Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lee's Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett's Charge

Defense Number 54 A publication of the Center for Technology and National Security Policy A U G U S T 2 0 0 6 National Defense University Horizons Lee’s Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett’s Charge by David C. Gompert and Richard L. Kugler I think that this is the strongest position on which Robert E. Lee is widely and rightly regarded as one of the fin- to fight a battle that I ever saw. est generals in history. Yet on July 3, 1863, the third day of the Battle — Winfield Scott Hancock, surveying his position of Gettysburg, he ordered a frontal assault across a mile of open field on Cemetery Ridge against the strong center of the Union line. The stunning Confederate It is my opinion that no 15,000 men ever arrayed defeat that ensued produced heavier casualties than Lee’s army could for battle can take that position. afford and abruptly ended its invasion of the North. That the Army of Northern Virginia could fight on for 2 more years after Gettysburg was — James Longstreet to Robert E. Lee, surveying a tribute to Lee’s abilities.1 While Lee’s disciples defended his decision Hancock’s position vigorously—they blamed James Longstreet, the corps commander in This is a desperate thing to attempt. charge of the attack, for desultory execution—historians and military — Richard Garnett to Lewis Armistead, analysts agree that it was a mistake. For whatever reason, Lee was reti- prior to Pickett’s Charge cent about his reasoning at the time and later.2 The fault is entirely my own. -

James Longstreet and the Retreat from Gettysburg

“Such a night is seldom experienced…” James Longstreet and the Retreat from Gettysburg Karlton Smith, Gettysburg NMP After the repulse of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Assault on July 3, 1863, Gen. Robert E. Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, knew that the only option left for him at Gettysburg was to try to disengage from his lines and return with his army to Virginia. Longstreet, commander of the army’s First Corps and Lee’s chief lieutenant, would play a significant role in this retrograde movement. As a preliminary to the general withdrawal, Longstreet decided to pull his troops back from the forward positions gained during the fighting on July 2. Lt. Col. G. Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet’s adjutant general, delivered the necessary orders to Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, commanding one of Longstreet’s divisions. Sorrel offered to carry the order to Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law, commanding John B. Hood’s division, on McLaws’s right. McLaws raised objections to this order. He felt that his advanced position was important and “had been won after a deadly struggle; that the order was given no doubt because of [George] Pickett’s repulse, but as there was no pursuit there was no necessity of it.” Sorrel interrupted saying: “General, there is no discretion allowed, the order is for you to retire at once.” Gen. James Longstreet, C.S.A. (LOC) As McLaws’s forward line was withdrawing to Warfield and Seminary ridges, the Federal batteries on Little Round Top opened fire, “but by quickening the pace the aim was so disturbed that no damage was done.” McLaws’s line was followed by “clouds of skirmishers” from the Federal Army of the Potomac; however, after reinforcing his own skirmish line they were driven back from the Peach Orchard area. -

Gettysburg National Military Park & Eisenhower National Historic Site

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Gettysburg National Military Park & Eisenhower National Historic Site Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/083 THIS PAGE: North Carolina State Monument (NPS Photo) ON THE COVER: Gettysburg NMP, looking toward Cemetery Ridge Cover photo by Bill Dowling, courtesy of the Gettysburg Foundation Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Site Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/083 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

