Loyalty in Revolutionary Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genealogical Sketch of the Descendants of Samuel Spencer Of

C)\\vA CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 096 785 351 Cornell University Library The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785351 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY : GENEALOGICAL SKETCH OF THE DESCENDANTS OF Samuel Spencer OF PENNSYLVANIA BY HOWARD M. JENKINS AUTHOR OF " HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS RELATING TO GWYNEDD," VOLUME ONE, "MEMORIAL HISTORY OF PHILADELPHIA," ETC., ETC. |)l)Uabei|it)ia FERRIS & LEACH 29 North Seventh Street 1904 . CONTENTS. Page I. Samuel Spencer, Immigrant, I 11. John Spencer, of Bucks County, II III. Samuel Spencer's Wife : The Whittons, H IV. Samuel Spencer, 2nd, 22 V. William. Spencer, of Bucks, 36 VI. The Spencer Genealogy 1 First and Second Generations, 2. Third Generation, J. Fourth Generation, 79 ^. Fifth Generation, 114. J. Sixth Generation, 175 6. Seventh Generation, . 225 VII. Supplementary .... 233 ' ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS. Page 32, third line, "adjourned" should be, of course, "adjoined." Page 33, footnote, the date 1877 should read 1787. " " Page 37, twelfth line from bottom, Three Tons should be "Three Tuns. ' Page 61, Hannah (Shoemaker) Shoemaker, Owen's second wife, must have been a grand-niece, not cousin, of Gaynor and Eliza. Thus : Joseph Lukens and Elizabeth Spencer. Hannah, m. Shoemaker. Gaynor Eliza Other children. I Charles Shoemaker Hannah, m. Owen S. Page 62, the name Horsham is divided at end of line as if pronounced Hor-sham ; the pronunciation is Hors-ham. -

Loyalists in War, Americans in Peace: the Reintegration of the Loyalists, 1775-1800

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 Aaron N. Coleman University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Coleman, Aaron N., "LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 620. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/620 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERATION Aaron N. Coleman The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aaron N. Coleman Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Daniel Blake Smith, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Aaron N. Coleman 2008 iv ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 After the American Revolution a number of Loyalists, those colonial Americans who remained loyal to England during the War for Independence, did not relocate to the other dominions of the British Empire. -

In but Not of the Revolution: Loyalty, Liberty, and the British Occupation of Philadelphia

IN BUT NOT OF THE REVOLUTION: LOYALTY, LIBERTY, AND THE BRITISH OCCUPATION OF PHILADELPHIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Aaron Sullivan May 2014 Examining Committee Members: David Waldstreicher, Advisory Chair, Department of History Susan Klepp, Department of History Gregory Urwin, Department of History Judith Van Buskirk, External Member, SUNY Cortland © Copyright 2014 by Aaron Sullivan All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT A significant number of Pennsylvanians were not, in any meaningful sense, either revolutionaries or loyalists during the American War for Independence. Rather, they were disaffected from both sides in the imperial dispute, preferring, when possible, to avoid engagement with the Revolution altogether. The British Occupation of Philadelphia in 1777 and 1778 laid bare the extent of this popular disengagement and disinterest, as well as the dire lengths to which the Patriots would go to maintain the appearance of popular unity. Driven by a republican ideology that relied on popular consent in order to legitimate their new governments, American Patriots grew increasingly hostile, intolerant, and coercive toward those who refused to express their support for independence. By eliminating the revolutionaries’ monopoly on military force in the region, the occupation triggered a crisis for the Patriots as they saw popular support evaporate. The result was a vicious cycle of increasing alienation as the revolutionaries embraced ever more brutal measures in attempts to secure the political acquiescence and material assistance of an increasingly disaffected population. The British withdrawal in 1778, by abandoning the region’s few true loyalists and leaving many convinced that American Independence was now inevitable, shattered what little loyalism remained in the region and left the revolutionaries secure in their control of the state. -

High Street, from Ninth Street, Philadelphia"

