FI-STAR Deliverable D1.1 Has Already Discussed Legal Requirements Related to Data Security Breach Notifications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Data Engineer Cala Health, Inc

875 Mahler Road, Ste. 168 Burlingame, CA, 94010 +1 415-890-3961 www.calahealth.com Job Description: Senior Data Engineer Cala Health, Inc. About Cala Health Cala Health is a bioelectronic medicine company transforming the standard of care for chronic disease. The company's wearable neuromodulation therapies merge innovations in neuroscience and technology to deliver individualized peripheral nerve stimulation. Cala Health’s lead product, Cala Trio™, is the only non-invasive prescription therapy for essential tremor and is now available through a unique digital business model of direct- to-patient solutions. New therapies are under development in neurology, cardiology, and psychiatry. The company is headquartered in the San Francisco Bay Area and backed by leading investors in both healthcare and technology. For more information, visit CalaHealth.com. The Opportunity We are looking for a Senior Data Engineer to expedite our Data Platform Stack to support our growth and also enable new product development in a dynamic, fast-paced startup environment. Specific Responsibilities also include ● Key stakeholder in influencing the roadmap of Cala’s Digital Therapeutics Data Platform. ● Build, operate and maintain highly scalable and reliable data pipelines to enable data collection from Cala wearables, partner systems, EMR systems and 3rd party clinical sources. ● Enable analysis and generation of insights from structured and unstructured data. ● Build Datawarehouse solutions that provide end-to-end management and traceability of patient longitudinal data, enable and optimize internal processes and product features. ● Implement processes and systems to monitor data quality, ensuring production data is always accurate and available for key stakeholders and business processes that depend on it. -

Software Assurance

Information Assurance State-of-the-Art Report Technology Analysis Center (IATAC) SOAR (SOAR) July 31, 2007 Data and Analysis Center for Software (DACS) Joint endeavor by IATAC with DACS Software Security Assurance Distribution Statement A E X C E E C L I L V E R N E Approved for public release; C S E I N N I IO DoD Data & Analysis Center for Software NF OR MAT distribution is unlimited. Information Assurance Technology Analysis Center (IATAC) Data and Analysis Center for Software (DACS) Joint endeavor by IATAC with DACS Software Security Assurance State-of-the-Art Report (SOAR) July 31, 2007 IATAC Authors: Karen Mercedes Goertzel Theodore Winograd Holly Lynne McKinley Lyndon Oh Michael Colon DACS Authors: Thomas McGibbon Elaine Fedchak Robert Vienneau Coordinating Editor: Karen Mercedes Goertzel Copy Editors: Margo Goldman Linda Billard Carolyn Quinn Creative Directors: Christina P. McNemar K. Ahnie Jenkins Art Director, Cover, and Book Design: Don Rowe Production: Brad Whitford Illustrations: Dustin Hurt Brad Whitford About the Authors Karen Mercedes Goertzel Information Assurance Technology Analysis Center (IATAC) Karen Mercedes Goertzel is a subject matter expert in software security assurance and information assurance, particularly multilevel secure systems and cross-domain information sharing. She supports the Department of Homeland Security Software Assurance Program and the National Security Agency’s Center for Assured Software, and was lead technologist for 3 years on the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) Application Security Program. Ms. Goertzel is currently lead author of a report on the state-of-the-art in software security assurance, and has also led in the creation of state-of-the-art reports for the Department of Defense (DoD) on information assurance and computer network defense technologies and research. -

Medical Devices

FRAUNHOFER INSTITUTE FOR EXPERIMENTAL SOFTWARE ENGINEERING IESE MEDICAL DEVICES Contact Fraunhofer Institute for Experimental Software Engineering IESE Ralf Kalmar Software is a part of our lives. Embedded into everyday equipment, into living and working en- [email protected] vironments or modern means of transportation, countless processors and controllers make our Phone: +49 631 6800-1603 lives simpler, safer, and more pleasant. We help organizations to develop software systems that www.iese.fraunhofer.de are dependable in every aspect, and empirically validate the necessary processes, methods, and techniques, emphasizing engineering-style principles such as measurability and transparency. Fraunhofer Institute for The Fraunhofer Institute for Experimental Software Engineering IESE in Kaiserslautern has been Experimental Software one of the world’s leading research institutes in the area of software and systems engineering Engineering IESE for more than 20 years. Its researchers have contributed their expertise in the areas of Process- es, Architecture, Security, Safety, Requirements Engineering, and User Experience in more than Fraunhofer-Platz 1 1,200 projects. 67663 Kaiserslautern Germany Under the leadership of Prof. Peter Liggesmeyer, Fraunhofer IESE is working on innovative topics related to digital ecosystems, such as Industrie 4.0, Big Data, and Cyber-Security. As a technology and innovation partner for the digital transformation in the areas of Autonomous & Cyber-Physical Systems and Digital Services, the institute’s research focuses on the interaction between embedded systems and information systems in digital ecosystems. Fraunhofer IESE is one of 72 institutes and research units of the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. To- gether they have a major impact on shaping applied research in Europe and contribute to Ger- many’s competitiveness in international markets. -

