Best Newcomer 2008 • Winner: Best Breakthrough act, North-West Comedy Awards 2006 • Nominee: Chortle Awards Best Newcomer 2006 • Winner: Amused Moose Comedy Awards 2005 • Runner Up: BBC New Comedy Awards 2005 • Runner Up: So You Think You’re Funny 2005 • Runner Up: Funny Women 2005 Sarah Millican is an award-winning stand-up comedian and writer. Since winning the 2008 if.comedy Best Newcomer Award at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival for her debut solo show, Sarah Millican’s Not Nice, Sarah has fast-established herself as a household name, being nominated three times for The British Comedy Awards People’s Choice: Queen of Comedy and winning the award in 2011. -

The Red Nose Designs Comic Relief Doesn't Want You To

Thursday 16th February 2017 THE RED NOSE DESIGNS COMIC RELIEF DOESN’T WANT YOU TO SEE A new film LEAKED from a source at Comic Relief REVEALS footage of its creative design team having their bi-annual BRAINSTORM (sorry, we probably shouldn’t have capitalised that bit.) The footage reveals an unsavoury smorgasbord of shocking design ideas which provide a revealing insight into the design team behind the nation’s favourite nose-based charity. If this footage is anything to go by, this team proves that there in fact IS such thing as a bad idea. Watch it here now In actual fact, the film is the first sketch from a new original online comedy series from Comic Relief. Kicking off the series are five of the UK’s most exciting new comedians, Jamie Demetriou (Fleabag, Rovers), Natasia Demetriou (8 out of 10 Cats Does Countdown), Rhys James (Mock the Week), Lolly Adefope (Plebs, Josh) and Nick Mohammed (Bridget Jones’s Baby, Absolutely Fabulous, Miranda). ‘The Designers’ is an original Red Nose Day sketch, from new writers Daniel Audritt and Kat Butterfield, that sees hapless Rhys James on his first day at Comic Relief, stumbling into an enthusiastic but idiotic group of designers, led by Jamie Demetriou, as they struggle to come up with the next big Nose design. The hotly-tipped comedy stars jumped at the chance to get involved in this years Red Nose Day campaign, taking time out of their hectic schedules; Jamie’s TV pilot Stath has been commissioned by E4 whilst Nick Mohammed is performing his sell-out Edinburgh show at the Soho Theatre, as well as co-writing a new Channel 4 series.