Lu Ann De Cunzo AN HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF WILLIAM BIRCH'S PRINT "HIGH STREET, FROM NINTH STREET, PHILADELPHIA" PHILADELPHIA printmaking reached its apogee in 1800 with the appearance of The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylva- nia, North America; as it appeared in the year 1800 consisting of 28 Plates Drawn and Engraved by W Birch and Son, Published by W. Birch: Springland Cot, near Neshaminy Bridge on the Bristol Road, Pennsylvania, December 31, 1800. In the centuries prior to the advent of modern mass communication, prints circulated widely. An art expres- sion with universal appeal, the print served the dual purpose of entertaining and informing people pictorially of the world around them.' Today such prints are also historical documents. Supplemented by written records, these graphic representations can increase our understanding of the buildings, people and neighborhoods depicted. In this study information gathered from numerous sources provide insights into Philadelphia life in 1800 as well as the Birch print's meaning. William Birch had arrived in Philadelphia in 1794, having appren- ticed with a goldsmith in London and subsequently decided on a career as a painter of miniatures in enamel.2 So impressed was he with the city, he set out to produce a pictorial album of the city and its life; his medium, naturally, the print. In an Introduction to the volume, Birch states his aim thus: The ground on which it [Philadelphia] stands, was, less than a century ago, in a state of wild nature; covered with wood and inhabited by Indians. It has in this short time been raised as it were by magic powers, to the eminence of an opulent city, famous for its trade and commerce, crowded in its port with vessels of its own 109 110 PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY production and visited by others from all parts of the world . -

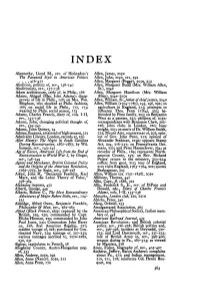

Abernethy, Lloyd M., Rev. of Hofstadter's the Paranoid Style In

INDEX Abernethy, Lloyd M., rev. of Hofstadter's Allen, James, 205/* The Paranoid Style in American Politics Allen, John, 20577, 221, 292 . , 416-417 Allen, Margaret (Peggy). 205?*, 212 Abolition, politics of, rev., 138-140 Allen, Margaret Budd (Mrs. William Allen, Abolitionists, rev., 137-138 Sr.), 20477 Adam architecture, style of, in Phila., 166 Allen, Margaret Hamilton (Mrs. William Adams, Abigail a (Mrs. John Adams): disap- Allen), 20477-20577 proves of life in Phila., 158; on Mrs. Wm. Allen, William, Sr., father of chief justice, 2047* Bingham, 160; shocked at Phila. fashions, Allen, William (1704-1780), 195, 196, 292; on 168; on social life in Phila., 172, 173; agriculture in England, 213; attempts to wearied by Phila. social season. 173 influence Thos. Penn (1764), 223^ be- Adams, Charles Francis, diary of, vols. I—II, friended by Penn family, 205; on Benjamin rev., 135-136 West as a painter, 221; children of, 205n; Adams, John, changing political thought of, correspondence with Benjamin Chew, 202- rev., 539-54O 226; joins clubs in London^ 220; loses Adams, John Quincy? 24 weight, 225; on merit of Dr. William Smith, Adams, Susanna, attainted of high treason, 312 225; Mount Airy, countryseat of, 202; opin- Admiralty Library, London, records at, 230 ion of Gov. John Penn, 212; opinion of Alexander Stedman, 21 gn; opposes Stamp After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina on During Reconstruction, 1861-1877, by Wil- Act, 204, 216-217; Pennsylvania Ger- liamson, rev., 143-145 mans, 222; and Peter Hasenclever, 224; as Age of Excess, American Life from the End of recorder of Phila., 189; represents North- Reconstruction to World War I, by Ginger, ampton County, 197; on Rev. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

LAUREL HILL NOW KNOWN AS THE RANDOLPH MANSION, EAST FAIRMOUNT PARK, PHILADELPHIA FRONT VIEW FACING EAST THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY. VOL. XXXV. 1911. No. 4 LAUREL HILL AND SOME COLONIAL DAMES WHO ONCE LIVED THERE. BY WILLIAM BROOKE RAWLE, ESQUIRE. A paper read May 1, 1901, before the Society of The Colonial Dames of America, Chapter II, Philadelphia, upon the opening of the Randolph Mansion (as it is now called) in East Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, by that organization, in whose care and custody it had been placed by the Park Commissioners for restoration and occupancy.1 Members of the Society of The Colonial Dames of America, Ladies and Gentlemen:— It is a common custom in these United States of ours to treat as almost antediluvian the events which occurred before the American Revolution. The result of that glorious struggle for liberty and the rights of man was 1 Some of the following matter appears also in the account of "Laurel Hill and the Rawle Family," in the Second Volume of "Some Colonial Mansions and Those who Lived in Them," edited by Mr. Thomas Allen Glenn. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War Mr. Glenn entered the Military Service, leaving the article unfinished, and Mr. Henry T. Coates, the publisher of the book, requested me to finish it, which I did. I have not had any hesitancy, therefore, in repeating to some extent in this paper what I myself wrote for the work mentioned.—W. B. R. VOL. xxxv—25 (385) 386 Laurel Hill certainly a deluge—political and social. -