ECSO State of the Art Syllabus V1 ABOUT ECSO

STATE OF THE ART SYLLABUS Overview of existing Cybersecurity standards and certification schemes WG1 I Standardisation, certification, labelling and supply chain management JUNE 2017 ECSO State of the Art Syllabus v1 ABOUT ECSO The European Cyber Security Organisation (ECSO) ASBL is a fully self-financed non-for-profit organisation under the Belgian law, established in June 2016. ECSO represents the contractual counterpart to the European Commission for the implementation of the Cyber Security contractual Public-Private Partnership (cPPP). ECSO members include a wide variety of stakeholders across EU Member States, EEA / EFTA Countries and H2020 associated countries, such as large companies, SMEs and Start-ups, research centres, universities, end-users, operators, clusters and association as well as European Member State’s local, regional and national administrations. More information about ECSO and its work can be found at www.ecs-org.eu. Contact For queries in relation to this document, please use [email protected]. For media enquiries about this document, please use [email protected]. Disclaimer The document was intended for reference purposes by ECSO WG1 and was allowed to be distributed outside ECSO. Despite the authors’ best efforts, no guarantee is given that the information in this document is complete and accurate. Readers of this document are encouraged to send any missing information or corrections to the ECSO WG1, please use [email protected]. This document integrates the contributions received from ECSO members until April 2017. Cybersecurity is a very dynamic field. As a result, standards and schemes for assessing Cybersecurity are being developed and updated frequently. -

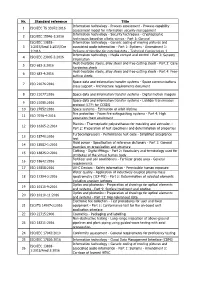

Nr. Standard Reference Title 1 ISO/IEC TS 33072:2016 Information Technology

Nr. Standard reference Title Information technology - Process assessment - Process capability 1 ISO/IEC TS 33072:2016 assessment model for information security management Information technology - Security techniques - Cryptographic 2 ISO/IEC 15946-1:2016 techniques based on elliptic curves - Part 1: General ISO/IEC 13818- Information technology - Generic coding of moving pictures and 3 1:2015/Amd 1:2015/Cor associated audio information - Part 1: Systems - Amendment 1: 1:2016 Delivery of timeline for external data - Technical Corrigendum 1 Information technology - Media context and control - Part 3: Sensory 4 ISO/IEC 23005-3:2016 information Heat-treatable steels, alloy steels and free-cutting steels - Part 3: Case- 5 ISO 683-3:2016 hardening steels Heat-treatable steels, alloy steels and free-cutting steels - Part 4: Free- 6 ISO 683-4:2016 cutting steels Space data and information transfer systems - Space communications 7 ISO 21076:2016 cross support - Architecture requirements document 8 ISO 21077:2016 Space data and information transfer systems - Digital motion imagery Space data and information transfer systems - Licklider transmission 9 ISO 21080:2016 protocol (LTP) for CCSDS 10 ISO 27852:2016 Space systems - Estimation of orbit lifetime Fire protection - Foam fire extinguishing systems - Part 4: High 11 ISO 7076-4:2016 expansion foam equipment Plastics - Thermoplastic polyurethanes for moulding and extrusion - 12 ISO 16365-2:2014 Part 2: Preparation of test specimens and determination of properties Turbocompressors - Performance test -

Mdcg 2019-16

Medical Device Medical Device Coordination Group Document MDCG 2019-16 MDCG 2019-16 Guidance on Cybersecurity for medical devices December 2019 This document has been endorsed by the Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) established by Article 103 of Regulation (EU) 2017/745. The MDCG is composed of representatives of all Member States and it is chaired by a representative of the European Commission.The document is not a European Commission document and it cannot be regarded as reflecting the official position of the European Commission. Any views expressed in this document are not legally binding and only the Court of Justice of the European Union can give binding interpretations of Union law. Page 1 of 46 Medical Device Medical Device Coordination Group Document MDCG 2019-16 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2. Objectives ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.3. Cybersecurity Requirements included in Annex I of the Medical Devices Regulations ........ 4 1.4. Other Cybersecurity Requirements ......................................................................................... 6 1.5. Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... -