PICKETT's CHARGE Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT

PICKETT’S CHARGE I Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Pickett's Charge A Student Education Program at Gettysburg National Military Park TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 How To Use This Booklet ••••..••.••...• 3 Section 2 Program Overview . • . • . • . • . 4 Section 3 Field Trip Day Procedures • • • . • • • . 5 Section 4 Essential Background and Activities . 6 A Causes ofthe American Civil War ••..•...... 7 ft The Battle ofGettysburg . • • • . • . 10 A Pi.ckett's Charge Vocabulary •............... 14 A Name Tags ••.. ... ...........• . •......... 15 A Election ofOfficers and Insignia ......•..•.. 15 A Assignm~t ofSoldier Identity •..••......... 17 A Flag-Making ............................. 22 ft Drill of the Company (Your Class) ........... 23 Section 5 Additional Background and Activities .••.. 24 Structure ofthe Confederate Army .......... 25 Confederate Leaders at Gettysburg ••.•••.••• 27 History of the 28th Virginia Regiment ....... 30 History of the 57th Virginia Regiment . .. .... 32 Infantry Soldier Equipment ................ 34 Civil War Weaponry . · · · · · · 35 Pre-Vtsit Discussion Questions . • . 37 11:me Line . 38 ... Section 6 B us A ct1vities ........................• 39 Soldier Pastimes . 39 Pickett's Charge Matching . ••.......•....... 43 Pickett's Charge Matching - Answer Key . 44 •• A .•. Section 7 P ost-V 1s1t ctivities .................... 45 Post-Visit Activity Ideas . • . • . • . • . 45 After Pickett's Charge . • • • • . • . 46 Key: ft = Essential Preparation for Trip 2 Section 1 How to Use This Booklet Your students will gain the most benefit from this program if they are prepared for their visit. The preparatory information and activities in this booklet are necessary because .. • students retain the most information when they are pre pared for the field trip, knowing what to expect, what is expected of them, and with some base of knowledge upon which the program ranger can build. -

Did Meade Begin a Counteroffensive After Pickett's Charge?

Did Meade Begin a Counteroffensive after Pickett’s Charge? Troy D. Harman When examining the strategy of Union Major General George Gordon Meade at the battle of Gettysburg, one discovers lingering doubts about his leadership and will to fight. His rivals viewed him as a timid commander who would not have engaged at Gettysburg had not his peers corralled him into it. On the first day of the battle, for instance, it was Major General John Fulton Reynolds who entangled the left wing of the federal army thirty miles north of its original defensive position at Westminster, Maryland. Under the circumstances, Meade scrambled to rush the rest of his army to the developing battlefield. And on the second day, Major General Daniel Sickles advanced part of his Union 3rd Corps several hundred yards ahead of the designated position on the army’s left, and forced Meade to over-commit forces there to save the situation. In both instances the Union army prevailed, while the Confederate high command struggled to adjust to uncharacteristically aggressive Union moves. However, it would appear that both outcomes were the result of actions initiated by someone other than Meade, who seemed to react well enough. Frustrating to Meade must have been that these same two outcomes could have been viewed in a way more favorable to the commanding general. For example, both Reynolds and Sickles were dependent on Meade to follow through with their bold moves. Though Reynolds committed 25,000 Union infantry to fight at Gettysburg, it was Meade who authorized his advance into south-central Pennsylvania. -

“Never Have I Seen Such a Charge”

The Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign “Never Have I Seen Such a Charge” Pender’s Light Division at Gettysburg, July 1 D. Scott Hartwig It was July 1 at Gettysburg and the battle west of town had been raging furiously since 1:30 p.m. By dint of only the hardest fighting troops of Major General Henry Heth’s and Major General Robert E. Rodes’s divisions had driven elements of the Union 1st Corps from their positions along McPherson’s Ridge, back to Seminary Ridge. Here, the bloodied Union regiments and batteries hastily organized a defense to meet the storm they all knew would soon break upon them. This was the last possible line of defense beyond the town and the high ground south of it. It had to be held as long as possible. To break this last line of Union resistance, Confederate Third Corps commander, Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill, committed his last reserve, the division of Major General Dorsey Pender. They were the famed Light Division of the Army of Northern Virginia, boasting a battle record from the Seven Days battles to Chancellorsville unsurpassed by any other division in the army. Arguably, it may have been the best division in Lee’s army. Certainly no organization of the army could claim more combat experience. Now, Hill would call upon his old division once more to make a desperate assault to secure victory. In many ways their charge upon Seminary Ridge would be symbolic of why the Army of Northern Virginia had enjoyed an unbroken string of victories through 1862 and 1863, and why they would meet defeat at Gettysburg. -

Thomas Mays on Law's Alabama Brigade in the War Between the Union and the Confederacy