The Shoemaker Family

A Genealogical and Biographical Record OF THE SHOEMAKER FAMILY OF Gloucester and Salem Counties, N. J. 1765-1935 ♦ Traud and AsumDird by HUBERT BASTIAN SHOEMAKER OF PHILADELPHIA, PA. THE SHOEMAKER COAT OF ARMS The coat of arms displayed on the opposite page is taken from "Matthews American Armoury and Blue Book," where are recorded coats of arms of numerous faou1ies, origin and authenticity not always traced. It might be relevant t::. state for the benefit of those not conversant with heraldry that i,, ..ncient times the armor of metal worn by those in combat as a protection consisted of a shield or breast plate, a helmet etc., and the shield especially, as painted became characteristic of the individual bearers. And so it arose as a family insignia or distinction and descended to modern times and is used now in various ways on plate, jewelry, motor cars or in genealogies, or printed for framing, etc. The coat of arms in the first place may have been usurped by a particular family or secondly granted by regal authority and thence handed down and ·considered as belonging to all descendants of the blood. The Shoemaker coat of arms is represented by a shield of sable which is a tincture of black represented by criss-cross perpendicular and horizontal lines. Within this shield are three chevronels. A chevron is a house rafter and chevronel its diminutive as worn on the sleeves of officers. These chevronels are shown in ermine, a white field with black dots. Above the helmet covering the head is the crest. -

Rawle Family Papers, 1682-1921 (Bulk 1770-1911) 14 Boxes, 37 Vols., 10 Lin

Rawle Family Papers, 1682-1921 (bulk 1770-1911) 14 boxes, 37 vols., 10 lin. feet Collection 536 Abstract The Rawle family, which produced some of the leading legal minds in early Pennsylvania history, first immigrated to America in 1686 to escape the persecution their Quaker faith invited in England. From his arrival in Pennsylvania, Francis Rawle Jr. (1663-1727) became involved in the religious and legal life of the colony, a position bolstered by his marriage to Robert Turner’s daughter Martha in 1689. Francis’s grandson William (1759-1836) was the first Rawle to rise to prominence in the legal profession, serving as Pennsylvania’s first U.S. attorney and founding a prestigious law office, now known as Rawle and Henderson and recognized as the country’s oldest practice. Rawle was followed in his legal career by a number of subsequent generations of Rawle men, most of whom were also named William. This list includes William Rawle Jr. (1788-1858), his son William Henry Rawle (1823-1889), and William Rawle Brooke (1843-1915), known for most of his life as William Brooke Rawle. In addition to their legal activities, the Rawles served as founding and/or contributing members of a number of Philadelphia institutions, including the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the American Philosophical Society, the University of Pennsylvania, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. This collection contains legal documents related to the firm of William Rawle and his descendants, personal and professional correspondence, and a substantial amount of genealogical material. The personal material is mostly found in the correspondence of William Rawle Sr., William Rawle Jr., William Brooke Rawle, and Rebecca Rawle Shoemaker, as well as journals kept by William Rawle Sr. -

The Loyalists of Pennsylvania

The Ohio State University Bulletin VOLUME XXIV APRIL 1, 1920 NUMBER 23 CONTRIBUTIONS IN HISTORY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE NUMBER 5 The Loyalists of Pennsylvania BY WILBUR H. SIEBERT Professor in The Ohio State University PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY AT COLUMBUS Entered as second-class matter November 17, 1905, at the post-office at Columbus, Ohio, under Act of Congress, July 16, 1894. r\ CONTENTS CHAPTER I THE LOYALISTS ON THE UPPER OHIO PAGE Dunmore, Connolly, and Loyalism at Fort Pitt 9 Connolly s Plot 10 The Loyalists Plan to Capture Red Stone Old Fort 13 Flight of the Loyalist Leaders from Pittsburgh, March 28, 1778 14 Loyalist Associations and the Plot of 1779-1781 15 Where the Refugees from the Upper Ohio Settled after the War 17 CHAPTER II THE LOYALISTS OF NORTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA The Loyalists on the Upper Delaware and Upper Susquehanna Rivers ... 19 Exodus of Loyalists from the Susquehanna to Fort Niagara, 1777-1778 19 The Escort of Tory Parties from the Upper Valleys to Niagara 20 Where These Loyalists Settled 21 CHAPTER III THE REPRESSION OF LOYALISTS AND NEUTRALS IN SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA Political Sentiment in Philadelphia and Its Neighborhood in 1775 22 Operations of the Committee of Safety, 1775-1776 23 Activities of the Committee of Bucks County, July 21, 1775, to August 12, 1776 26 Effect of the Election of April, 1776, in Philadelphia 27 Tory Clubs in the City 27 The Constitutional Convention of Pennsylvania, July, 1776, and Later.. 28 Effect of Howe s Invasion of New Jersey, November and December, 1776 29 Continued Disaffection -