BSI Medical Devices: Webinar Q&A

ISO 14971:2019 Risk Management for Medical Devices: Webinar Q&A November 2019 BSI Medical Devices: Webinar Q&A ISO 14971:2019 Risk Management for Medical Devices 13 November 2019 Page 1 of 10 ISO 14971:2019 Risk Management for Medical Devices: Webinar Q&A November 2019 Q&A Q. Should EN ISO 14971:2012 be used to demonstrate continued compliance to the ERs or GSPRs or use the 2019 revision of the standard? A. A manufacturer must demonstrate compliance to the applicable legislation. Harmonization of a standard allows for a presumption of conformity to the applicable legislation where the standard is applied and the manufacturer considers the Qualifying remarks/Notes in Annex Z. Additional clarification has been made available from the European Commission, whereby it is now considered that the recent editions of standards published by standardizers reflect the state of the art, regardless of its referencing in the OJEU and therefore the ISO 14971:2019 version represents the state of the art for the Medical Device Directives and Regulation. This update is welcomed as it provides clarity for industry and ensures manufacturers need only to comply with a single version of a standard. It is anticipated the 2019 revision will be harmonized to the Regulations. Q. From the Date of Application of the MDR and IVDR will the technical documentation for existing Directive certificates be required to be updated to the 2019 revision of the standard, considering the transitional provisions of MDR Article 120 and IVDR Article 110? A. A manufacturer must demonstrate compliance to the applicable legislation. -

Thesis and Dissertation Template

DEVELOPMENT OF A QUALITY MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT TOOL TO EVALUATE SOFTWARE USING SOFTWARE QUALITY MANAGEMENT BEST PRACTICES Item Type Other Authors Erukulapati, Kishore Publisher Cunningham Memorial library, Terre Haute,Indiana State University Download date 23/09/2021 23:31:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12347 DEVELOPMENT OF A QUALITY MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT TOOL TO EVALUATE SOFTWARE USING SOFTWARE QUALITY MANAGEMENT BEST PRACTICES _______________________ A Dissertation Presented to The College of Graduate and Professional Studies College of Technology Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _______________________ by Kishore Erukulapati December 2017 © Kishore Erukulapati 2017 Keywords: Software Quality, Technology Management, Software Quality Management, Bibliometric techniques, Best Practices VITA Kishore Erukulapati EDUCATION Ph.D. Indiana State University (ISU), Terre Haute, IN. Technology Management, 2017. M.S. California State University (CSU), Dominguez Hills, CA. Quality Assurance, 2011. B.Tech. National Institute of Technology (NIT), Calicut, Kerala, India. Computer Science and Engineering, 1996. INDUSTRIAL EXPERIENCE 2011-Present Hawaii Medical Service Association. Position: Senior IT Consultant. 2008-2010 Telvent. Position: Operations Manager. 2008-2008 ACG Tech Systems. Position: Test Manager. 2000-2008 IBM Global Services. Position: Project Manager. 1996-2000 Tata Consultancy Services. Position: System Analyst. PUBLICATIONS/PRESENTATIONS Erukulapati, K., & Sinn, J. W. (2017). Better Intelligence. Quality Progress, 50 (9), 34-40. Erukulapati, K. (2016). What Can Software Quality Engineering Contribute to Cybersecurity?. Software Quality Professional, 19(1). Erukulapati, K. (2015, Dec 2). Information Technology in Healthcare: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Presented at IEEE Hawaii Chapter - Computer Society Meeting, Honolulu, Hawaii. -

A Reference Architecture for Secure Medical Devices Steven Harp, Todd Carpenter, and John Hatcliff

FEATURE © Copyright AAMI 2018. Single user license only. Copying, networking, and distribution prohibited. A Reference Architecture for Secure Medical Devices Steven Harp, Todd Carpenter, and John Hatcliff Abstract and users cannot assume that medical Steven Harp, is a distinguished We propose a reference architecture aimed at devices will operate in a benign security engineer at Adventium Labs in supporting the safety and security of medical environment. Any device that is capable of Minneapolis, MN. Email: steven. devices. The ISOSCELES (Intrinsically connecting to a network or physically [email protected] Secure, Open, and Safe Cyber-Physically exposes any sort of data port is potentially at Enabled, Life-Critical Essential Services) risk. How should we think about and Todd Carpenter, is chief engineer architecture is justified by a collection of design manage risk in this context? at Adventium Labs in Minneapolis, principles that leverage recent advances in This question has been explored exten- MN. Email: todd.carpenter@ software component isolation based on sively.3,4 Special publications from the adventiumlabs.com hypervisor and other separation technologies. National Institute of Standards and Technol- The instantiation of the architecture for ogy (e.g., 800-39) provide a conceptual risk John Hatcliff, PhD, is a particular medical devices is supported by a management framework.5,6 AAMI TIR577 distinguished professor at Kansas development process based on Architecture describes how security risk management State University in Manhattan, KS. Analysis and Design Language. The architec- can be integrated with safety risk manage- Email: [email protected] ture models support safety and security ment (e.g., as addressed in ISO 14971 and analysis as part of a broader risk management specifically for medical devices in IEC framework. -