Morris Penny, J. Gary Laine. Law's Alabama Brigade in the War Between the Union and the Confederacy. Shippensburg, Penn: White Mane Publishing, 1997. xxi + 458 pp. $37.50, paper, ISBN 978-1-57249-024-6. Reviewed by Thomas D. Mays Published on H-CivWar (August, 1997) Anyone with an interest in the battle of Get‐ number of good maps that trace the path of each tysburg is familiar with the famous stand taken regiment in the fghting. The authors also spice on Little Round Top on the second day by Joshua the narrative with letters from home and interest‐ Chamberlain's 20th Maine. Chamberlain's men ing stories of individual actions in the feld and and Colonel Strong Vincent's Union brigade saved camp, including the story of a duel fought behind the left fank of the Union army and may have in‐ the lines during the siege of Suffolk. fluenced the outcome of the battle. While the leg‐ Laine and Penny begin with a very brief in‐ end of the defenders of Little Round Top contin‐ troduction to the service of Evander McIver Law ues to grow in movies and books, little has been and the regiments that would later make up the written about their opponents on that day, includ‐ brigade. Law, a graduate of the South Carolina ing Evander Law's Alabama Brigade. In the short Military Academy (now known as the Citadel), time the brigade existed (1863-1865), Law's Al‐ had been working as an instructor at a military abamians participated in some of the most des‐ prep school in Alabama when the war began. -

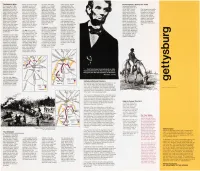

The Battle in Brief Gettysburg National Cemetery for Your Safety

The Battle In Brief bered, the Union forces the Union left broke under George Pickett Park Programs—History For Today In the spring of 1863, managed to hold until through D. E. Sickles' charged across the Gettysburg battlefield Gen. Robert E. Lee re afternoon when they advance lines at the open field toward the looks today much as it organized the Army of were overpowered and Peach Orchard, left the Union center. Raked by did in 1863. Fences, Park rangers lead walks, Northern Virginia into driven back through Wheatfield strewn with artillery and rifle fire, rocks, hills, cannon, give talks, and present three infantry corps and town. In the confusion, dead and wounded, Pickett's men reached and even the monu programs at various lo began marching west thousands of Union sol and turned the base of but failed to break the ments, which weren't cations on the battle ward from Fredericks diers were captured be Little Round Top into a Union line; only one in here then, wait like an field to help visitors burg, Va., through the fore they could rally on shambles. R. S. Ewell's three retreated to safety. empty stage for an au visualize the personal gaps of the Blue Ridge, Cemetery Hill south of attack proved futile dience with the imagi impact of past events. then northward into town. Long into the against the entrenched The Confederate army nation to remember the Check at the visitor Maryland and Pennsyl night Union troops la Union right on East that staggered back battle, to ponder and center for programs vania. -

Touring the Battlefield

Touring the Battlefield Barlow Knoll When Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Confederates smashed Union defend- ers here at 3 p.m., the Federal line north of Gettysburg collapsed. East Cavalry Battlefield Site Here on July 3, during the cannonade that pre- ceded Pickett’s Charge, Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg intercepted and then checked Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cav- alry. For more informa- tion, ask for the free self- guiding tour brochure at the park visitor center in- formation desk. Self-Guiding Auto Tour The complete 24-mile auto July 2, 1863 Federal cannon bombard- 12,000-man “Pickett’s tour starts at the visitor ed South ern forces cross- Charge” against the Fed- cen ter and includes the 4 North Carolina Memorial ing the Rose Farm toward eral center. This was the following 16 tour stops, Early in the day, the Con- the Wheatfield until about climactic moment of the the Barlow Knoll Loop, federate army positioned 6:30 p.m., when Confeder- battle. On July 4, Lee’s and the Historic Down- itself on high ground here ate attacks overran this army began retreating. town Gettysburg Tour. The along Seminary Ridge, position. route traces the three- through town, and north Total casualties (killed, day battle in chron o logi- of Cemetery and Culp’s 11 Plum Run wounded, captured, and cal order. It is flexible hills. Union forces occu- While fighting raged to missing) for the three days enough to allow you to pied Culp’s and Cemetery the south at the Wheat- of fighting were 23,000 include, or skip, cer tain hills, and along Cemetery field and Little Round Top, for the Union army and as points and/or stops, based Ridge south to the Round retreating Union soldiers many as 28,000 for the on your interest. -