"Loyalist Problem" in the Early Republic: Naturalization, Navigation and the Cultural Solution, 1783--1850 Emily Iggulden University of New Hampshire, Durham

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNH Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2008 The "Loyalist problem" in the early republic: Naturalization, navigation and the cultural solution, 1783--1850 Emily Iggulden University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Iggulden, Emily, "The "Loyalist problem" in the early republic: Naturalization, navigation and the cultural solution, 1783--1850" (2008). Master's Theses and Capstones. 89. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/89 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE "LOYALIST PROBLEM" IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC: NATURALIZATION, NAVIGATION AND THE CULTURAL SOLUTION, 1783-1850. BY EMILY IGGULDEN BA History, University of Glasgow, 2005 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2008 UMI Number: 1459498 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Park Houses F AIRMOUNT from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Visit Fairmountparkhouses.Org Or the Museum’S PARK HOUSES Visitor Services Desks

Philadelphia’s acquisition of the historic houses, beginning with Lemon Hill: West Sedgley Drive and Poplar Drive (19130) Within Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park stands a group Lemon Hill in 1844, resulted in the creation of Fairmount Mount Pleasant: 3800 Mount Pleasant Drive (19121) of seven eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century historic houses Park, one of the largest municipal parks in the country. This Laurel Hill: Randolph Drive and East Edgely Drive (19121) established as rural retreats by prominent families of the city. led to the preservation of the houses, the most significant Woodford: 33rd Street and West Dauphin Street (19132) Some of these homes functioned as working farms, including group of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century domestic Strawberry Mansion: 2450 Strawberry Mansion Drive (19132) productive dairies, orchards, and extensive fields and game lands, architectural examples in the United States. Illustrating more while others provided an elegant, fashionable, and healthy Cedar Grove: Lansdowne Drive and Cedar Grove Drive (19131) than a century of style, fashion, and domestic life, the houses summer retreat from Philadelphia’s urban environment, heat, provide a unique glimpse into Philadelphia’s rich history. Sweetbriar: 3800 Sweetbriar Drive (19131) and periodic epidemics. For directions to the Fairmount Park Houses F AIRMOUNT from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, visit fairmountparkhouses.org or the Museum’s PARK HOUSES Visitor Services Desks. Philadelphia’s Historic Villas along the Schuylkill River WEST FAIRMOUNT -

I[,F)Cncalogical 1 ''{J

i----------------------------j \ I I Ii \! 1\~.-rotbs1 ''{j " , .I i[,f)cncalogical I I I I If I ! ' \ Relating to the families of l t I i ; l t I I connected dil'ectly OI' l'emotety with them FROM THE ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT OF JAMES P. PARKE" AND TOWNSEND WARD, WITH NOTES, ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS EDITED AT THE REQUEST OF CfIARLES HARE I-IUTCHINSON MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND GENEA LOGICAL SOCIETIES OF PENNSYLVANIA BY THOMAS A.LLEN GLENN Printed for private distribution PHILADELPHIA MDCCCXCVIII ! L_._,;......,,.,. •• -- GENEALOGICAL NOTES RELATING TO THE FAMILIES OF Lloyd, Pemberton, Hutchinson, Hudson and Parke. PREFACE. THE following genealogical notes, relating chiefly to the families of Lloyd, Pemberton, Hutchinson, Hudson and Parke were first compiled, in July, 1849, by James P. Parke, and copied and added to, in 1877, by Townsend Ward, now deceased, then Librarian of the Historical Society of Penn sylvania. The sources of genealogical information at that time open to the student of family history, as compared with the present day, were insignificant, and it is a matter of surprise that with such scant material at hand so valu able a record was made. Mr. Ward states in his preface that the information regarding the Lloyd family was "mostly from a document sent by Francis Lloyd of Bjrmingham [England], on Sep tember 29, 1826, to Joseph P. Norris, of Philadelphia, and which it is said was compiled from authentic records by Charles Lloyd the second [ of Dolobran], dated 1670." The other data were gathered in much the same way, by laborious research, from family archives.