Quality Factors for Mobile Medical Apps

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Proceedings of the Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems 229 Quality Factors for Mobile Medical Apps Nadica Hrgarek Lechner Vjeran Strahonja MED-EL Elektromedizinische Geräte GmbH Faculty of Organization and Informatics Fürstenweg 77, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria Pavlinska 2, 42000 Varaždin, Croatia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract. The increased use of mobile phones, less in healthcare. According to a report from the smartphones, tablets, and connected wearable devices business consulting firm Grand Review Research, Inc. has fostered the development of mobile medical (2016), the global connected health and wellness applications (apps) in the last few years. Mobile devices market is expected to reach USD 612.0 billion medical apps are developed to extend or replace some by 2024. existing applications that run on a desktop or laptop The results of the sixth annual study on mobile computer, or on a remote server. health app publishing done by research2guidance If mobile apps are used, for example, to diagnose, (2016) are based on 2,600 plus respondents who mitigate, treat, cure, or prevent human diseases, participated in the online survey. As displayed in Fig. patient safety is at potential risk if the apps do not 1, remote monitoring, diagnostic, and medical function as intended. Therefore, such apps need to be condition management apps are the top three mHealth cleared, approved, or otherwise regulated in order to app types offering the highest market potential in the protect public health. next five years. In 2016, 32% of total respondents There are many papers that have been published predicted remote monitoring apps as the app category about the quality attributes of mobile apps. -

Relevant Norms and Standards

Appendix A Relevant norms and standards A.1 A Short Overview of the Most Relevant Process Standards There is a huge number of different process standards, and Fig. A.1 contains an overview of the most relevant such standards as covered in this book, showing the topics covered. A more extensive list of the relevant standards will be provided in the following section below. ISO/IEC 15504, ISO 19011 ISO/IEC 330xx Auditing man- agement systems Process Process assessment ISO/IEC 20000-1 ISO 9001 ISO/IEC 15504-6 ISO/IEC 15504-5 Service management QM system re- System life cycle PAM Software life cycle PAM Assessments, audits Criteria system requirements quirements ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288 ISO/IEC/IEEE 12207 ITIL System life cy- Software life cy- IT Infrastruc- cle processes cle processes ture Library COBIT Life cycle processes SWEBoK Software engineering Funda- Body of Knowledge mentals ISO/IEC/IEEE 24765 ISO 9000 Systems and SW Engineering Vocabulary QM fundamentals (SEVOCAB) and vocabulary Vocabulary Systems Software Organzational IT Quality Management Engineering Engineering Fig. A.1 Overview of the most important standards for software processes © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 327 R. Kneuper, Software Processes and Life Cycle Models, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98845-0 328 A Relevant norms and standards A.2 ISO and IEC Standards The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is the main international standard-setting organisation, working with representatives from many national standard-setting organisations. Standards referring to electrical, electronic and re- lated technologies, including software, are often published jointly with its sister organisation, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), but IEC also publishes a number of standards on their own. -

Standards Action Layout SAV3645.Fp5

PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY THE AMERICAN NATIONAL STANDARDS INSTITUTE 25 West 43rd Street, NY, NY 10036 VOL. 36, #45 November 11, 2005 Contents American National Standards Call for Comment on Standards Proposals ................................................ 2 Call for Comment Contact Information ....................................................... 6 Initiation of Canvasses ................................................................................. 8 Final Actions.................................................................................................. 9 Project Initiation Notification System (PINS).............................................. 10 International Standards ISO Draft Standards ...................................................................................... 15 ISO Newly Published Standards .................................................................. 16 Proposed Foreign Government Regulations................................................ 18 Information Concerning ................................................................................. 19 Standards Action is now available via the World Wide Web For your convenience Standards Action can now be down- loaded from the following web address: http://www.ansi.org/news_publications/periodicals/standards _action/standards_action.aspx?menuid=7 American National Standards Call for comment on proposals listed This section solicits public comments on proposed draft new American National Standards, including the national adoption of Ordering Instructions