Battlefield Footsteps Programs Teacher and Student Guide

BATTL FI LD FOOTST PS Gettysburg National Military Park Preparation Materials for the Courage, Determination, and eadership student programs. U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Battlefield Footsteps Programs Teacher and Student Guide The following lessons have been prepared for you to present over the course of one or two class periods and/or to send home as study guides for your students. They will prepare them for the trip as well as build their anticipation for the program. Please be sure to have the students wear a nametag with their FIRST NAMES ONLY in large letters so that we can get to know them quickly on Field Trip Day. Causes of the American Civil War a lesson for all programs page 3 What was the Civil War really fought over? Let the people who lived through this emotional and complex time period tell you what it was like, and why they became involved in a war that would ultimately claim 620,000 lives. th “Courage and the 9 Massachusetts Battery” July 2, 1863 page 6 “Retreat by prolonge, firing!” is the order as your unit is sacrificed to buy time for the infantry to plug the gaps along Cemetery Ridge. Follow in the path and harried activity of this courageous artillery unit. “Determination and the 15th Alabama Infantry” July 2, 1863 page 10 Climb Big Round Top and attack Little Round Top after a forced march, and without any water! This program illustrates the strength, stamina and determination of these Confederate infantrymen. “Leadership and the 6th Wisconsin Infantry” July 1, 1863 page 14 “Align on the Colors” with Lt. -

Battle of Gettysburg Day 2 Reading Comprehension Name: ______

Battle of Gettysburg Day 2 Reading Comprehension Name: _________________________ Read the passage and answer the questions. The Fishhook During the night of July 1st, most of the remaining Union and Confederate forces arrived in Gettysburg. The Union army was able to establish a strong line in the shape of a fishhook running over two miles from Cemetery Hill, along Cemetery Ridge and terminating at Culp's Hill. Confederate lines ran the length of Seminary Ridge, through the town of Gettysburg and terminated at a location opposite of Culp's Hill. In all, Confederate lines stretched for more than five miles. The stage was set for a massive battle. Missing Intelligence Without intelligence from J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry, however, Lee could not be certain of the exact positioning of Union forces, thus, his battle strategy for the second day of Gettysburg was somewhat flawed. Lee planned to launch a series of successive attacks with Longstreet's Corps on the Union left flank. The series of attacks and the diagonal formation of the attackers, would, theoretically, prevent the shifting of Union troops to reinforce the left flank. Meanwhile, other divisions would attack Union positions at Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. Lee did not know, however, that Union Major General Daniel Sickels and his troops were positioned in between Confederate forces and the Union left flank. Attacks on Devil's Den and Little Round Top On the sweltering afternoon of July 2nd, General Longstreet's soldiers engaged Sickels' III Union Corps, driving them back and forcing Union Commander Meade to send 20,000 reinforcements. -

United States Department of the Interior

G e r f t h o • U i . s . 10-23 (M ay 1929) UNITED STATES 30S//33 93? DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE -Gatiyshurg. n a t i o n a l ''p a r k F I L E N O . VISTA CUTTING PROJECT Area of Little Round Top, Devil's Den, the TTheatfield, and Peach Orchard. IMPORTANT Frederick Tilberg This file constitutes a part of the official records of the Assistant Research Technician National Park Service and should not be separated or papers December 28, 1939 withdrawn without express authority of the official in charge. All Files should be returned promptly to the File Room. Officials and employees will be held responsible for failure to observe these rules, which are necessary to protect the integrity of the official records. ARNO B. CAMMERER, O 8. OATBRNMEfT ntMTIWA O R IG I 6 7410 Director. 4$- VISTA CUTTING PROJECT - Gettysburg National Military Park Gettysburg, Pennsylvania Summary Account of the Battle in the Area of Little Round Top, Devil's Den, the hheatfield, and Ee'aoh Orchard. The Union line, upon its establishment by noon "of July 2, was entirely south of the town of Gettysburg, the right flank resting near Spangler's Spring, the left at Little Round Top. It was the center and left of the Union Line, extending from Ziegler's Grove southward, which was to bear the impact of battle on the afternoon of July 2. Beginning at this grove of trees and extending southward along the ridge were the Divisions of Hays, Gibbon and Caldwell of Hancock's Second Corps.